Interview with Kevin Barrett on Jewish Hyper-ethnocentrism

Kevin Barrett interviewed me on my article “The Extreme Hyper-Ethnocentrism of Jews on Display in Israeli attitudes toward the Gaza War.”

Jewish Ethnocentrism

Kevin Barrett interviewed me on my article “The Extreme Hyper-Ethnocentrism of Jews on Display in Israeli attitudes toward the Gaza War.”

If you know anything about traditional Jewish ethics (i.e., Jewish ethics before a great deal of intellectual work was performed aimed at providing a rationale for Judaism as a modern religion in the West—apparent in the Wikipedia article on Jewish ethics), you know that pre-Enlightenment Jewish ethics was entirely based on whether actions applied to the ingroup or the outgroup. Non-Jews had no moral worth and could be exploited or even murdered as long as doing so did not threaten the interests of the wider Jewish community. I have written a great deal on Jewish ingroup morality, beginning with the Chapter 6 in A People That Shall Dwell Alone:

Business and social ethics as codified in the Bible and the Talmud took strong cognizance of group membership in a manner that minimized oppression within the Jewish community, but not between Jews and gentiles. Perhaps the classic case of differential business practices toward Jews and gentiles, enshrined in Deuteronomy 23, is that interest on loans could be charged to gentiles, but not to Jews. Although various subterfuges were sometimes found to get around this requirement, loans to Jews in medieval Spain were typically made without interest (Neuman 1969, I:194), while those to Christians and Moslems were made at rates ranging from 20 to 40 percent (Lea 1906-07, I:97). Hartung (1992) also notes that Jewish religious ideology deriving from the Pentateuch and the Talmud took strong cognizance of group membership in assessing the morality of actions ranging from killing to adultery. For example, rape was severely punished only if there were negative consequences to an Israelite male. While rape of an engaged Israelite virgin was punishable by death, there was no punishment at all for the rape of a non-Jewish woman. In Chapter 4, it was also noted that penalties for sexual crimes against proselytes were less than against other Jews.

Hartung notes that according to the Talmud (b. Sanhedrin 79a) an Israelite is not guilty if he kills an Israelite when intending to kill a heathen. However, if the reverse should occur, the perpetrator is liable to the death penalty. The Talmud also contains a variety of rules enjoining honesty in dealing with other Jews, but condoning misappropriation of gentile goods, taking advantage of a gentile’s errors in business transactions, and not returning lost articles to gentiles (Katz 1961a, 38).[ii]

Katz (1961a) notes that these practices were modified in the medieval and post‑medieval periods among the Ashkenazim in order to prevent hillul hashem (disgracing the Jewish religion). In the words of a Frankfort synod of 1603, “Those who deceive Gentiles profane the name of the Lord among the Gentiles” (quoted in Finkelstein 1924, 280). Taking advantage of gentiles was permissible in cases where hillul hashem did not occur, as indicated by rabbinic responsa that adjudicated between two Jews who were contesting the right to such proceeds. Clearly this is a group-based sense of ethics in which only damage to one’s own group is viewed as preventing individuals from profiting at the expense of an outgroup. “[E]thical norms applied only to one’s own kind” (Katz 1961a, 42).

Evolutionary psychologist/anthropologist John Hartung, referenced above, has continued his work on Jewish ethics on his website strugglesforexistence.com; note particularly “Thou Shalt Not Kill … Whom?.” The Jewish double ethical standard has been a major theme of anti-Semitism throughout the ages, discussed in Chapter 2 of Separation and Its Discontents; these intellectuals are good examples:

Beginning with the debates between Jews and Christians during the Middle Ages (see Chapter 7) and reviving in the early 19th century, the Talmud and other Jewish religious writings have been condemned as advocating a double standard of morality, in addition to being anti-Christian, nationalistic, and ethnocentric, a view for which there is considerable support (see Hartung 1995; Shahak 1994; PTSDA, Ch. 6). For example, the [Cornell University] historian Goldwin Smith (1894, 268) provides a number of Talmudic passages illustrating the “tribal morality” and “tribal pride and contempt of common humanity” (p. 270) he believed to be characteristic of Jewish religious writing. Smith provides the following passage suggesting that subterfuges may be used against gentiles in lawsuits unless such behavior would cause harm to the reputation of the entire Jewish ingroup (i.e., the “sanctification of the Name”):

When a suit arises between an Israelite and a heathen, if you can justify the former according to the laws of Israel, justify him and say: ‘This is our law’; so also if you can justify him by the laws of the heathens justify him and say [to the other party:] ‘This is your law’; but if this can not be done, we use subterfuges to circumvent him. This is the view of R. Ishmael, but R. Akiba said that we should not attempt to circumvent him on account of the sanctification of the Name. Now according to R. Akiba the whole reason [appears to be,] because of the sanctification of the Name, but were there no infringement of the sanctification of the Name, we could circumvent him! (Baba Kamma fol. 113a)

Smith comments that “critics of Judaism are accused of bigotry of race, as well as bigotry of religion. The accusation comes strangely from those who style themselves the Chosen People, make race a religion, and treat all races except their own as Gentiles and unclean” (p. 270).

[Economist, historian, sociologist] Werner Sombart (1913, 244–245) summarized the ingroup/outgroup character of Jewish law by noting that “duties toward [the stranger] were never as binding as towards your ‘neighbor,’ your fellow-Jew. Only ignorance or a desire to distort facts will assert the contrary. . . . [T]here was no change in the fundamental idea that you owed less consideration to the stranger than to one of your own people. . . . With Jews [a Jew] will scrupulously see to it that he has just weights and a just measure; but as for his dealings with non-Jews, his conscience will be at ease even though he may obtain an unfair advantage.” To support his point, Sombart provides the following quote from Heinrich Graetz, a prominent 19th-century Jewish historian:

To twist a phrase out of its meaning, to use all the tricks of the clever advocate, to play upon words, and to condemn what they did not know . . . such were the characteristics of the Polish Jew. . . . Honesty and right-thinking he lost as completely as simplicity and truthfulness. He made himself master of all the gymnastics of the Schools and applied them to obtain advantage over any one less cunning than himself. He took a delight in cheating and overreaching, which gave him a sort of joy of victory. But his own people he could not treat in this way: they were as knowing as he. It was the non-Jew who, to his loss, felt the consequences of the Talmudically trained mind of the Polish Jew. (In Sombart 1913, 246)

… Pioneering German sociologist Max Weber (1922, 250) also verified this perception, noting that “As a pariah people, [Jews] retained the double standard of morals which is characteristic of primordial economic practice in all communities: What is prohibited in relation to one’s brothers is permitted in relation to strangers.”

A common theme of late-18th- and 19th-century German anti-Semitic writings emphasized the need for moral rehabilitation of the Jews—their corruption, deceitfulness, and their tendency to exploit others (Rose 1990). Such views also occurred in the writings of Ludwig Börne and Heinrich Heine (both of Jewish background) and among gentile intellectuals such as Christian Wilhelm von Dohm (1751–1820) and Karl Ferdinand Glutzkow (1811–1878), who argued that Jewish immorality was partly the result of gentile oppression. Theodor Herzl viewed anti-Semitism as “an understandable reaction to Jewish defects” brought about ultimately by gentile persecution: Jews had been educated to be “leeches” who possessed “frightful financial power”; they were “a money-worshipping people incapable of understanding that a man can act out of other motives than money” (in Kornberg 1993, 161, 162). Their power drive and resentment at their persecutors could only find expression by outsmarting Gentiles in commercial dealings” (Kornberg 1993, 126). Theodor Gomperz, a contemporary of Herzl and professor of philology at the University of Vienna, stated “Greed for gain became . . . a national defect [among Jews], just as, it seems, vanity (the natural consequence of an atomistic existence shunted away from a concern with national and public interests)” (in Kornberg 1993, 161).

So we should not be surprised to find that a great many Jews view Palestinians as having no moral worth. They are seen as literally not human, as noted by the prominent Lubavitcher Rebbe Schneerson:

We do not have a case of profound change in which a person is merely on a superior level. Rather we have a case of…a totally different species…. The body of a Jewish person is of a totally different quality from the body of [members] of all nations of the world…. The difference of the inner quality [of the body]…is so great that the bodies would be considered as completely different species. This is the reason why the Talmud states that there is an halachic difference in attitude about the bodies of non-Jews [as opposed to the bodies of Jews]: “their bodies are in vain”…. An even greater difference exists in regard to the soul. Two contrary types of soul exist, a non-Jewish soul comes from three satanic spheres, while the Jewish soul stems from holiness. (see here)

Different species have no moral obligations to each other—predator and prey, parasite and host, humans domesticating cattle and eating meat and dairy products.

This ethic differs radically from Western universalism as epitomized by Kant’s moral imperative: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” Moral universalism is fundamental to Western individualism: Groups per se have no moral status—the exact opposite of Judaism.

Jews may often present themselves as the height of morality, but appearances can be deceiving. From my review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century:

In 1923, several Jewish intellectuals published a collection of essays admitting the “bitter sin” of Jewish complicity in the crimes of the Revolution. In the words of a contributor, I. L. Bikerman, “it goes without saying that not all Jews are Bolsheviks and not all Bolsheviks are Jews, but what is equally obvious is that disproportionate and immeasurably fervent Jewish participation in the torment of half-dead Russia by the Bolsheviks” (p. 183). Many of the commentators on Jewish Bolsheviks noted the “transformation” of Jews: In the words of another Jewish commentator, G. A. Landau, “cruelty, sadism, and violence had seemed

alien to a nation so far removed from physical activity.” And another Jewish commentator, Ia. A Bromberg, noted that: the formerly oppressed lover of liberty had turned into a tyrant of “unheard-of-despotic arbitrariness”…. The convinced and unconditional opponent of the death penalty not just for political crimes but for the most heinous offenses, who could not, as it were, watch a chicken being killed, has been transformed outwardly into a leather-clad person with a revolver and, in fact, lost all human likeness (pp. 183–184). This psychological “transformation” of Russian Jews was probably not all that surprising to the Russians themselves, given Gorky’s finding that Russians prior to the Revolution saw Jews as possessed of “cruel egoism” and that they were concerned about becoming slaves of the Jews.

At least until the Gaza war, Jews have successfully depicted themselves as moral paragons and as champions of the downtrodden in the contemporary West. The organized Jewish community pioneered the civil rights movement and have been staunch champions of liberal immigration and refugee policies, always with the rhetoric of moral superiority (masking obviously self-interested motivations of recruiting non-Whites who could be relied on to ally with Jews in their effort to lessen the power of the erstwhile White majority by making them subjects of a multicultural, anti-White political hegemony; here, p. 26ff).

This weighs heavily on my mind. This Jewish pose of moral superiority is a dangerous delusion, and we must be realistic what the future holds as Whites continue to lose political power in all Western countries. When the gloves come off, there is no limit to what Jews in power may do if their present power throughout the West continues to increase. The ubiquitous multicultural propaganda of ethnic groups living in harmony throughout the West will quickly be transformed into a war of revenge for putative historical grievances that Jews harbor against the West, from the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans to the events of World War II. This same revenge was fatal to many millions of Russians and Ukrainians. It’s the fate of the Palestinians that we are seeing unfold before our eyes. Two recent articles brought this home vividly.

Megan Stack in The New York Times:

Israel has hardened, and the signs of it are in plain view. Dehumanizing language and promises of annihilation from military and political leaders. Polls that found wide support for the policies that have wreaked devastation and starvation in Gaza. Selfies of Israeli soldiers preening proudly in bomb-crushed Palestinian neighborhoods. A crackdown on even mild forms of dissent among Israelis.

The Israeli left — the factions that criticize the occupation of Palestinian lands and favor negotiations and peace instead — is now a withered stump of a once-vigorous movement. In recent years, the attitudes of many Israelis toward the “Palestinian problem” have ranged largely from detached fatigue to the hard-line belief that driving Palestinians off their land and into submission is God’s work. …

But Israel’s slaughter in Gaza, the creeping famine, the wholesale destruction of neighborhoods — this, polling suggests, is the war the Israeli public wanted. A January survey found that 94 percent of Jewish Israelis said the force being used against Gaza was appropriate or even insufficient. In February, a poll found that most Jewish Israelis opposed food and medicine getting into Gaza. It was not Mr. Netanyahu alone but also his war cabinet members (including Benny Gantz, often invoked as the moderate alternative to Mr. Netanyahu) who unanimously rejected a Hamas deal to free Israeli hostages and, instead, began an assault on the city of Rafah, overflowing with displaced civilians.

“It’s so much easier to put everything on Netanyahu, because then you feel so good about yourself and Netanyahu is the darkness,” said Gideon Levy, an Israeli journalist who has documented Israel’s military occupation for decades. “But the darkness is everywhere.” …

Like most political evolutions, the toughening of Israel is partly explained by generational change — Israeli children whose earliest memories are woven through with suicide bombings have now matured into adulthood. The rightward creep could be long-lasting because of demographics, with modern Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews (who disproportionately vote with the right) consistently having more babies than their secular compatriots.

Most crucially, many Israelis emerged from the second intifada with a jaundiced view of negotiations and, more broadly, Palestinians, who were derided as unable to make peace. This logic conveniently erased Israel’s own role in sabotaging the peace process through land seizures and settlement expansion. But something broader had taken hold — a quality that Israelis described to me as a numb, disassociated denial around the entire topic of Palestinians.“The issues of settlements or relations with Palestinians were off the table for years,” Tamar Hermann told me. “The status quo was OK for Israelis.”

Ms. Hermann, a senior research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, is one of the country’s most respected experts on Israeli public opinion. In recent years, she said, Palestinians hardly caught the attention of Israeli Jews. She and her colleagues periodically made lists of issues and asked respondents to rank them in order of importance. It didn’t matter how many choices the pollsters presented, she said — resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict came in last in almost all measurements. …

or nearly two decades — starting with the quieting of the second intifada and ending calamitously on Oct. 7 — Israel was remarkably successful at insulating itself from the violence of the occupation. Rockets fired from Gaza periodically rained down on Israeli cities, but since 2011, Israel’s Iron Dome defense system has intercepted most of them. The mathematics of death heavily favored Israel: From 2008 until Oct. 7, more than 6,000 Palestinians were killed in what the United Nations calls “the context of occupation and conflict”; during that time, more than 300 Israelis were killed.

Human rights organizations — including Israeli groups — wrote elaborate reports explaining why Israel is an apartheid state. That was embarrassing for Israel, but nothing really came of it. The economy flourished. Once-hostile Arab states showed themselves willing to sign accords with Israel after just a little performative pestering about the Palestinians.

Those years gave Israelis a taste of what may be the Jewish state’s most elusive dream — a world in which there simply did not exist a Palestinian problem.

Daniel Levy, a former Israeli negotiator who is now president of the U.S./Middle East Project think tank, describes “the level of hubris and arrogance that built up over the years.” Those who warned of the immorality or strategic folly of occupying Palestinian territories “were dismissed,” he said, “like, ‘Just get over it.’”

If U.S. officials understand the state of Israeli politics, it doesn’t show. Biden administration officials keep talking about a Palestinian state. But the land earmarked for a state has been steadily covered in illegal Israeli settlements, and Israel itself has seldom stood so unabashedly opposed to Palestinian sovereignty.

There’s a reason Mr. Netanyahu keeps reminding everyone that he’s spent his career undermining Palestinian statehood: It’s a selling point. Mr. Gantz, who is more popular than Mr. Netanyahu and is often mentioned as a likely successor, is a centrist by Israeli standards — but he, too, has pushed back against international calls for a Palestinian state.

Daniel Levy describes the current divide among major Israeli politicians this way: Some believe in “managing the apartheid in a way that gives Palestinians more freedom — that’s [Yair] Lapid and maybe Gantz on some days,” while hard-liners like Mr. Smotrich and Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir “are really about getting rid of the Palestinians. Eradication. Displacement.”

The carnage and cruelty suffered by Israelis on Oct. 7 should have driven home the futility of sealing themselves off from Palestinians while subjecting them to daily humiliations and violence. As long as Palestinians are trapped under violent military occupation, deprived of basic rights and told that they must accept their lot as inherently lower beings, Israelis will live under the threat of uprisings, reprisals and terrorism. There is no wall thick enough to suppress forever a people who have nothing to lose.

* * *

Ilana Mercer is a Jewish woman from South Africa who has posted on various conservative sites. Here she states the unmentionable about Israel—and by implication, a very wide swath of Jews living in the West: that sociopathy toward non-Jews is entirely mainstream among Jews. No one should be surprised by this. My only quibble is that real sociopaths have no guilt and even take pleasure in harming others without regard to their religion or ethnicity. But these same Jews who are reveling in slaughtering Palestinians are Jewish patriots and love their own people. But they have an extreme form of ingroup morality—a morality that is intimately linked to what I call Jewish “hyper-ethnocentrism” (e.g., here).

Ilana Mercer at Lew Rockwell.com: Sad To Say, but, by the Numbers, Israeli Society Is Systemically Sociopathic.

In teasing out right from wrong, discriminate we must between acts that are criminal only because The State has criminalized them (mala prohibita), as opposed to acts which are universally evil (malum in se). Israel’s sacking of Gaza is malum in se, universally evil. Gaza is clearly an easy case in ethics. It’s not as though the genocide underway in Gaza could ever be finessed or gussied up.

Yet in Israel, no atrocity perpetrated by the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) in Gaza is too conspicuous to ignore. One of the foremost authorities on Gaza, Dr. Norman Finkelstein, calls Israel a Lunatic State. “It is certainly not a Jewish State,” he avers. “A murderous nation, a demonic nation,” roars Scott Ritter—legendary, larger-than-life American military expert, to whose predictive, reliable reports from theaters of war I’ve been referring since 2002. That the Jewish State is genocidal is not in dispute. But, what of Israeli society? Is it sick, too? What of the Israeli anti-government protesters now flooding the streets of metropolitan Israel? How do they feel about the incessant, industrial-scale campaign of slaughter and starvation in Gaza, north, center and south?

They don’t.

In desperate search for a universal humanity—a transcendent moral sensibility—among the mass of Israelis protesting the State; I scoured many transcripts over seven months. I sat through volumes of video footage, searching as I was for mention, by Israeli protesters, of the war of extermination being waged in their name, on their Gazan neighbors. I found none. Much to my astonishment, I failed to come across a single Israeli protester who cried for anyone but himself, his kin and countrymen, and their hostages. Israelis appear oblivious to the unutterable, irreversible, irremediable ruin adjacent.

Again: I found no transcendent humanity among Israeli protesters; no allusion to the universal moral order to which international humanitarian law, the natural law and the Sixth Commandment give expression. I found only endless iterations among Jewish-Israelis of their sectarian interests.

For their part, protesters merely want regime change. They saddle Netanyahu solely with the responsibility for hostages entombed in Gaza, although, Benny Gantz (National Unity Party), ostensible rival to Bibi Netanyahu (Likud), and other War Cabinet members, are philosophically as one (Ganz had boasted, in 2014, that he would “send parts of Gaza back to the Stone Age”). With respect to the holocaustal war waged on Gaza, and spreading to the West Bank, there is no chasm between these and other squalid Jewish supremacists who make up “Israel’s wartime leadership.”

If you doubt my findings with respect to the Israeli protesters, note the May 11 droning address of protester Na’ama Weinberg, who demanded a change of government. Weinberg condemned the invasion of Rafah and a lack of a political strategy as perils to both hostage- and national survival. She lamented the “unspeakable torture” faced by the hostages. When Weinberg mentioned “evacuees neglected,” I lit up. Nine-hundred thousand Palestinians have been displaced from Rafah in the last two weeks. Forty percent of Gaza’s population. My hope was fleeting. It soon transpired that Weinberg meant citizens of Israeli border communities evacuated. That was the extent of Weinberg’s sympathies for the “slaughter house of civilians” down the road. Hers was nothing but a lower-order sectarian sensibility.

The grim spareness of Israeli protester sentiment has been widely noticed.

Writing for Foreign Policy, an American mainstream magazine, Mairav Zonszein, scholar with the International Crisis Group, observes the following:

‘The thousands of Israelis who are once again turning out to march in the streets are not protesting the war. Except for a tiny handful of Israelis, Jews, and Palestinians, they are not calling for a cease-fire or an end to the war—or for peace. They are not protesting Israel’s killing of unprecedented numbers of Palestinians in Gaza or its restrictions on humanitarian aid that have led to mass starvation. (Some right-wing Israelis even go further by actively blocking aid from entering the strip.) They are certainly not invoking the need to end military occupation, now in its 57th year. They are primarily protesting Netanyahu’s refusal to step down and what they see as his reluctance to seal a hostage deal.’

Public incitement continues apace. Genocidal statements saturate Israeli society. The “lovely” Itamar Ben Gvir has provided an update to his repertoire, the kind chronicled so well by the South Africans (this one included). On May 14, to the roar of the crowd, Israel’s national security minister urged anew that Palestinians be voluntarily encouraged to emigrate (as if anything that has befallen the Palestinians of Gaza, since October 7, has been “voluntary”). He was speaking at a settler rally on the northern border of Gaza, in which thousands of yahoos watched the “fireworks” on display over Gaza, and cheered for looting the land of the dead and dying there.

“It’s the media’s fault,” you’ll protest. “Israelis, like Americans, are merely brainwashed by their media.”

Inarguably, Israeli media—from Arutz 7, to Channel 12 (“[Gazans need] to die ‘hard and agonizing deaths’), to Israel Today, to Now 14 (“We will slaughter you and your supporters”), and the lowbrow, sub-intelligent vulgarians of i24—are a self-obsessed, energetic Idiocracy.

These media feature excitable sorts, volubly imparting their atavistic, primitive tribalism in ugly, anglicized, Pidgin Hebrew. And, each one of these specimen always has a “teoria”: a theory.

Naveh Dromi is a lot more appealing in visage and voice than i24’s anchor Benita Levin, a harsh and vinegary South African Kugel. Dromi is columnist for a Ha’aretz, the most highbrow of Israel’s (center-left) dailies. Ha’aretz once had intellectual ballast. In her impoverished Hebrew, Dromi has tweeted about her particular “teoria”: “a second Nakba” is a coming. Elsewhere she has rasped a-mile-a-minute about “the Palestinians as a redundant group.” Nothing crimsons her lovely cheeks.

Such statements of Jewish supremacy pervade Jewish-Israeli media. But, no; it’s not the Israeli media’s fault. The closing of the Israeli mind is entirely voluntary.

According to a paper from Oxford Scholarship Online, the “media landscape in Israel” evinces “healthy competition” and declining concentration. “[C]alculated on a per-capita basis,” “the number of media voices in Israel,” overall, “is near the top of the countries investigated.”

Israel has a robust, and privately owned media. These media cater to the Israeli public, which has a filial stake in lionizing the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), in which each and every son and daughter serve. For this reason, avers Ha’aretz’s Gideon Levi, in his many YouTube television interviews, the military is the country’s golden calf.

Mainstream public opinion, Levi insists, molds the media, not the obverse.

Levi attests that right-wing and left-wing media are as one when it comes to the subject of the IDF and the Palestinian People. And in this, Israeli media reflect mainstream public opinion. It is the public that wishes to see nothing of the suffering in Gaza, and takes care never to disparage or doubt the IDF. For their part, military journalists are no more than embeds, in bed with the military.

At least until now, Israelis have been largely indifferent to their army’s orgiastic, indiscriminate bloodletting in Gaza. Most were merely demanding a return of their hostages, and the continuance of the assault on Gazans, punctured by periodic cease fires.

So, is Jewish-Israeli society sick, too?

When “88 percent of Jewish-Israeli interviewees” give “a positive assessment of the performance of the IDF in Gaza until now” (Tamar Hermann, “War in Gaza Survey 9,” Israel Democracy Institute, January 24, 2024), and “[a]n absolute majority (88%) also justifies the scope of casualties on the Palestinian side”; (Gershon H. Gordon, The Peace Index, January 2024, Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University)—it is fair to conclude that the diabolical IDF is, for the most, the voice of the Jewish-Israeli commonwealth.

Consider: By January’s end, the Gaza Strip had, by and large, already been rendered uninhabitable, a moonscape. Nevertheless, 51 percent of Jewish-Israelis said they believed the IDF was using an appropriate amount (51%) or not enough force (43%) in Gaza. (Source: Jerusalem Post staff, “Jewish Israelis believe IDF is using appropriate force in Gaza,” January 26, 2024.)

Note: Polled opinion was not split between Israelis for genocide and Israelis against it. Rather, the division in Israeli society appeared to be between Jewish-Israelis for current levels of genocide versus those for greater industry in what were already industrial-levels and methods of murder.

Attitudes in Israel have only hardened since: By mid-February, 58 percent of this Jewish cohort was grumbling that not enough force had been deployed to date; and 68 percent did “not support the transfer of humanitarian aid to Gaza.” (Jerusalem Post Staff, “Majority of Jewish Israelis opposed to demilitarized Palestinian state,” February 21, 2024.) [One wonders if the Biden admin’s humanitarian pier — the one that drifted into the sea shortly after it was installed — was sabotaged.]

Scrap the “hardened” verb. Attitudes in Jewish Israel have not merely hardened, but bear the hallmark of societal sociopathy.

When asked, in particular, “to what extent should Israel take into consideration the suffering of the Palestinian population when planning the continuation of the fighting there,” Jewish-Israelis sampled have remained consistent through the months of the onslaught on Gaza, from late in October of 2023 to late in March of 2024. The Israel Democracy Institute, a polling organization, found that,

‘[D]espite the progress of the war in Gaza and the harsh criticism of Israel from the international community regarding the harm inflicted on the Palestinian population, there remains a very large majority of the Jewish public who think that Israel should not take into account the suffering of Palestinian civilians in planning the continuation of the fighting. By contrast, a similar majority of the Arab public in Israel take the opposite view, and think this suffering should be given due consideration.’ (Tamar Hermann, Yaron Kaplan, Dr. Lior Yohanani, “War in Gaza Survey 13,” Israel Democracy Institute, March 26, 2024.)

Large majorities of the Israeli Center (71 percent) and on the Right (90 percent) say that “Israel should only take into account the suffering of the Palestinian population to a small extent or should not do so at all.”

Let us, nevertheless, end this canvas with the “good” news: On the “bleeding heart” Israeli Left; “only” (I’m being cynical) 47 percent of a sample “think that Israel should not take into consideration the suffering of Palestinian civilians in Gaza or should do so only to a small extent, while 50 percent think it should consider their plight to a fairly large or very large extent.” (Ibid.)

In other words, the general run of the Jewish-Israeli Left tends to think that the plight of Gazans should be considered, but not necessarily ended.

On the facts, and, as I have had to, sadly, show here, both the Israeli state and civil society are driven by Jewish supremacy, the kind that sees little to no value in Palestinian lives and aspirations. …

* * *

Again, any student of Jewish history, Jewish ethics, and Jewish hyper-ethnocentrism should not be surprised by this. The existential problem for us is that we have to avoid the fate of the Russians, the Ukrainians, and the Palestinians. Jews in power will do what they can to oppose the interests of non-Jews of whatever society they reside in, whether by promoting nation-destroying immigration and refugee policy or — when they have absolute power — torture, imprisonment, and genocide.

The contrast between the hyper-ethnocentric Israeli media described by Mercer and the anti-White, utopian, multicultural media in the West, much of it owned and staffed by Jews, couldn’t be greater. Whereas the Israeli media reflect the ethnocentrism of the Israeli public, the media in the West do their best to shape public attitudes, including constant and ever-increasing anti-White messaging — morally phrased messaging that is effective with very large percentages of White people, especially women, likely for evolutionary reasons peculiar to Western individualist cultures (here, Ch. 8). The state of the Western media is Exhibit A of Jews as a hostile elite in the West.

It should be obvious at this point that Western cultures are the opposite of Middle Eastern cultures where ethnocentrism and collectivism reign. Westerners have far less of the ingroup-outgroup thinking so typical of Jewish culture throughout history.

Individualism has served us poorly indeed and has been a disaster for Western peoples. Nothing short of a strong ingroup consciousness in which Jews are seen as a powerful and very dangerous outgroup will save us now.

The Sentencia-Estatuto of 1449: Translated from Spanish to English and with an Introduction by Wilhem Ivorsson

Translator’s Notes:

The reader should keep in mind that this text is 575 years old. Many of the political titles and legal concepts referenced do not have modern equivalents, and the document was written in period-specific legal language, style and custom. The text is not very accessible even for a modern Spanish-speaking audience let alone an English-speaking one. Such being the case, I took a few liberties to increase the readability. This involved slightly rewording certain conjunctive phrasings and adding periods to delineate some tracts that otherwise would not sensibly translate to English; adding qualifying particles between brackets; and periodically omitting a redundant word. I also maintained English grammar rules regarding cases; I always capitalize “Catholic” and “Lord King” whereas the original does not. Aside from these changes, I have strived to retain the original semantic value, tone and structure. For the source text, I primarily used the reproduced copy found in Eloy Benito Ruano’s Toledo En El Siglo XV published by the University of Madrid in 1961. I also consulted the reproduced copy in Antonio Martín Gamero’s Historia de la Ciudad de Toledo published in 1862. Below is a longform translation, but I have also provided a simplified translation that omits less important elements and takes more liberties to achieve greater accessibility. You can read it here. You can also view the original Spanish text here.

Preface

The Sentencia-Estatuto has been highlighted as one of the foundational documents of Spain’s Limpieza de Sangre policies. It was written in June of 1449 during Toledo’s rebellion against the crown. In January the Castilian constable Alvaro de Luna demanded the city provide a loan of one million maravedis to Juan II’s court. The loan was advertised as a means to confront the kingdom’s mounting military threats from Aragon to the Northeast and the Moors to the South. To procure the money for the loan, the city treasurer, Alonso Cota, a converso of Jewish heritage,1 imposed a tax on the commoners at the rate of dos doblas. Many believed that Alvaro de Luna and Alonso Cota “had devised the loan for their own personal gain; Cota was to reap his profit as tax farmer, and Alvaro was to get his bribe from Cota.”2 When Alonso’s men forcefully took the dos doblas from a lowly leather worker,3 the city erupted in protest. Enraged citizens ransacked Alonso Cota’s multiple homes. Afterwards they attacked and pillaged the Magdalena quarter4 where all the wealthy conversos and Jews were known to reside.

A nobleman, Pedro Sarmiento, took charge of the agitated masses and assumed effective control over Toledo. A few conversos took up arms against the rebels and were killed. Others were banished from the city and their homes and property confiscated. Over the next several months Juan II’s and De Luna’s forces undertook a siege campaign against the city. As the Sentencia-Estatuto stated, the royal court waged “a cruel war of blood and fire, of crop destruction and pillaging” against the citizens of Toledo. Periodically, Sarmiento engaged in negotiations with the king for the safe return of the city. One of the stipulations was that Alvaro de Luna be removed from Juan II’s court. As Spanish historian Eloy Benito Ruano explains, it was believed that De Luna had sold a number of public offices to the conversos and that he had “taken over the will of the King” and protected many “heretics and Judaizers.”5 Regarding converso overrepresentation in Juan II’s court, the late Jewish scholar Benzion Netanyahu (Benjamin Netanyahu’s father) said that:

…there can be no doubt that the influence of the conversos in the royal secretaryship was one of the factors determining the appointments of the cities’ chief authorities…the crowning achievement of the conversos in government was attained through their membership in Castile’s royal Council…Toward the end of [Juan II’s reign] they probably comprised no less than a third of its members, reaching at that time the zenith of their influence in determining the actions and policies of the state.6

The Sentencia-Estatuto explicitly stated, referring to the public notaries, that it was “well known to all, that the majority of said notary positions, said conversos tyrannically held and possessed, as much by the purchase with money as by favors and other clever and deceptive means.” The document emphasized that conversos should “especially” be barred from these offices and their “exemptions” which probably involved immunities from certain taxes and related financial obligations.

The Sentencia-Estatuto also rendered conversos ineligible to act as witnesses in court against old Christians. Many modern commentators view this as a historical novelty, but long before the Sentencia-Estatuto, Christians were not allowed to testify against Jews in Rabbinic courts,7 and Talmudic Mesirah laws often forbade Jews from denouncing fellow Jews to non-Jewish authorities. In addition, the Talmud sometimes forbids Jews from testifying against other Jews in secular courts.8 Even today, there is evidence that Jews still culturally adhere to these laws. For example in 2006, Israeli-American real estate investor Solomon Dwek was convicted of felony fraud after trying to steal $50 million from PNC Bank in a check-kiting scheme. Subsequently, he became an FBI informant and his father, Rabbi Dwek, famously denounced him from the pulpit at his synagogue, citing the Talmudic law of moser.9 His father even reportedly said that he would be sitting shiva, a week-long morning ritual, because he considered his son dead.10

While the Sentencia-Estatuto is not explicit on the matter, its statements easily lend themselves to a supposition that conversos would testify in secular courts against old Christians on behalf of fellow conversos in an ethnocentric fashion. With this in mind, the Sentencia-Estatuto outright accused the conversos of systematically taking over Toledo’s government, running it into the ground, and purposefully dispossessing many old Christian nobles:

…through cunning and deceit, [the conversos have] taken and carried off and stolen large and innumerable amounts of maravedis and silver from our king the lord and from his rents, rights, and taxes, and they have destroyed and ruined many noblewomen, knights and hidalgos. Consequently they have oppressed, destroyed, robbed and ravaged all the most ancient houses and estates of the old Christians of this city and its land and jurisdiction and all the realms of Castile, as is well known and as such we regard it. Furthermore, during the time that they have held public office in this city, and its management and administration, the greater part of said city’s centers have been depopulated and destroyed; said city’s own land and centers [have been] lost and alienated. Beyond all this, all the maravedis of said city’s income and property have been consumed in their own interests and properties, in such a manner that all of the country’s wealth and reputation have been consumed and destroyed.

All this said, the Sentencia-Estatuto is sometimes viewed as a post-hoc justification for the Toledans to rob and pillage the city’s wealthy conversos. Benzion Netanyahu claimed that Sarmiento lacked the support of the upper class nobles, and so he seized on the commoners’ animosity toward conversos in order to undermine Alvaro de Luna. He argues that Sarmiento was “a second-rate nobleman, with mediocre estates and moderate income”11 who felt entitled to greater monetary compensation for his past services to the king. In Netanyahu’s view, the rebellion was not an organic event, and Sarmiento premeditated and orchestrated the entire affair because of “hurt feelings” and a fear of “an impending disaster,”12 after he became convinced that De Luna had begun to see him as a political enemy.

I don’t think Netanyahu’s accounting of Sarmiento’s motives holds up under scrutiny. The converso overrepresentation in Juan II’s court and Alvaro de Luna’s support base by his own admission was a very real thing. The nobles were likely just as aware of it as the commoners, if not more so. In the years leading up to the rebellion, Alvaro de Luna and Juan II had been alienating their rivals, perceived or otherwise, by imprisoning them and seizing their assets. It was not the case that aside from Sarmiento and the commoners, all was well and good in Castile.13 It seems rather unlikely that Castilian nobility hadn’t begun to notice any patterns in terms of who was and wasn’t among De Luna’s and Juan II’s support base. Moreover, similar displays of ethnic strife between conversos and old Christians occurred in Ciudad Real a mere 15 days following the outbreak of the Toledan rebellion. “The [converso] tax collector Juan González (later burned by the Inquisition) and three hundred other men of said ancestry armed themselves and took to the streets, threatening to burn down the city before anyone decided to attack them.” This too was all apparently in a “dispute over the possession of the public notaries which it was said were bought by Judaizers and New Christians.”14 Even if Sarmiento orchestrated the rebellion in Toledo, as Netanyahu argues, he didn’t invent the larger ethnic conflict that was brewing in the region, nor did he invent converso overrepresentation in the notaries, which seems to have been ubiquitous throughout the region.

Many modern academics and commentators might argue here that such overrepresentation in the notaries could be attributed to an intelligence advantage rather than an ethnocentric in-group strategy. The evidence at hand, however, doesn’t support such a conclusion. Richard Lynn’s notable book, The Chosen People: A Study of Jewish Intelligence and Achievement, states that the bulk of Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain in 1492 moved to the Balkans, (p. 335) where the Sephardic IQ is currently 98. (p.298) In Lynn’s The Intelligence of Nations, the Spanish national IQ was rated at roughly 94. (p. 145) While statistically significant, a four point difference isn’t very compelling to support the former hypothesis. Moreover, another paper by Lynn, North-South Differences in Spain in IQ,15 reports that the average IQ in Northern Spain is 101 while the average in the South is 96. The average IQ for Catalonia and Valencia in Lynn’s paper was 102.

There is another paper, Numeracy of Religious Minorities in Spain and Portugal in the Inquisition Era, (Juif et al 2019)16 that attempts to compare the numeracy rates of “Jewish-accused” conversos with those of the broader Catholic masses during the Inquisition. The goal was to find evidence of “Jew’s human capital relative to the non-Jewish majority’s.” The study never discusses IQ directly, but it seeks to correlate rates of numeracy with education level which in turn can be correlated with IQ. The study’s finding was that Jewish-accused individuals had higher numeracy rates compared to the broader population, but the study also states that “Catholic priests and other groups of the religious elite who were occasional targets of the Inquisition had a similarly high level of numeracy.” This would suggest that, regardless of ethnicity, there was a high rate of numeracy within the higher socioeconomic rungs of Spanish society. The Inquisition does not appear to have targeted individuals of lower socioeconomic status.

If we consider that, by virtually all accounts, the sephardic Jews were not peasants, but rather a monied class of relative high socio-economic status,17 it may well be that the average converso indeed had a higher IQ than the average old Christian peasant. Even so, there is no evidence that the conversos were significantly more intelligent than the old Christian nobility such that one would expect the conversos to dominate the notaries. People have produced various estimations for the population of each major ethnic bloc in medieval Spain. None of them are particularly convincing, but with that caveat in mind, the total population in 1492 is generally said to have been around three million. The Jews, it is said, were around 300,000. Supposedly, there were half a million Muslims. If those figures are accurate, it would be informative to ascertain how many of the 2.2 million old Christians were of the noble classes. It may be that the old Christian noble classes numerically comprised a similarly small figure relative to the larger population of commoners. In effect, there may have been two relatively small but high socioeconomic rungs of Spanish society roughly of equal intelligence and size in the ‘resource competition theory’ that Kevin MacDonald has forwarded in his book, A People That Shall Dwell Alone. In such a setting, the conversos would be at an advantage only if they had adopted a group strategy against the old Christian nobles who in contrast had remained relatively individualistic until the implementation of Limpieza de Sangre policies.

It also appears to be the case that in none of the contemporary documents that sought to condemn Sarmiento’s rebellion does anyone counter the basic idea that conversos were indeed overrepresented in the manner Sarmiento and others described. Critics simply accused the rebels of having acted without proper cause and justification.

As far as Sarmiento’s motives go, they appear to have gone well beyond personal interests and ambitions. It is far more likely that he was sincerely motivated by a moral and religious conviction—perhaps even an emergent ethnic awareness—to protect his fellow old Christians from what he saw as their abuse and exploitation on the part of a hostile outgroup. If Sarmiento was only interested in political expediency, it was not a wise move for him to take up a stance that burned all possible bridges with the converso power base in such an exceedingly dangerous setting. Once the Toledan rebellion began, Juan II officially revoked and seized Sarmiento’s titles and properties, and sought to bring him and all his supporters to justice. Even Pope Nicholas V condemned the rebellion. He excommunicated Sarmiento along with over 500 others for their actions, and declared the entire city in “entredicho” which essentially barred all its inhabitants from participating in various ecclesiastical affairs.18 He then published the document Humani generis inimicus, (Enemies of the human race) in which, as Benito-Ruano put it, “he affirmed the unity of the Christian flock, regardless of the ancestry of its members in the faith, as well as their equal rights to obtain ecclesiastical and civil jobs or benefices.”19

As remarkable as this opposition to anti-converso sentiments was, plenty of other local nobles supported Sarmiento and the rebels’ cause. Curiously, prince Enrique had not been on good terms with his father, and there is reason to think that he clandestinely supported the rebellion’s anti-converso aims. During the rebellion, the prince was welcomed into the city by the rebels, and he had agreed to all of their demands. None of the rebels would be tried for their crimes, none of the property stolen would be returned to the conversos, and none of the conversos banished from the city would be allowed to return. It does appear that after a series of political intrigues, Enrique may have had a falling out with Sarmiento, but the details that the Crónica de Juan II provides seem strange.

The chronicle tells us20 that in November of 1450, with the rebellion still ongoing, the prince learned and disapproved of certain excesses Sarmiento had been engaged in.21 He left his stronghold in Segovia and made his way to Toledo to remove Sarmiento, whom we are also told was plotting to hand over the city to the king.22 This doesn’t make much sense. The prince had been amenable to Sarmiento’s aims while the king had not. The chronicle also states that the prince didn’t take any action against Sarmiento when he first entered the city. In fact, it expressly states that the prince participated in a series of games for “eight to ten days” before finally getting around to summoning Sarmiento. He then asks Sarmiento to hand over his positions to Don Pedro Giron, the Maestre de Calatrava.23

Supposedly, a few days after this, the bishop of Cuenca spoke to Sarmiento on behalf of the prince. He told Sarmiento that the prince wanted him to leave the city.24 The bishop then gave a scathing critique and condemnation of Sarmiento’s behavior. The chronicle condemned Sarmiento for having rebelled against his king, but Enrique, the king’s own son, was no less guilty of this. The same chronicle discusses how the prince impeded several plots on the part of disillusioned rebels to hand the city back over to his father. Moreover, Enrique did not arrest Sarmiento. Instead he granted Sarmiento safe passage to his power center in Segovia. He even allowed Sarmiento to leave the city with all his possessions and wealth, including what the same chronicle accuses Sarmiento of having plundered from the conversos.

The chronicle has several characters pleading with the prince to stop Sarmiento from leaving Toledo with “mas de treinta cuentos.” This presumably means “more than 30 million maravedis.” While maravedis don’t indicate actual coins here, the amount of money here seems absurd and fantastical. Beyond it being 30 times the original loan that instigated the rebellion, the amount would likely have been so physically large and heavy that Sarmiento could not possibly have carried it out of the city. Even Benzion Netanyahu stated that “this does not seem possible.”25 Assuming Sarmiento had 15 million doblas weighing around four grams each, the treasure would probably have weighed over 130,000 lbs. Technically though, the chronicle tells us that Sarmiento left “without the gold and the silver he had stolen” and instead much of what he carried out of Toledo were tapestries, rugs, fancy underwear, bed spreads, silk fabrics, and fine gems. It doesn’t seem any more likely that Sarmiento carried off the equivalent value of 30 million maravedis in these items.

The text does assert that Sarmiento’s caravan had “close to two hundred” beasts of burden, but even if this is true, that wouldn’t have sufficed. Assuming that each animal weighed around 1000 lbs and could carry 20% of its own weight, the maximum carrying capacity of Sarmiento’s caravan would’ve been about 40,000 lbs. And there is still the consideration that once outside the city, such an amount of wealth would’ve required a small army to defend, which Sarmiento, a minor noble, clearly did not possess. Indeed, after Sarmiento’s caravan leaves Toledo, the chronicle has his servants steal his belongings and abandon him over the course of several days. He is robbed by bandits on the road and the very cities he approaches seeking refuge. Even the king at one point confiscates part of what Sarmiento supposedly stole, when the latter is forced to abandon it at a former residence, and yet curiously the king doesn’t give the property back to its rightful owners.26 The account appears purposefully tailored to vilify Sarmiento in a caricatured fashion. Benzion Netanyahu notes that the dialogue between Sarmiento and the bishop of Cuenca is not present in the Crónica del Halconero; it’s only found in the Crónica de Juan II. He calls the account in the latter chronicle, a “tendentious story, which might have been produced by some admirer of Barrientos (in all likelihood, a converso author)…”27

It’s entirely possible that Sarmiento had aggravated the prince by imprisoning certain noblemen whom the prince felt were honorable, but elements of the chronicle are clearly histrionic in nature. It seems more likely that the prince asked Sarmiento to leave the city after Pope Nicholas’s bull against the rebels had been locally issued. The prince may have been concerned with optics and felt that Sarmiento’s departure would ease tensions.28 Either way, the rebellion continued without Sarmiento’s direct participation for over another year, and when it was over, it had effectively accomplished all that he and his followers had set out to achieve.

On March 21st of 1451, Juan II saw fit to pardon all the Toledan rebels. No one was to be punished for their actions, and even more amazing, none of the property taken from the conversos was to be returned.29 It can be deduced from a letter dated to August 13th, 1451 that Juan II also upheld the rebellion’s measure to remove conversos from public office in Toledo.30 On November 20th of the same year at Juan II’s request, the Pope removed the excommunication status from the city.31 Even Sarmiento was eventually pardoned in 1452, and all his former titles and estates were restored. Although Juan II never allowed him to return to court, Sarmiento became a member of Enrique’s court once he succeeded his father to the throne. Sarmiento died naturally in 1463, probably due to parkinson’s disease, having successfully passed on his mayorazgo to his son.32 Alvaro de Luna on the other hand, following another set of attempts at power grabs, was arrested in 1453 by Enrique who had the former constable convicted for usurping royal functions and subsequently beheaded.33

By 1478 the Inquisition was established in Castille via a papal bull with the goal of combating the Judaizing practices of the conversos. By 1483, it was established in Aragon. The former reluctance on the part of the papacy to engage in prejudicial actions against persons of Jewish ancestry had evaporated. In 1492 at the culmination of the Reconquista, Spain enacted the Edict of Expulsion (Decreto de la Alhambra or Edicto de Granada) which expelled all practicing Jews who refused to convert to Catholicism. Those who rejected conversion were given six months to sell their assets, conclude their affairs, and move abroad.34 Although thousands of Jews left, it’s generally believed that the bulk of them opted to convert, and following the historical pattern since the times of the Visigoths, these conversions were in all likelihood mostly insincere. Many of the new converts continued to practice Judaism in secret and maintain old ethnic ties and allegiances and intermarry among themselves. It was in this setting that Limpieza de Sangre became official state policy in Spain.

Benzion Netanyahu asserted that the Spaniards had adopted “the principle of race to discriminate against all conversos” and asked why the Spaniards being so “constitutionally dedicated to the defense of Christian cult and doctrine [would] adopt a policy so alien…so opposed to its laws, teachings and traditions?”35 Perhaps we can find an ironic answer to this question in chapter four of Kevin MacDonald’s Separation and Its Discontents:

The Inquisition was fundamentally a response to failed attempts to force genetic and group assimilation. The real crime in the eyes of the Iberians was that the Jews who had converted after 1391 were racialists in disguise, and this was the case even if they sincerely believed in Christianity while nevertheless continuing to marry endogamously and to engage in political and economic cooperation within the group. Those who had voluntarily assimilated prior to 1391 were not targets of the Inquisition, since such individuals were implicitly viewed as being free from the crime of racialism. It was not the extent of Jewish ancestry that was a crime, but the intentional involvement in a group evolutionary strategy. In this sense, the Inquisition was profoundly non-racist. Rather, it was concerned with punishing racialism.36

Some of MacDonald’s assertions may appear odd, since the Inquisition later developed an entire racial caste system in the Americas. But the historical evidence strongly indicates that the emergent Spanish attitudes toward conversos were formed in response to ethnocentric converso collectivism against old Christians. It should be considered here that the tendency of Christianity in Spain had been to dissolve older ethnic distinctions. The Visigoths had forbidden intermarriage between themselves and local Hispano Romans until the mid 7th century when Recceswinth dissolved the old law in order to promote cultural unity.37 To be clear, these observations are not intended to imply that the Jews of Spain bore responsibility for the Spaniards’ subsequent implementation of their racial caste system in the Americas. As MacDonald also states in his work, “evolutionary theory must also suppose that these tendencies are in no way exclusive to Judaism…”38 My intent here is to discourage academics and others from viewing the emergence of Limpieza de Sangre policies as the progenitor of modern racism.

Beginning of the Translated Text:

In the very noble and very loyal city of Toledo, five days into the month of June, in the year of the birth of our Savior Jesus Christ, one thousand four hundred and forty nine; on this day, standing present in the house and hall of said city of Toledo, the very honorable and noble gentleman Pedro Sarmiento, repostero mayor39 of our Lord the King and his council, and alcalde de las alzadas40 in said city of Toledo and its realm, boundary, and jurisdiction by way of said Lord King, and [standing present] the judges, sheriffs, knights and squires, commoners and people of said city of Toledo, assembled according to habit and custom, especially to hear, discuss, negotiate and provide in the administration and good governance of said city and in other things pertaining and convenient to the service of our Lord God, of said Lord the King and of the public welfare of said city and its residents and inhabitants, and in the presence of myself, Pasqual Gómez, public scribe in Toledo and scribe of the councils of said city, and [in the presence] of the witnesses listed below, Esteban García de Toledo personally appeared in said council in name, and as the representative that he is, of said judges, sheriffs, knights, squires, commoners and people of said city, whose power of attorney passed before me, the aforementioned scribe. [Esteban García de Toledo] spoke with the gentlemen named above, who well know how on many days and in different councils they had discussed and understood about the universal wellbeing of said city, and of the privileges, exemptions and freedoms given and granted to it by the kings of very glorious memory, progenitors of our Lord the King, and by their highness [said privileges, exemptions and freedoms were] confirmed and sworn.41 Among these [privileges, exemptions and freedoms, Esteban García de Toledo] says there was a privilege given and granted to said city by the Catholic of glorious memory, Don Alfonso, king of Castile and Leon, whereby, among other graces, freedoms, and immunities given and granted by him to said city, following the spirit and letter of the law and the holy decrees, [Don Alfonso] ordered and decreed that no converso with Jewish lineage could hold or keep any office or benefice in said city of Toledo, nor in its land, boundary and jurisdiction, for being suspect in the faith of our Lord and Redeemer Jesus Christ, and for other causes and reasons contained within said privilege.

The aforementioned lords had deliberated a few times on the public notaries of said city, which were and are offices that consist in the service of said Lord King and a great part of the benefit of all public things of said city. They had seen and heard, and it was well known to all, that the majority of said notary positions, said conversos tyrannically held and possessed, as much by the purchase with money as by favors and other clever and deceptive means. This was done in contempt of the royal crown of our Lord the King, of said privileges, exonerations, freedoms and immunities of said city, and of the old Christians proper.42 About all this and other things pertaining to the service of God, of said Lord King, and of the public welfare of said city, [the aforementioned lords] had agreed to make a pronouncement and declaration beyond their mercy to date. Consequently, in name of said city, its commoners and people, and in the best manner [Esteban García de Toledo] was able, and was compelled by law to do so, he requested and did request, he demanded and did demand, that [the aforementioned lords] declare and pronounce on all that they understand to be in service of God our Lord and of said Lord King and of the common interest and advantage of said city.

And promptly the aforementioned Pedro Sarmiento and the aforementioned judges, sheriffs, knights and squires, commoners and people of said city, stated that they had already seen and deliberated about what the aforementioned Esteban García stated, and [that] they had ordered him to see his lawyers, intending to be compliant in the service of God, of said Lord King, and of the public welfare of said city. Consequently, above and beyond everything else declared and pronounced by them in the trial that said city brings against its enemy residents for the offenses and crimes committed and perpetrated by them against the service of God, and of said Lord King, and of the public good of said city, the aforementioned lords agreed to make a certain declaration, and they promptly gave another judgment, and they made me, the aforementioned scribe, read it, the tenor of which, with what happened later, is what follows:

«We, the aforementioned Pedro Sarmiento, repostero mayor of our Lord the King and of his council, and his asistente43 and alcalde mayor de las alzadas of the very noble and very loyal city of Toledo, and the judges, sheriffs, knights, squires, citizens and people of said city of Toledo, named above, pronounce and declare that, inasmuch as it is well known by law both canonical and civil, that conversos of Jewish lineage, for being suspect in the faith of our Lord and Savior Jesus Christ, the faith which they frequently profane by judaizing, may not hold such offices or benefices public or private through which they might inflict shame, damages or abuses on old Christians proper, nor may they qualify as witnesses against them. For this reason, privilege was given to said city and its residents by Don Alfonso of glorious memory, that these conversos not hold nor be able to hold said offices or benefices under pain of severe and grave punishments, and because against a very large part of this city’s conversos, descendants from the lineage of its Jews, it is proven, and it seemed and evidently seems, that they are persons highly suspect in the holy Catholic faith, holding and believing profound errors against the articles of the holy Catholic faith, guarding the rites and rituals of the old law, and saying and affirming that our Savior and Redeemer Jesus Christ is a man belonging to their lineage whom the Christians adore as God. And furthermore, [because] they affirm and say that there is a God and a Goddess44 in heaven. And furthermore, [because] on Holy Thursday, while the holiest oil and chrism are consecrated in the Holy Church of Toledo, and the Body of our Redeemer is placed on the Altar, said conversos slaughter lambs and eat them and make other kinds of burnt offerings and sacrifices judaizing. [This is] according to what is contained at length in the inquiry conducted for this reason by the vicars of said Holy Church of Toledo. By virtue [of its findings], the royal justice, following the letter of the law, proceeded heartedly against some of them, and from there, as the holy decrees have deduced, it turns out that most of said conversos do not think well of the holy Catholic faith. Said inquiry we have included here and ordered it to be placed in the archives of Toledo. Additionally, because beyond what has been said above is well known in this city, and as such we have declared it as fact and well known that said conversos live and act without fear of God. And furthermore they have shown and show themselves to be enemies of said city and its old Christian residents, and that notoriously at their petition, insistence and solicitation, a royal tax was placed on said city by the constable Don Alvaro de Luna45 and his henchmen and allies, our enemies, waging a cruel war of blood and fire, of crop destruction and pillaging, as if we were Moors, enemies of the Christian faith.

Such damages, evils, and wars, the Jews, enemies of our holy Catholic faith, have always caused, manifested, and even implemented since the passion of our Savior Jesus Christ. Even the Jews who lived in this city long ago, according to our ancient chronicles, when it was surrounded by the Moors, our enemies, led by their captain Tariq, after the death of the king Don Rodrigo,46 made a deal and sold said city and its Christians and gave entrance to said Moors. In this deal and contract it was decided that three hundred and six old Christians of the city were to be beheaded, and more than one hundred and six were taken from the cathedral and from the church of Santa Leocadia and carried off as captives and prisoners among whom were men and women, children and adults. Consequently, they have, and they do so every day said conversos, descendants of the Jews, through cunning and deceit, taken and carried off and stolen large and innumerable amounts of maravedis47 and silver from our king the lord and from his rents, rights, and taxes, and they have destroyed and ruined many noblewomen, knights and hidalgos.48 Consequently they have oppressed, destroyed, robbed and ravaged all the most ancient houses and estates of the old Christians of this city and its land and jurisdiction and all the realms of Castile, as is well known and as such we regard it.

Furthermore, during the time that they have held public office in this city, and its management and administration, the greater part of said city’s centers49 have been depopulated and destroyed; said city’s own land and centers [have been] lost and alienated.50 Beyond all this, all the maravedis of said city’s income and property have been consumed in their own interests and properties, in such a manner that all of the country’s wealth and reputation have been consumed and destroyed. They are made lords to destroy the holy Catholic faith and the old Christians who believe in it. In confirmation of this, it is well known to this city and its residents that here a short time ago said conversos rose up, assembled, and armed themselves, and as is public knowledge and well known, they set out with the intention and purpose to destroy all the old Christians and myself, the aforementioned Pedro Sarmiento, first and foremost among them, and to throw us out of said city, and to take it over and deliver it to our enemies. What has been said [here] is public and well known, and as such we hold and regard it, and thereby, pronouncing on this as a notorious case and fact, we find:

«That we must declare and pronounce, establish and order, and we do declare, pronounce, establish and order, that all said conversos, descendants of the perverse lineage of the Jews, to any extent, as much by virtue of canon and civil law that rules against them on the things declared above, as by virtue of the aforementioned privilege given to this city by the aforementioned Lord King of very glorious memory, Don Alfonso of Castile and Leon, progenitor of the King our Lord, and by the other Lord Kings his progenitors, and by their highness, [the aforementioned privilege was] sworn and confirmed, [and] as much by reason of the heresies and other offenses, insults, seditions and crimes committed and perpetrated by them to date, that they are to be regarded, just the law regards them, unable and unworthy to hold any office or benefice, public or private, in said city of Toledo, and in its land, boundary and jurisdiction, with which they can hold lordship over old Christians of the holy Catholic faith of our Lord Jesus Christ or cause them damages and offenses. Additionally they are to be regarded as unable and unworthy to give testimony and faith as public scribes or as witnesses, especially in this city. By this judgment and declaration of ours, following the spirit and letter of the aforementioned privilege, liberties, and immunities of said city, we deprive them, and order them to be deprived, of any offices and benefices that they hold, and have held, in any manner in this city. And inasmuch as it is well known to us, and for such we pronounce it, those who follow are to be especially held and regarded as conversos of Jewish lineage:

López Fernández Cota.—Gonzalo Rodríguez de San Pedro, his nephew.—Juan Núñez, bachelor.—Pero Núñez y Diego Núñez, his brothers.—Juan Núñez, promoter.—Juan López del Arroyo.—Juan González de Illescas.—Pero Ortíz.—Diego Rodríguez el Albo.—Diego Martínez de Herrera.—Juan Fernández Cota.—Diego González Jarada, alcalde.—Pero González, his son, and every one of them.»

«Therefore we declare them to be removed from, and we remove them from, any notaries and other offices that they have and have held in this city and its boundary and jurisdiction, and we dictate to the aforementioned conversos, who live and dwell in it and its land, boundary and jurisdiction, that henceforth they may not testify in or benefit from said offices, especially the aforementioned public notaries and their exemptions, neither publicly nor secretly, neither directly nor indirectly, under pain of death and confiscation of all their goods by the walls of said city and its republic. Furthermore, we find that we must order, and we do order, the public scribes of the number51 of said city, Christians old and proper, to whom it belongs the election of said public notaries, that being vacant said notaries that the aforementioned conversos, descendants of Jewish lineage and breed,52 held and hold among themselves, to choose [new] public scribes of said number in accordance with the privilege and judgment granted to them by the Lord King Don Alfonso, named above, and by customary use, and guarding within said elections the form and the oath that must be made. We order that this judgment and its effect be publicly proclaimed in the usual public squares and markets of this city. And by this judgment and declaration, pronouncing and declaring as in well-known fact, we pronounce, declare, and order it in and by these writings.»

And thus given the aforementioned judgment, and read, in the manner that it is, by myself, the aforementioned scribe, Pasqual Gómez, and by the aforementioned Esteban García, attorney of said city, [who read it] in its name, and by Fernando López de Sahagún, public scribe of Toledo, [who read it] in name of himself and of the other public scribes of said city, [the aforementioned lords] stated: that they requested and did request that I, the aforementioned scribe, give it to them as public testimony as many times as they required for safeguard and conservation for the aforementioned parties and themselves. And I, the aforementioned scribe, by order of said gentlemen named above, gave to the aforementioned public scribes this public instrument, according to and in the manner that passed before me in said city of Toledo, on the day, month, year and place named above.

Furthermore, the aforementioned lords of Toledo stated that they wanted, and they ordered, that this judgment and lawsuit of theirs should have the force of a judgment or declaration, statute, or ordinance, or the best form that would be and is valid, and that it was to be, and that it is, issued in favor of the proper old Christians against the aforementioned conversos, and that it was to be understood, and is understood, that it was to be extended and is extended against the conversos past and present and future; but not in the proceedings and rulings,53 that to date they made into deeds or were presented by witnesses. Those should be valid as much as they legally will have to be and be able to be.

Witnesses who were present to this: Periáñez de Oseguera, knight commander of Toledo, of the Calatrava order, and Sancho de Fuelles, and Per Alvares de la Plata, and Fernán López de Sahagún, public scribes in said city. For this, they were especially summoned and requested.

And I, the aforementioned Pasqual Gómez, public scribe of Toledo, of the number and of the councils of said city, was present with the aforementioned witnesses to what has been declared. And by order of the aforementioned Pedro Sarmiento and said city, and by request and claim of the aforementioned Esteban García, the city’s attorney, I wrote this public instrument, and consequently I made here this seal of mine that is such in testimony of truth.—Pascual Gómez, public scribe.

End of the Translated Text

Endnotes

Higuera, op. cit., lib. 28, cap. y, f. 222v, says that the común suspected Cota to have been the originator of the idea of the loan and that he influenced Alvaro to accept it. See Crónica, año 1449, cap. 2, pp. 661b-662a; Halconero, cap. 372, pp. 511-512

I also do not currently have access to the Crónica del Halconero, but the Crónica del Señor Rey Don Juan II cited states the following:

é porque oviéron sospecha, que un mercader muy rico é honrado vecino de la cibdad de Toledo, que se llamaba Alonso Cota, habia seydo movedor deste enprestido…

Y el primero movedor del escándalo fué un odrero vecino desta cibdad de Toledo , é á su voz é apellido se juntó todo el común : é hallóse escrito en una piedra en letras góticas de gran tiempo, que decia así : Soplara el odrero , y alborotarseha Toledo.

Juan de Mata Carriazo. Refundición del Halconero. Espara-Calpe, S.A. Madrid, 1946. (p.CXCII):

…e como abaxaron a coger dos doblas a gente comun, que no las podian dar, por esta causa se ovo de levantar el comun. E fué causa un odrero, que le pusieron dos doblas; por esto decian: sopló el odrero, e levantóse Toledo.

Cargaron sobre las casas de Alonso Cota y pegáronles fuego, con que por pasar muy adelante se quemó el barrio de la Madalena , morada en gran parte de los mercaderes ricos de la ciudad.

Rabbi Dweck delivered a very emotional sermon in which he strongly denounced the phenomenon of a Jew informing on other Jews, said that he is also a victim in this saga together with Klal Yisroel, and asked for prayers from the entire Jewish community for his terrible suffering.

E desque el Rey, que estaba en Valladolid, supo como aquella hacienda que Pero Sarmiento habia robado en Toledo estaba gran parte della en Gumiel de mercado, embió allá á un Escribano de Cámara que se llamaba Fernán Alonso de Toledo, para que todo lo tomase por ante Escribano, é lo truxese al Rey, lo qual así se hizo.

It shall be as Lawful for a Roman Woman to Marry a Goth, as for a Gothic Woman to Marry a Roman. The zealous care of the prince is recognized, when, for the sake of future utility, the benefit of the people is provided for; and it should be a source of no little congratulation, if the ancient law, which sought improperly to prevent the marriage of persons equal in dignity and lineage, should be abrogated. For this reason, we hereby sanction a better law; and, declaring the ancient one to be void, we decree that if any Goth wishes to marry a Roman woman, or any Roman a Gothic woman, permission being first requested, they shall be permitted to marry. And any freeman shall have the right to marry any free woman; permission of the Council and of her family having been previously obtained.

Tomado del árabe andalusí alqádi, ‘juez’, derivado del verbo qádà, ‘juzgar’. Nebrija (Lex1, 1492): Praetor primus. el alcalde dela alçada. Praetro. oris. por alcalde o corregidor. Propraetor. oris. alcalde extraordinario. Rudis rudis. por la vara del alcalde. Uindicta. ae. por la vara del alcalde.

Del latín LEGITIMUM, ‘legítimo, conforme a la ley’, derivado de LEX, ‘ley’.

Nebrija (Lex1, 1492): *Legitimus .a .um. por cosa de lei.

Nebrija (Voc1, ca. 1495 y Voc2, 1513): Linda cosa. nitidus .a .um. elegans .tis.

[A] council officer who could only exercise his office in the town or district to which he was assigned. They are called ‘of the number’ because generally in each locality or district there was a certain number of them, which could not be exceeded.

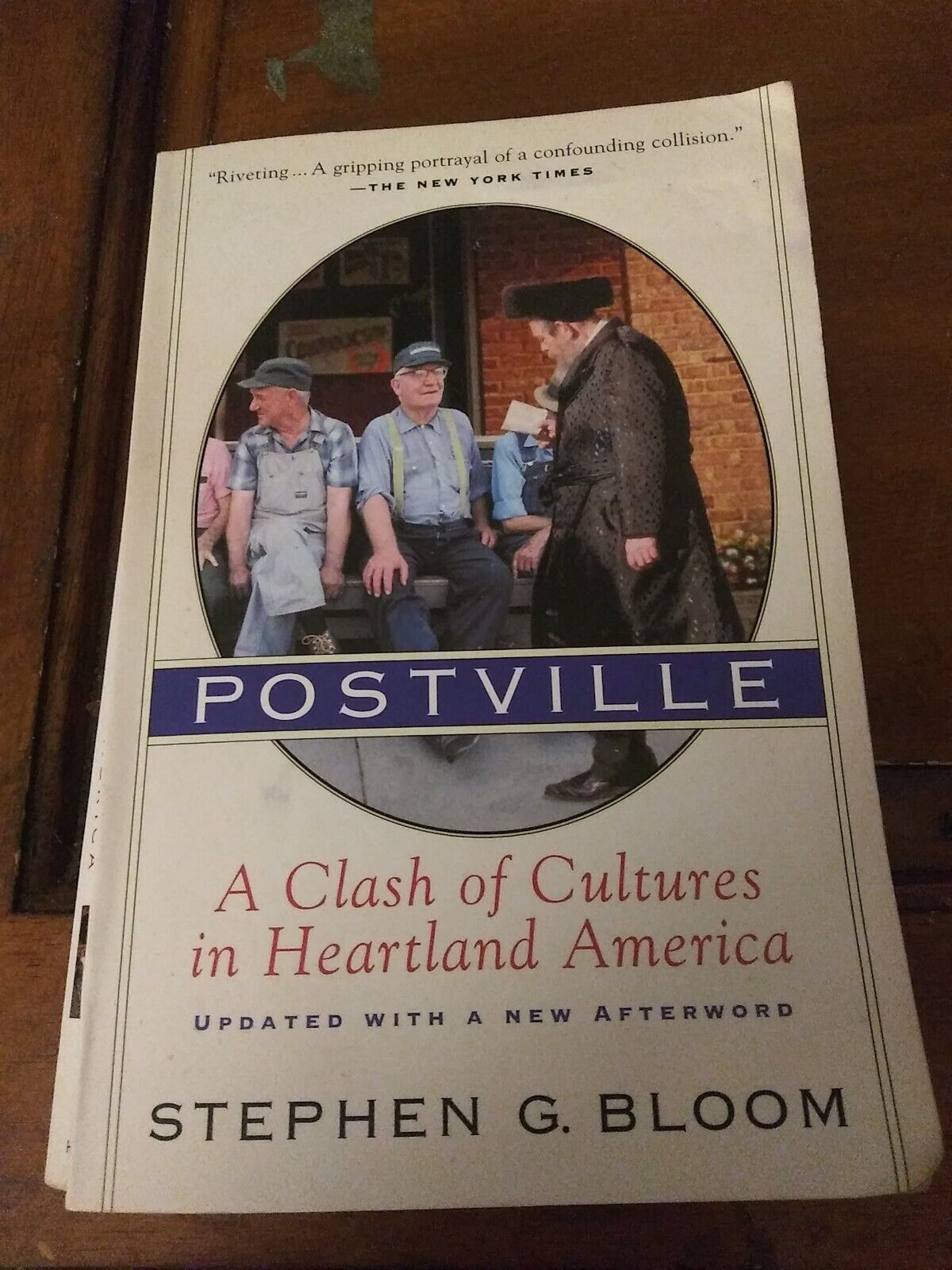

[W]hat the Postville Hasidim ultimately offered me was a glimpse at the dark side of my own faith, a look at Jewish extremists whose behavior not only made the Postville locals wince, but made me wince.

Stephen Bloom

Postville: A Clash of Cultures in Heartland America

Stephen G. Bloom

Mariner Books, 2001 (originally published by Harcourt in 2000)

7367 words

* * *

Did Stephen Bloom write a book that savaged the Jews?