The Problematic History of the European Union: Review of ‘Eurowhiteness’

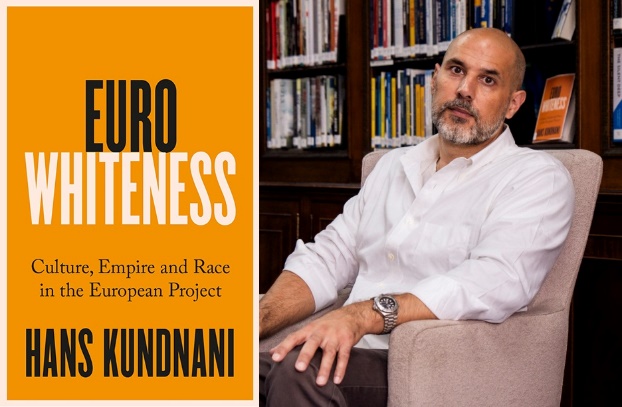

Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project

Hans Kundnani

Hurst Publishers, 2023

Eurowhiteness is one of those books that immediately catches the attention of a “racist”. With a bright orange cover and a title like Eurowhiteness displayed in large block letters, how could it not? Curiosity compelled me to take it down from the bookshop shelf and browse the introductory remarks. After a brief Google search to confirm my suspicions of the mixed-race origins of the author, I was ready to groan and roll my eyes at what I presumed to be a vapid book that deconstructed European identity by arguing that “blackness” or “brownness” somehow has just as much place within Europe as “whiteness.” What emerged from its pages instead was a novel left-wing polemic against the European Union (EU) *because* of its perceived Whiteness.

Author Hans Kundnani was born to an Indian father and a Dutch mother and grew up in the United Kingdom. As with most mixed-race people who struggle to place their identity, he believes this background gives him a unique perspective on European history and identity. His first post-university job was for the Commission for Racial Equality, the enforcement body established by the UK Race Relations Act 1976, and by 2009 he was working for the European Council on Foreign Relations, a think tank dedicated to Pan-European ideas. As Kundnani describes it, Eurowhiteness is the culmination of his shift in thinking from a pro-European convinced of the moral good of the EU, to a critic who has abandoned the myths that once informed his worldview.[1]

Kundnani does not present a bibliography, but his ideological debt to leading thinkers in critical race and post-colonial theory is apparent. His endnotes draw from well-known figures in this sphere such as Charles W. Mills, Gurminder K. Bhambra, Paul Gilroy, and historical forebears Frantz Fanon and W.E.B Du Bois. The acknowledgements section reveals Kundnani’s “particular debt” to Swedish post-colonial scholar Peo Hansen. Hansens’ book Eurafrica, which explores the African strategic fantasies of early Pan-European thinkers — notably Richard von Coudenhove-Kalergi — are what seemingly began Kundnani’s path towards euroscepticism.

Eurowhiteness is well-paced and I can offer no criticism of Kundnani’s cogent writing style. Other reviewers have affixed the word “challenging” to the book, but to those of us not inflicted with colour-blind thinking and who already see the intrinsic link between Western civilisation and the White race, the themes parsed out in Kundnani’s book are hardly cause for discomfort. His claim that the EU has recently taken a “civilisational turn” towards the protection of European identity and that as a result the institution could just as easily be used as a vehicle for racist purposes is also familiar. Way back in 2017 Richard Spencer was pouring cold water on the euphoria over the Brexit vote, arguing that the European Union could instead become a potential racial empire, a counter to NATO and Atlanticism.

The value of this book for readers of The Occidental Observer lies principally in understanding the intellectual journey of the author and discerning the potential for the emergence of a popular left-wing critique of the EU in the Anglosphere and beyond. Kundnani’s transition from EU booster to EU sceptic is instructive, as well as revealing the anti-White perspectives and motivations that can lie behind soft-spoken academics. Despite the myriad of anti-racist measures, tolerance initiatives, and hate speech laws that encompass the modern EU, Kundnani has turned on the European Union because it is just still too White, too Western. After all, the EU’s history is rooted in Europe and much of its historical and present-day motivations are the defence of European people and Western values. That alone is enough to condemn it in Kundnani’s eyes.

Regionalist Racism

Kundnani’s critique of the European Union begins with the dismantling of what he sees is the common misunderstanding of its structural nature. Rather than conceptualising it as an inclusive cosmopolitan project that has renounced nationalism — a position held by both supporters on the left and critics on the right — Kundnani attacks the EU as a project analogous to nationalism. According to Kundnani, it is better understood as a form of “regionalism.” That is, nationalism on a more continental scale, and imbued with all the same chauvinistic impulses, power dynamics and histories of colonial dispossession that nation-states are saddled with.[2] The same impulse towards nation-building is found in the ‘region-building’ of the EU.

Building on this concept of regionalism as nationalism on a larger scale, Kundnani draws upon Jewish academic Hans Kohn’s theory of nationalism. Kohn invented the concept of civic nationalism as distinct from ethnic nationalism ideally suited for facilitating non-White migration. Just as a nation can have strands of civic and ethnic nationalism, so too does the regionalist EU. It possesses both a civic and an ethnic component that waxes and wanes in strength across time; secularism, civil institutions and liberal rights weighed against Christian, illiberal, civilisational and racial ideas. For Kundnani, it is “disturbing” that the EU continues to draw upon such ethnic/cultural elements from Europe’s history.[3]

Chapter 2 briefly traces the history of European identity from its ethnic and cultural origins at the time of the Battle of Tours, where the word was first used by the victorious Franks in order to “other” the external enemy, the Muslims. From the seventeenth century onwards, ideas of Europe began to shift from being strictly synonymous with Christianity. At this point, a rationalist, enlightenment notion of Europe with a civilising mission to the rest of the world emerged, and finally the notion of whiteness or the racial identification of the European peoples as Whites.

Kundnani’s critique of the Enlightenment values that form the basis of the EU follows the now standard deconstruction of its universalism, positing that it is instead of being based in Whiteness and in the particular systems of White supremacy:

… while Enlightenment ideas like the “rights of man” — the antecedent of what we would today call “human rights” — were potentially universal, they emerged from a particular European context, and moreover, were put into practice in a racialized way. … [C]olonialism and slavery were carried out in the name of enlightenment ideas.[4]

The Enlightenment is presented (or problematised, to use the lingo) in the most debased terms possible, as the output of White supremacists. Immanuel Kant, whom Kundnani points out wrote an early appeal for European unity that is now celebrated by the EU, is lambasted for his racial theories. Rousseau is condemned because his writings did not speak directly to the plight of Black slaves in French colonies.

Next, the alleged colonial origins of the EU are fleshed out — the “original sin” of the EU as Kundnani likes to call it. Rather than being anti-colonial, the early movements towards Pan-European unity developed the concept of Eurafrica, which envisioned the African continent as a yet undeveloped source of raw material for a future European power-bloc. Many of the founding states of the EU also held onto their colonial possessions after the formation of the European Economic Community (EEC), the formal precursor to the EU. France and Belgium in particular factored these colonies into their economic considerations for a post-war redevelopment enmeshed into wider Europe. Predatory relations further continued after the formal independence of these colonies, in the form of exploitative labour schemes and guest worker programs.

Kundnani argues that from 1945 onwards, civic regionalism came to dominate as a reaction to the ethnic conflicts of World War II. This was not the clean break from Europe’s past that many claimed it to be, with the older ethnic/cultural regionalist tendencies still pushing through into Pan-European rhetoric. The civilising mission remained, as did the belief in the superiority of European values and the claim of their universality. Even the holocaust is not spared from critique. The EU, Kundnani contends, has used holocaust remembrance as a cover for forgetting colonial injustices, patting themselves on the back for upholding “Never Again” whilst continuing to refuse to engage in decolonisation or recognise Europe’s true original sin. The foundational memory of the holocaust has obscured Europe’s foundational history of colonialism, and thus the EU is a project of political amnesia that has forgotten, or choses to ignore, its origins as a quasi-colonial institution.[5]

The end of the Cold War reignited the civilising mission towards incorporating the EU’s more “backward” eastern Europeans neighbours, those who were European but not quite yet *in* Europe in cultural or political terms. More than halfway through the book, we finally encounter the meaning behind its title, derived from Hungarian sociologist József Böröcz, who proposed a spectrum of Whiteness within Europe. “Eurowhitness” is associated with the centre of Europe in the West and “dirty whiteness”, the less immaculate and somewhat less West European version to the East. Kundnani repurposes the term to refer to the ethnic/cultural version of European regionalist identity. Eurowhiteness, used as a pejorative or a negative by Kundnani, simply means to identify as European in a non-civic (that is, “racist”) way.

With the arrival of the Eurozone crisis in 2010 and the chaos of the refugee influx of 2015, Kundnani argues that the European Union has swung towards a defensive position, focused on countering the external threats to the stability of Europe:

By the beginning of the 2020s, the civic element of European regionalism seemed to have become less influential and the ethnic/cultural element more influential in “pro-European” thinking. In other words, whiteness seemed to be becoming more central to the European project.[6]

Kundnani sees little distinction between pro-European politicians who posit a defence of the “European Way of Life” or who worry about the future of Western civilisation and far right “extremists” who invoke the supposed trope of the great replacement. In the face of these threats to EU stability, those who fear the decline of EU power and sovereignty are the international political equivalents of the those who fear White replacement.[7] After all, both positions are “pro-European.” For Kundnani, the EU’s dramatic response to the war in Ukraine, opening its arms wide for Ukrainian refugees compared to what he sees is the closed-door policy to non-White refugees at its southern borders, is just further proof of the return to Eurowhiteness.

By far the weakest point of the argument is the evidence (or general lack thereof) provided to attribute Eurowhiteness motivations to current EU leaders or bureaucrats. As an outsider, the civic European component still seems predominant and the appeals to European civilisation are mere scraps thrown to a public increasingly disillusioned by the failure of the EU to respond to issues of mass immigration. It feels like a stretch to widely attribute chauvinistic views to the EU leadership, but the impulse to defend Europe as Europe, as some kind of distinct entity of a distinct group of people, does certainly exist enough for the label of Eurowhiteness to stick.

Kundnani believes that a different Europe is needed than the one we currently have.[8] Nearing the conclusion, he briefly hints at the EU itself being a barrier to overcoming Eurowhiteness. He claims that engaging with its colonial past could in fact be a danger to the EU because Eastern European member states with no colonial history or collective guilt over colonialism would resist such initiatives, which could in turn have a disintegrative effect on European identify and the structure of the EU. However, the narrative abruptly ends there and is not further expounded upon, and we are left wondering what his true feelings about the future of the EU are. Kundnani at least admits in the introduction that he is only offering critiques, not solutions — at least not for the EU.

Reconsidering Brexit

The final chapter, Brexit and Imperial Amnesia, changes gears and presents us with a revisionist account of the Brexit Referendum, aimed at the British left still reeling from the 2016 vote. Kundnani challenges the dominant narrative of the Leave vote as a racist vote yearning for a White fortress that shuts the door to migrants. The true nature of the Brexit vote is presented as more complex and less binary, highlighting that one in three members of Britian’s ethnic minority population also voted to leave. Kundnani expands upon the angst of many non-White Britons regarding the EU and their perception that continental Europe is still more racist than the UK. Given the persistence of Eurowhiteness, it remained hard for Britain’s Black and Asian populations to truly feel part of the European project and they have struggled to identify with its history. Kundnani is also captive of these feeling towards the EU, mentioning in the introduction that he could never bring himself to feel “100% European” due to his mixed-race background.[9]

Another area of hostility outlined towards the EU is the discrimination many felt from the changes that entrance into the project brought to immigration. Following the admission of the UK into the EEC, Commonwealth citizens from Britain’s former colonies suddenly found it was harder to enter the UK than continental Europeans. The story is familiar to Australians, who too felt abandoned by the mother country when the border control lines at the airport no longer privileged the peoples of New Brittania.

With the Brexit vote reconceptualised, the Leave decision is transformed into an opportunity, offering the chance for Britain to rebalance its identity. Eurowhiteness and ties to the EU have allowed the UK to escape from its colonial history by focusing on the national identity narratives of Europe and World War II. Through engagement with former colonies, Britain can shift its national story away from Europe. Here, in the final two paragraphs of the book, we finally come to the vehicle of this reimagining of Britain and what perhaps Kundnani sees as the best way to combat Eurowhiteness: immigration policy.

The corrective is a policy which amends the turn away from Commonwealth-based immigration — a form of reparations issued on the path to becoming a less Eurocentric country:

It would be possible to go further in the rebalancing of British immigration policy that has taken place since Brexit — in particular, by making it easier for citizens of Britain’s former colonies to come to the UK. … such a policy — what might be called “post-imperial preference” — could even be thought of as a form of reparations.[10]

Once again, the great replacement trope is an evil conspiracy theory when observed by a critic and an obvious political good when advocated for by a supporter.

Yes. And?

Kundnani’s thesis can be pulled apart on a number of technical levels. The appropriateness of the notion of regionalism as applied to the EU and its analogy to nationalism can be questioned, and in turn there is often a conflation of concepts, with “Europe”, “the European Union” and “EU Member states” used interchangeably as suits his argument. A rather weak critique of neoliberalism also flows underneath the main critique of Eurowhiteness and the linkage between the EU and colonialism feels forced. By the time the EEC came along in the 1950s, European colonialism was in its death throes, far from the height of its power. However, lacking a detailed understanding of the history and functioning of the EU and of the political conceptions of its leadership class, my review of the narrative of Eurowhiteness turns elsewhere.

Much of the book is perplexing if you don’t have a pathological sense of White guilt or an inferiority complex about the success of European civilization. This is without a doubt a book produced from decades spent ensconced in an academic world brimming with anti-White narratives, plundering the rancid depths of post-colonial theory for a vector to attack an institution that even most die-hard progressives support — until they read Kundnani’s book perhaps. The extent of White guilt that a reader must have to agree with his conclusions is altogether frightening when considering that the book has received a generally positive response in the British left-wing press.

To me, the arguments presented in the book elicited a kind of “Yes. And?” reaction, a sense of confusion or bemusement as to why a historical fact or a political reality has been presented as a negative. Kundnani considers it damning evidence of Eurowhiteness that the EU draws upon figures such as Charlemagne and continues to award the Charlemagne Prize in his name. Why is this damning? Because he is European? At its heart, Kundnani’s critique is that the European Union only brings together European nations and peoples, European ideas and values, and strives for European interests and goals. Yes. And? Is this a bad thing? Are Europeans not allowed to do this? The EU was certainly never constituted in any way other than as a continental union, no different than similar unions that now exist in the other regions of the world. The fact that some of the original member states still possessed leftover colonial territories is beside the point.

It is hard to shake the feeling that Kundnani feels there is something inherently dangerous with the European Union setting its geographic limits as Europe and bringing Europeans together. The flat refusal issued to Morocco’s request to join the EEC in 1987 is transformed by Kundnani from an obvious rejection issued to a country trying to simply cash in on proximity to Europe into proof of a malign identity embedded within the EU. Does Kundnani think it was wrong to reject Morrocco’s application? As a country with a long historical link to the African continent, would Spain being rejected from joining the African Union also be couched in such negative framing?

A Union, if you can keep it

Eurowhiteness raises questions regarding the long-term durability of the EU project. If the demographic trends away from a White majority in European nations continue, will we start to see more Euroscepticism from the left, more anti-White reactions against the EU like that which has captivated Kundnani? Whilst it would be comforting to believe that Eurowhiteness is an isolated product of the distinctly British detachment from the EU that has no currency elsewhere, Kundnani draws upon a global range of anti-EU perspectives, both historical and current-day. It’s not hard to see conclusions such as his, presented in an accessible form, from developing in popularity.

Non-whites living in the West have stepped up their rhetoric in recent years, rallying against the presence of White faces and White ideas within their living spaces. Statues have been removed, the Western canon expunged, and names of places and institutions changed for the sake of diversity and anti-racism. Their actions have shown that they believe that all Eurocentric ideas must be challenged, and above all that diverse faces must be predominant in public life. To a degree it is surprising that critiques of the EU along these lines have not emerged before to a significant degree. Perhaps that is simply due to the political left adopting a reflexive pro-EU stance in the face of the right-wing anti-EU stance —a reflexive response that Kundnani is now seeking to correct.

Ultimately, the impulse behind Eurowhiteness is a sense of exclusion by Europe and a feeling of discomfort in Western civilisation, one certainly shared by others of non-European background. Kundnani admits as much himself when he states that: “European identity is externally exclusive — that is, it excludes those who are not European or who cannot think of themselves as being European.[11]” To those of us comfortable with European identity, Charles Martel or Charlemagne are inspirational warriors of our history, men who shaped and fought for the Europe we have and cherish today and without whom we may not even exist.

The Battle of Tours in October 732 — by Charles de Steuben (1788–1856)

All that people like Kundnani seem to see are exclusionary figures who upheld Christendom or who waged wars to defend Europe from dark-skinned Muslims — detestable characters they cannot feel an affinity with and whom they believe only a racist would celebrate. They survey the history of Europe and all the cultural touchpoints behind the EU and find that it just doesn’t represent them. From a racialist perspective, they cannot really be faulted for this. It is a natural impulse to seek out the familiar and to desire to live in an environment that accords with your being and your own racial identity. The problem was always in letting them into the West in the first place.

In all, Kundnani’s polemic against the EU reads as a fear of White unity writ large. Whiteness (or Eurowhiteness) is the threat to overcome. That much is clear when he advocates for non-White immigration as the solution to Britain extracting itself from Eurocentrism and frets about the possibility of the far-right moderating its Euroscepticism and accepting the EU[12].

The center right, it turns out, doesn’t have a problem with the far right. It just has a problem with those who defy E.U. institutions and positions. …

The blurring of boundaries between the center right and the far right is not always as easy to spot as it is in the United States. …

[T]oday’s far right speaks not only on behalf of the nation but also on behalf of Europe. It has a civilizational vision of a white, Christian Europe that is menaced by outsiders, especially Muslims. …

But as the union unites around defending a threatened European civilization and rejecting nonwhite immigration, we need to think again about whether it truly is a force for good.

Any form of White identity, and any association of Whites together as Whites, even if only implicit, must necessarily be a dangerous thing. As Eurowhiteness proves, even Western institutions that we may have once considered safe by virtue of being perceived as progressive are now suspect.

[1] By his own admission this did not however cause him to vote Leave in the Brexit referendum of 2016, presumably because it still felt racist to do so

[2] At this point, Kundnani posits the Marxist theory of nationalism (Hobsbawm, etc.), which claims that national identities only emerged during the Enlightenment era, but it doesn’t impact the argument much.

[3] Kundnani, H 2023, Eurowhiteness: Culture, Empire and Race in the European Project, Hurst & Company, London, 42.

[4] Ibid., p.53—55

[5] For all the complaints about European universality or that “Europe is not the world”, Kundnani conveniently fails to mention the empires and colonial histories of the non-European world, which were every bit as exploitative and arguably more barbaric.

[6] Kundnani, Op. Cit., p.126

[7] Ibid., p.146

[8] Ibid., p.3

[9] Ibid., p.1

[10] Ibid., p.178

[11] Ibid., p.20

[12] Kundnani, H 2023, ‘Europe may be headed for something unthinkable’, New York Times, December 13, retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/12/13/opinion/european-union-far-right.html

His claim that the EU has recently taken a “civilisational turn” towards the protection of European identity and that as a result the institution could just as easily be used as a vehicle for racist purposes is also familiar.

From his book to Brussels’ ear, one can hope. May his fears be realized (or “realised” as they write in his parts).

In the pre-miscegenation era this manfestation would not have had the possibility to exist.

OT https://sharetext.me/7ihtvxjwrq