Mortal Victims

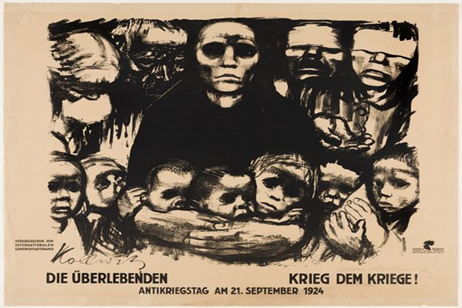

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), “The Survivors” (charcoal on toned paper)

Käthe Kollwitz (1867–1945), “The Survivors” (charcoal on toned paper)

Introductory Note:

The article below is adapted from segments of my speech, L’Histoire victimaire comme identité négative (“Victimhood History as Negative Identity”), delivered in October 2007 at the XII Round Table of Terre et Peuple, in Paris-Versailles. Nearly two decades later, I think it is appropriate to translate it into English, as it addresses the detrimental effects of various victimhood narratives. I have already written extensively in TOO about the pathology of self-imposed White guilt and self-hatred, accompanied by an almost grotesque acceptance of non-European victimhood narratives. These narratives, crafted by the Allies after World War II, have reshaped by now the identity of White nations. This postwar White identity, rooted in often exaggerated or feigned sympathy for the plight of non-European peoples, is a logical psychological and cultural consequence of the catastrophic events of World War II. It raises therefore serious questions about the future cultural and demographic trajectory of White populations worldwide.

It must be noted that the recent proliferation of victimhood narratives among growing non-White populations residing in Europe and the United States mirrors the Jewish victimhood narratives tied to World War II. Why should one ethnic or racial group be permitted to commemorate its losses while other ethnic groups are denied the same prominence for their own stories of suffering? It would be inaccurate however to solely attribute the proliferation of victimhood narratives to Jewish communities. Throughout history, and particularly after World War II, European peoples have often shaped their identities by exaggerating their own historical losses while downplaying or ignoring the suffering of their neighboring former foes. For example, as I have noted here on TOO and elsewhere, and at some point also discussed on an Israeli newscast, the ongoing memory wars between Serbs and Croats, as well as the ongoing military conflict between Ukrainian and Russian nationalists, illustrate this historical but also legal dilemma. It must be also noted that Jewish victimhood narratives—and, by extension, Jewish identity at large—are under significant strain today, particularly due to global condemnation of the Israeli government’s treatment of Palestinians in the Gaza Strip. The traditional archetype of the perpetually suffering Jew is gradually being overshadowed by the televised image of a mutilated Palestinian child, which has come to symbolize a new victimhood narrative.

** ** **

In today’s make-believe world, the projected reality must become more real than objective reality itself. Historical accounts have become more historicized than historical events themselves. To make their narratives more persuasive, mainstream historians increasingly turn to elaborate wordings filled with vivid adjectives and exaggerated body counts of their selective dead. This is particularly evident in the victimhood narratives of non-European communities residing in Western Europe and the US. These communities are searching for their victimized identity by boldly projecting themselves not just into their history, but also into their exotic prehistory. It is no coincidence that, as Europeans face a loss of their own identity, they strive to make commemorative gestures for non-Europeans. Monuments are raised for previously unknown peoples and tribes, and buildings are erected with elegant plaques to signify places of real or purported White guilt. Public holidays, or at the very least, commemorative days for non-European victims, are increasingly piling up on the calendar.

The memory of White Europeans and Americans is increasingly forced to shift toward exotic antipodes in order to pay homage to peoples whose identity has nothing to do with that of Europeans. European peoples are compelled to enter the post-historical phase of global commemoration. On one hand, the media and opinion makers assure us that History is coming to an end; on the other hand, we are witnessing a growing claim by non-European peoples to be part of their victimized history. It is as if, to have an identity, one must resurrect the dead of foreign people. As usual, external non-European victimology requires the obligatory contrition of Europeans before the Third World accompanied by the culture of remorse. The old sense of the tragic, which until recently was a fundamental pillar of European identity, is giving way to proxy lamentations for Asian and African victims. It seems that the culture of death has been replaced by a culture of necrophilia. What a horror to be unable to flaunt the dead and the victims of Others! Thus, victimology has become an important branch in the study of postmodern historiography.

We must, however, draw a clear distinction between the culture of death and the victimhood mentality, as Alain and Benoist and Pierre Vial noted in their book La Mort more than forty years ago. The victimhood mindset has entirely stripped away the meaning of death precisely because it has reduced victims to mere mathematical figures, devoid of any transcendental meaning. Where does this appetite for the dead—often for the dead of others—come from? In the hit parade of various victimhood narratives, or what’s called the “battle of memories,” not all victims are equal. Some must inevitably overshadow others. So, how do we rank the dead? In the victimhood-saturated atmosphere of today’s multicultural West, every people, every community, is led to believe its own victimhood is unique. That’s the troubling issue, given that one group’s victimology inevitably clashes with another’s.

The Ideology of Human Rights: A Discriminatory Ideology

The victimhood mentality stems directly from the ideology of human rights. Human rights, along with its offshoot, multiculturalism, are the main drivers behind the resurgence of the victimhood mindset. Once all people are declared equal, each one must be entitled to his own victimhood narrative. By their very nature, multicultural Western countries are expected to allow every community to parade its victimhood—a phenomenon we witness on a daily basis. Every ethnic group, every racial community, and even every political faction or tribe needs its own martyrology to legitimize its identity. To illustrate, let’s put ourselves in the shoes of an “Other” living in Paris, London, or New York—a Congolese, a Laotian, or someone else. Don’t they ask themselves: Why do others, like the Jews, get to have their high visibility and widely recognized victimhood narrative, but not me, why not us?

In fact, it’s in the name of human rights—and by extension, the right to victimhood—that some of the greatest atrocities of the 20th century were committed. It’s in the name of human rights that entire peoples and dissenting intellectuals are being branded as outside the bounds of humanity. The logical fallout of this victimhood mentality is the search for identity through the negation of the identity of the Other, who then becomes the primary enemy. This is the serious problem facing multicultural societies in the West. How to find a supra-ethnic, consensual discourse without excluding another community? The competition of victim narratives makes multicultural societies extremely fragile since by its very nature the victimhood mentality is conflictual and discriminatory. The language of victimhood is far more primal than the old communist doublespeak. Yet it has become the universal, global norm, inevitably leading to a global civil war.

Conclusion

Instead of reducing conflicts, the language of victimhood amplifies them; instead of fostering dialogue about identity, it destroys it; instead of honoring the dead, it reduces them to perishable objects. The image and discourse that various European nationalisms project about one another have so far relied on negative legitimacy, that is, the establishment of a negative identity. However, any victim-based narrative about European peoples invariably stirs primal emotions. The tragic Serbo-Croatian conflict is just one consequence of the antifascist victimhood discourse that dates back to the end of World War II. The causes of this World War II victimhood narrative are rarely openly debated by court historians or today’s self-righteous elites. If they do, they risk falling afoul of the penal code. Here lies a bizarre historiographic phenomenon: on one hand, we are inundated with anticolonial, antifascist, and philosemitic victimhood narratives; on the other, the colossal crimes committed by communists and their liberal allies during WWII against European peoples are rarely discussed. Who still remembers the victims of communism, who lack any recognized victimhood narrative? If there is a victimhood in Europe that truly deserves its name and merits solemn reflection, it is the tragic fate of the millions upon millions of Germans during and after World War I and World War II.

“It must be noted that the recent proliferation of victimhood narratives among growing non-White populations residing in Europe and the United States mirrors the Jewish victimhood narratives tied to World War II.”

Even Indians are trying to get in on the bandwagon. Really tiring. Jews whipping up animosity toward the majority population is enough reason to expel them.

Do the Germans have a term for their expulsion (ethnic cleansing) from Eastern Europe and general civilian suffering at the end of WWII (bombing of Dresden, Soviet violation of women)? They need some marketing term the way that Nakba, Holodomor, Holocaust work.

Speaking of Jew victims, I think Charlie Kirk was one of the most Christ like people in the spot light since Mahatma Gandhi.

[The video of the actua killl shot below is graphic parental consent may be advised]

http://livegore.com/694152/close-up-of-the-neck-shot-of-charlie-kirk