Religion, Race, and Ethnicity in Greco-Roman Antiquity New Perspectives on The Lordship of Jesus, Judaism, and the “Truthiness” of Christianity, Part Two

What Do We Know About Jesus and His Movement?

For Christians such as Stephen Wolfe, the declaration that “Jesus is Lord” signifies that Jesus is God. It is, however, not at all obvious that the historical Jesus considered himself to be a divine being, on a par with the ruler of all creation, the Lord of lords and King of kings. Nor did his disciples. James Dunn contends, however, that the “earliest forms of the Jesus tradition were the inevitable expression of their faith in Jesus.” The first forms of that disciple faith were not yet the “Easter faith, not yet of the gospel as it came to be expounded by Paul and the other first apostles.” They were nonetheless “born of, imbued with, expressive of [a] faith” produced by “the impact Jesus had made severally upon them.” Dunn insists that there is no point in scholarly efforts to distinguish the “historical Jesus” from the Christ of faith. There is only one Jesus available to us; namely, “Jesus as he was seen and heard by those who first formulated the traditions we have.” According to him, “we really do not have any other sources that provide an alternative view of Jesus or that command the same respect as the Synoptic Gospels in providing testimony of the initial impact made by Jesus.”[I]

But, of course, the earliest written versions of the pre- and post-Easter disciple faith did not appear until twenty or so years after the death and reported resurrection of Jesus. Dunn appeals to a process of oral transmission to bridge the gap between the death of Jesus in 30 AD and the earliest manifestation of a written tradition of faith in the Lordship of Jesus Christ. He assumes that “the great majority of Jesus’ first disciples would have been functionally illiterate.” So, too, would most of the earliest followers of the Jesus movement. Accordingly, we cannot assume that Jesus himself was literate. That being so, “it remains “overwhelmingly probable that the earliest transmission of the Jesus tradition was by word of mouth.” Inevitably, therefore, oral faith tradition was a group tradition “used by the first churches and [was] presumably at least in some degree formative of their beliefs and identity.” [II]

Having grown accustomed to the written forms of the Jesus tradition, we naturally prefer such literary explanations. While Dunn presents a case for confidence in the oral histories lying behind the written gospels, he acknowledges the “brutal fact…that we simply cannot escape from a presumption of orality for the first stage of the transmission of the Jesus tradition.” As a “living tradition” of oral performances, the early Jesus tradition must have been both stable and variable, fixed and flexible. Dunn maintains, however, that the variability of the oral tradition “is not a sign of degeneration or corruption. Rather, it puts us in touch with the tradition in its living character, as it was heard in the earliest Christian groups and churches, and can still be heard and responded to today.”[iii]

Dunn’s thesis begs at least two important questions. One such issue, whether the earliest ekklesia of the Jesus movement can properly be described as “Christian,” will be dealt with below. The other is whether the gospels really were histories or biographies. In other words, did they transmit a true and historical witness to the characteristic features of the Jesus tradition, thereby reflecting “the original impact made by Jesus’ teaching and actions on several at least of his first disciples?”[iv] On this issue, Dunn reflects the conventional approach to the Synoptic gospels. Ever since the nineteenth century, most scholars have characterized the gospel authors as literate spokespersons for their religious communities.

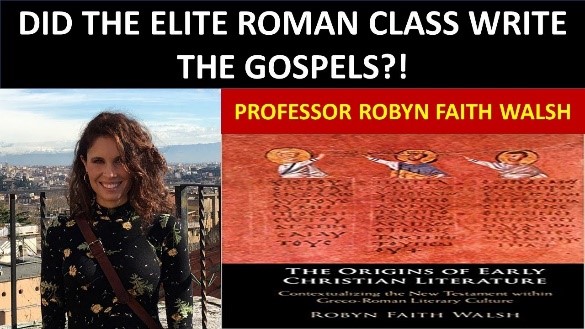

Robyn Faith Walsh, however, doubts that the gospel writers were engaged in “documenting intragroup ‘oral traditions’ or preserving the collective perspectives of their fellow Christ-followers (e.g., the Markan, Matthean, or Lukan ‘churches’).” Instead, she argues, “that the Synoptic gospels were written by elite cultural producers working within a dynamic cadre of literate specialists—including persons who may or may not have had an understanding of being ‘in Christ’.” Her recent work on early Christian literature compares “a range of ancient bioi (lives), histories, and novels” to the gospels, concluding that the latter works “are creative literature produced by educated elites interested in Judean teachings, practices, and paradoxographical subjects in the aftermath of the Jewish War” (66–73 AD).[v]

Walsh contends that the gospel writers were not “strictly concerned…with writing histories.” Nor, however, should their works be treated “principally as religious texts.” New Testament scholars, she believes, “muddle” the social context in which the gospel writers worked by presuming antecedent “oral traditions, Christian communities, and their literate spokesmen.” Like Dunn, they “continually look for evidence of socially marginal, preliterate Christian groups…treating the gospel writers not as rational actors but as something more akin to Romantic Poets speaking for their Volk.”[vi]

In contrast, Walsh approaches the gospels as a classical scholar “would any other kind of Greco-Roman literature.” She observes that “Greek and Roman authors routinely describe themselves writing within (and for) literary networks of fellow writers—a competitive field of educated peers and associated literate specialists who engaged in discussion, interpretation, and the circulation of their works.” Given “such a historical context, the gospel writers are not the ‘founding fathers’ of a religious tradition.” Rather, they are better understood as “rational agents producing literature about a Judean teacher, son of God, and wonder-worker named Jesus.” The gospels, therefore, “represent the strategic choices of educated Greco-Roman writers working within a circumscribed field of literary production.”[vii]

Walsh calls into question Christianity’s own myth of origins, treating it as an example of the “invention of tradition.”[viii] Unlike Dunn, she rejects the “limiting perspective that accepts the first-century Jesus movement as a recognizable and coherent social formation.” It is only the “uncritical acceptance of Christianity’s myth of origins” that authorizes the assumption that “Christianity” emerged in the first century as a “spontaneous, cohesive, diverse, and multiple” movement. She does acknowledge that “it is possible that the authors of the Synoptic gospels were associated in some measure with a group of persons either interested in or actively participating in practices pertaining to the Jesus or Christ movement.” But, “ultimately,” she says, that “remains conjecture.”[ix]

Speaking of conjecture, it is significant that Walsh blithely asserts that the Synoptic gospels were produced in the “aftermath of the Jewish War” while, in the next paragraph, remarking that her study does “not scrutinize dates for these writings.”[x] The cognitive dissonance created by the juxtaposition of those two statements immediately called to my mind the vivid impression left by the professor in my first-year honours history class as he repeatedly and forcefully emphasized the importance of accuracy in the dating of historical documents and events. This is a perennial issue in New Testament scholarship. Despite the existence of several solid studies dating, not just the Synoptic gospels, but the New Testament, as a whole, to the period prior to the destruction of the Jerusalem Temple in AD 70, it is commonplace for scholars to assign later dates to the book or books under discussion.[xi] Studies of the Book of Revelation are particularly prone to this practice since a post-70 date allows scholars to ignore the destruction of Jerusalem and instead to treat the book as a prophecy of the doom awaiting the Roman empire, the papacy, or modern-day America. Agnostics and atheists who, by definition, deny the credibility of biblical prophecies of a providential divine judgement on Old Covenant Israel also have an obvious incentive to assume late dates for the New Testament writings as do theologians committed to a futurist eschatology.

Walsh clearly prefers a late date for the Synoptic gospels. On her account, their authors were independent of oral tradition, producing creative literature by employing the conventional tools of their trade. The stories they crafted were “beholden to the dictates of genre, citation, and allusion” arising from within a circle of peers. No mere reflection of oral tradition, their literary choices presented “an idealized view of Jesus and his life using details more strategic than historical.” Consequently, their work now presents scholars seeking to reconstruct the past based on such creative literary artefacts with a problem: “how can we meaningfully distinguish between fiction and history?” But is it necessary to choose between “oral tradition” emanating from functionally illiterate, religious “communities” and the “creative literature” produced by gospel authors who “were similarly trained and positioned, working within cadres of fellow, cultural elites?”[xii]

Walsh doubts that whatever faith might have been engendered by Jesus among his disciples and those who heard their stories was sufficiently powerful to inspire a spontaneous, cohesive, and autonomous ethnoreligious movement operating in his name before the Jewish War. Given such skepticism, Walsh’s assumption of a late date for the gospels makes sense. By the late first century, if Hellenistic writers had little more than Paul’s letters to work with, they clearly would have been on their own in fleshing out the story of a Judean Christ.

But there is a strong case for an early date for each of the Synoptic gospels. Moreover, something like Walsh’s literary community of educated Hellenized Jews was certainly present in both Judea and the diaspora well before AD 70. Members of a Hellenistic Jewish intelligentsia already steeped in the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Bible must have been influenced by a widespread sense of impending d oom spreading among first-century Jews of all social classes. Writers steeped in such an apocalyptic interpretation of restoration theology would have been well-placed to serve as “organic intellectuals” and publicists for the embryonic Jesus movement in major urban centres throughout the empire.[xiii] Such an ethnoreligious movement had little need for well-researched and fully documented biographies of the historical Jesus. Instead, the authors of the Synoptic gospels competed with other writers (and each other) to generate idealized mythic portrayals of a god-like messiah come to usher in the kingdom of God.

oom spreading among first-century Jews of all social classes. Writers steeped in such an apocalyptic interpretation of restoration theology would have been well-placed to serve as “organic intellectuals” and publicists for the embryonic Jesus movement in major urban centres throughout the empire.[xiii] Such an ethnoreligious movement had little need for well-researched and fully documented biographies of the historical Jesus. Instead, the authors of the Synoptic gospels competed with other writers (and each other) to generate idealized mythic portrayals of a god-like messiah come to usher in the kingdom of God.

Jesus as Lord

In Mark, the shortest and probably the first of the Synoptic gospels, the very first verse identifies Jesus as the Son of God. For Christians, ever since the Council of Nicaea in the early fourth century, “Son of God has been the key title for Christ.” As such, it “has all the overtones of the full-blown Trinitarian formula— ‘Son of God’ means second person of the Trinity, ‘true God from true God, begotten not made,’ etc.” But, as James Dunn points out, this was not the case in Jesus’ lifetime. In the Hebrew Bible “it could be used collectively of Israel…or in the plural in reference to angels, the heavenly council…or in the singular of the king.” Indeed, more generally still, the title could be used to characterize anyone “who was thought to be commissioned by God or highly favoured by God.” Even in relation to Jesus, “initially at least, ‘son of God’ did not necessarily imply any overtones of divinity.”[xiv] In time, of course, the title, as applied to Jesus, did suggest that he was divine in some sense. But, even though first-century Jews “believed that there was only one God Almighty,” as Bart Ehrman reminds us, “it was widely held that there were other divine beings—angels, cherubim, seraphim, principalities, powers, hypostases.” Moreover, there was no impassable gulf between the human and the divine. “Angels were divine, and could be worshipped, but they could also come in human guise.” Conversely, it was possible for humans to become angels or demi-gods.[xv]

What about Jesus? In all three Synoptic gospels, when (1) Jesus is baptized by John; (2) the heavens were torn asunder; (3) a voice from heaven was heard; (4) the voice declared Jesus to be his Son; and (5) the Spirit descended. Similarly, the temptation narratives which follow agree that (1) the Spirit led Jesus into the wilderness; (2) Jesus’ sojourn there lasted forty days; and (3) he was tempted by Satan. Whether Matthew and Luke predate the gospel of Mark or expand upon it, their temptation stories provide essential insight into how Satan tempted Jesus in the desert. They reveal the psychic fault line within Jesus’ messianic consciousness. The Son of God is bound by filial loyalty to the Father; yet Jesus is also by right the uncrowned king of the Jews, and presumably of a restored Israel as well. Hence, he is bound by religious obligations rooted in blood, law, and tradition to share and respect the worldly ambitions of his tribe and people. In Mark’s mythic image of Paradise Restored, Jesus remains curiously passive while Satan actively works his wiles. By contrast, in Matthew and Luke, Jesus resolutely resists three powerful temptations.[xvi]

Knowing that Jesus has fasted for forty days and nights and is bound to be famished, Satan challenges him to demonstrate that he really is the Son of God by commanding that the stones at his feet be made bread (Matt. 4:2). Satan’s first temptation calls to mind John the Baptist’s rebuke to the Pharisees and Sadducees several verses earlier in the text. There, John warns them “not to say within yourselves, We  have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham (Matt. 3:9). John expects the carnal pride displayed by these representatives of the Jewish religious establishment to be followed by a fall. Anticipating Paul’s mission to the Gentiles (Rom. 11:11), John is certain that the ethnoreligious movement soon to be launched by Jesus will produce so many children of Abraham (according to the spirit) that Abraham’s seed (according to the flesh) will be provoked to jealousy. In effect, when tempting Jesus to flaunt his miraculous powers as the Son of God, Satan serves as a stand-in for the Pharisees and Sadducees.

have Abraham to our father: for I say unto you, that God is able of these stones to raise up children unto Abraham (Matt. 3:9). John expects the carnal pride displayed by these representatives of the Jewish religious establishment to be followed by a fall. Anticipating Paul’s mission to the Gentiles (Rom. 11:11), John is certain that the ethnoreligious movement soon to be launched by Jesus will produce so many children of Abraham (according to the spirit) that Abraham’s seed (according to the flesh) will be provoked to jealousy. In effect, when tempting Jesus to flaunt his miraculous powers as the Son of God, Satan serves as a stand-in for the Pharisees and Sadducees.

Having failed in his first attempt, the tempter holds out another enticement calculated to fire the imagination of first-century Jewish Zealots keen to restore Israel to her former imperial glory. Satan takes Jesus to the top of the highest mountain, pitching the prospect of dominion over all the kingdoms of the world if only he will “fall down and worship me (Matt. 4:9; Lk. 4:7). Jesus rejects this temptation as well. Nor is he moved to weaken his determination not to tempt God when Satan sets him upon a pinnacle of the Jerusalem temple, inviting Jesus to prove that he is the Son of God by jumping off the edge, trusting in angels to save him from certain death (Matt. 4:5-7; Lk 4:9-12).

Matthew 4:1-11 and Luke 4:1-13 help us to see that Satan’s three temptations reflect the irrepressible conflict between the two personae incarnate in Jesus’ messianic consciousness, the exalted Son of God, and the historical king of the Jews. During those forty days in the desert, Jesus struggled to reconcile those potentially contradictory roles. In both gospel narratives, Jesus resolves his messianic identity crisis. In doing so, he learns how to preach the Word to his people—the lost sheep of Israel (Matt. 10:6)—in accordance with the will of the Father. He also learns that Satan will dog his footsteps to the cross and beyond. Clearly, the temptation narratives in the Synoptic gospels encapsulate the world-historical conflict between the spiritual Israel of God and Old Covenant Israel according to the flesh. In fact, the seismic shift in the foundations of the cosmic temple during the first century drove the entire cast of characters in the gospels towards the creation of a new heaven and a new earth.[xvii]

It is a mistake to read the temptation stories as an account of the sort of existential crisis that might face any human being in any time and any place.[xviii] Jesus faced those temptations, not because he was a human being but as a remarkably gifted and devout Jewish holy man descended through the royal line of David from the seed of Abraham. Scot McKnight demonstrates that “Jesus’ God is the national God of Israel, not some abstract universal deity. He is the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob; he is the God of David and of the prophet; he is the God of the Maccabees and of John the Baptist.” Jesus’ vision of the kingdom of God was animated not “by an abstract religious feeling but [by] a concrete realistic vision for God’s chosen nation.” It “concerned Israel as a nation and not a new religion”. Accordingly, “[w]hen Jesus taught his disciples to pray for the kingdom to come (Matt 6:10), he surely had in mind more than an existential encounter with the living God that would give his followers an authentic experience”. For McKnight, it follows that “[t]he most important context in which modern interpreters should situate Jesus is that of ancient Jewish nationalism.”[xix]

Both John and Jesus “had one vision for their contemporary Israel, and that was for Israel to become what God had called it to be.”[xx] For Jesus, God was not a universal deity. Israel stood in a covenantal relationship with the Father known to no other nation. Throughout the narrative of the Hebrew Scriptures, “God never destroys his offspring…but rather pursues them in order to bring them to perfection.”[xxi] The telos of that covenantal history was to be perfected in the Lord Jesus and the righteous remnant of Old Covenant Israel; they alone were the true Israelites, forever separated from the false Israelites when the nation faced its final judgement (Matt 13:41-43). Jesus’ messianic mission was “to lead Israel away from a national disaster and towards a redemption that would bring about the glorious kingdom.” From the time of his confrontation with Satan in the wilderness it became clear to him that he would have “to offer himself consciously and intentionally to God as a vicarious sacrifice for Israel in order to avert the national disaster.”[xxii]

But there was more than one vision of Israel’s destiny in the popular imagination of first-century Judaism. Steeped in a tradition of chauvinistic religious rhetoric dating back to the Maccabean revolt in the second century BC, most first-century Judeans scoffed at the notion that “true Israelites” were not “destined to be part of God’s eschatological people…on the basis of heredity.” They rejected the charge made by John the Baptist and Jesus that Israel according to the flesh had “forfeited their enjoyment of covenant blessings and was in exile “because of unfaithfulness and sinfulness.” Certainly, they did not believe that “God was forming a new people” based solely on repentance, righteous obedience, and covenant faithfulness.”[xxiii]

Most first-century Jews were confident that the God of Israel would rest forever in a temple made by hands in Jerusalem. Few took seriously Jesus’ warning that in their lifetime a newly inaugurated kingdom of God would pronounce final judgement on Old Covenant Israel and throw the “false Israelites” into the flames of hell. (Matthew 13:40-43). Jesus knew his fellow Jews longed instead for the restoration of national Israel according to the flesh. Indeed, inspired as he was by his own national vision for Israel, he shared the messianic longing resonating within the blood faith of his people. In his heart of hearts, Jesus could not properly deny the satanic spirit of the Maccabees and the zealots a fair hearing.[xxiv] Indeed, Jesus saw that spirit at work even in his disciples, most notably on the occasion in Mark 8:31–33 when he administered the sternest possible rebuke to Peter: “Get thee behind me, Satan; for thou savourest not the things that be of God, but the things that be of men.”[xxv]

To put the matter plainly, it was not his generic humanity tempting Jesus with bread, universal dominion, and independence from the Father. Rather, it was his inner Jew. The historical Satan emerged within the breast of the historical Jesus Christ. As a charismatic personality, at ease in crowds, recognized in childhood as the king of the Jews, and by the Father as his Son, Jesus could hardly fail to empathize with all but the most grandiose aspirations of his own once-holy people.

Did Jesus Think He Was God?

In the New Testament, Jesus is often given the title “Christ,” a Greek translation of the Hebrew word for messiah, meaning “one who is anointed.” As with a “Son of God,” to be anointed was to be “chosen and specially honoured by God…in order to fulfill God’s purposes and mediate his will on earth.” Both titles could be “used to refer not to a divine angelic being, but to a human being.” Some Jews “deeply committed to the ritual laws given in the Torah” had the idea that the messiah would appear as a great and powerful priest who would serve as a future ruler of Israel, interpreting and enforcing the law of God. More commonly, first-century Jews looked forward to the appearance of a messiah as a mighty warrior who would overthrow the oppressors who had taken over the promised land, thereby restoring both the Davidic monarchy and the nation of Israel. Others held to a more apocalyptic vision in which the coming of the messiah would bring a new creation, not just a political revolution, but “the Kingdom of God, a utopian state in which there would be no evil, pain, or suffering of any kind.”[xxvi]

According to Bart Ehrman, it seems likely “that Jesus’s followers, during his lifetime, believed that he might be this coming anointed one.” But they certainly did not expect him to die and rise from the dead. Nor did Jesus. But he did think of himself as the messiah. He did expect to become the king of Israel, not by means of political struggle or military victory, but when God intervened in history to destroy the forces of evil and to make Israel a kingdom once again ruled through his messiah. He prophesied, publicly and privately, that the kingdom would arrive when the Son of Man came in judgement against everyone, and everything opposed to God. In fact, Ehrman observes, “Jesus told his disciples—Judas Iscariot included—that they would be seated on twelve thrones ruling the twelve tribes of Israel in the future kingdom.” Ehrman is convinced that “Jesus must have thought that he would be the king of the kingdom of God soon to be brought by the Son of Man.” Everyone knew that the future king of Israel would be the anointed of God, the Messiah. “It is in this sense that Jesus must have taught his disciples that he was the messiah.”[xxvii]

Both Jesus and his disciples expected that the messiah was destined to defeat the enemy; instead, the putative messiah was “arrested, tortured, and crucified, the most painful and publicly humiliating form of death known to the Romans.” Such an outcome “was just the opposite of what Jews expected a messiah to be.” But then “they came to believe that Jesus had been raised from the dead, and this reconfirmed what had earlier been disconfirmed.” Their faith was restored: “He really is the messiah. But not in the way we thought!”[xxviii]

Dr. Bart Ehrman

Ehrman hastens to add that, while the historical Jesus did think of himself as “a prophet predicting the end of the current evil age and the future king of Israel in the age to come,” he never—not in the Synoptic gospels at least—called himself God. Of course, in the gospel of John, “Jesus does make remarkable claims about himself.” For example, in John 8:58, “Jesus appears to be claiming not only to have existed before Abraham, but to have been given the name of God himself.” Ehrman argues that not only was the gospel of John produced later than the Synoptics, but verses, such as Jesus’ proclamation that “I and the Father are one” (John 10:30), “simply cannot be ascribed to the historical Jesus.” Instead, Ehrman tells us, “What we can know with relative certainty about Jesus in that his public ministry and proclamation were not focused on his divinity; in fact, they were not about his divinity at all.” Rather, they were about what “the kingdom that God was going to bring. And about the Son of Man who was soon to bring judgement upon the earth.”[xxix]

But, if the historical Jesus never claimed to be God, how did this messianic Judean prophet become a Hellenized cosmic Christ? That story, Ehrman explains, begins with the crucifixion and death of Jesus. “It was only afterward, once the disciples believed that their crucified master had been raised from the dead, that they began to think that he must, in some sense, be God.”[xxx] Before his death, the followers of Jesus believed that he was the messiah, the king of the future kingdom. After the discovery of the empty tomb, they were convinced that he had been exalted to the heavenly realm. It was then that they knew he was the future king and fully expected him to come from heaven to reign as the Son of Man. In his role as the Son of Man, Jesus would have been understood to be a divine figure. Indeed, in one sense or other, in all four of his exalted roles—as messiah, as Son of God, as Son of Man, and as Lord—Jesus was divine. But, in no sense did his followers understand Jesus to be God the Father. Ehrman emphasizes that:

whenever someone claims that Jesus is God, it is important to ask: God in what sense? It took a long time indeed for Jesus to be God in the complete, full, and perfect sense, the second member of the Trinity, equal with God from eternity, and “of the same essence” as the Father.[xxxi]

How Did Jesus Become God?

Even if Jesus did not become fully God until the fourth century, his divine status was assured at the resurrection. As a historian, however, Ehrman does not think “we can show—historically—that Jesus was in fact raised from the dead.” When “it comes to miracles such as the resurrection,” he declares, “historical sciences simply are of no help in establishing exactly what happened.” In other words, Ehrman is not saying “that the resurrection is what made Jesus God.” Rather, “it was the belief in the resurrection that led some of his followers to claim he was God.” In short, Ehrman denies the historicity of the resurrection. As far as he is concerned it never happened. As for the empty tomb, it too is no more than legend. Victims of crucifixion were not given proper burials. Indeed, he claims there is good reason to accept “the rather infamous suggestion,” made by John Dominic Crossman, “that Jesus’s body was not raised from the dead but was eaten by dogs.”[xxxii]

Other historians make the similarly unorthodox suggestion that the facticity of the empty tomb and resurrection narrative may not have mattered, as such, to those who constructed it. Richard C. Miller, for example, contends that the gospel resurrection narratives were never intended to demonstrate historical truth through research and evidence. Sometime around 150 AD Justin Martyr admitted as much in his 1 Apology. As summarized by Miller, the burden of Justin’s Christian apologia was as follows: “We, O Romans, have produced myths and fables with our Jesus as you have done with your own heroes and emperors; so why are you killing us?” This appears to be an admission “that the earliest Christians had composed Jesus’ divine birth, dramatically tragic death, resurrection, and ascension within the earliest Christian Gospel tradition as fictive embellishments following the stock structural conventions of Greek and Roman mythology.”[xxxiii] In other words, the gospel accounts of the risen Jesus differ in detail but not in kind from fables surrounding antique Mediterranean demigods such as Hermes, Dionysus, and Heracles, as well as emperors such as Caesar Augustus.

Indeed, Miller observes, Justin’s argument does “not even qualify as an ‘admission’ per se but merely arose as a statement in passing, as though commonly acknowledged both within and without Christian society.” Justin’s point, however, was not just that there was “nothing unique” or sui generis about the “dominant framing contours of the Jesus narrative.” His apology also “asserted that the classical pantheon was, in truth, a cast of demons.” Nor was this assertion the product of a reasoned line of argument. Rather, Justin flatly declared “that the gods were to be understood as wicked and impious. Only out of ignorance did the classical world regard such demons as deities.” It might seem that the Greeks were saying the same things as the Christians but, Justin affirms, the Greek legends “arose by the inspiration of ‘evil demons’ through the ‘myth-making of the poets’” By contrast, Justin simply pronounces the Christian narratives to be “true” without providing any further evidence or reasoned argument to support his claim.[xxxiv]

This was a rhetorical rather than philosophical or historical strategy. Justin was attempting “to assign archaic precedence to Judeo-Christian tradition.” He simply proposed “that demons inspired the classical writers to produce lies or fictions that proleptically mimicked the Christian Gospel narratives.” Miller suggests that Justin’s apology marked a step beyond the task facing the gospel writers in the first century. That is to say that, at first, the gospel “stories succeeded inasmuch as they were capable of appropriating, riffing on, and engaging the conventions of the classical literary tradition” in ways which appealed to an audience comprising both Hellenistic Jews and Gentile God-fearers in diaspora synagogues. By the middle of the second century, however, “early Christians had their sights on a higher prize: a comprehensive cultural revolution of the Hellenistic Roman world.” In this strategic context, it was no longer “enough that Jesus should join the classical array of demigods. … [H]e must obtain a sui generis stature, while condemning all prior Mediterranean iconic figures.” Such ambitions placed new demands on the rhetorical style of Christian apologetics, requiring “an underlying shift in the proposed modality of the Gospel narratives, moving along the continuum from fictive mythography towards historical fact.”[xxxv]

At their appearance in the first century, however, the gospels, the letters of Paul, and the Acts of the Apostles already reflected a “fundamental metanarrative or theme” which amounted to “the systematic abrogation of nearly every isolationist, separatist practice of early Judaism.” According to Miller, “the forms of these urban early Christian constructions were, more often than not, at their core lifted from the structures of classical antique culture, often with a mere outward Judaistic decor.” The resurrection narratives of the New Testament were “first composed, signified, and sacralized in the Hellenistic urban world of Roman Syria, Anatolia, Macedonia, and Greece, these works typically reflected and played on crudely stereotypical myths of Jewish Palestine.” Their syncretic language reflected the adaptation by early Judeo-Christian theology of antique Greco-Roman forms such as “Zeus-Jupiter, with his own storied demigod son born of a mortal woman.”[xxxvi]

So outlined in the neutral scholarly language of “comparative analysis,” it is easy to miss the explosive significance of Miller’s thesis. But, simply by refusing to apply the definite article in reference to the allegedly “unimaginable miracle” which is collectively supposed to be “the singular impetus for the birth of Christianity, Miller challenges the fundamental presuppositions of contemporary Christian apologetics. He denies that one can speak, in the context of Greco-Roman antiquity, of the Resurrection, the Empty Tomb, the Event, the Mystery. He condemns the tacit agreement according to which classicists designate and relinquish to New Testament scholars a uniquely partitioned and sacralized discursive space surrounding “the question of the historicity of Jesus’ narrated resurrection.” His own study identifies “a detailed, shared conventional system between the Gospel resurrection narratives” and what are known to classicists as “the extant translation narratives of Hellenistic and Roman literature.”[xxxvii]

Miller subsumes the “resurrection” language of the Gospels under the broader “translation topos” found in Hellenistic and Roman cultures. He demonstrates how the latter “tradition functioned in an honorific capacity.” In other words, “the convention had become a protocol for honoring numerous heroes, kings, and philosophers, those whose bodies were not recovered at death.” He points to “the translation of Romulus … as the quintessential, archetypical account for a pronounced ‘apotheosis’ tradition in the funerary consecration of the principes Romani.” The Romulus fable relates how the

legendary founding king of Rome, while mustering troops on Campus Martius, was caught up to heaven when clouds suddenly descended and enveloped him. When the clouds had departed, he was seen no more. In the fearsome spectacle, most of his troops had fled, but the remaining nobles instructed the people that Romulus had been translated to the gods. An alternate account arose that perhaps the nobles had slain the king and invented the tale to cover up their treachery. Later, however, Julius Proculus stepped forward to testify before all the people that he had been eyewitness to the translated Romulus, having met him travelling on the Via Appia. Romulus, according to this tale, offered his nation a final great commission and again vanished.[xxxviii]

Miller provides a lengthy catalogue of similar translation fables and contends that such tales “provide a mimetic background for the Gospel narratives.” Like Robyn Faith Walsh, Miller finds that Greek, Roman, and first-century Hellenistic Jewish writers competed, not just with each other, but with older authors such as Homer to mimic, improve upon, and embellish existing examples of the translation topos, or genre. He argues, very persuasively, “that the textualized Romulus indeed figured prominently within early Christian resurrection narrative construction.” He then discusses what such mimetic, rhetorical performances “achieved within the cultural milieu of a Romano-Greek East, that is, in the primitive centuries of the rise of Christianity.” In a distinctly understated fashion, Miller remarks that his “book also tacitly delivers a rather forceful critique of standing theories regarding the likely antecedents of the early Christian ‘resurrection’ accounts.” In particular, he takes careful aim at modern Christian apologetics which deny any antecedents. He attributes such efforts to endow the Resurrection of Jesus Christ with a sui generis status to “a perspective typically arising out of ‘faith-based discourse.’” [xxxix]

Miller “sets forth a more satisfying thesis, a model that more comprehensively explains the available data, namely that such narratives fundamentally relied upon and adapted the broadly applied cultural-linguistic conventions and structures of antique Mediterranean society.” In this cultural context, the early Christian resurrection tale functioned “as an ideology and not as an argued event of history.” Early Christian writers, Miller writes, “did not attempt a case for the historicity of the resurrection of their founding figure.” Instead, Jesus was deployed in the gospel resurrection narratives as “a mythic literary vehicle.” Miller defines “myth” as “a sacred narrative or account” that served to frame the present for the Jesus movement. The resurrection myth functioned, like the Greco-Roman translation fable, “to undo tragic loss, reclaiming the hero in a modal reverie of heroic exaltatio.”[xl]

Miller argues that the innovation of the Gospel postmortem accounts did not reside in the employment of the translation fable convention per se, but in the scandal of the application of the embellishment to a controversial Jewish peasant, an indigent Cynic, otherwise marginal and obscure on the grand stage of classical antiquity.” Jesus emerges as a mythic literary figure in the gospels rather than as a historical actor. As Miller puts it, the risen Jesus became the iconic “image of a counter-cultural ideology” through the conscious appropriation by the gospel writers of the literary protocols of the ancient Hellenistic Roman world.[xli] In accordance with such protocols, Paul and the gospel writers presented Jesus as unique, not because he was exalted as a god following his death, but because he was better than the other gods of the classical world.

[I] James D.G. Dunn, A New Perspective on Jesus: What the Quest for the Historical Jesus Missed (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005), 25, 31.

[II] Ibid., 41, 36, 43.

[iii] Ibid., 53, 125.

[iv] Ibid., 69-70.

[v] Robyn Faith Walsh, The Origins of Early Christian Literature: Contextualizing the New Testament within Greco-Roman Literary Culture (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2021), xiii-xiv.

[vi] Ibid., 3-6.

[vii] Ibid., 5-6.

[viii] Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger, (eds.), The Invention of Tradition (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1984).

[ix] Walsh, Origins of Early Christian Literature, 32-33, 35.

[x] Ibid., xiii-xiv.

[xi] Cf. John A.T. Robinson, Redating the New Testament (Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock, 1976) and Jonathan Bernier, Rethinking the Dates of the New Testament: The Evidence for Early Compostion (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2022).

[xii] Walsh, Origins of Early Christian Literature, 4-6.

[xiii] The term “organic intellectuals” was coined by the Italian Marxist, Antonio Gramsci (1891-1937), but it is not at all anachronistic when transposed into the context of an ethnoreligious movement with geopolitical ambitions in the first century. See, Quintin Hoare and Geoffrey Nowell Smith, (eds. and trans.) Selections from the Prison Notebooks of Antonio Gramsci (New York: International Publishers, 1971), 5-23.

[xiv] Dunn, Partings of the Ways, 170-171.

[xv] Bart D. Ehrman, How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee (New York: Harper One, 2015), 83.

[xvi] Andrew Fraser, Dissident Dispatches: An Alt-Right Guide to Christian Theology (London: Arktos, 2017), 424-446.

[xvii] On the Old Testament account of the creation of the cosmic temple, see John H. Walton, The Lost World of Genesis One: Ancient Cosmology and the Origins Debate (Dover Grove, IL: IVP Academic, 2009).

[xviii] See, e.g., Helmut Thielicke, Between God and Satan: The Temptation of Jesus and the Temptability of Man [orig. ed., 1938] (Farmington Hills, MI: Oil Lamp Books, 2010).

[xix] Scot McKnight, A New Vision for Israel: The Teachings of Jesus in National Context (Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans, 1999), 69, 83, 6, 10.

[xx] Ibid., 6.

[xxi] Anthony D. Baker, Diagonal Advance: Perfection in Christian Theology (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2011), 77.

[xxii] McKnight, New Vision, 147, 13.

[xxiii] Ibid., 62, 110-115.

[xxiv] Ibid., 136-137, 146-147, 96.

[xxv] Mark does not identify Satan’s three temptations in 1:13, but in 14:30 (just before standing trial before the Sanhedrin) Jesus predicts, accurately, that a satanic impulse will cause Peter to “disown me three times” before the cock crows twice. Shortly afterward, the disciples fall asleep three times while on guard duty, revealing the tempter within at work again with a suite of counter-Trinitarian snares likely to entrap Jesus’ closest followers (Mark 14:37-41).

[xxvi] Ehrman, How Jesus Became God, 113-115.

[xxvii] Ibid., 115-119.

[xxviii] Ibid., 116-118.

[xxix] Ibid., 124-128

[xxx] Ibid., 128.

[xxxi] Ibid., 208-209.

[xxxii] Ibid., 132, 157.

[xxxiii] Richard C. Miller, Resurrection and Reception in Early Christianity (New York: Routledge, 2015), 2.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 1-3.

[xxxv] Ibid., 4-5.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 12-13.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 15-16 (emphasis added).

[xxxviii] Ibid., 16.

[xxxix] Ibid., 16.

[xl] Ibid., 16-17, 158, 162.

[xli] Ibid., 180.