Jews and the Australian Dream, Part I: A White, Suburban City

“While the detached suburban home was seen as quintessentially Australian, the urban flat or apartment was European—French, German or more likely middle European, which like cosmopolitan was a derogatory term in this period and a euphemism for Jewish.”[1]

During the post-war era, a radical change swept across the urban landscape of the city of Melbourne, marking a turning point in its built form. A city comprised overwhelmingly of detached suburban houses began to see the large-scale emergence of a new, very foreign living typology seeking to challenge this hegemony—the flat.

Flats, also known as units, were the clustered forms of accommodation located within a single building that began cropping up en masse on allotments in the beachside neighborhoods of St. Kilda, Middle Park and Elwood. This growth started slowly at first, but caught speed in the mid-1960s, and flats were soon sprouting in suburbia at an alarming rate, an alien incursion entirely distinct from the existing dwelling and streetscape patterns. Often built in the style that became colloquially known as “six-packs,” referring to the number of flats inside, these modern multi-story buildings generally contained between 6–18 dwellings across the floorplan, thereby multiplying rents and occupants of land tenfold. Where flats appeared, private gardens and greenery withered, and what little area the building didn’t occupy was paved over for car parking and driveways to service the multiple occupants where there was previously only one. From the years 1954 until 1977, the number of occupied dwellings located within a flat complex quintupled from around 26,000 (accommodating less than 3% of Melbourne’s total population) to over 125,000.[2]

Vast swathes of streets and neighborhoods came to be dominated by these overbearing buildings, and construction of detached houses on the other hand practically disappeared during the apex of the flat boom in some suburbs. In the two years from 1962 to 1964 in the suburb of Prahran, 33 houses were built to 1,337 buildings containing flats, and in the same period in St Kilda, no houses were constructed compared to more than 1600 flats.[3] These beachside suburbs were the worst hit and the trend swept further eastwards into places like Caulfield and Hawthorn. In others suburbs, flats were kept at bay along major arterial roads, their intrusion into the depths of suburbia vehemently resisted by local councils and residents. The success of the flat typology in Melbourne and elsewhere in Australia soon encouraged developers to build higher, and Australians watched in dismay at the encroachment into their neighborhoods and their city of a high-density living style once so foreign to them, craning their heads up towards new high-rise apartment towers.

Early Flats

Prior to this boom in flats and the subsequent entry of apartments[4] and high-rise living onto the scene, Melbourne’s urban form overwhelmingly reflected the mores of its culturally and racially homogeneous white population. With plenty of land to spare, housing throughout the city was typified by detached dwellings on quarter-acre suburban blocks or double-story Victorian terraced houses within the oldest inner-city suburbs. Containing healthy backyards with space for gardening and backyard sports, these single-family dwellings were representative of the predominant desire for an overall green, low-density, private, and individualistic living style. By contrast, flats pre-World War II were a rarity all but avoided by the middle and working-class majority in nuclear family arrangements, and were confined far from the growth of suburbia.

The earliest of multi-family buildings in Australia would seem to modern observers as more akin to a hotel than a home, where instead of self-contained kitchens, they possessed a central kitchen and a staff of servants to attend to the residents in common dining rooms. These early buildings, many renovated from defunct mansions due to shortages of domestic staff (the servant problem as it was known), gave way to the first true self-contained flats during the inter-war period. Limited to the affluent suburbs, flats functioned primarily as investment vehicles and haunts for the wealthy that were never intended to displace the detached house as the main residence. They were often a convenient secondary or tertiary home for country dwellers visiting the city, rented out to the elderly and the widowed, or supplied to bachelor offspring. These flats were heavily restricted by planning codes at the time and came in the era before liberalising inventions such as strata titles and off-the-plan sales contracts. Lacking support from traditional financial institutions, which largely avoided funding them, flats were also expensive to develop. They were primarily rented out, which limited investment returns to rental returns, and where flats were sold, this had to be financed and arranged under complex Company Title laws, whereby ownership of a dwelling in a building was allocated by shareholding in a company, rather than by being subdivided into individual ownership titles. These shares could not be mortgaged and any sale or transfer of ownership had to be approved by the board of the company. Melbourne’s predominate flat architects and developers prior to World War II, the likes of Howard Lawson, and Walter Butler, operated for this small and uniformly affluent clientele in the streets of South Yarra and along St Kilda Boulevard, and the tallest residential building at the time, the 8-story Alcaston House on Collins Street, was built only a stone’s throw away from Victoria’s seat of power, Parliament House, expectedly housing the wealthy and the elite.

The Australian Dream

Subversive to established lifestyle norms and the Australian Dream, and fuelling the rise of cosmopolitanism and multiculturalism, this mass proliferation of flats and apartments in the post-war era aroused widespread and consistent angst and opposition from Australians, who were concerned about the social and cultural effect of the uptake of this new living typology on their cities. To understand the source of popular opposition to flats, as well as how radical these changes truly were, one must delve into the Australian psyche at the turn of the twentieth century, a time when a detached house was intimately linked with the emergent Australian Dream, whereas flats and apartments were linked with squalor and moral impropriety, as well as a subversive and foreign living style considered unnecessary and unsuited to the Australian way of life.

The Australian Dream, a derivation of the similar but not identical American term, grew out of the egalitarian ideals of the late 1800s and held broadly to a vision of a universally propertied nation, with the old class divides between the property haves and have-nots abolished in the New Britannia, signifying greater opportunities for social mobility and freedom. As well as its egalitarian thrust, it was believed that ownership of one’s own block of land and home, the essence of the Australian Dream, would lead to prosperity and political stability, as well as produce a healthy population living in clean air away from industrial pollution, political radicalism, and other immoral influences. At this point, the ideas of Ebeneezer Howard and the Garden City/City Beautiful movements were reaching their crescendo, and most tracts of land were subdivided in mind of a detached dwelling with plenty of space for a garden. As early as the 1930s, Australia likely held the crown for the most suburban country of all nations, as well as possessing an extraordinarily high homeownership rate, an achievement almost unmatched by other countries in the West. In the face of this distinctly Australian achievement, living in a flat represented almost a complete negation of the Australian Dream as a cultural aspiration and was in fact seen as a danger to the Australian way of life.

Butler-Bowden & Pickett argue that the prospect of mass flat living oscillated between two unwelcome extremes in the Australian mind, evoking images of Continental European hedonism and radicalism, as well as of tenement blocks and slum living.[5] Seen as crowded, unhealthy, and fostering undesirable social outcomes, the latter was in many ways a leftover of imagery from the worst days of the industrial revolution, where the influx of people into cities was followed by overcrowding, pollution and disease, and other social and political ills abounded. Socialist agitation in Europe drew much of its strength from these crowded urban masses, and the fear of falling birth rates from flat living were two political liabilities that Australia’s liberal elite were always keen to avoid. Despite this apparent contradiction in rhetoric between flats as the domain for the bohemian upper-class as well as for impoverished criminals, what was constant to all these elements was the danger to family life and the physical health of the nation, as well as an overall lack of patriotism. Whether it was the malnourished child growing up in the crime-ridden squalor of the slum flat, the bachelor-radical eschewing the bourgeois ideas of family life whilst living in the Bauhaus living-unit, or the un-married, childless heiress living in luxury in the The Astor, the threat to Australia’s future demographic vitality remained the same. Historians the likes of Charles Bean exemplified the patriotic opposition to flat living in Australia as a national danger, fearing that if flats replaced the classic Australian cottage, the ANZAC national spirit would disappear.[6]

Consequently, the first emergence of flats after World War I was a worrying portent for politicians, residents, and moral arbiters of the time, keen to see the trend limited if not outright restricted, and a variety of laws were passed throughout the states of Australia to ban them or otherwise contain them in suburbs for the wealthy, who were considered less susceptible to the detrimental impacts of flat living. The aggravated tone of the debate on flats during the interwar period is highlighted by Anne Longmire in The Show Must Go On, her history of the City of St Kilda (where the flat boom in Melbourne would soon become most apparent), quoting the vice-president of the Elwood Progress Association—an organization formed to combat flats in their neighborhood:

Flats were destructive of the best citizenship, and home builders should have the protection of the council against the intrusion of them into streets of family residences.” Supporting his case, the St. Kilda Press of 25 May 1935 argued that the city was becoming “pock-pitted” by undesirable buildings, and the one-family home would cease to exist unless zoning was introduced so that St. Kilda would not be “blighted” any further. A year later Cr. Robinson said at the annual meeting of the Progress Association that although the increase of flats had increased rate revenue, “they were attracting a type of people that were not desirable in the best interests of St. Kilda.[7]

Attitudes such as these continued to hold among the native post-war population. However, by the late 1950s the defences began to buckle as rates of migration from Europe gathered speed. Demand also came from the new generation of young adults, the nascent baby boomers, who saw flats as a “launching pad for freedom.”[8] Renting a flat or “flatting” became synonymous with unmarried youth seeking to lead transient sex lives away from the prying eyes of parents and close neighbours,[9] and flats were a cheap housing choice for young women attempting to remove themselves from the social expectations of family life. A popular example of the association of flats with sexual liberation was the subversive television soap opera Number 96, which first broadcast many of the ideas of the sexual revolution to mainstream Australian audiences. Set in the eponymous fictional flat building in the Sydney suburb of Paddington, Number 96 ran from 1972 to 1977 and featured the first homosexual and transgender characters on Australian television. Politically, flats also found currency with the forces of the New Left, whose writings rejected Australian suburban housing as a cultural malaise and who recognized the liberal and assimilationist function of the suburb as a structural and ideological barrier to their desired political changes.

The assault on Australia’s social and housing norms and traditional urban structure that began in earnest after World War II was no mean feat, coming up against deep and entrenched political and cultural opposition to these changes. The force of argument from the New Left, a handful of modernist architects, and the few extant flat developers would never be enough to convince a majority of Australians to support or even take up high-density living themselves. Instead, the task of reshaping the urban form of Australia’s cities and driving the rise of flats and high-rise living, taking advantage of the legal changes to property titles and the migrant influx, was ultimately carried out by an unyielding and determined ethnic group who were at the vanguard of these changes in almost every state in Australia. Fought primarily in the two largest cities, Sydney and Melbourne, this battle was not simply over Australia’s urban form, but over what Australia’s very future identity was to be, a fight that became a defining feature of Australia’s changing culture and demographic makeup from the 1960s onwards.

Re-shaping Melbourne

Upon investigating further, one discovers that this small, statistically insignificant group of people, primarily recently arrived migrants from Europe, made up the most prominent involvement in the post-war proliferation of flats and high-density living into what was once a solidly detached-suburban landscape. As developers, financiers, and architects, but also as residents going against the grain of the Australian Dream and the prevailing suburban living norm, it is Jews that emerge as playing the leading role in breaking through the existing stigma and cultural opposition to bring the flat and high-rise typology en masse to the city of Melbourne.

The first sign of a major break in urban form would come in 1950 with the construction of the 9-story Stanhill flats along Queens Road. Taking the title of the tallest residential building from Alcaston House, Stanhill was something altogether new for the city and challenged not only Melbourne’s height limits but its conservative architectural style. When compared to earlier flats, Stanhill, notes Sawyer:

has no suburban counterparts. Its modernity, height, high site coverage and integration of shops within the block (as opposed to flats over shops) set it apart from any other suburban [flat] block. … [It] anticipates the changing nature of inner-city suburban development, and shares design philosophies with that of luxury flat towers now being erected in St. Kilda Road, some thirty years after Stanhill’s completion.[10]

Funded and developed by Jewish brothers Stanley and Hilel Korman from Poland and designed by German architect Frederik Romberg, Stanhill’s glassy, steel-frame design exemplified a major broach of the modernist revolution in Melbourne. Romberg learnt from the Bauhaus master himself, briefly studying directly under Gropius at the ETH in Zurich; he was appalled by the architectural styles he saw upon arrival in Australia as a refugee from Europe.[11] He was committed to the social radicalism of modernist architecture, a goal ultimately facilitated by the Korman brothers, but Stanhill would end up being his largest and most famous work. A number of smaller flat buildings designed by Romberg are dotted throughout Melbourne and a 13-story bachelor flat complex in the city centre was unrealised.

If Stanhill was the early warning sign, then the rest of the army was soon to arrive. When the post-war influx of Ostjuden from Central and Eastern Europe began moving into the traditional Anglo-Jewish precinct of St Kilda and spreading into the surrounding neighbourhoods, flat developments soon followed in their wake. As O’Hanlon notes, “it is no accident that the distribution of the flats built in Melbourne in those years correlates strongly to the residential patterns of this growing Jewish community.”[12]

Aided by legal reforms to property titles (the Transfer of Land [Stratum Estates] Act 1960) and supported by the more laissez-faire local governments who saw the viability of flats as a quick solution to deal with the large migrant influx, Jewish developers led the flat development trend throughout the boom years, most prominently in the worst hit municipality—the City of St Kilda. A sample of records reveals that all five applications to build flats lodged in the month of September of 1964 in the City of St Kilda were by Jewish developers; in September of 1966 five of seven applications and in September 1968, all but one of eleven new applications for new flats that month were by Jewish developers,[13] with these figures likely replicated in other nearby councils.

Rather than operating through dedicated property development companies as is the norm today, these flats were primarily built through a collaborative approach between a mixture of builders, accountants, lawyers, architects, and real-estate agents who formed project teams (often creating a corporation solely for the building), organized investor syndicates for funds and pooled resources within the Jewish community over procuring loans from banks, which at the time were hesitant to fund flats. This hodgepodge of funding is reflected in the cheap and unintuitive designs of many of these flats, being little more than rectangular blocks with a skin of bricks. They were in stark contrast to the intricately designed Victorian terraces or Federation-era houses that sat on adjacent lots, there being neither financial means nor desire for architectural effort to assimilate the building into the local character. Dedicated Jewish developer/builders such as Martin Sachs, Adam Martin Adams of Martin Adams Developments, Jack Szwarcbord, Schlomo Itzan and Issac Hatz of Henley Constructions, and Leon Chandler left their mark on the city with countless flat developments to their name. In addition, Jewish real-estate firms Talbot & Co. and Birner Morley supplemented real-estate dealings with their own development ventures, and Jewish law firm Arnold Bloch Leibler (ABL, the law firm of Jewish activist Mark Leibler) found much of its early success in brokering for these property developments. To this day ABL continues to act as a legal advisor for Asian property developers and their apartment towers. Many flats of the era are attributable only to amateur consortiums of Jews, often family-based, who developed flats as investment projects parallel to other businesses and did not specialise in the property industry. These were primarily of the walk-up style so evident in St. Kilda, but a larger example is found in “Orrong Towers,” completed in the early stages of the boom in 1961 at 723 Orrong Road, Toorak. Designed by Herbert Tischer, the 8-story tower was built by the Tischer family-owned business Stuard Industries, which specialised in importing pianos and other musical instruments from Europe.

The Beller Boom

“I see nothing wrong with a high-rise block in a shady suburb street, provided it is designed in good taste.”—Nathan Beller[14]

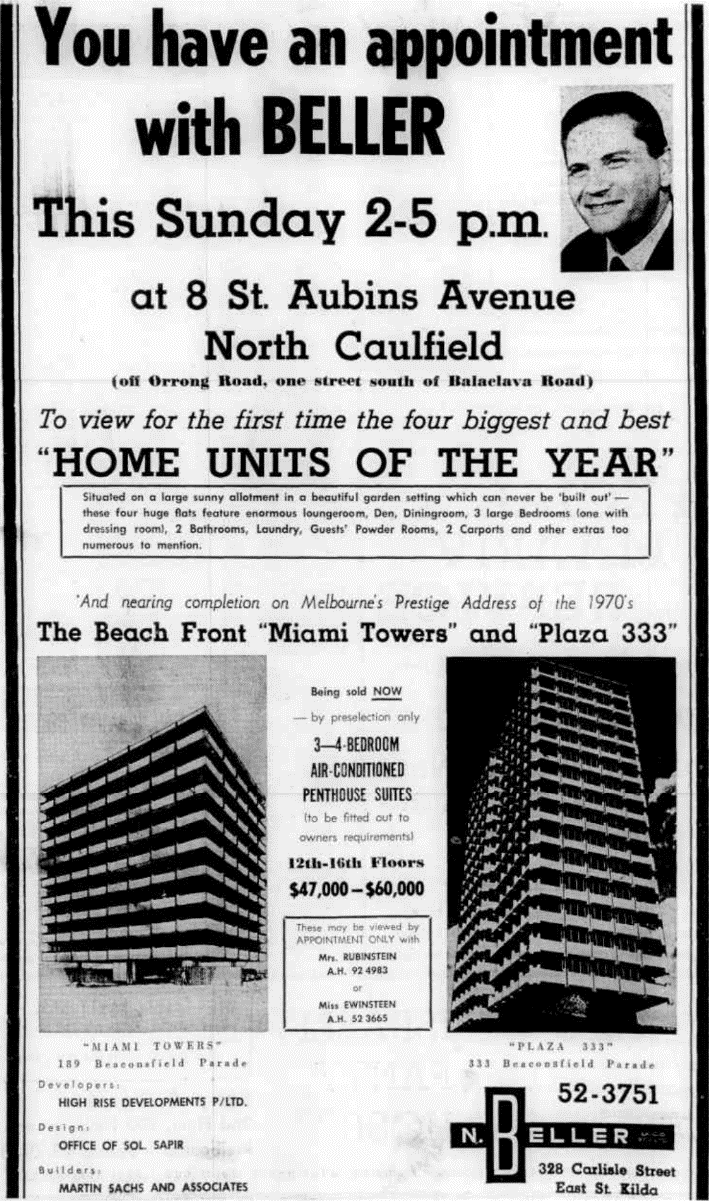

As the 1960s drew to a close, the trend did not end with 2-3-story walk-up flats. Further strata title reform came with the Stata Titles Act 1967—based upon the NSW strata law and intended to fix the deficiencies of the earlier 1960 law—which allowed the creation of a Body Corporate to control and manage common property within the building, removing responsibility for the more cumbersome upkeep of a high-rise building from individual owners. This reform opened the way for the intensification of high-rise apartment development, a market soon dominated by an enterprising Jewish developer by the name of Nathan Beller, president of the Victorian Jewish Board of Deputies from 1966–1969. The portfolio of Nathan Beller demonstrates that, emboldened by financial success and strata reform, walk-up flats gave way to taller buildings that began to tower over Melbourne’s low-density landscape. Beller, a real-estate agent by trade turned property developer, fled Austria in 1938 and was responsible for countless flats throughout the inner south and east suburbs, but he arose immediately after the strata reform of 1967 as Melbourne’s main high-rise living exponent, in a partnership with builder Martin Sachs and the architect Sol Sapir.

With Beller’s development company High Rise Developments Pty Ltd (alongside his real-estate agency to sell the flats), multiple examples of their work along the waterfront streets of St Kilda and Elwood are still the tallest structures in the area, towering over the surrounding houses. The Jewish trio collaborated on around a dozen large apartment blocks throughout the inner south-east in the short period between 1967 and 1973, and Sapir claims to have worked on the design of over 100 blocks of flats himself by the year 1971, with many more following afterwards.[15] Beller’s advertisements for high-rise flats in local newspapers promoted the cosmopolitan and progressive image of high-rise living, while denigrating those that settled into a “suburban brick-veneer rut,” the detached dwelling belittled as a “rambling workhouse that gobbled up leisure time.”[16]

Data assembled by this writer of the approximately 60 apartment buildings over 8 stories built in Melbourne between the years 1950 and 1985, indicates that more than 70 percent of these developments involved some combination of a Jewish architect or a Jewish builder/development consortium. Of this, Beller’s team was Melbourne’s undisputed leader of the high-rise trend, building more apartments towers than any other developer until the mid-1970s economic downturn hit.

Émigré Architects

In the years before the flat boom, the scanty examples of flats in Melbourne rarely exceeded 2–3 stories in height and architects would make a conscious effort to blend the built form into the low-rise streetscape, often massed to appear from the street as an English mansion or a single-family dwelling—an architectural genuflection to the desired detached-suburban form. The typical English concern for privacy was incorporated, rejecting common entrances in favour of multiple access points that led to only portions of the building or to a single dwelling. Such outcomes soon became forgotten, because even in the architectural composition of flats built during the post-war boom, the preponderance of new forms of urban thinking hostile to mainstream sentiment is evident, mostly imported from abroad by “émigré architects,” a popular euphemism for Jewish architects found in literature on the topic. The few Australian architecture firms who designed flats and high-rise buildings in Melbourne during this period (notably Moore & Hammond, who designed two larger towers along Toorak Road for suspected Jewish clients) are outnumbered by the likes of Mordechai Benshemesh, Sol Sapir (Sapirshtein), Herbet Tischer (Tichauer), Michael Feldhagen, Bernard Slawik, Theodore Berman, Anthony Hayden (Hershman), Ernest Fooks (Fuchs), Anatol Kagan and Kurt Popper, who feature among the roster of Jewish architects whose portfolios overflow with flats and towers in Melbourne. Often applying modernist styles learned in universities in Europe[17], this group of Jews has only recently seen recognition in architectural history journals, despite their overrepresentation in the trend. Earlier publications preferred to highlight the well-formed design of Robin Boyd’s sole tower output, “Domain Park” (developed by Lend Lease), rather than a dozen cheap and less palatable designs by Sol Sapir. Born in Melbourne to Jewish parents who migrated from Poland, Sapir was the most prolific flat and high-rise architect in Melbourne of this group; at least 15 high-rise blocks built during the early high-rise era, most of them developed by Beller, are attributable to him.

Of the other productive architects of this group, we find in Kurt Popper the quintessential story of a Jewish émigré architect subverting the Australian Dream. Arriving from Vienna, Popper was responsible for over 80 blocks throughout Melbourne,[18] and later became a lecturer on high-rise apartments in the School of Architecture at the University of Melbourne based off of his expertise in flat and high-rise design. These included four of the earliest apartment buildings in the central business district—city-living pioneers when Melbourne’s centre was practically deserted after business hours and was comprised almost entirely of office and retail buildings well into the 1990s. These were: Crossley House at 51 Little Bourke Street (completed in 1966 by Jewish builders Notkin Constructions), Park Tower at 199–207 Spring Street (completed in 1969, also by Notkin Constructions), 13–15 Collins Street (completed in 1970 by a Jewish development consortium), and Lonsdale Heights at 131 Lonsdale Street respectively. The at-the-time towering Collins and Spring Street buildings (22 and 20 stories each) struggled to attract local purchasers still adverse to apartment living. The Collins Street tower was partially converted into office and retail spaces and only 25 percent of units were sold in the Spring Street tower two years after completion.[19] The 20-story Lonsdale Heights tower was developed by Hotelier Les Erdi, a Jewish-Hungarian refugee, and included 135 flats alongside the Chateau Commodore Hotel. The hotel dining room became a regular venue for Zionist and other Jewish organisation meetings and Popper was a popular choice for the design of Jewish community buildings throughout Melbourne, with several synagogues, schools, and kindergartens on his resume.

Mordechai Benshemesh, who arrived in Australia in 1939 from what was then still Palestine, also dabbled in property development with his own company Lakeview Investments, alongside his flat design output. He is notable for designing the 13-story Edgewater Towers on the waterfront in Elwood for developer Bruce Small. Edgewater was Melbourne’s first residential building to exceed the 10-story mark and was arguably the first true “residential skyscraper,” taking the title of the tallest residential building from Stanhill. In 1961, his reputation as a leader in the high-rise trend became evident when he was invited to participate in a forum in Sydney alongside fellow Jewish architects, Harry Seidler and Neville Gruzman to speak on the topic of apartment buildings.[20]

Finally, Ernest Leslie Fooks’ influence is apparent not simply in his architectural output but also as an early town planner, allegedly the first lecturer on the subject at Melbourne’s Royal Institute of Technology. As a student in Vienna, Fooks was employed at the architectural firm Theiss & Jaksch and worked on the “Hochhaus Herrengasse” (built in 1930), at the time Vienna’s tallest residential building and the first non-religious building to protrude above the rooftops of the historic Viennese Old City. Proud of his involvement in the project, Fooks took his photos of the building with him when he fled Austria in 1938.[21] In 1946, whilst working as a planner at the Victorian Housing Commission, Fooks published X-Ray the City!: The Density Diagram, a novel work in Australia with an introduction by H.C. Coombs, the then federal director of Australia’s post-war reconstruction department. In it, Fooks advocated for density as a planning solution to Australia’s growing cities and the inequality of social and cultural infrastructure, and critiqued the popular sentiments that equated density with social delinquency—arguments that may have seeded some of the initiative within the state Housing Commission to build the now-hated housing commission towers. Fooks also put his ideas into practice in his private architectural output, being responsible for the design of another 40 blocks of flats in the boom suburbs during the era,[22] as well as a number of Jewish community buildings and schools, notably Mount Scopus College.

A New Generation

The financial crisis of the mid-1970s followed the suburban backlash, and, as the boom in construction ultimately dried up, the flow of new flats dwindled to a trickle. The flat boom peaked in the years of 1967–1968 where around 13,600 dwellings were added, crashing to 2,400 by 1979–1980.[23] That the high-water mark for flat development exactly coincided with the year of the arrival of the cultural and sexual revolution reflects the connection between the two phenomena. While not as fierce as in Sydney, Melbourne-based Green Bans stifled their fair share of developments, local councils tightened up planning laws, and resident actions groups began forming throughout the suburbs in response to Housing Commission towers and the flat and apartment boom. The encroachment of Jewish-built high-rise towers, in particular Nathan Beller’s, into the WASP heartlands of eastern Toorak and Hawthorn enraged locals, leading to the establishment of local anti-high-rise groups. An 8-story proposal by Beller at 480 Glenferrie Road opposite the elite Scotch College saw objectors come out in droves, his 9-story block at 3–5 Rockley Road, South Yarra (designed by Sol Sapir) was the final insult to residents on a street overdeveloped with flats, but a tower proposed in the depths of Toorak at 546 Toorak Road (built in 1971 and also designed by Sol Sapir), named Barridene after the mansion that previously occupied the site, garnered the most attention. Local residents submitted over 800 objections to the proposal and the building was eventually cut down from 19 to 13-stories, the outcry becoming the impetus for a blanket ban on more towers in the area. To this day Barridene still looms over surrounding mansions of Toorak and the Presbyterian Church across the road, the church steeple no longer being the tallest structure in the area – an apt example, in urban and built form terms, of Jewish disregard for Christian cultural mores.

Berridene

Berridene

After the flat boom ended, a calm set on the Melbourne housing market, as detached dwellings re-asserted themselves, migration slowed, and the Baby Boomers, now with children to raise, shifted to traditional detached housing. This calm would not last long however, as apartment developments re-appeared in the mid-1990s, following initiatives to revitalise the central business district and bring city-living to the heart of Melbourne. Jewish property developers came to the fore once again, former Melbourne Lord Mayor Irving Rockman’s Northrock Investments leading the way with a 58-story apartment tower proposal at 368 St Kilda Road (later reduced to 40 stories) and a 33-story tower at 265 Exhibition Street. Central Equity followed suit in the newly zoned suburb of Southbank with apartment towers at 28 Southgate Avenue and 83 Queensbridge Street, the first in the precinct; Max Beck’s Becton attempted to outdo Nathan Beller with a 38-story tower at the Espy Hotel at St. Kilda beach and Mirvac made steadily erected early towers in the re-zoned Docklands and Southbank precincts. Central Equity, co-founded and now chaired by Eddie Kutner, has become Melbourne’s most consistent high-rise property developer. Largely taking its inspiration from Meriton in Sydney, it has been churning out low-cost apartment towers in the city on average once every year since the early 2000s. The suburb of Southbank, now the tallest in Australia, is almost synonymous with the Central Equity brand—nearly 30 apartment towers south of the river now bear Central Equity’s name. A Zionist like most of his Jewish property developer kin, Kutner’s credentials have seen him involved in the Australia-Israel Chamber of Commerce, Jewish schooling and Keren Hayesod-UIA.

By the twenty-first century, other European migrant communities were also taking the limelight in roles that the Jewish community had paved the way for in the post-war era. Smaller conglomerations of flats had also sprouted in the neighborhoods of Footscray and Northcote, areas popular with Italian and Greek migrants. Italian families such as the Grollo’s, Schiavello’s and Giuliano’s grew their small construction firms into high-rise tower developers in Melbourne from the 1980s onwards, following in the wake of the Jewish community and also seeing the opportunities in flat and high-rise property development as a means of financial success. The development team of the 90-story Eureka Tower (built in 2006), up until recently the tallest building in the city and star of the rise of apartment towers in central Melbourne, symbolised the new state of affairs in property development. It was constructed by Italians (Daniel Grollo of Grocon), designed by a Greek architect (Nonda Katsalidis) and funded by Jews (Tab Fried and his brother-in-law Benni Aroni).

Although overshadowed in scale by the latest generations of property developers—now from China, Singapore and Malaysia—Jewish developers in Melbourne continue to find financial success in providing apartments for the influx of immigrants and profiting off the displacement of the Australian way of life. After 20 years, Central Equity is still going strong, and Jewish developers Meydan Group, Lustig and Moar, R. Corporation, H&F Property, Vicinity, Dealcorp, Debuilt Property, Pan Urban, and LK Property fill the spaces amongst the Asian megatowers. In an interview with a local property website, David Kobriz, the founder of Dealcorp, neatly encapsulated the hostile feeling to earlier Australian society that is now endemic throughout the industry:

Melbourne today is such a cosmopolitan place and you have to look back to the ’50s and ’60s to see where that’s come from… the third and fourth-generation migrants have made the city what it is today. Dynamic, full of variety and catering for a wide range of people.[24]

[1] S. O’Hanlon 2008, ‘Dwelling together, apart: The Jewish presence in Melbourne’s first apartment boom’, Australian Jewish Historical Society Journal 19(2), p.237-247, p.239.

[2]S. O’Hanlon 2014, ‘A Little Bit of Europe in Australia: Jews, Immigrants, Flats and Urban and Cultural Change in Melbourne, c.1935—1975’, History Australia, 11(3), p.116-133, p.120.

[3] R. Rivett, ‘Flats are Taking Over’, The Canberra Times, 14 September 1965, p.2

[4] A note on usage: In modern Australian parlance, a flat or unit generally refers to a dwelling in a smaller building, mostly the older two-story walk-up types. Once the building becomes large and tall enough for an elevator, the reference to the dwelling and the building usually changes to an apartment and apartment tower, the word apartment being a later neologism in Australia.

[5] See Chapter 1 ‘Slums of the Future?: A century of controversy’ in C. Butler-Bowden & C. Pickett, 2007, Homes in the Sky: Apartment Living in Australia, Miegunyah Press, NSW, Australia.

[6] Ibid., p.2.

[7] A. Longmire 1989, St Kilda – The Show Goes On: The History of St Kilda Vol. III, 1930 to July 1983, Hudson Publishing, Australia, p.65.

[8] R. Thompson 1986, Sydney’s flats: a social and political history, Macquarie University, p.171, retrieved from: http://hdl.handle.net/1959.14/90117

[9] S. O’Hanlon 2012, ‘The reign of the six-pack: Flats and flat-life in Australia in the 1960s.’, In S. Robinson, & J. Ustinoff (Eds.), The 1960s in Australia: People, Power and Politics, Cambridge Scholars Publishing, p.42.

[10] T. Sawyer 1982, ‘Residential flats in Melbourne: the development of a building type to 1950, Honours Thesis, Faculty of Architecture, Building and Planning, The University of Melbourne. p.46.

[11] O’Hanlon and others list Friedrich Romberg among the names of Jewish architects. Whilst also a migrant from Europe, Romberg appears not to be Jewish, rather descended from a Prussian family. The oversight potentially due to his presence in a Jewish milieu with a German surname and refugee past. Romberg fled Germany due to his left-wing views and a desire to avoid conscription into the German Wehrmacht.

[12] O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.120.

[13] O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.126. O’Hanlon sources this from the Building and Construction and Cazaly’s Contract Reporter, July-September 1964, 1966 and 1968, noting the preponderance of Jewish names.

[14] Nathan Beller quoted in The Age; ‘New Style of Life in Towers’, The Age, 19 June 1970, p.21.

[15] Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects SOL SAPIR, Retrieved from https://builtheritage.com.au/dua_sapir.html

[16] Advertisement, The Age, 3 October 1970, p.5

[17] See entries at: Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects, Retrieved from https://www.builtheritage.com.au/dictionary.html. The relative dearth of flats mentioned in the portfolios of non-Jewish architects is notable, their portfolios instead predominantly highlighting detached dwellings and commercial buildings, and flats are otherwise absent from the portfolios of Melbourne’s most prominent firms of the day such as Bates Smart and McCutcheon or Oakley & Parkes.

[18] O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.122.

[19] D. Atyeo, ‘Few takers for O-Y-O Flats in the City’, The Age, 17 February 1971, p.3.

[20] Built Heritage Pty Ltd, Dictionary of Unsung Architects MORDECHAI BENSHEMESH, https://www.builtheritage.com.au/dua_benshemesh.html

[21] RMIT Design Archives 2019, Special Edition – Vienna Abroad, Volume 9, p.41.

[22] O’Hanlon 2014, op. cit., p.122.

[23] M. Lewis 1999, Suburban Backlash—The Battle for the World’s Most Liveable City, Bloomings Books, Australia, p.91

[24] L. Sweeney, ‘Building our city: Dealcorp’s David Kobritz on the need for higher density living in Melbourne, Domain, 30 September 2019, retrieved from https://www.domain.com.au/news/building-our-city-dealcorps-david-kobritz-on-the-need-for-higher-density-living-in-melbourne-886251/