Money

(translated from French by Tom Sunic)

Of course, everybody prefers to have a little bit more than a little bit less. “Money does not buy happiness, but it does contribute to happiness” — as the saying goes. We need to find out, however, what happiness means. Max Weber wrote in 1905: “A man by ‘his nature’ does not want to earn more money; he only wants to live as he is accustomed to live and earn as much as it is necessary for him.”

Numerous investigations have pointed out a relative contrast between the rising standard of living and the level of satisfaction among individuals. Past a certain threshold, having more money does not mean more happiness. In 1974, in his studies, Richard Easterlin established that the average level of satisfaction expressed by the population has remained virtually unchanged since 1945, despite spectacular increase in wealth in developed countries. (This “Easterlin paradox” has been recently confirmed.) The failure of indices to measure material growth, such as the GDP, in order to assess the level of real well-being, is also well noted — especially at the level of a given community. There is no such service for undisputed choices that would be able to compute individual preferences in terms of social preferences.

It is tempting to see money as a power tool. Unfortunately, the old project of radical separation between power and wealth (one is either rich or powerful) will continue to be a dream. Once upon a time man was wealthy because he was powerful; today he is powerful because he is wealthy. The accumulation of money has rapidly become not the means for market expansion (as some believe), but the goal for the production of commodities. Capitalism has no goal other than boundless profit and endless accumulation of money. The skill to accumulate money obviously gives discretionary power to those who have it. Speculation with money dominates global governance. Speculative banditry remains the preferred method of capitalist hoarding of wealth.

Money should not be confused with currency. The birth of currency can be explained by the development of mercantile exchange. It is only through trade exchange that objects acquire their economical dimension. And it is also through exchange that the economic value is obtained with complete objectivity, given the fact that exchanged goods must skirt the subjective side of a single actor — so that goods can be measured in terms of the relationship between different actors.

As a general equivalent, currency is intrinsically a factor of unification. Reducing all goods to one common denominator automatically makes all exchanges homogeneous. Aristotle already observed: “All things that are traded must be somehow comparable. For this purpose currency was invented, which later became, in a way, an intermediary. It is a measure of all things.” By setting up a perspective from which the most diverse things can be evaluated through single numbers, currency makes all things “equal” ; it therefore, reduces all mutually distinguishing qualities to a simple logic of “more and less.” Money is the universal standard which ensures the abstract equivalence of all commodities. As a general equivalent it reduces all quality to sheer quantity. The market value is only capable of a quantitative differentiation.

But at the same time exchange also equalizes the personalities of those who are in the “business” of trade. By showing the compatibility of their offer and their demand, it establishes the interchangeability of actors’ desires. Ultimately, any exchange leads to the interchangeability of all human beings, who thus become objects of their own desires.

The Monotheism of the Market

“The rule of money, writes Jean-Joseph Goux, is the reign of the unique measure from which all things and all human activities can be assessed…. What we observe here is the ‘monotheistic mindset’ regarding the notion of value as a general equivalent for all things. This money rationality, based on a single standard of value, is fully consistent with “theological univalence.” This can be called the rule of ‘market monotheism.’ Money, writes Marx, is as a commodity, which leads to total alienation because it produces global alienation of all other commodities.”

Money is much more than just money — and it would be a big mistake to believe that money is “neutral.” No less than science, no less than technology or language, money cannot be neutral. Twenty-three centuries ago, Aristotle observed that “human need is insatiable.” Well, “insatiable” is the right word here; there is never enough of it. And yes, because there is never enough of it, there cannot be a surplus of it either. The desire for money is a desire that can never be satisfied because it feeds on itself. Any quantity of it whatsoever must be increased to the point that better must always mean more.

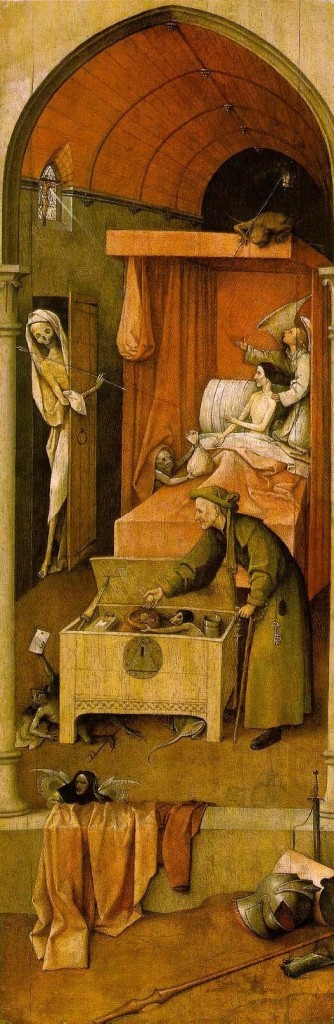

The thing, of which one can always have more, one will never have enough of. That is the reason why ancient European religions continuously warned against the passion for money:

The Gullweig myth in the Norse mythology

The twilight of gods “(ragnarökr)

All these were the consequences of the lust for money (the “Rheingold Curse“).

“We are running the risk,” Michael Winock wrote a few years ago, “of seeing money and financial success become the only standard of social prestige, the only purpose of life.” This is where we are now. Nowadays, everybody craves money all over the world. The Rightwing has been for ages its most devout servant. The institutional Left, under the guise of “realism,” espoused the principles of the market economy — that is to say, the liberal management of capital. The language of economics has become ubiquitous. Money has become an obligatory rite of passage in all forms of desires that express themselves on the trade register.

The money system, though, will not last long. Money will be destroyed by money — by hyperinflation, bankruptcy and hyper-debt. Probably, one will grasp by then that one can only be rich by what one gives to others.

Alain de Benoist is a philosopher residing in France. His websites are: http://www.alaindebenoist.com/ and http://www.revue-elements.com/. This article was originally published in Elements, January-March, 2011

Comments are closed.