Jewish–Hungarian Conflicts and Strategies in the Béla Kun Regime, a Review-Essay of “When Israel is King” (Part 4 of 5)

Go to Part 1.

Go to Part 2.

Go to Part 3.

6207 words.

After the elements examined so far, such as networking, press influence, cultural and political movements, and finally the question of the acquisition of power and Jewish activism, it is worthwhile to look more closely at these, in particular, the question of identity, which is a recurrent focus of those who want to dismiss the responsibility of Jewry. According to the narrative, if certain individuals did not declare to the whole world that they were Jewish, they were not Jewish, because according to this infantile logic, it is a matter of choice or proclamation. In reality, identity manifests itself on multiple planes—and then there is also the importance of ethnic traits.

The principle outlined above, however, is not considered by these commentators to be applicable in other cases: for example, if a seemingly White person hits a gypsy, logically one should wait for both persons to declare their identity because it might be that a Hungarian with a gypsy identity hits a gypsy with a Hungarian identity, so to complain about anti-gypsy racism would be premature. Even in the case of the so-called Jewish Holocaust, those who argue in this way accept that the actual, legally protected number of victims, is the real number, regardless of how many of them may not have had a Jewish identity (remember: internationalists can’t be Jews, following a similar logic), showing the highly cynical and biased nature of this tactical nihilism. This postmodern view is thus absurd: while the role of one’s identity is important, there are several aspects to a person’s motivations, inclinations, or needs.

Aspects of the Dynamics of Internationalism and Tribal Networking

We sometimes hear that the Republic of Councils of Hungary (i.e., the Kun regime) was anti-Jewish. In contrast, Jewish ethnic activism was quite free, both in Hungary, and elswhere under early Bolshevism. Although two Jewish leaders in Budapest wanted the Jews to be regarded as Hungarians with Jewish religion by the new Kun regime, other Jews formed a Jewish National Council (Zsidó Nemzeti Tanács), with the permission of the Minister for Nationalities, Oszkár Jászi (1875–1957; Jewish), who “recognized that Jewish national organization was legitimate,” recalls Géza Komoróczy (2012, 354) in his comprehensive work of over 1200 pages, The History of the Jews in Hungary. We also learn that several anti-Jewish events were the result of Jewish infighting, mostly between religious Jews, Zionists, and secular Bolsheviks. Oszkár Jászi, in his emigration to Vienna in 1920, described the Commune as the first revolution in world history in which “Jewry was able to assert itself without any restraint or limit, and thus to freely develop the forces and tendencies that had been dormant within it for centuries” (quoted in ibid., 358).

Jászi described Jewish activism in Russia as an ethnic, tribal movement. According to a lecture given by him to the Galileo Circle on January 28, 1911, the Russians, with their repressive measures, “created the bloodiest, most anarchistic Jewish nationalism … and the result was that this most internationalist people, which did not give much heed to racial and national aspirations, produced bloody nationalist movements” (Jászi, 1982, p.162). Jászi reiterated this on other occasions: the repressive characteristics of the tsarist order “created a suitable soil for the most extreme revolutionary ideas in Jewry. The result of all this was that a hitherto unknown strain of Jewish fanatic nationalism spread throughout the land of Russia” (Jászi, 1912, 139, emphasis in original). He did not specify who or what he meant, but in these years, in addition to the Zionists, the anti-Zionists (who rejected emigration) were openly Jewish and socialist Bundists who later supported the Bolsheviks; moreover, the Bolsheviks themselves were significant (one need only think of their bloody revolutionary attempt of 1905, with Leon Trotsky). In the early 1910s, the Bolshevik movement was already significant, so the adjective “revolutionary” must have been a reference to them and other Marxists. As Gerald D. Surh (2023) summarized in the introduction to his book, “[t]he defeat of Jewish revolutionary initiatives by the end of 1905 did not defeat their movement’s pioneering efforts. Jewish revolutionary socialism, largely created and emergent as a part of Russia’s 1905 Revolution, found a longer and more influential life in Palestine, Europe, America, and post-1917 Russia”—as it did in Hungary in 1918–1919.

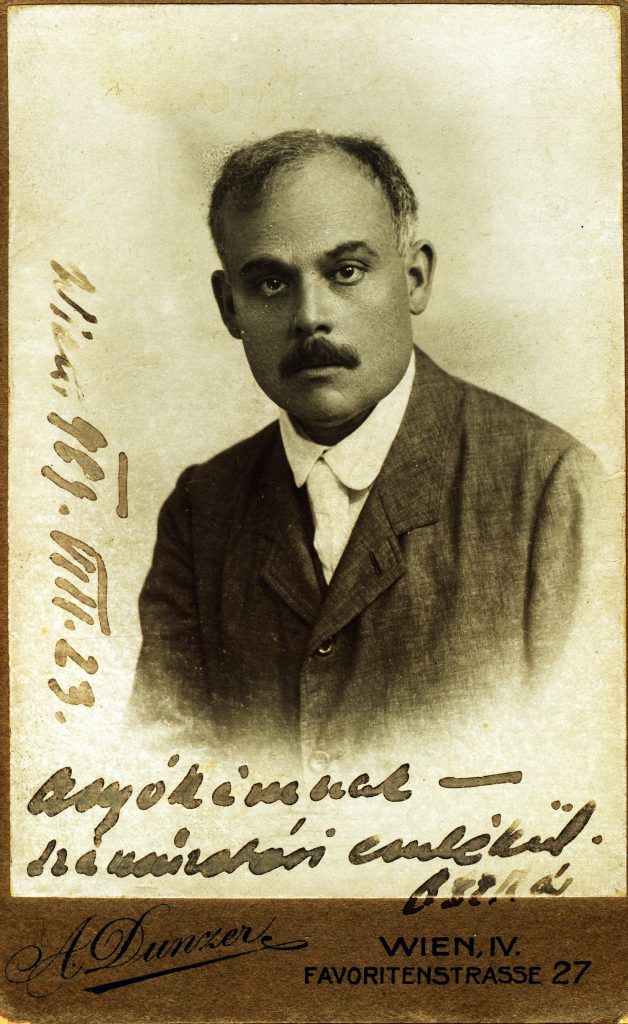

Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu)

Oszkár Jászi (source: szevi.hu)

Jászi (1982, p.69) admits in a speech to a public assembly on August 7, 1906, that “a very large role” in causing Hungary’s poverty is played by what he simply calls “Jewish usury.” In his view, the Jewish question is nothing more than “group antagonism complicated by racial frictions” (ibid., 263), not in a biological, but in a historical sense. As he points out, “haute finance and commerce are predominantly Jewish occupations, and the conflicts of interest inherent in these operations easily take on a sectarian or racial color” (ibid., 264). Jászi explains the differences between the two ethnicities, the Jew and the Hungarian, such as the excessive rationalism of the former, his alienation from nature, his crude, arrogant, pushy character, in contrast to the peasant character of Hungarian provincialism, which he believes naturally leads to antipathy. In his view, one of the causes of the “Jewish question” was to be found in the “overwhelming and pathological influence of Jewry” (ibid., 489). As is often the case when a Jew engages in a relatively honest analysis of the Jewish–gentile conflict, Jászi here comes very close to the views of the “anti-Semites”—in this case, to the summary of Hungarian grievances put forward by the Tharauds (2024, 160–163), which basically says the same thing about Jews and why they arouse antipathy.

Jászi is also quoted by the American-Israeli historian Ezra Mendelsohn, after pointing out that “the number of Jews who occupied prominent positions in Kun’s ill-fated one hundred-day regime was truly remarkable. According to one student of this period, of twenty-six ministers and vice-ministers of the Kun regime, twenty were of Jewish origin” (Mendelsohn, 1993, 894). He sums up the situation later: “Not only did Jews dominate the Bela Kun government, but they were also very prominent in the prewar ’Galileo Circle,’ the center of Budapest student radicalism, and in the prewar socialist movement” (ibid.). The author quotes Jászi as saying that “[t]he Hungarian people is much more rural, conservative, and slow thinking than the Western peasant peoples. On the other hand, Hungarian Jewry is much less assimilated than Western Jewries, it is much more an independent body within society, which does not have any real contact with the native soul of the country” (ibid., 895).

According to Mendelsohn, however, “the fact is that most Jews were patriotic Hungarians who were extremely hostile to Bolshevism”—a rather hyperbolic claim. But putting that aside, he greatly simplifies the issue: the animosity of Hungarians against Jews was the result of many factors, of which Bolshevism was only one. Hungarians noticed that Jews—as admitted by the very prominent Jászi above—formed an alien society within society, and given their enormously oversized presence in positions of influence, had a serious transformative effect on the nation as a whole. (As another source of hostility, recall Jászi’s acknowledgment from elsewhere that 90% of usury is practiced by Jews.) Indeed, the psychoanalyst Sándor Ferenczi, who was closely associated with the Galileo Circle, was not very fond of Bolshevism, and neither were some of his friends from the Circle (while others did participate in the Kun regime). And yet they had a very anti-traditional, corrosive influence on elite culture in Hungary. The conflict remains, whether Zionists, or non-Zionist Communists, perhaps Capitalists, landowners, merchants, journalists, artists, and a long list of different positions.

Identity, and Identity by Proxy

Considering the fact that the “explainers” are fond of repeating that Bolshevik Jews had no Jewish identity (which is demonstrably untrue, at least in some particular cases; see below), another point to raise here, therefore, is that of honesty. We don’t know how honest these characters were in their communications and expressions; therefore we should be cautious in assuming that the absence of something in communication proves an absence of that thing on a deeper level. A diaspora people developing proxies for group identity would not be a surprising tendency, especially during times of intergroup tensions: “Communism was, among other things, a form of assimilation” for Jews, opines Krajewski (2000), portraying them as longing to belong to a society while at the same time attempting to transform it into something very different. Yet this “seemed the most promising way” for them to assimlate. He notes, however, that “[w]hen they became rejected or just disenchanted they often ‘regressed’ to Jewishness.” This is more consistent with the possibility that Jews developed a mask for their Jewish self-image subconsciously (portraying themselves as mere socialists), or perhaps this was a consciously strategical, deceptive narrative, to appeal to masses—which returns us to the question of honesty. Indeed, for instance “[t]he idea that the victory of socialism depended on winning over the peasantry was to become one of the few political principles that [József] Pogány would continue to cling to over his entire career as a revolutionary” (Sakmyster, 2012, 30). Consciously avoiding manifestations of Jewish identification would also be consistent with the concern these Jews had about anti-Semitism—which was, indeed, the motivation behind their desire to portray their regime as less Jewish than it was (seen earlier in this study).

Appealing to peasants would not work under the flag of the Star of David, just as transforming society to cleanse it of anti-Semitism and render it safer for Jews—where Jews, indeed, would be the rulers—would not be important for a significant enough mass of people (it’s likely that they would oppose it, in fact). Using a mask—such as gentiles as leaders of a movement—to appeal to the broader gentile society is a well-known phenomenon among activist Jews (among psychoanalysts, leftist radicals, and Boasians, see: MacDonald, 1998, Ch. 2, 3, 4; Csonthegyi, 2023; 2024). Adopting proxies for the sake of “assimilation” (or perhaps for strategy), while remaining Jewish, might also remind us of the fifteenth-century Marranos, amongst whom we can also find this regression to Jewishness (MacDonald, 2003, Ch. 4). Regarding the pursuit of Jewish interests under the red, rather than the Jewish, flag, Jaff Schatz (1991, 230) notes notes that “[t]he activists were guided by an ambition to shape Jewish collective postwar life according to the content of their ethnopolitical vision. In this vision, Jewish secular culture would bloom under Socialist conditions.” Jews saw the triumph of Communism as “a remedy to anti-Semitism, backwardness, misery, and other Jewish problems in a changed Jewish occupational structure” (ibid.). We are thus again back at the transformation of host societies according to specifically Jewish perspectives.

Schatz reflects on this as well when he describes a specific type of Jewish Communist: “[r]ooted in a Jewish prewar world, they shared the activists’ vision of combining socialism with the preservation and cultivation of a secular Yiddish culture, without sharing the latter’s Machiavellian sophistication” (ibid., 237). The main leaders of the Red Guard of the Kun regime (with the exception of Ferenc Jancsik) were all Jews: Ernő Landler, Dezső Bíró, Ernő Seidler, Ferenc Rákos, Ede Chlepkó, Mátyás Rákosi. Ignác Schulz was “a former deputy commander of the Budapest Red Guard” (Simon, 2013, 61). Sándor Garbai, president of the Kun regime, recalls about Schulcz—who participated in the 1918–1919 revolutions and later moved to Czechoslovakia, still being active, but later lived in Israel, where he died—and that he followed traditional Jewish customs: “I myself have seen, and in many cases observed, that there are only Jews in Ignác Schulcz’s circle of friends and surroundings. This does not happen by chance. Schulcz still lives correctly inwardly, in the spirit of the ghetto. He observes all the injunctions of Jewish tradition, from the enjoyment of kosher cuisine to the exact observance of the long day [Yom Kippur]” (Végső, 2021, 232). This further illustrates that being an internationalist Communist-Socialist was able to coexist with a Jewish identity, refuting philosemitic mainstream tropes about this supposed impossibility. (Recall also Oszkár Jászi’s view on revolutionary Jewish nationalism.)

Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917

Some members of Po’alei Zion in Łowicz, 1917

We should also take note of the historical existence of specifically Jewish-identified Socialist groups, like the General Jewish Labour Bund in Lithuania, Poland and Russia, the Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party also in Russia, or the Marxist-Zionist Po’alei Zion (“Workers of Zion”) movement at various places in the Pale of Settlement. Moses Hess, clearly with a Jewish identity, as one of the pioneers of Zionism—and specifically of Labor Zionism—was himself a socialist. As the Enyclopaedia Judaica (2007, 704) reminds us: “An outstanding figure of the British socialist movement was Eleanor Marx-Aveling (1855–1898), Karl Marx’s youngest daughter, who felt a close affinity with the Jewish people and affirmed that ’my happiest moments are when I am in the East End of London amid Jewish workpeople.’” We can see again that being a Communist was consistent with a Jewish self-image, despite its internationalism, and this activism can be seen in their interests as Jews. Around the time of the 1905 revolution in Russia (with Leon Trotsky as a prominent figure and in which the Jewish Bund “played an extremely important role,” Bezarov [2018, 1083]), The New York Times quoted a Jewish preacher in a January 29, 1905 article with the headline “End of Zionism, Maybe”—as saying that, in the case of a successful revolution “a free and a happy Russia, with its six million Jews, would possibly mean the end of Zionism” (quoted in Heddesheimer, 2024, 20). In other words, with the victory of the revolution, Jews would have no reason to emigrate to Palestine to build Israel.

Moreover, Mirjam Limbrunner’s examination of the Bund explicitly identifies it with Jewish nationalism: “Jewish socialists would soon realize that the popular socialist movements did not address many of the challenges the Jewish masses were facing and therefore saw the need to come up with a Jewish version of Socialism” (Limbrunner, 2019, 64). The result of this desire for group-oriented forms of politics was that “Socialism and Jewish nationalism began to merge into political movements such as the General Jewish Labor Union, in short, the Bund, which was founded in 1897 in Vilna and which would have a profound impact on the Socialist Zionists in Palestine in later years” (ibid., 64).

Limbrunner also details the work and influence of Ber Borochov (1881–1917), an important figure who developed a blend of Marxism and Jewish nationalism. Borochov’s work shows the superficiality of dismissing ethnic identity among internationalists, socialists, Marxists, or Bolsheviks. Such narratives are likely dishonest. This dishonesty was often rather explicit: if we look at the Bolsheviks of Russia under Lenin, we find a specifically Jewish section of them, with the name Evsektsiia (or Yevsektsiya; Евсекция), officially recognized “as a Jewish Communist organization,” in the study of Baruch Gurevitz (1980, 29). The role of this Jewish group was to gather the more ethnocentric Jews, carefully keeping them under the Bolshevik umbrella (and thereby weakening the Zionist movement), while allowing them to remain Jews (in a secular Bolshevik way), and continue to network with the many other Jewish groups. As Gurevitz notes, the Central Committee of the Bolsheviks ordered “the Ukrainian Communists to admit the Jewish Farband and to set up an Evsektsiia in accordance with the policy being implemented in Moscow,” and as a result, they “found Jewish sections on the local level as well as a central Evsektsiia” (ibid., 33). A similar situation occurred in Belorussia as well, but Gurevitz presents many more examples of officially permitted Jewish activism within the framework of Communism—to the embarrassment of those who still pretend that this is an impossibility. (Also recall the Jewish National Council under the supervision of the Kun regime’s Oszkár Jászi, outlined earlier.) That some Jews accused the Evsektsiia of being traitors, or even as “anti-Semitic,” because of their anti-religious and anti-Zionist stance, should be viewed as an example of tribal in-fighting that is of secondary importance to us here. Thus, while gentile nations were supposed to “wipe” their “slate clean,” Jews were active within this socialist-Yiddish-Jewish identity.

Indeed, Israeli historian, Inna Shtakser argues in her book, The Making of Jewish Revolutionaries in the Pale of Settlement, that these revolutionary Jews developed a new Jewish identity, which, however, remained a Jewish identity:

The Jewish community was the place where Jewish revolutionaries felt most comfortable. Lena, a prospective revolutionary, chose to join the Social Democrats — rather than the Socialist Revolutionaries — whom she supported politically since she assumed that in the urban-oriented Social Democratic Party she would be able to propagate her ideas among Jews rather than among peasants whom she assumed would reject her due to her ethnicity. In a Jewish setting, revolutionaries did not feel the need to pretend to be non-Jewish, and to some extent could count on communal solidarity against the authorities. (Shtakser, 2014, 128)

Here we may notice that even according to Shtakser, some Jews felt the need to present themselves as non-Jews, which brings us back to the narratives used to obfuscate the responsibility of Jews (as not even being Jews), which we have already dealt with.

Shtakser also notes that these “young revolutionaries had to make compromises regarding their internationalist identity and make it clear that they were responsible for all the Jews,” and that “[f]or a short period during the revolution, the Jewish community accepted revolutionaries and even their leadership” (ibid., 129). During these tumultuous times “they did not abandon the Jewish communities when these were threatened” and “they also took responsibility for the community and expected to be treated as insiders rather than as strangers. Militants expected to be supported and to provide support against the common enemies – the tsarist regime, which discriminated against all the Jews, and the pogromists” (ibid., 130). Shtakser concludes:

Even though young revolutionary Jews had mixed feelings about the Jewish community, it was clear that only within that community did they feel secure in their social status as revolutionaries. Whereas non-Jewish revolutionaries saw the actions of the ‘Black Hundreds’ as part of a longer political battle that they were fighting, the Jews felt that the very basis of their activism was threatened, the space where they felt secure. Their subsequent struggle against the Black Hundreds was not just a struggle for the Jewish community, but also a defence of their identity. (Ibid., 130)

Abigail Green (2020, 34) also notes that “[t]he fact that early forms of Jewish internationalism were structured by liberal preoccupations — civil and religious liberty, humanitarianism, civilizational discourse, liberal imperialism — made it possible for secular Jewish liberals to engage in collective Jewish action in the international sphere.” And Ben Gidley (2014, 62) remarks that historians tend to downplay “the extent to which these migrants had any connection to the Jewish world”; in fact, Jewish migrants had “a major impact on the development of British Marxism.” He points out how this results in contradictory perspectives: “Paradoxically, such historians have often taken at face value the radicals’ profession of an internationalism that disavows any possibility of ethnic belonging, while at the same time, they have been keen to portray the radicalism that they cherish as indigenous to English soil and not transplanted from foreign lands” (ibid., 62–63).

Even earlier, the 1905 revolution already showed that Jews perceived the revolutionary movement as in the interest of their grouIt is, therefore, not a surprise that Jews were strongly motivated. Bezarov (2021, 132) notes that “The processes of formation of the organizational and personnel structure of the Russian Social-Democracy continued during the First Russian Revolution. Jews took an active part in these processes. Their role in the organization of [the] Russian social-democratic movement and in its staffing is difficult to overestimate.” This was not just due to individual Jews playing “extremely important” roles; rather, this essentially developed into a group-identity for many—a secular form of Judaism, as Bezarov comments: “Eventually, the Jewish origin of Marx, the founder of scientific” socialism, canonized his doctrine in the mass consciousness of the urban Jewry of the Russian Empire, which awaited a new messiah who would ’brin’» them out of the ghetto of the Jewish Pale” (ibid.).

This fits with Oszkár Jászi’s perception of Jewish activism in the first decade of the twentieth century as a form of “nationalism”—even if under the flag of internationalism—and we can accurately describe the activism of Jews in Hungary at that time, whether in the psychoanalytic movement, the Galileo Circle, or Bolshevism, as activism motivated by perceived ethnic interests. To bring about change; a transformation of society to a new one, where Jews are less restricted, or threatened, and can obtain more power—a competition for resources that should not surprise those who view history through the lens of evolutionary processes, with ethnic character taken into account.

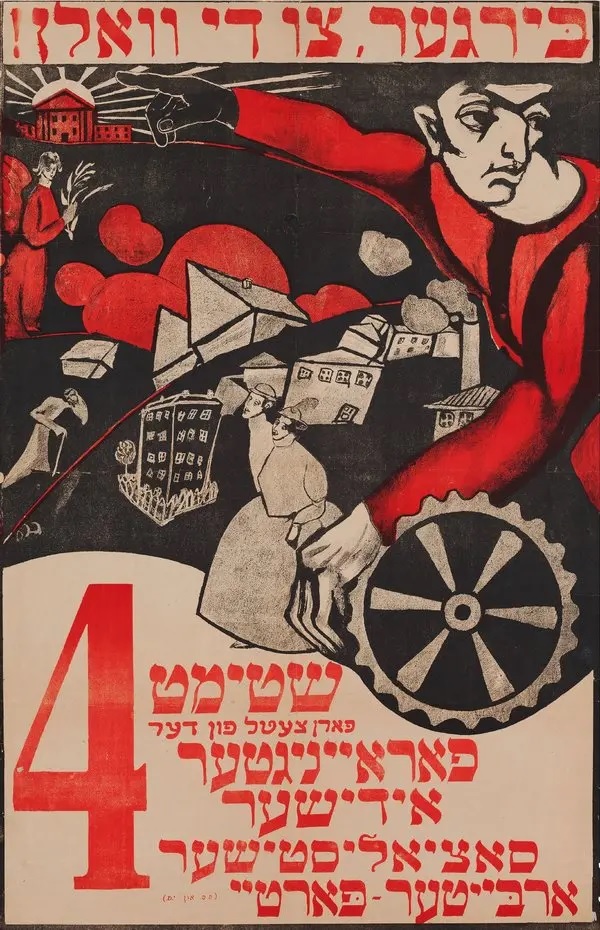

“Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)

“Vote for the United Jewish Socialist Workers’ Party” – Ukrainian election poster in Yiddish from 1917 (Ne Boltai Collection)

A key to understanding the link between being an internationalist and still possessing a particular national (ethnic) identity, is through the lens of this ethnic competition, especially from the perspective of minorities: by advocating the destruction of restrictions, the minority groups advocating for a new order where they have more freedom and access to power, engage in the pursuit of their group interests. How much of an advocacy of that sort is cynical and deceptive, and how much is genuinely believed, is often hard to know, but in the case of the latter, the phenomenon of self-deception is well-understood in the relevant literature: von Hippel & Trivers (2011, 1; see also MacDonald 2003/1998, Ch. 8) argue that “self-deception evolved to facilitate interpersonal deception by allowing people to avoid the cues to conscious deception that might reveal deceptive intent.” And Mijović-Prelec & Prelec (2010, 238) conclude that “[l]ike ordinary deception, [self-deceptoin] is an external, public activity, involving overt statements or actions directed towards an audience, whether real or imagined.”

A remark from the “non-Jewish Jew” Marxist historian, Isaac Deutscher (1907–1967) provides an interesting perspective on self-deception (assuming he is not being outwardly deceptive): “Religion? I am an atheist. Jewish nationalism? I am an internationalist. In neither sense am I therefore a Jew. I am, however, a Jew by force of my unconditional solidarity with the persecuted and exterminated” (Deutscher, 2017, 50). Here Deutscher is identifying with his own group, but gets there not in a way he finds objectionable. Instead, he rationalizes a Jewish identity as the result of a humanitarian, moral stance. But Deutscher would not, and did not, identify as a Palestinian because of all the persecution and ethnic cleansing that this specific group was subjected to around the same time (and ever since); he did not identify as a Russian or Hungarian because of the persecution those people faced under Communism, neither did he identify with any Asian or African people who endured persecution, oppression or mass murder on a large scale. His humanism appears highly selective and he, it so happens, ends up feeling solidarity with his own people for humanitarian reasons, as a foundation of his consciously accepted identity and ethnocentrism. Deutscher then goes on to note that “I am a Jew because I feel the Jewish tragedy as my own tragedy; because I feel the pulse of Jewish history,” and concludes the remark by expressing a desire to “assure” a real “security and self-respect of the Jews” (ibid.).

Gerald Surh (2023) has explored this aspect of Jewish activism in terms of perceived or real security, summarizing in the introduction to his book that “[a]mong Jews, a post-1881 generation began breaking with the quietism and passivity of the elders and traditional leaders. Just as Gentile anxiety and anger against Jews in 1905 was conditioned by more than antisemitism, transformations among Jews since the 1880s were due to more than resistance to antisemitism, however compelling the anti-Jewish threat.” He points out that “[t]hey organized Jewish political parties for the first time and, in response to the shock of the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, adapted them to pro-active self-defense efforts. The Jewish parties which gained a footing among Jews by defending them against pogroms in 1905, went on to play a substantial role afterward, both in Russia’s ongoing revolution and in the diaspora abroad.” Thus we return to the Jewish activism that Jászi saw, which included Bolshevism as another Jewish identity in the revolutionary era.

An argument is often made that, although Jews were heavily over-represented among the Bolsheviks and Communists, the majority of Jews as a whole did not support this. Even if one assumes that, depending on the situation, the Bolsheviks did not have more than 50% support in Jewish circles—that does not mean that Bolshevism in Hungary, in 1919, for example, was not a Jewish phenomenon. (This argument is also meant to suggest that other Jews were somehow patriotic, although, if there are several anti-national movements to choose from, one cannot proclaim this merely on the basis of the support of one branch.) The distribution of Jewish votes at the time—related to Surh’s insight above—is revealing, for example, in an analysis of 1917 data from Russia, summarised by Simon Rabinovitch (2009, 216): “The large number of Jewish parties vying for Jewish votes in 1917 reflected ideological divisions among the most politically active segment of the Jewish population. This political fractiousness, however, for the most part did not carry over to the Jewish masses, who overwhelmingly voted for Jewish national coalitions favouring Jewish civil equality and collective rights within a generally liberal framework.” The author adds about the coalition that received by far the most votes: “To vote for the Jewish National Electoral Committee or the Jewish National Bloc in 1917 meant to vote for a list of Jewish candidates whose priority in the All-Russian Constituent Assembly would be Jewish advocacy and defence, not merely civil equality for all (such as the Kadets) or class struggle (such as the socialists, Jewish and otherwise)” (Ibid., 217). Which is to say, political activism for Jewish interests, which is understandable, but the suggestion that “not all Jews” supported the Bolsheviks does not imply identification with the host nation, only different strategic perspectives within a Jewish framework. And finally, it doesn’t account for the fact that there was a major shift toward much greater Jewish support of the Bolshevik regime after it came to power (e.g., Slezkine 2004; Bemporad, 2013).

Under the red flag, we find Jewish identity and activism elsewhere, too. Demonstrating a strong Jewish identity among Communists, this time in the United States of the 1930s, Bat-Ami Zucker (1994, 175) details how “the ’Jewish Bureau’ was not autonomous but an integral part of the Communist Party and, as such, subject to its Central Committee, it nonetheless expressed a Jewish identity, which led—albeit indirectly and unintentionally—to the development of a unique Jewish leftist culture.” Zucker presents examples of these Communist Jews attempting a strategy in which they rejected a “national” and “Jewish” perspective, instead, they phrased it as being “Yiddish” (a mild case of identity by proxy). This changed after a few years, however:

The new positive attitude toward Jewish culture was manifested in several well-planned programs. The Jewish communist publications started promoting Jewish culture and Jewish heritage, using for the first time—though with reference to Jewish masses—the term “Jewish people” applying a positive connotation. Instead of earlier miserable attempts to justify the use of Yiddish, Jewish culture was granted a prominent role. (Ibid., 180)

Zucker quotes Moissaye Joseph Olgin, a Communist from Soviet Russia, who participated in the 1905 revolution, but ended up a journalist in the United States, as saying that “the main objectives” of these new Jew-friendly Communist policies “were to defend the Jewish people and its culture, to promote Jewish culture and to spread it among the Jewish people” (ibid., 181). These new policies included “the institution of a ’World Alliance of Jewish Culture—IKUF,’ the creation of local branches under an international committee, and the founding of a special periodical dedicated solely to Jewish culture—Yiddishe Kultur” (ibid.). This was not done merely by Communists, but achieved by specifically Jewish activism, as Zucker clarifies: “the separate organization of the American Jewish communists and especially its press, educational network, and social and cultural activities led in the 1930s, to the creation of a unique Jewish culture. Though they considered themselves loyal communists and adhered to communist beliefs, they never let go and kept proclaiming that they belonged to the Jewish people” (ibid., 182).

Shifting our attention to a different region and era, regarding the period after the Second World War, Anna Koch (2022, 111) notes that in the Communist German Democratic Republic (GDR) “Jewishness continued to play a role” even in the lives of Jews who were not close to their Jewish background anymore, not to mention other Jews who “had always seen their Jewishness as an integral part of their self-understanding and had turned to leftist politics to battle antisemitism, perceiving their antifascism to be intertwined with their Jewishness” (ibid., 111–112). As she notes: “In contrast to much of the literature that brushes aside the Jewish origin of these German Communists as being of little relevance, this chapter highlights the myriad ways in which they positioned themselves in relation to it” (ibid., 112). Koch includes in her analysis those who did not (at least explicitly) identify as Jews, but regardless, they were also motivated Jewishly.

Following Koch’s focus on the GDR, and proposing to show “how Jewish leaders rendered Communist antifascism Jewish,” David Shneer (2022, 156) elaborates on this theme: “even after the postwar purges of Communist Jews from the leadership of GDR Jewish institutions in 1952–1953, there still existed a global Communist Jewish community. Before World War II, communicating usually through Yiddish, this community played a central role in shaping modern Jewish life as it advocated for a Marxist approach to injustice and for the liberation of all peoples, including Jews, from structural systems of domination like fascism and colonialism” (ibid., 154). These Jews “found political and cultural space in the GDR in general, and in East Berlin in particular” as “GDR’s Jews inserted Jewish culture and memories of the war into the GDR’s memorial culture, thereby ensuring that Jewish memories of the war were invoked in the state’s public antifascist culture” (ibid.). Schneer then looks into the networking of these Jews, that he calls “transnational,” mostly focusing on the GDR, Hungary, and the United States—indeed, he notes that “Hungary served as a primary node of Judaism in the Communist Jewish world,” partially because “Budapest maintained the only rabbinic seminary in Communist Europe, the Budapest Rabbinic Seminary” (ibid., 163). These Jews in the GDR “were integrated into transnational and global networks that helped them maintain a sense of Jewish community through Communist networks. These other Jews created community through an older Communist tradition of Jewish universalism that had been popular before World War II, primarily but not exclusively through Yiddish culture” (ibid., 168). Robin Ostow’s interview with a woman who left Germany in 1933, but moved back from Soviet Russia to the GDR later, also details her explicit Jewish identity together with her professed Communism (Berliner, 1989).

Staying for a moment with the volume that features the essays from Koch and Shneer, and within this, with Hungary, it is worth mentioning the work of Kata Bohus, who analyses Jewish activism in the János Kádár era (1956–1989) and presents the narrative that was emerging at the time in the context of the Magyar Zsidó Jewish publication, quoting that “[t]he Jewish question is actually a Hungarian question. The question of the democracy, tolerance, openness and moral standards of Hungarian society, the question here is whether the contradictions of our society can be resolved freely, without aggression….” (Bohus, 2022, 247) This is the framework within which mainstream historiography is currently living: the crimes and responsibility of the Jews are to be attributed to the Hungarians, because of their intolerance, as we have seen earlier.

We will, however, stick to the Jewish character of the Jewish question, and thus turn our attention to the victims of the Jewish terror: we will put the complications of the “Jews were just as much victims of Bolshevism” narrative under the magnifying glass, and the blurring of Jewish responsibility for the Lenin Boys, in the concluding part of our study.

Bibliography

Bemporad, Elissa. Becoming Soviet Jews: The Bolshevik Experiment in Minsk. Indiana University Press, 2013.

Berliner, Clara. “Returning to Berlin from the Soviet Union.” In: Ostow, Robin. Jews in Contemporary East Germany: The Children of Moses in The Land of Marx. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK, 1989. 83–90.

Bezarov A. T. To the Question of the Place and Role of the Bund in the Processes of the First Russian Revolution. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 2018, vol. 63, issue 4, 1082–1099.

Bezarov, O. (2021). Participation of Jews in the processes of Russian social-democratic movement. History Journal of Yuriy Fedkovych Chernivtsi National University, (53), 131-142.

Bohus Kata. “12. The Opposition of the Opposition: New Jewish Identities in the Illegal Underground Public Sphere in Late Communist Hungary”. Jewish Lives under Communism: New Perspectives, edited by Katerina Capková and Kamil Kijek, Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2022, 236–252.

Csonthegyi Szilárd. A liberalizmus elfajzásának zsidó alapjai (I–V. részek) [Jewish Foundations of the Degeneration of Liberalism (Parts 1–5)] Kuruc.info, February, 2024.

Csonthegyi Szilárd. Így jutottunk el idáig: zsidó aktivizmus a fajrealista berendezkedés trónfosztására (I–III. részek). [This is How We Got Here: Jewish Activism to Dethrone the Race Realist Establishment (Parts 1–3)] Kuruc.info, January, 2023.

Deutscher, Isaac; Tamara Deutscher (ed.). The Non-Jewish Jew And Other Essays. Verso, 2017.

Encyclopaedia Judaica. (San-Sol), Second Edition, Volume 18. Macmillan, 2007.

Gidley, Benjamin (2014) Towards a Cosmopolitan Account of Jewish Socialism: Class, Identity and Immigration in Edwardian London. Socialist History Journal 45 , 61–79. ISSN 0969-4331.

Green, Abigail. “Liberals, Socialists, Internationalists, Jews.” Journal of World History 31.1 (2020): 11–42.

Gurevitz, Baruch. National Communism in the Soviet Union, 1918–28. University of Pittsburgh Press, 1980.

Heddesheimer, Don. The First Holocaust—The Surprising Origin of the Six-Million Figure (6th Edition). London: Armreg Ltd., 2024.

Jászi Oszkár. A nemzeti államok kialakulása és a nemzetiségi kérdés. Budapest: Grill Károly Könyvkiadóvállalata, 1912.

Jászi Oszkár. Jászi Oszkár publicisztikája. Budapest: Magvető Könyvkiadó, 1982.

Jérôme Tharaud, Jean Tharaud. When Israel is King. Antelope Hill Publishing, 2024.

Koch, Anna. “6. “After Auschwitz You Must Take Your Origins Seriously”: Perceptions of Jewishness among Communists of Jewish Origin in the Early German Democratic Republic”. In: Jewish Lives under Communism: New Perspectives, edited by Katerina Capková and Kamil Kijek, Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2022, 111–130.

Komoróczy Géza. A zsidók története Magyarországon. II. 1849-től a jelenkorig. Pozsony: Kalligram, 2012.

Krajewski, Stanisław. “Jews, Communism, and the Jewish Communists.” Jewish Studies at the Central European University I. Yearbook (Public Lectures 1996–1999). ed. by Andras Kovacs, co-editor Eszter Andor, Budapest: CEU (2000): 119–133.

Limbrunner, Mirjam. “The struggle between Communism and Zionism. Jewish collective identity between class and state in revolutionary Russia and historic Palestine.” Global Histories: A Student Journal 5.2 (2019).

MacDonald, Kevin. Separation and Its Discontents Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism. AuthorHouse, 2003.

MacDonald, Kevin. The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth-Century Intellectual and Political Movements. Westport: Praeger, 1998.

Mendelsohn, Ezra. “Trianon Hungary, Jews and Politics.” In: Herbert A. Strauss (ed.). Hostages of Modernization: Studies on Modern Antisemitism, 1870–1933/39. Volume 2, Austria, Hungary, Poland, Russia. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter, 1993.

Mijović-Prelec, Danica, and Drazen Prelec. “Self-deception as self-signalling: a model and experimental evidence.” Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 365.1538 (2010): 227–240.

Rabinovitch, S. (2009). Russian Jewry Goes to the Polls: an Analysis of Jewish Voting in the All‐Russian Constituent Assembly Elections of 1917. East European Jewish Affairs, 39(2), 205–225.

Sakmyster, Thomas L. A Communist Odyssey: The Life of Jozsef Pogany/John Pepper. Budapest–New York: Central European University Press, 2012.

Schatz, Jaff. The Generation: The Rise and Fall of the Jewish Communists of Poland. University of California Press, 1991.

Shneer, David. “8. An Alternative World: Jews in the German Democratic Republic, Their Transnational Networks, and a Global Jewish Communist Community”. Jewish Lives under Communism: New Perspectives, edited by Katerina Capková and Kamil Kijek, Ithaca, NY: Rutgers University Press, 2022, 151–173.

Shtakser, Inna. The Making of Jewish Revolutionaries in the Pale of Settlement: Community and Identity during the Russian Revolution and Its Immediate Aftermath, 1905–07. Springer, 2014.

Simon Attila. “A magyar szociáldemokrácia útkeresése a húszas évek Csehszlovákiájában.” Múltunk – Politikatörténeti Folyóirat 58.1 (2013): 36–64.

Surh, Gerald D. Russian Pogroms and Jewish Revolution, 1905: Class, Ethnicity, Autocracy in the First Russian Revolution. Taylor & Francis, 2023.

Végső István. Garbai Sándor a Tanácsköztársaságról és a zsidóságról. Budapest: Clio Intézet, 2021.

von Hippel W, Trivers R. The Evolution and Psychology of Self-Deception. Behavioral and Brain Sciences. 2011;34(1):1–16.

Zucker, Bat-Ami. “American Jewish Communists and Jewish Culture in the 1930s.” Modern Judaism (1994): 175–185.

Jews are often wealthy or at least educated. They believe they are at least special, like how Parsi see themselves as special.

And Judaism glorifies only God, their God. Nothing else is praised. The result of this extreme seems to be the enslavement and total loss of self respect among those nonJews under Jewish rule. Jews revere their heritage, though some Jews mock their own heritage while seeing themselves as still better than others, and they hate the heritage of others.

However, this is just a trend.

But the full of it seems to be a hatred for smart others, good-looking others, and others who value something non-Jewish. A trend among some that needs to be understood.

It is very much a master religion that aims to dominate. But it might have originated as an extreme nationalist faith.

Slavery is obviously legal under Judaism.

I don’t know that Vikings were “better.” My goal isn’t to condemn Jews but to highlight my hypothesis of the religion. They’re a threat, but we’re not necessarily “better.” Our goal is to preserve our identity and pride. They tend to hate such things.