Traditional Jewish Separatism and De-humanization of Gentiles: A Review of Stephen Bloom’s Postville

[W]hat the Postville Hasidim ultimately offered me was a glimpse at the dark side of my own faith, a look at Jewish extremists whose behavior not only made the Postville locals wince, but made me wince.

Stephen Bloom

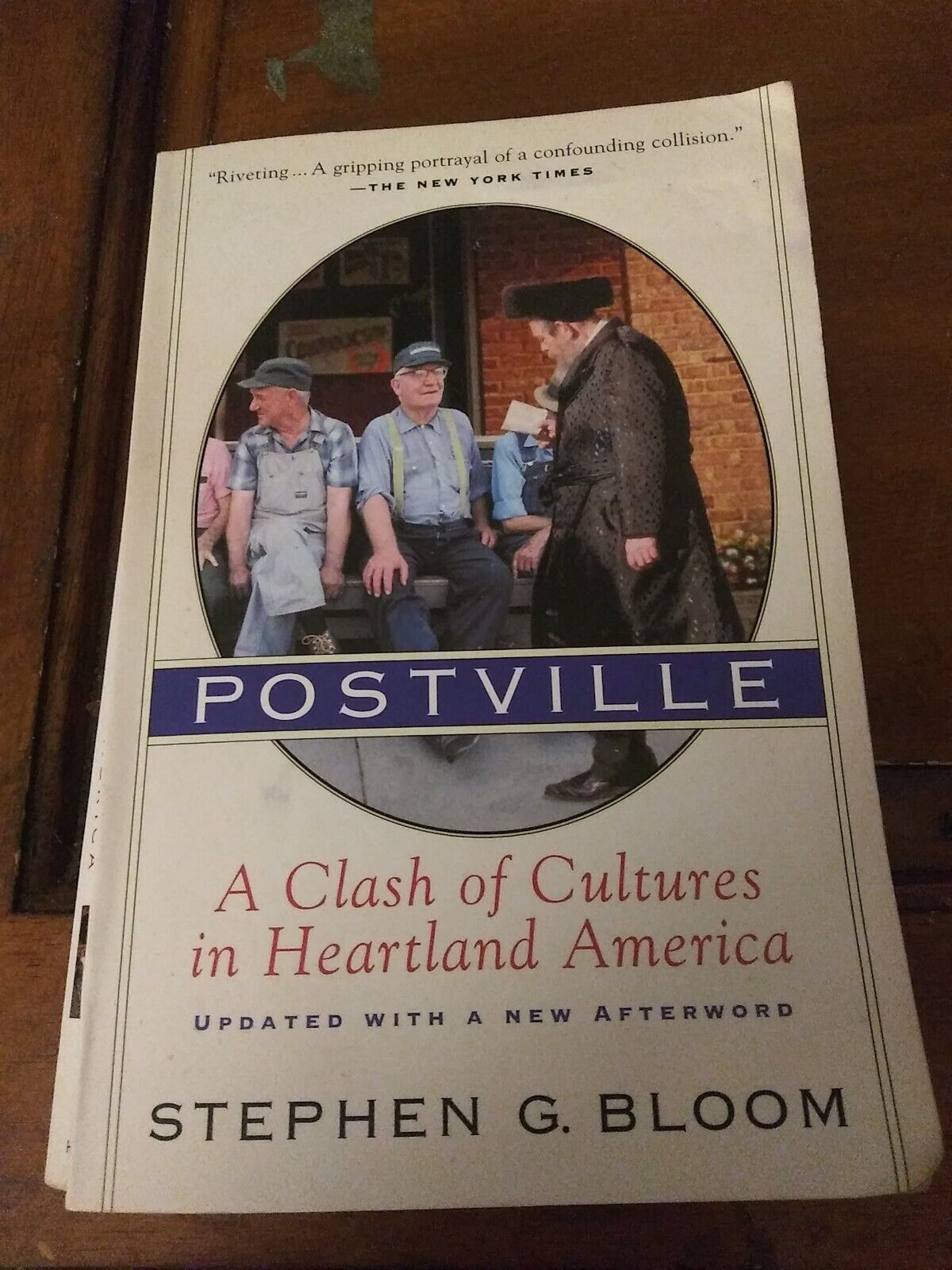

Postville: A Clash of Cultures in Heartland America

Stephen G. Bloom

Mariner Books, 2001 (originally published by Harcourt in 2000)

7367 words

* * *

Did Stephen Bloom write a book that savaged the Jews?

More than twenty years ago, a journalism professor from the University of Iowa, Stephen Bloom, published a highly readable and fascinating book on an incredible culture clash that played out in the Northeastern Iowa town of Postville; a description of the difficulty that the transplantation of a Hasidic Jewish community into a withering, rural Iowa farm town in the 1980s and 1990s posed from both the Jewish and native Iowan perspective alike. The author’s Jewishness, fairly or unfairly, allowed him access to the Hasidic community that no gentile would have been afforded; the author’s secularism and “local” status allowed him access to the native Iowan community as well. What follows then is a sketch of two antagonistic communities from the inside out.

Bloom is a talented writer — he weaves scenes and characters that are compelling. In many ways, Postville reads like a novel in the sense that the characters he introduces and develops become fixtures in the mind of the reader — we know them and are interested in them. While I am not sure that Postville teaches us something we did not already know — it is an intriguing look at the Hasidic movement and the death of rural America, all at the same time. And while Bloom showed an implied hostility against a strongly manifested faith — and that bias is palpable throughout the book — his irreligiosity was not so overwhelming to distract from the overall evenhandedness of the book.

If anything, the years that have passed have made the book more relevant than even when it was published. It is the intersection, and future, of religion in America and America itself — as it was, as it is, and as it is becoming. Not only is the story of Postville one of rural and urban, immigrant and native, and Christian and Jewish, but it is also the account of Jewish versus Jewish — the Jewishness of intense insularity versus the Jewishness of liberal cosmopolitanism, the Jewishness of tribalism versus the Jewishness of universalism. Bloom’s book about the culture clash between Hasidic Jews and rural Iowans is riveting on many levels but one that figures most prominently is the theme of Jewish inward-looking supremacism, and how this theme correlates with Jewish religiosity. Simply stated, the more religious a Jew is, the more he believes that he must turn within the Jewish community and shun the gentile (lest he, the religious Jew, is contaminated by the filth and impurity of the gentile). Not only does he not love the gentile in any conceivable way, but the religious Jew is categorically indifferent to the gentile’s existence as if the gentile does not matter in any essential way—that the gentile has no moral worth. There is then a powerful and undeniable correlation between Jewish religious intensity and observance and insularity from, and indifference to, the “other.” Of course, as I have known from experience, not every religious Jew is hostile and indifferent to gentiles per se. But the gravity exerted within religious Judaism is one that pulls towards itself — fundamentally, religious Judaism is not interested in the world outside of its narrow parameters. By contrast, the more religious a Christian becomes, the more he loves (or should love) all men as his neighbor — Christianity as a creed cannot produce anything approaching Jewish supremacism and insularity because Christianity is uniquely universal. For the Christian, Jew and gentile are essentially equal in dignity before God — for the religious Jew, such a concept would be totally unacceptable. And, as an “ultra” orthodox outpost, Postville recounts appalling episodes of indifference and hostility towards the gentiles by the Postville Jews.

All of it plays out — this brutal culture clash — through the filter and musings of a Jewish author who embodies and personifies the insecurity of the “emancipated” Jew who is home in no place. Because secular Jews have become synonymous, to one extent or another, with modern liberalism and at least the appeal of universal values, the idea of Jewish supremacism that undergirds the Hasidic Jewish religiosity is something that is, to say the very least, an uncomfortable reality. But unlike the secular Jew’s visceral reaction and discomfort with displays of religious fervor by Christians, secular Jews have a more muted and compromised response to intensely religious Judaism. There is something much more forgiving in the secular Jew’s consideration of their religious cousins — a lack of harshness — that distinguishes intra-Jewish relationships. By contrast, apostate or secular Christians are almost universally nasty and unforgiving towards their religious cousins. And, to some extent, that distinction makes sense; Judaism is primarily an ethnicity that has credal aspects while Christianity is primarily a creed with ethnic aspects — as such, disputes about beliefs are often forgiven by “family” members but not by people who are defined by faith and adherence. Bloom, as a secular American liberal and Jew, turns out to be an exception to the rule — a Jew who nonetheless takes his “Americanism” and “liberalism” seriously enough to turn his caustic pen on religious Jews. And he learned this hostility in real time while writing Postville. His book then is more than the account of a kulturkampf that played out in rural Iowa; it was a conscious discovery of the ugliness of Jewish chauvinism in its most religious form.

* * *

Working professionally as I do with many Jews who keep Kosher means that I have dined in many Kosher restaurants. Kosher food can be good, and some of the restaurants are excellent. They are also expensive: Kosher food is significantly costlier than non-Kosher food. Kosher food is more than merely Jewishly blessed food — it is a particular method of slaughter, storage, and preparation — and blessing. Kosher meat cannot be sourced from a gentile butcher because the animal must be slaughtered and drained of blood in a precise manner. Obviously then, religious Jews require ready access to meat that is slaughtered and prepared in accordance with religious law. As religious Jews have flourished in the United States — gaining numbers from fecundity and converts from mainstream Judaism, while Reform and Conservative Judaism have floundered — the need to Kosher food has only increased. Thus an underlying theme to Postville is the sizable business opportunity to feed the growing need for Kosher meat throughout the United States and abroad. Postville is eponymously centered in Postville, Iowa — where a group of investors from the Orthodox Lubavitch Jewish community in Crown Heights, New York purchased an abandoned slaughterhouse and turned it into a large Kosher butchery in 1987. In a sense then, Postville is first a story of the seizure of an economic opportunity that is, as such, uniquely an American story. The investors were led by a Russian-born Lubavitcher named Aaron Rubashkin, and Rubashkin led a migration of families to Postville to manage the Kosher slaughterhouse.

Initially, the Postville residents and civic leaders welcomed the investment in their community and the economic impact it would bring. Postville was reeling in the mid-1980s. The United States experienced a major agricultural crisis during the 1980s. Record production during this time led to a plunge in the price of commodities. Exports fell, due in part to the 1980 United States grain embargo against the Soviet Union. Farm debt for land and equipment purchases soared during the 1970s and early 1980s, doubling between 1978 and 1984. Other negative economic factors included high interest rates, high oil prices and a strong dollar. By the mid-1980s, the crisis had reached its peak. Land prices fell dramatically, leading to record foreclosures. Some forty years later, it is hard to imagine a collapse in value of quality farmland, especially in a place as fertile as Iowa, but in the mid-1980s, rural America was decimated in a way that not merely destroyed countless family farms but scarred the American rural way of life forever.

The refurbishing of the abandoned slaughterhouse and the addition of several hundred people to the local economy indeed provided Postville a modest economic bump, but problems between the Hasidic Jews and Iowans began immediately afterwards and persisted for decades. And more than that, the meat-processing plant brought in hundreds of illegal immigrants as workers — thus operating to apply a double pressure of change to what had been a longstanding homogeneous community. The Iowans were expecting new neighbors who would acclimate to the Iowa way of hospitality and cooperation — who would add more than economic value to their community — but instead were matched with religious Jews who viewed those goyim as virtually sub-human and treated them accordingly with vacillations of indifference or hostility.

Bloom was a professor of journalism at the nearby University of Iowa when he came across a reference in the local news of a nearby Hasidic outpost — and accompanying tension — in Postville in the mid-1990s. Bloom was admittedly dealing with a culture clash of his own after relocating from San Francisco after a career as a journalist. While Bloom’s initial interest was the desire to connect with his Jewishness amid Iowa’s overwhelming Christian homogeneity, the deteriorating situation between the Jews and the locals was a news story in its own right — in addition to the sheer peculiarity of Hasidic Jews living in rural Iowa. By the time he arrived in the mid-1990s, tensions were at a breaking point. The Iowans had made their stand against the Jews by deciding to hold a referendum to allow the town of Postville to annex the land on which the kosher meat-processing plant stood. If Postville annexed the land, the Iowans would then be able to raise taxes and better control the Lubavitchers. The annexation issue was thus a vote essentially to shame the Jews in Postville by the native Iowans of the town.

Bloom, like any investigative reporter, interviewed countless locals and tried, initially in vain, to do the same with the Postville Hasidic Jews. On some level, at least by implication, Bloom wanted to believe that the locals were anti-Semitic and, indeed, he found some comments by them to be exactly that. Indeed, there is an arrogance in how Bloom related to the native Postville people — as if he reduced to mere country bumpkins all the gentileswho simply did not know how to relate to outsiders. Thus, Bloom begins his account by frankly describing his suppressed, but deep-seated, dislike of the Iowans. At the same time, he also wanted to connect with the Hasidic Jews for their side of the story, but also because he was, at least in a sense, lost himself. As a coastal and secular Jew, he felt more than out-of-place in Iowa — he resented their version of middle America, and, to the extent that he was attracted to it, he resented that too. But he interviewed a variety of Iowa locals that he grew to like — he identified with them in terms of their values. At the very least, he understood them.

Northeastern Iowa is — or was — German-Lutheran country. And the imprints of neatness, cleanliness and mannerliness were seemingly everywhere in these communities. As Bloom described it in the mid-1990s, it sounded like America in the 1920s or earlier. White, religious, neighborly, civic, and orderly. It was the kind of place with Memorial Day and July 4th parades with the 4H Club, Future Farmers of America, and Chamber of Commerce — where chain stores, and Walmart in particular, were resisted, and people did not lock their doors. It is exactly the type of place that would later become ground zero for two independent phenomena — the opioid crisis and MAGA. But in the mid-1990s, this was still a place where World War II and Korean War veterans congregated in coffee shops in John Deere hats and overalls, where the high school football game was an event that the whole town eagerly waited on, where homes and yards were manicured, where people prided themselves on their sense of belonging and where “city-slicker” was a term that meant something. Understated, honest, lawful and thrifty, the local Iowans were simply not prepared (but, then again, who is) for a group to descend upon them who were shrewd, discourteous, and disorderly.

One way to look at the differences, at the most basic level, is that Jews (and this is not merely the ultra-orthodox) look at rules as pliable, and, in any event, not always applicable to any individual Jew. In this same way that Jews look at bargaining (“to hondle” in Yiddish) as a sign of intelligence, they also take a flexible view with respect to following rules for the sake of rules. German ethnics could not be more different — not only are they rules-oriented, but they are also rules-worshipping. Simple things like observing traffic and zoning laws become flashpoints that are hard for outsiders to understand. In many ways, Bloom was won over by the Iowans in their culture war with the Jews — slowly and surely — because their complaints that the Jews should just follow the rules everyone has to follow resonated with him. He may have been a secular, coastal Jew, but he did not accept a job in Iowa for no reason — he wanted to escape from wherever he was even if he did not realize it or know why. In a sense, he wanted “Ozzie and Harriet” even if it came without pastrami or a good bagel. That he chose to live in Iowa says something more about him than he himself was able to articulate. He was more receptive to the locals’ complaints that the Jews were rude and unneighborly than he wanted to admit.

But that was later — he was still, midstream in the book, searching for something in his own religion. After considerable difficulty, he finally managed to interview Aaron Rubashkin’s son, Sholom, who managed the operation in Postville to discuss the relations with the locals. The Lubavitchers are unique among Jews in that they are religious and proselytizers, at least towards wayward Jews. In many ways, they are like first-century Christians who missioned, at least initially, to other Jews. They are aggressive in their ministry and believe heartily that they can convince any such Jew to join them. Rubashkin began immediately to work on Bloom accordingly — to save his Jewish soul. Part of that outreach involves matching the wayward Jew with a model Lubavitcher family for a Shabbat weekend. Bloom was receptive to this for several reasons — first, he wanted to see the Lubavitchers from the inside out, and second, he was genuinely curious about whether they had something to say to fix, as it were, his longing for something more meaningful in his Jewish life.

Bloom’s weekend with the Lubavitcher was gracious enough. He, along with his young son, took part in every aspect of the worship and dining. He observed a Jewish life that was so far removed from his own that he felt a great divide between himself and the patriarch of that family, Lazar. The model Lubavitcher made any number of comments that chafed at him excessively — from the casual dismissal of every other type of Jewishness as something obviously inferior, to the gross characterizations of gentiles, from the outright racism to the nasty prejudice. He was embarrassed by the willingness to treat the goyim with such disrespect — to view them as worthless. In what would be a theme that runs throughout the book, the Lubavitchers thought about the locals as people to be avoided, to navigate among them, or take advantage of them — but, in any event, never people with whom they would fraternize. If there was friction, and there was, it was universally and categorically chalked up to anti-Semitism.

There was a palpable groupthink among the Jews that refused to see the perspective of the locals, let alone empathize with them. The Jews were strictly transactional with the locals — we live here, you live here, leave us alone. But it was more than mere avoidance for the sake of toleration — it was an almost glee in deceiving the goyim that irked Bloom. The locals were essentially non-entities to the Jews — lacking any inherent value as human beings. To the Jews, however, their theology towards the gentiles made perfect sense — the Jew alone possessed a special relationship with God that required an insularity to protect it. The outside world — the non-observant world — was marked by one overriding theme: contamination and filth. The idea of fraternizing with the locals — of making nice with them — was then, at least to the ultra-orthodox mind, something incomprehensible. By analogy, it would be like asking them to put themselves in the “near-occasion” of sin. The Lubavitchers could never understand why Bloom cared what the locals thought — one way or the other — when he, Bloom, stood at the precipice of entering the fullness of Jewish life which he was gifted with entering by virtue of his birth as a Jew.

Bloom’s foray into religious Jewish life is something, however, that began to grate on him — a lot. Whether he was ever open-minded about it or not, he could not shake off his internal compass of liberalism in assessing the Lubavitcher way of life. In what was an interesting twist in the book, Bloom’s sympathy for the religious Jews did not merely stop as he came face-to-face with Jewish indifference and rudeness to the locals — but when he came to see the exclusionary nature of the religion from the inside out. In a sense, he became like an apostate (even though he was never a believer in that sense) in terms of his disgust with the Lubavitchers. They saw themselves as the best of Jews — he saw them as bigots and pious frauds. During his investigation, Bloom in fact confirmed that the Jews were very offensive to Postville’s civic leaders and the local populace. They often swindled contractors, retailers, and handymen by spreading out their payments over many months — when they did not simply toss the bill, that is. They drove too fast on the roads or simply ignored the parking rules. They drove jalopies with missing mufflers, and they parked them on their front laws. He recounts that one Jewish woman tried to bribe a policeman, and one Rabbi stole some handmade leather sheaths from a retailer, insisting that he had already paid for them. And they made the yards surrounding their homes into shambles — something which may seem insignificant on the surface, but which is nevertheless a sign of disrespect for the Germanic Iowans who took an inordinate pride in well-kept yards and homes as signs of civilization and breeding.

Another issue involved Postville’s municipal swimming pool. The Iowans were alarmed, legitimately at it turned out, that the Hasidic Jews would demand “Jews only” hours. Iowans would thus be displaced from a facility which they had built. As it turned out, the Lubavitchers eventually got their gentile-free time. There were also a great many zoning and building use violations. The Jews simply ignored the zoning rules as if they did not apply to them and built whatever they wanted wherever they wanted. About this, Bloom writes:

If the city of Postville tried to enforce any ordinance the Jews disagreed with, the immediate cry was anti-Semitism. If a local complained about the noise from the shul, if anyone disagreed about annexation, he or she was quickly branded an anti-Semite. Ultimately, I discovered, carrying on a conversation with any of the Postville Hasidim was virtually impossible. If you didn’t agree, you were at fault, part of the problem. You were paving the way for the ultimate destruction of the Jews, the world’s Chosen People. There was no room for compromise, no room for negotiation, no room for anything but total and complete submission.

Bloom’s attitudes grew more hostile to the Lubavitchers — so much so that he inserted himself into the story as someone actively rooted for the annexation vote to win and stick it to the Jews. Beyond the insolence and the refusal to treat the local goyim with even a modicum of respect, Bloom was vexed by the Jewish supremacism that he found among them during their attempts to proselytize him. The Lubavitchers also sensed that Bloom was a lost cause — an irredeemable Jew who did not — and would not — “get” it. Slowly but surely, Bloom became simply one of the non-Jews to the Lubavitchers.

Bloom was probably pushed to his limit when he researched a crime that involved a few dubious Lubavitchers that had happened years earlier. What he found disgusted him on several levels. He describes the September 27, 1991, crime spree of Lubavitchers Pinchas Lew and Phillip Stillman. The pair got drunk, removed the license plate from their car, and robbed two townspeople at gunpoint. They shot one woman — she recovered but the bullet was permanently lodged in her spine, causing her continual pain for the rest of her life. Bloom found out that in Brooklyn Stillman had been part of the Orthodox underworld, and he left for Iowa after one of his gang’s members was murdered, execution-style. Stillman was a fascinating case — an adopted Colombian street kid and consistent problem and ne’er-do-well who was all but abandoned by the Lubavitcher community when he was arrested. By contrast, the arrest and imprisonment of a “real” Jew with a proud Chabad lineage, Pinchas Lew, caused a tumult in Postville’s Jewish community. The Lubavitchers saw Lew’s imprisonment an unjust kidnapping, and they mustered assistance from their community back in Crown Heights, raising vast sums for Lew’s bail and defense. Bloom describes illegal activities undertaken by the community on Lew’s behalf, like the spoliation and destruction of evidence that clearly implicated Lew in the crime spree. In the end, Lew received little punishment for his crime because Stillman was essentially bribed by the community to take the fall for the whole incident. Stillman and Lew vanished from the memory of the Iowa Lubavitchers — to merely mention them, as Bloom found out, was tantamount to anti-Semitism and insulting the Lubavitchers. Bloom was astounded by the collective indifference of the Lubavitchers to the crimes; they never checked up on the victims, expressed remorse, or even so much as offered them some kosher beef. Instead, the Jews militantly supported their criminals (at least Lew), and, as always, ignored those whom they had harmed. Aaron Rubashkin would only declaim to Bloom, “no matter what we do, the goyim always find fault with us.” Indeed, it is precisely when Bloom began researching and putting the story of the Stillman-Lew case together that the Lubavitchers cut him off altogether.

But in the end, what really pushed Bloom over the edge was how the Lubavitchers, in his view, sought to take advantage of a locally respected Jewish doctor’s death as a publicity stunt. “Doc” Wolf had served northeastern Iowa for fifty years and was a thoroughly assimilated Jew and widower. In his last dying days, Doc Wolf had asked the Lubavitchers to provide him some homemade Jewish food. He got the food — and then some. The Lubavitchers sent dozens of men to minister to him and sought to make him one of their own. They turned his hospice room into a turnstile of Rabbis praying with — and over — Doc Wolf. Not able to push them out — and perhaps lacking the mental acuity to do so — Doc Wolf tolerated their presence for his last few days. Bloom argues that the motivation to minister to Doc Wolf was the Lubavitchers’ view that if they could claim the well-regarded local doctor as their own, it would help in the upcoming annexation vote that was basically seen as a referendum of the locals on the Jews. I think Bloom discounts the sincerity of the Lubavitchers, however, because they probably believed that they were doing right by a wayward Jew in his last hours. Only after he died did Doc Wolf’s secular children forcibly remove the Lubavitchers from Doc Wolf’s room and still-warm body.

The annexation measure eventually passed but it did not make that much of a difference between the Jews and the locals. As a post-script (written a few years later in 2001), Bloom describes the tensions as persisting. The problems associated with the plant had continued, and the changes to the community from the influx of illegal immigrants (Russian, Ukrainian, Mexican, and then Somali) changed the once-sleepy White town of Postville forever. What happened afterwards is even more interesting — in 2008, the federal government ordered a massive immigration raid on the plant and hundreds of people were arrested, including Aaron Rubashkin’s son. Eventually, Sholom Rubashkin was sentenced to prison only to have President Trump pardon him in 2017. Today, the plant is still Kosher although run by a different Jewish group — and Postville continues to have a large Hasidic community.

* * *

Postville is compelling read — I finished it over two days because I could not put it down.

Several themes stand out that warrant further consideration — the first among them is the personal turmoil of the author. Postville, when it came out, generated a lot of interest — reviews in The New York Times and other publications showed that the book touched a nerve about diversity and inclusion in the United States. What I found interesting about some of those reviews as I read them is that the author’s personal story was deemed by some to an intrusion in the overall story of Postville. Some reviewers felt that the book dwelt on Bloom’s inner conflict too much. I find myself in vigorous disagreement with that view. Bloom’s inner conflict — his biographical relationship to the Postville drama — was as much the story as was the conflict between the Hasidic Jews and native Iowans. In many ways, Bloom was the most interesting character in Postville — a sort of tortured and conflicted soul who related the broader conflict through the prism of his turmoil. In a sense, he was the most honest of brokers in telling this tale because the conclusion he reached was not the one he necessarily wanted to reach. In that, Bloom was acutely conscious of his own seemingly traitorous conduct in airing, as it were, the “dirty laundry” of the Jews in publishing Postville. And in the Jewish community, the role of traitor is especially odious, and I give Bloom credit for being willing to withstand that role even if it will stay with him for the rest of his life among most Jews.

But Bloom’s story is more than the turmoil — it is the source of that turmoil, which, at least in a sense, transcends Judaism. Bloom was navigating the threadbare meaning within the secular life and searching for some cure to it. All secular people face, whether they know it or not, the implications of their “faith” — that is, they face the realization that they have embraced a “faith” that posits that life has no essential meaning, that truth has no stable source, that morality is little more than opinion and convention, and that all we are is what we see. For an honest and sensitive secularist, there is a heartbreak within that worldview. No one wants to admit that their life — or the lives of their loved ones — is meaningless, but the materialist ethos of our secular age necessarily implies it. Parenthetically, while some may argue that secularism and irreligion are not overlapping circles, I have yet to meet a committed secularist who was not, at the same time, an irreligious materialist. To some secularists, we should just grow up and face it — life has no meaning, so let us enjoy it and not be overwrought by its the portents of its dismal reality. To others, meaning punctuates too much to be ignored and there exists a palpable tension between that feeling and the implications of meaninglessness. Bloom strikes me as the latter — he wanted meaning, he wanted purpose, he wanted to believe but he found in the Hasidic Jews meaning and purpose that were deeply offensive. In a sense, years of secularism have taken hold of his life and heart — he was essentially egalitarian. Thus, even if meaning and purpose were lacking, he could never find it in a religion that was essentially exclusionary.

His attempt, however, to give Hasidic Judaism a “chance” — at least I thought — was very telling. While I object to the ugliness at the heart of Talmudic Judaism, I feel much in common with it as a Traditional Catholic. My belief, and theirs, in the stark and abiding reality of God is a commonality. My belief, and theirs, in the bankruptcy of the secular world is another. My belief, and theirs, that we must follow the whole of God’s commandments no matter the cost is yet another. My belief, and theirs, that we should not count the cost of children but see each one as a supreme blessing from God is another. Finally, the belief in a rigorous morality, a hierarchal and teaching religion, and a life steeped in prayer for the glory and worship of God are more still. Serious Talmudic Jews, such as the Postville Jews, would dismiss me a non-entity and polytheist, and, in turn, I dismiss them as the blind and stubborn descendants of those who denied the messianic and divine reality of Jesus Christ. All the same, I have, at least on a practical level, more in common with them than I do with Stephen Bloom. And, in that sense, I am for more forgiving towards them than Bloom is — he did not merely reject them, he ratted on them and conveyed to the world the things that Jews say comfortably and discretely to only one another. In a sense then, he really did write a book that savaged them — perhaps not unfairly, but certainly uncharitably.

* * *

Another theme that fascinated me about Postville was its depiction of the death of a type of America — a homogeneous America that was marked by the yeoman farmer and local businessman. Small town and rural America before the opioid crisis, before the brain drain, before the sexual revolution, and before Walmart and the shopping mall. There was an element of Postville, Iowa as the last outpost of De Tocqueville’s America — a place where the farm-to-market road was not merely an historical signpost or road name. That America is all but gone — it is a place of changing demographics, addiction, disability, and Trump country. MAGA is a cheap substitute for the time when Americans were genuinely free and independent — and the rearguard action that is MAGA is a political and cultural death rattle for places like Postville. Indeed, the Whites of Postville are aging and contracepting — the high school undoubtedly is filled with Somalis, Mexicans, and other non-Whites. Not that I lament the American dream extending to others; I do not.; But the loss of Postville and the countless other rural places like it is a definitive sign of the demise of at least one version of America. If this is progress, it does not feel like it. I liked the world with Postville, as it was; and I think they should exist somewhere.

If Postville is a death, it is also a birth — a new America is being born there and elsewhere. Setting aside whether it is a better America, it is a different America to say the very least. Homogeneity and heterogeneity are dirty words unless we apply them panegyrically to the cult of diversity. We have no choice, praise diversity or else. So that Postville is now home to many languages, many cultures, many “others” is axiomatically good. And what Postville once was — an enclave of White Christian America — is axiomatically worse.

I happen to live in one of the most diverse places in America. I do not resent it — or the “other” — but I do not celebrate it either. The reality is that people tend to stick with other people most like them in terms of race, religion and, to a lesser extent, socio-economic station. In my town, we are “diverse” inasmuch as we have virtually the entire world’s population represented in microcosm in a small city but, at the same time, there is little overlap in the meaningful social interactions between these groups. It remains to be seen whether a land of many cultures can persist where one culture was once the norm. Certainly, at a minimum, the death of White America as epitomized by Postville’s collapse and the birth of the new multi-racial and multi-cultural America portends new and dramatic ways of living — less trust, less communication, less interaction, and less confidence. And all of that takes place in what is becoming a racial spoils system in which the various groups compete with each other for competitive advantage.

No, I am not bullish on the future of the multi-cultural paradise that liberalism is constructing on the ashes of the old America. Indeed, I am convinced that it portends an impossible situation that will not end well.

But homogeneity, in its racial or religious form, is far from dead. There is something to be said for the Hasidic Jews — and all fervent believers of virtually any type — in this new America. While the multi-racial and multi-cultural America is far more liberal and hostile to religion, and while secularism touches more and more Americans, a distinct and pugnacious religious minority (or minorities) is being born. Hasidic Jews are different from all of the Jews that came before them in the United States — they are militantly Jewish and refuse to make any compromises in the ways that past Jews undoubtedly did. Traditional Catholics are similarly militant. Other offshoots, for the lack of a better word, are taking root all over the country. While the morass of people is slowly and imperceptibly saying “no” to organized religion, a small minority within each tradition is reacting combatively, and they are persevering and growing.

Because of secularism’s hedonism and sterility, the growth of these micro-groups will soon begin to mushroom for two reasons. First, they have children (lots of them). When the average American family is well below the replacement rate of fertility of 2.1 children (because, after all, children exact a sacrifice which is inconsistent with a narcissistic culture), Hasidic Jews, the Amish, Traditional Catholics, and some White nationalists are having seven, eight or more children. And they are also happily rejecting feminism, homosexuality, modern culture, and divorce. The demographic exponential effect of large families birthing many children who, in turn, have large families will be felt much sooner than people realize. Second, an assertive, confident, and happy minority will attract more and more from the doldrums that is the secular hell of hedonism, meaninglessness, and nihilism. The Hasidic Jews will continue to make inroads among secular Jews; Traditional Catholics will do the same among the mass of lapsed and semi-religious Catholics; and racially conscious Whites will attract adherents as they see the burgeoning anti-White hate all around them. The new America will be confusing and hostile, but it will not be able to match the militancy of these groups who know who they are and resist contemporary liberal culture in every conceivable way. In a strange sense, I am comforted by the Hasidic rise in Postville and places like it — not because, of course, I want to live near them or condone their attitudes and behavior, but because they are a brand of Judaism that is growing wildly and rejecting secularism forcefully. In that, Hasidism represents just a type of rejection that transcends Judaism — one in which I myself am participating.

Postville and the takeover of the town by militantly religious Jews is interesting — but the themes it explores could have been written about the community of Traditional Catholics who similarly took over a Kansas town only a few years earlier. Indeed, in a feature article of the January/February 2020 Atlantic magazine Emma Green explored how an outside and militant Catholic group overwhelmed a small Midwestern farming town. The overlapping themes are there — exclusion, self-righteousness and assertiveness, fecundity in the extreme and the accusation of a cult-like atmosphere. As times goes by, I suspect that we will see more intentional communities like Saint Marys, Kansas and Postville, Iowa as militantly religious seek to live their lives in common with like-minded co-religionists.

* * *

Another theme that is uniquely Jewish is that of food. Of course, the premise of the Hasidic relocation was based upon the preparation and slaughter of Kosher food for religious Jews, but food is seemingly lurking on every page. Bloom himself reduces his attachment to Judaism to the food of his youth — to the traditional foods of the Jews. The Shabbat dinner, which is the central meal of the Jews each week, stands prominently in the description of the lives of the Hasidic Jews. I must not be the first person to make the connection that the Jewish ritual of Shabbat dinner — its meaning and importance — must provide some antecedents for the Catholic ritual of the eucharistic meal and sacrifice. In a shadowy sense, the Shabbat dinner, and the Catholic Mass share important connections.

Bloom finally cuts himself off from the Lubavitchers, psychologically anyway, during the long discourse that takes place over Shabbat dinner. For the native Iowans, their food — and ironically enough, the pig — are central to their lives as well. Everything that moves the story seems to involve food, or dinners, or coffee shops. The Doc Wolf incident itself was motivated by the old and dying Jew’s desire for some traditional and authentic Jewish food. While I like to eat, like any human being, I cannot relate to the significance of food for Jews. It is not a judgment on my part, but rather an observation. Food is frequently on the mind of the author.

* * *

The Hasidic contempt for the gentile is palpable throughout Postville. And in this, the ultra-orthodox stand in a long tradition drawing similar conclusions. According the one source, which appears to be consistent with the Hasidic view outlined in Postville, gentile and Jewish souls are very different — ontologically different. For example, “the people of Israel, the Zohar states, possess a living, holy, and elevated soul (“nefesh ḥayah kadisha ila’ah”), as opposed to the other nations, who are described as akin to animals and crawling creatures, which lack this “Divine” soul and possess only an “animal” soul.” See The Soul of a Jew and the Soul of a Non-Jew by Rabbi Hanan Balk, Ḥakirah, the Flatbush Journal of Jewish Law and Thought. For a variety of reasons, I have seen any number of Jewish sources that have indicated that the souls of Jews and gentiles are different, and, as such, Jews and gentiles are creatures of a different kind. The Jew is, accordingly, a spiritualized creature whose very essence is touched by God; the gentile by contrast is not and, as such, is likened to having an existence that is more animal-like.

These sources state a principle that is, on its face, not biologically grounded per se — who is a Jew is, more or less, assumed. One thing that has always interested me is whether the concept of a Jewish soul is the same as the definition of Jewishness. Would, for example, a man born of a Jewish father and a gentile mother have half a Jewish soul? Would the fact that Jewishness is typically deemed passed matrilineally mean that such a “half-breed” would have the “animal” soul of the gentile or something else? Does only a Jewish woman have the power to pass a Jewish soul down to her child — leaving Jewish men bereft of that power? To be fair, there are sources, and even the article cited above, that make clear that there is no consensus on this point, but the fact that this is something deeply embedded with Hasidic Judaism and the Jewish psyche is deeply disturbing. If it is axiomatic to condemn the Nazis for their dehumanization of Jews as “sub-humans,” what can we say of Jews and their brand of Judaism that say that non-Jews are essentially animals? Is that as objectionable? And, if not, why?

For those who pay any attention, the idea of a Jewish superiority complex should not be surprising. “Chosen-ness” evidently carries with it the implication of “un-chosen-ness,” which means necessarily that gentiles were not chosen. Interestingly enough to me, I have always puzzled over why Jews seem to think that their “chosen-ness” carries with it a superiority — as if God chose them because they were special or different. If the Christian charge is that Jews misunderstand seemingly everything about God, it certainly seems to this Christian that they misunderstand that God did not elevate them because they were different or more special; they became different and more special because God elevated them. But that elevation was never meant to be invitation to glory in themselves as if they were better than other men; it was a responsibility to bring the light of God’s glory to the nations, which, of course, they did in Jesus Christ. What seems lacking — profoundly — among Jews is humility. Their insufferable pride, which was on display in Postville, is there for anyone with eyes to see. And it is profoundly unholy.

* * *

Another theme that stood out to me was the obtuseness of Jewishness versus the liberalism of Jewishness. It goes without saying that the Hasidic Jews are not the majority of Jews in the United States or the world — if current demographic trends continue, they might be — but we are probably some time off from that now. Bloom became central to this conflict of Jewish liberalism and Jewish insularity — and, to his credit, he “walked the walk” when it came to what side he chose. I think Bloom is relatively unusual, even as a secular, liberal Jew, because he became the Frank Serpico of the Jews — a complete turncoat. Anyone who reads Postville — religious, non-religious, anti-religious — cannot help but be disgusted with the Hasidic Jews and everything about them. And Bloom is so unusual because my sense is that most liberal Jews like him would never do what he has done because there is a deep hypocrisy that runs through liberal Judaism that condemns every form of tribalism (in the most vicious way) except their own. Bloom took the Hasidic tribalism to task and that makes him someone very different. For example, most liberal Jews see no contradiction in supporting the transparently discriminatory practices of the ethnocentric state of Israel — the tiny and sovereign enclave of Jews increasingly dominated by Orthodox and ethnonationalist Jews much like the Hasidim — while excoriating any political aspirations for other groups to attain a similar place of homogeneous existence and perpetuation.

In the end, Bloom paints a horrible picture of Hasidic life and values. And, for the non-Jew anyway, reading and internalizing the reality of the Postville Jews cannot help but force people to question what they think they know about the Jews generally. True enough, Bloom critiqued his “own,” but the Hasidic Jews are not a different species of Jews — they are just a more extreme version of already existing attitudes among Jews (with the clear implication that even non-Hasidic Jews maintain some of these attitudes, even if more muted and closeted — as indicated by the broad support enjoyed by Orthodox, ethnonationalist Israel within the Jewish diaspora in the West).

It remains to be seen whether Jewish liberalism has a future — clearly, Hasidic Judaism does. My experience of Judaism has taught me that it exerts a gravity unto itself over those born into it — even among liberal Jews. But liberal Jews and Hasidic Jews are literally worlds apart in spirit and practice. Whether liberal Judaism can survive the varied impacts of assimilation, intermarriage, and socio-political distances from Talmudic Judaism is an open question. So is how long the cognitive dissonance between the putative liberal values of most secular Jews and the tribalist predicates for continued support for Israel and Jewish separation can last.

I have read Postville (had to but it in hardback-no kindle version) and I reccomend it. It is a fantastic examination of Jewish behaviour. Also research what the Jews did to the town of Postville after the town rezoned the slaughterhouse- it is now a complete hellhole. Such incidents include running methamphatamine labs in town.

Read Postville everyone.

Sholom Rubashkin had his 27 year sentence commuted to just 8 years served as one of Trump’s very first actions in his role as President, a commutation that was a high bipartisan priority. Jacob Goodwin of Charlottesville fame will likely serve the same time for defending an elderly man from assault, but Rubashkin was convicted of bank fraud, mail fraud, wire fraud, money laundering, and his illegal operations involving animal cruelty, food safety, environmental safety, illegal child labor, and the “undocumented” resulted in the largest ICE raid in American history while some of his cohorts escaped to Israel. Only G_D knows how many tax payer dollars and resources were used to confront the Jewish criminality that turned Postville upside down! So in comparing Rubashkin to Goodwin, we can now ascertain the 21st Century meaning of American justice and privilege.

Plenty of Jewish resources will likely confirm that only about 0.3% of the American population REQUIRES kosher certified foods to serve their religious observance, but the many fine kosher related articles on TOO’s website cite surveys indicating that 39% of consumers object to any religious intervention taking place in the production of their food. So if the “Economy of Scale” of big business can accommodate kosher certifying nearly everything we find in the supermarkets today, including countless inedible items like soaps, detergents, and food wrap, then businesses could be able to yield a healthy profit marketing religious-neutral products (free of Hekhshers or kosher seals, i.e. NKC) to cater to that large 38% group. But that would require transparency and honesty by the corporations and kosher awareness amongst the people, for the existing paradigm continues because of deception. Hardly anyone knows, and not enough people who do know are sharing their kosher [certification] awareness.

The kosher industry began in early 1900s America with boycotting, violence, rioting, and organized crime, resulting in the highly shrouded but profitable religious industry of today. Even the ADL has cited this criminally-laced kosher movement in honoring Jewish Heritage month. But if a patriotic American wished to simply boycott a brand of peanut butter tainted by kosher agencies because the Orthodox Union (OU Kosher) RESOLUTELY supported convicted spy Jonathan Pollard, he couldn’t if he did his shopping at the supermarket. All name brand peanut butters are kosher certified, and the same situation holds true for a majority of food items at the grocery store. So in a normal economy, it should be challenging for the 0.3% to find their religiously certified goods. But in our American economy, everything is upside down…just like Postville, Iowa.

If author Stephen Bloom was slightly disturbed about the blatant Separatism between the Orthodox and the goyim – much like that proscribed in the rabbinical kosher laws like Bishul Akum and Stam Yainom – would he be upset if the American majority began “Bud Lite” styled boycotting as a last effort of American Privilege? And would it be christened “The Goycott?” Take a look and share: https://www.bitchute.com/video/XDSMA0PBDrfI/

I grew up in New York City and unfortunately had some deals with Hasidic Jews. They are the most hateful, condescending, arrogant and cheapest people I’ve ever seen. I’m Jewish on my Dad’s side, but military service changed me, just as it changed him back during World War Two. Like him, I became appalled at the continous bad behavior of many Jews. Seems to me that members of this weird desert cult don’t have much in a way of having a conscience; at least from a Christian perspective. Non Jews are just there to be used

The race war is escalating, most recently in France. Have the French embarked on a solution? Of course not. Just like the Europeans in Britain, USA, Canada, Italy, etc. continue to not end this race war. Why? Because Europeans, whether they are French, English, American, Canadian, Italian, etc. do not care about Europeans, do not even care about their European children. Remember that every time these events occur (riots, burning, killings, maiming) Europeans are harmed. Tunisians are deporting their unwanted, non-Tunisians. French are not. Tunisians think Tunisia is for Tunisians; French think France is for everybody. So, that is the reason the Europeans, whether it’s the French, English, Italian, American, Canadian, etc. continue to be harmed by not reclaiming their homelands. It’s about survival & we Europeans, as a collective, don’t have what it takes to ensure the survival of our European Race.

“Demography is destiny.”

I believe it was the French philosopher Auguste Comte, 1798-1857, who warn us.

A satanic power is working in secret to resurrect Hitlerism and plunge the world into World War III. Thrice-maligned and crucified Lord God in heaven, O thou great Jewish spirit, stop this danger! https://www.thetrumpet.com/27855-the-nazi-billionaire-family-behind-germanys-far-right

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Philadelphia_Trumpet

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Philadelphia_Church_of_God

The Nazis even prevented degenerate Weimar-Berlin from becoming the world center of Jewish “fashion,” writes “Shlomit Lasky.” https://www.dw.com/en/how-the-nazis-destroyed-berlins-thriving-fashion-industry/a-66172345

The lost “Eldorado”, now available only via your certified Netflix account. Golden times of Jewish fashion and homosexual permissiveness, all erased by the racial mania of the demonic Antichrist Adolf Hitler! https://news.google.com/search?q=netflix%20eldorado&hl=en-US&gl=US&ceid=US%3Aen

https://www.breitbart.com/europe/2023/07/08/woke-christianity-archbishop-of-york-brands-lords-prayer-oppressively-patriarchal/

http://www.renegadetribune.com/pastor-says-the-great-replacement-theory-is-an-abomination-and-white-people-need-to-repent/

Just watch a reporter define racism as someone who says that their race is superior to other races. Therefore wanting Japan for the Japanese, Ireland for the Irish, etc. is not racism. Therefore, why aren’t Europeans from Europa to Australia reclaiming their homelands?

https://nypost.com/2023/07/11/chicago-suburb-first-to-start-reparations-payouts/

“Evanston Mayor (((Daniel Biss)))”, wow.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Daniel_Biss

The author says he does no begrudge “the American dream extending to others.”

The problem is that the more it is extended to more non-European non-Whites the more it ceases to be American and a dream. It is no longer Groucho Marx’ exclusive club of which they wished to be members precisely because it did not accept them, and they become vociferously unhappy blaming everything except their presence in it and the changes they imposed upon it to make it a “vibrantly diverse” and “jew-friendly” social and cultural environment.

This is great Bernard. The book is now on my reading list.

When I was eight years old, we moved from Brooklyn to a town in Orange County, New York which is about an hours drive or more, depending where you are in the county. It was Mayberry back then, in the 70s, if you remember the old Andy Griffith show.

Some years ago, Hasidic Jews started moving to the towns of Monroe, Blooming Grove, and that area of southern Orange County. As they did in Postville, they did there. They build cheap ghettos in these bucolic towns, they know every trick in the book to get as much social services as they need from the local towns and the government. What happens is, is that the local population winds up paying for its own demise. Taxes go way up to support the Jews, and because the Jews have large families, their stinky ghettos just keep getting bigger. All of the real estate prices plummet and when that happens, guess who buys up all of the properties from the goyim, many of whom, now underwater financially who now can’t afford the taxes? You guessed it.

The Jews do this everywhere they go. Google it if you’re interested. The name of the town is Kyris Joel which used to be a part of Monroe.

They also have done this in Ramapo, New Jersey, Suffren, Monsey, New York, Jackson, New Jersey, and the list goes on.

And of course, when the locals raise opposition, they are branded as “anti-semites.

Thank you, Mr. Smith .

Do you believe that it is possible to solve the JQ ?

The biggest part of the problem is described right at the beginning of the article. The good people of Postville welcomed the Hasidim because the town was declining and the kosher slaughterhouse would be good for ‘bidness’. Yeah, it was good for ‘bidness’, the bidness of the diversity racket. The people of Postville and similar towns would have been better off accepting the decline and doing the best they could rather than welcoming their own destruction for the money they thought the newcomers would bring, which they didn’t bring anyway.

The same story has been repeated all across the country especially as the American industrial base was sold off starting with the Reagan Administration, devastating much of America. An example of this is the city of Bridgeport, Conn., a small industrial city whose citizens made excellent machine tools and precision instruments found in machine shops all over the country and also exported widely. As cheaper Japanese tools began replacing domestic products in the late 1960’s Bridgeport and cities like it lost population as local companies closed or moved away. Local politicians clamored to let wogs immigrate to Bridgeport because from their point of view the demographics didn’t matter. Numbers of people mattered for the Federal dollars allocated based upon population numbers i.e. more people, more Federal dollars and more representation in Congress.

The predictable result by the late 1970’s was a ruined city filled with nasty colored people whose only businesses were sub shops, liquor stores, muffler shops, selling lottery tickets, drug dealing and crime. Bastardy and the welfare ‘bidness’ along with scumbag lawyers suing for injuries and paternity were thriving. The machine tool business synonymous with Bridgeport and the people who created them were gone replaced by Third World shabbiness and destruction.

The pursuit of money i.e. greed was at the root of these problems. Cheaper products from Asia ruined cities in America. Cheap Mexican labor picking crops in California and elsewhere turned California permanently Democrat as Whites fled, replaced by hispanics. Bidness made short term profits at the cost of long term destruction of the country. Unfettered capitalism was finally unleashed, the glorious “free market” as the scumbag Republicans crowed about in the 1980’s. The country was flooded with the Third World driving down labor costs (i.e. wages) temporarily increasing corporate profits.

St. Paul summed it up: :Love of money (Not money itself) is the root of all evil.

Now the U.S. is a shambles while the U.S. Government confronts China over Taiwan, 7,000 miles away from the U.S. while fighting a proxy war against Russia at the same time. This is insane especially since the U.S. industrial base that supported the U.S. military in the 20th century is now gone. The geniuses in Washington don’t care, they act as though it’s still the U.S. of 1960 they are running. The Ozzie and Harriet, White supremacist USA they hate so much that also produced the formidable American military and technological power of the 20th century.