“Like the Roman”: Simon Heffer’s Biography of Enoch Powell

Now that immigration has become the greatest concern in the rather archaically named United Kingdom, the name of Enoch Powell is once again a familiar one in what passes for political discourse in Britain. Prime Minister Keir Starmer, in a recent speech intended to show that he is suddenly concerned about illegal immigration, claimed that the UK risked turning into “an island of strangers”. He was immediately charged by the media as “channeling Powell”, who used a similar phrase in his most famous speech. This allegation spooked Starmer, who immediately disowned the speech, claiming to have been tired when he made it, and that he “didn’t really read” the speech his advisers had prepared. Some associations are just too toxic for a modern politician.

For the political Left, of course, John Enoch Powell is the Devil incarnate —he once claimed to have shown Parliament “the cloven hoof” in a debate about devolution—and the epitome of racism, despite (as Powell claimed) never having spoken about race in his life, but only about immigration.

In fact, Powell did mention race on a number of occasions, albeit incidentally and never thematically, but his vision was not what he would have accepted as a “racialist” one. He merely, and accurately, predicted an England “rent by strife, violence and division on a scale for which we have no parallel”. For today’s Parliamentary Right, and despite his status as one of the most famous Conservatives in history, Powell is an untouchable, and it is left to the dissident Right to laud Powell as a prophet without honor in his own land.

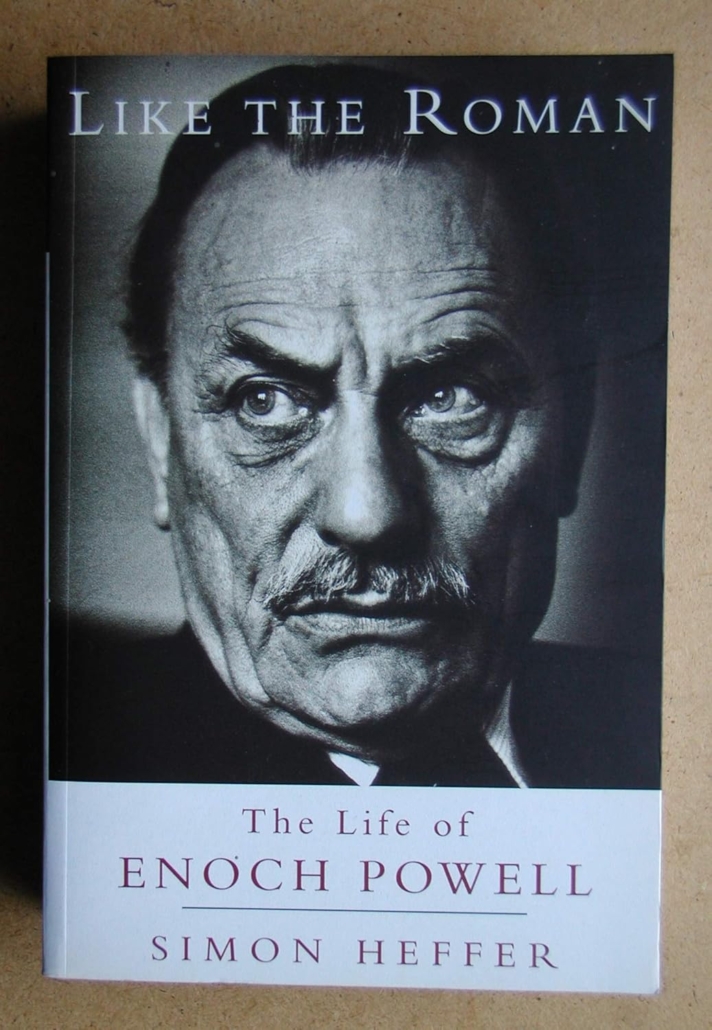

Powell did not want an official biography, believing this was the province of film stars, but his Cambridge friend Simon Heffer was accepted by the ageing politician as his biographer on condition that the book not be released in Powell’s lifetime. After Powell’s death in 1996, Heffer’s book came out two years later, a year before Tony Blair’s coronation and the beginning of the future against which Powell warned. Heffer was given access to Powell’s life, although it lacked a diary, the keeping of which Powell regarded as “like returning to one’s vomit”. Heffer added to this treasure trove by interviewing friends and colleagues. Ted Heath, the Conservative Prime Minister who called Powell a “super-egotist” and fired him as a result of the misnamed (and misunderstood) “Rivers of blood” speech, would not speak to Heffer.

Powell is remembered above all for his 1968 speech on immigration in Birmingham, but Heffer paints a broader picture of a man who excelled in everything he did. A classics scholar who took his House of Commons notes in Ancient Greek, an amateur in architecture, a noted poet, a soldier, an academic, and the speaker of half-a-dozen languages by his teenage years, Powell was a polymath who sought to put his learning to good use. Later in life, Powell also became a keen hunter at hounds, taking risks in the field but enjoying the adrenaline as a counter to the intensity of his political life.

Foremost, however, Powell was an exceptional scholar. His mother was a teacher, and Powell’s education—like John Stuart Mill’s—continued at home. His family nicknamed him “the Professor” although always referring to him as “Jack”. At the age of three he had mastered the alphabet, and ten years later, while his peers were doubtless reading comics, Powell was reading J. G. Frazer’s study of comparative religion, The Golden Bough. Later in life, on discovering another John Powell working in classics, Powell became known by his other first name, Enoch, for the rest of his life. Famously an atheist (although he would return to the Church later in life, and always referred to himself as “an Anglican”) Powell decided of the Gospel that “the historical and internal evidence would not support the narrative”. His growing love for German literature, and Nietzsche in particular, did nothing to promote religiosity in the young man. Powell read everything Nietzsche wrote, including his letters, and even admitted that his moustache was a reference to the Lutheran pastor’s son. When he flew to Australia in 1937 to take up a teaching post, the trip was a good deal more onerous than it is today, and Powell took Nietzsche’s eccentric autobiography Ecce Homo for the journey.

Powell went up to Trinity College, Cambridge, to study classics. But, on the advice of a mathematician, he also discovered economics, something which would serve him well as Finance Secretary in Harold MacMillan’s government years later. Powell read Malthus, and was impressed by the writer’s demographic insights. He was reclusive and generally shunned social company, working diligently, writing poetry, and listening to Wagner. There was a lighter side to his amusements, however, and he would mourn the death of Jacques Tati in 1982, the French comedian whose films Powell adored.

After graduating, and in search of an academic post, Powell taught in Australia, having been offered the chair of Greek at the University of Sydney in 1937. Powell was in Australia when, as he put it half a century later, “the House of Commons fawned upon a Prime Minister for capitulating to Hitler”. Two years later, Powell desperately wanted to fight in World War II, but he worried that he was on a list streaming him towards military intelligence. “I was lucky to escape Bletchley”, he observed, referring to Bletchley Park, which housed the famous British code-breaking unit led by Alan Turing and his Enigma machine. It would have been interesting to see what Turing and Powell made of one another. But in 1939 he removed that possibility by enlisting as a private soldier. “One of the happiest days of my life”, Powell recounted, “was on the 20th of October 1939. It was then for the first time I put on the King’s coat”.

As with everything he did, Powell excelled in the army, whether on the barrack square or reading Clausewitz’s On War as a means of understanding the theory of the conflict he yearned to join at the front line. Throughout his life, Powell maintained an almost morbid attachment to the wish to die fighting for his country. He reached the rank of brigadier, a title he retained in public life.

Stationed in India, Powell developed a love for that nation to the same extent he began to foster a lifelong aversion to America, “our terrible enemy”, as he described the world’s most powerful country. Powell’s view was that one of the USA’s primary aims was to end the British Empire, and he would also come to see America’s color problem as the future for Britain if immigration was not addressed. It was in India—already fluent in Urdu—that Powell first realized that his future lay in politics.

Back in England, he was interviewed by the Conservative Party and selected to fight the Parliamentary seat of Wolverhampton South West, where Britain’s housing crisis (which seems to be always with us, for one reason or another) “provided [Powell’s] first public entry into political battle”. After the war, Britain still had the slum areas it had had since the Victorian era, and Powell was determined they should be cleared. The Conservative Party in 1955 had slum-clearance as part of its manifesto, and Powell pressured them to honor that pledge.

Powell won Wolverhampton narrowly, his 20,239 votes providing a margin of victory of just 691, although in the election which followed this margin had increased to 3,196 and would rise further to over 11,000. The people liked what Powell was saying even if his Parliamentary colleagues and the media did not. Powell married his secretary, Pamela Wilson, in 1951, and Winston Churchill offered him the post of under-secretary for Welsh affairs in 1952. He turned down the great war-leader’s offer, and would not hold high office until Harold Macmillan replaced Anthony Eden in 1957 after the latter’s resignation over the Suez debacle. Macmillan made Powell Finance Secretary, perfect for a man who had read and absorbed the Austrian-British economist, Friedrich Von Hayek.

This was a good entrance on the political stage for Powell as “every spending proposal by every department came across his desk”. Decades before such things as DOGE, Powell was determined to audit and restrain the fiscal extravagance endemic to socialism, and The Daily Telegraph noted his “Puritanic refusal to countenance increased government expenditure”. Powell himself worked with maxims which, although he would review them constantly in the manner of the rigorous academic he was, provided him with a simple formula for controlling the public weal:

What matters most about Government expenditure is not the size of it in millions of pounds, but the rate it grows at compared with the rate our production grows.

Now, in an age in which successive British governments of both parties believe that the answer to all problems is to “throw more money at it”, Powell’s firm grasp of economic principles—particularly the money supply—has long since vanished.

When Powell was made Financial Secretary, the country gained a man whose mother was most worried about Powell’s childhood proficiency in mathematics and science. They were his worst subjects, thought Ellen the teacher, although these things are relative. Powell’s weakest subjects would have been many fellow students’ strongest. As an acolyte of Hayek, Powell wanted low taxes, small government, and the end to financial aid to developing countries. “Don’t give them capital”, he said of these struggling nations, “give them capitalism”. We are reminded of the adage that to give a man a fish is to feed him for a day, whereas to teach him to fish is to feed him for a lifetime. Powell was understandably overjoyed (for him) when Hayek himself suggested in private correspondence that “all our hopes for England rest now on Enoch Powell”. That said, Hayek would question Powell’s mental stability after the Birmingham speech.

It was Harold Macmillan who first brought Powell into his cabinet, during the meetings of which the Prime Minister wryly noted that Powell “looks at me … like Savonarola eyeing one of the more disreputable popes”. Throughout Heffer’s book, it is notable that politicians of the time still had a common reference point in their shared knowledge of history. In today’s UK government of midwit lawyers, no such grounding exists. Powell was given a new role as Health Minister, in which, Heffer writes, “he unquestionably laid the foundations of a modern health service”. But Heffer’s book is always leading inexorably to the turning-point which divided Powell’s political career into two halves.

While Shadow Defence Secretary, Powell forewarned of his upcoming and (in)famous Birmingham speech. “I’m going to make a speech at the weekend”, he said, “that is going to go up ‘fizz’ like a rocket. But whereas all rockets fall to earth, this one is going to stay up”. In this he was, as always, prescient. The transformation of areas of Britain, and England in particular, into enclaves in which the native population were becoming outnumbered by foreigners was increasingly being addressed at government level, and various panaceas mooted, but Powell would prove to be the coalmine canary for attitudes towards this replacement.

Powell’s Birmingham speech in April, 1968, was explosive. His beloved Nietzsche wanted his words to be dynamite, but Powell got closer to detonation than the German philosopher. And yet the blast struck both sides of the social divide. There were two attempts by fellow Members of Parliament to prosecute Powell under the 1965 Race Relations Act (there would be many more), but at the same time dock-workers—solid union men—came out on strike in protest against Powell’s subsequent defenestration. He had a speaking commission in Europe cancelled at the express instruction of the man who invited him, but he also received 4,000 letters to his private, home address, of which just a dozen disagreed with his stance in the Birmingham speech. Former colleagues in the House of Commons disowned Powell while national polling showed 75% of British people agreed with him, while 69% disagreed with Heath’s decision to sack him. Powell had divided the country, not along racial or ideological lines, but rather along class differences. But the classes had changed. Now, there was the political class and everyone else.

Powell’s prescience was not confined to his channeling his constituency in Birmingham in 1968, which he did literally. His much-quoted line about the Black man gaining the “whip-hand” over the White man was actually a comment made by one of his constituents. Powell also foresaw the rise of the Race Relations industry as well as the use that fledgling industry would be put to by the new socialism:

There are those whose intention it is to destroy society as we know it, and ‘race’ or ‘colour’ is one of the crowbars they intend to use for the work of demolition. ‘Race relations’ is one of the fastest-growing sectors of British industry.

Powell recognized that to talk of the “race relations industry” was not analogy. It really was a part of the economy, as it is today, and even more so.

Powell also predicted the arrival of BLM in the UK, which began in 2020 after the death of career criminal George Floyd thousands of miles away in Minneapolis, confessing his surprise that America’s Black Power movement had not crossed the Atlantic, and was not coming after him. Powell’s family home was under constant police surveillance, a rarity in the 1960s. The problem of immigration was moving from statistics to the real world by which those statistics are measured and to which they ultimately apply, as areas including Powell’s own constituency became overwhelmingly non-white. The public response was moving from grumbling in the queue at the butcher to flyers reading, “If you want a nigger neighbour, vote Labour”.

Powell had rushed in where other politicians feared to tread, and had opened Pandora’s jar. (As a consummate classicist, Powell would have known that “Pandora’s box” is a mistranslation). It is only now in Britain that the political class is facing up to the necessity of talking about immigration, and it would be fascinating to know what Powell would have made of the caliber of the modern politician, particularly with so many of them being women. Powell was not really a misogynist, but his regard for women was somewhat limited, viewing them as part of the “rhetoric of poetry” at best, and unteachable at worst due to their propensity to wonder in class whether they might be distracted either by the potential rudeness of the teacher, or whether or not they found him attractive.

Powell perhaps represents the last hurrah for the direct criticism of socialism in the Houses of the British Parliament. Now, it is occasionally alluded to, but only as an embarrassing family incident everyone at the dinner-table has forgotten, so best move on. Socialism remains the greatest enemy to the freedom of those who deserve, by their history, to have that freedom, and Powell knew that. He told the London newspaper, The Evening Standard, his political priority with admirable clarity: “The important thing is to get the case against Socialism heard from every platform, as often as possible”.

A ground-note to the book that sounds on every page is the radical difference in the political class in Britain then and now. Politicians were all men, and generally men of a certain class. Powell was quite a way down the British class ladder, but his formidable intellect intimidated many colleagues into seeing him as their social equal.

Powell turned down a peerage from Margaret Thatcher, with whom his relations were wary on both sides. Asked his reaction to Britain’s first woman PM in 1979, he replied simply; “Grim”. Thatcher later described Powell as the best parliamentarian she had ever seen. His speeches became the stuff of Westminster legend, and Powell understood the power of the speech. In an era when television still played a relatively minor role in political communications, he toured the country like a 1970s rock band, sometimes giving three speeches in different locations on the same day.

His forced retirement from political office meant that he had more time for reading and writing. His poetry had been highly rated by then Poet Laureate John Masefield, as well as Hillaire Belloc, and the academic studies on which he concentrated included translations of the Gospels. He also pursued a longstanding theory that the work of Shakespeare was not that of one man which, although not taken seriously by Shakespeare scholars, was grounded in long and careful study and analysis, as was every aspect of Powell’s life. Powell was modest and frugal in his lifestyle, and would have frowned on the political class’s use of luxury cars in today’s political environment. Until his involvement as Minister for Ulster rendered heightened security necessary for the Minister, Powell always walked and took the underground from Sloane Square to Westminster.

Powell was also a journalist much in demand, writing regularly for the major British newspapers (despite The Times running a leader on the Birmingham speech headed “An Evil Speech”) as well as veteran political publication The Spectator. He was even offered a place on the board of the satirical magazine Private Eye, which he turned down. Again, imagining a great meeting which never happened, it would have been entertaining to see what Enoch Powell would have made of British comedian Peter Cook, who became part-owner of the Eye in 1962.

Powell was acutely aware of the relationship, both ideal and actual, between the politician and the country he is elected to serve. Applying his scholastic standards of reasoning into this relationship, he was able to combine cynicism with accurate observation:

I am a politician: that is my profession and I’m not ashamed of it. My race of man is employed by society to carry the blame for what goes wrong. As a very great deal does go wrong in my country there is a great deal of blame. In return for taking the blame for what is not our fault, we have learned how not to take the blame for what is our fault.

Powell’s Englishness was at the heart of his belief system, and the main cause of his conflicts with both Ted Heath and Margaret Thatcher, the first of whom fired him over Birmingham, and the second of whom credited him as her biggest influence along with Sir Keith Joseph. What became known as “Powellism” was at its center a defense of an England he feared would go the same way as Empire.

What is most remarkable about Powell when compared with the current crop inhabiting—one might say “infesting” —the Mother of all Parliaments is both his sheer intellect, and the application of this gift to solvable problems. He was very aware of his academic skills, and the natural advantage it gave the conscientious politician. “I owe any success I have had”, he said, “partly to an ability to go on thinking about a subject beyond the point where other people might feel they have taken it to the limit”. Now, intellectual achievement has been devalued, but a man who could faultlessly translate Herodotus was also able to render political problems as understandable both to his colleagues and to the public at large.

His health failing, Powell suffered a fall at home which led to a brain clot and delicate surgery. He was diagnosed with the early stages of Parkinson’s Disease which, although not fatal in itself, was debilitating to a man born before World War I. When he was finally hospitalized, and being fed intravenously, he remarked that it “wasn’t much of a lunch”. He died in February, 1998, and is buried in Warwick. Would that he were living now.

Powell ahead of his time and proven right every day. Like Mosley and Joyce. And the American Rockwell. Who was deported from Britain after meeting with some allies including Colin Jordan and John Tyndall, 2 other great British men.

Powell was as right as Churchill was drunk and fat.

The sun set on the empire, now it’s all dark.

Mosley publicly campaigned against post-WW2 non-white mass-settlement in Britain some years before Powell took it up. They both said, “I cannot stand by and let my country sink.” Courageous, intelligent and patriotic, they were so different from the creeps and careerists who have sunk the ship. We can see their mistakes in retrospect but, despite differences of policy over Europe, neither are to blame for the global mess made by their enemies. Some readers may be interested in Enoch’s commentary on Matthew’s gospel, with its contrarian take on Jesus in the Jewish context.

Powell is the closest thing we have had to Hitler or de Valera.

Powell was too much of a parliamentarian, and disdained populist support. His “Tiber” speech is said to have “prevented” rather than promoted public discussion of immigration & repatriation; his language, designed to attract attention, was used by Heath to get him out of the way, even though “repatriation” then figured in Ted’s own policy. He was different from Hitler in his education, personality and economic policy.

Anyway, Hitler, De Valera, Mosley and Powell are all dead – so where do we go now?

It’s unfortunate and downright mind-boggling why a man of his mental astuteness would want to serve – and so readily at that! – to fight Hitler. Be that as it may, what was Powell’s view on Hitler, Mussolini, Mosley, and Tyndall?

Mosley failed to entice Powell into public debate.

Sansom’s novel “Dominion” attacked them both as Nazi puppets, but this nonsense was more alternative “reality” than alternative what-if history.

Powell argued in logical pyramids but the premise was not always sound.

An interesting comment by Gary Cartwright, DefenceMatters.eu, August 3, 2025, online: “Enoch Powell Spoke the Truth”.