Why Mahler? Norman Lebrecht and the Construction of Jewish Genius

2011 marks the centenary of the death of Gustav Mahler. This follows last year’s one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the composer’s birth. In addition to an upsurge in performances of Mahler’s works by orchestras around the world, last year also saw the release of a second book about Mahler by the journalist and music critic Norman Lebrecht entitled: Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World. This book is the latest in a long line of encomiums by Jewish music critics and intellectuals that have transformed Mahler’s image from that of a relatively minor figure in the history of classical music at mid-Twentieth Century, into the cultural icon of today. Lebrecht wants his latest work to ‘address the riddle of why Mahler had risen, from near oblivion, to displace Beethoven as the most popular and influential symphonist of our age.’[1]

Like his previous book about Mahler (Mahler Remembered) the focus here is on alerting us to fact of Mahler’s towering genius, and how this genius was inextricably bound up with his identity as a Jew. Overlaying this, as ever, is the lachrymose vision of Mahler the saintly Jewish victim of gentile injustice. Lebrecht’s new book is another reminder of how Jewish intellectuals have used their privileged status as self-appointed gatekeepers of Western culture to advance their group interests through the way they conceptualize the respective artistic achievements of Jews and Europeans.

Through stressing, as Lebrecht does, the Jewish origins of figures like Mahler, Jewish intellectuals have made them personifications of a specifically Jewish genius (‘Einstein’ did not become a synonym for ‘genius’ by accident). All of the Jewish intellectual gurus discussed in The Culture of Critique had their legions of Jewish acolytes in the academic world and in the media, and they were strongly supported by the wider Jewish community (summarized here, especially pp. 231-232). This betokens an acknowledgement of the importance of ethnic role models in the promotion of ethnic pride and group cohesion, and how ethnocentric Jews, like Lebrecht, have hyped the former to promote the latter. This form of Jewish intellectual activity is clearly directed at influencing ‘social categorization processes in a manner that benefits Jews.’[2]

Constructing Mahler as Jewish Genius

The clear tendency among Jewish intellectuals has been for Jewish achievement to be overstated and particularized and made a locus for ethnic pride. Meanwhile, European achievement is downplayed, or where undeniable, universalized and thereby neutralized as a potential basis for White pride and group cohesion. Accordingly, the racial origins of Shakespeare are de-emphasized (scarcely an Englishman or European) and he is instead held up as an exemplar of a ‘universal human genius’ whose astonishing abilities are supposedly latent in all branches of human family (see, for example, Harold Bloom’s Shakespeare: The Invention of the Human). The alternative approach has been to claim that Shakespeare’s works were actually written by a Jewish woman named Amelia Bassano Lanier. Contrastingly, Mahler’s achievement is held to be specifically and inseparably Jewish, and a reflection of Jewish intellectual brilliance.

This raging hypocrisy is bad enough. However, the duplicity is made the worse by the vast cognitive dissonance involved in simultaneously denying the reality of a collective White racial achievement, while stridently affirming the reality of a collective intergenerational guilt that must urgently be instilled in all White people. Intellectual consistency is ostensibly less important here than spreading the meme that: Whites can only be criticized as a group, never praised — while non-Whites (especially Jews) can only be praised as a group, never criticized.

The cult of Mahler since the sixties is an object lesson in the role of Jewish ethnic networking and ethnocentrism in the construction of what now passes for Western culture. Lebrecht openly acknowledges that the core of Mahler’s support, even during his own lifetime, had a foundation in Jewish ethnic networks. He points out that: ‘Not just in Berlin… but in Hamburg, Munich, Leipzig and Vienna, the Jewish middle classes formed the core of Mahler’s audience… Mahler would have known, much as Saul Bellow and Philip Roth did in Chicago and New York, that there were people who queued up for his next work. They might not understand it or even like it, but they demanded the installment as of right, as their stake in his story. It was this public that gave Mahler the confidence, in the face of racist opposition, to carry on composing.’[3] Mahler’s core group of friends, associates and supporters were no exception. Mahler’s wife to be, Alma Schindler, noted in her diary that Mahler’s friends were ‘all conspicuously Jewish’.[4] From then to now the propagation of the cult of Mahler has been predominantly a Jewish affair.

Perhaps the most prominent and influential proponent of the ‘Mahler as Jewish genius’ trope was Leonard Bernstein who attributed to the composer superhuman powers of prophecy. In 1967 he claimed that it is ‘only after we have experienced all this through the smoking ovens of Auschwitz, the frantically bombed jungles of Vietnam, through Hungary, Suez, the Bay of Pigs, the farce-trial of Sinyavsky and Daniel, the refuelling of the Nazi machine, the murder in Dallas, the arrogance of South Africa, the Hiss-Chambers travesty, the Trotskyite purges, Black Power, Red Guards, the Arab encirclement of Israel, the plague of McCarthyism, the Tweedledum armaments race—only after all this can we finally listen to Mahler’s music and understand that it foretold all.’[5]

Lebrecht, taking up where Bernstein left off, is likewise convinced that Mahler is more than just a great artist. ‘Music, in Mahler’s view, did not exist for pleasure. It had the potential for a “world-shaking effect” in politics and public ethics.’[6] Moreover, the man and his music are said to be ‘central to our understanding of the course of civilisation and the nature of human relationships.’[7] His symphonies are prophesies of war, modern technology, and environmental degradation. For Lebrecht, in Mahler’s Third and Seventh symphonies he hinted at a future ecological disaster; in the Sixth he warned of an imminent world war. “His First Symphony tackled child mortality,” while “his Second denied church dogma on the afterlife.” The Fourth symphony is said to have ‘proclaimed racial equality.’[8]

This kind of overblown rhetoric is too much even for Philip Kennicott, the music critic for The New Republic, who notes that: ‘Mahler is not the only artist who attracts this sort of nonsense, but his partisans seem particularly inclined to it, in part because the composer lived during a period of great intellectual foment…. The truth of Mahler’s complicated life is more interesting, and more stirring, than Lebrecht’s attempts to cast him as an artistic superhero and a Jewish victim.’

Constructing Mahler as Jewish Victim

The cult of Mahler as noble Jewish victim was first given impetus by Arnold Schoenberg (himself an ethnocentric Jew and Zionist) who ‘canonised Mahler as “this martyr, this saint” and in a Prague lecture in March 1912 announced: “Rarely has anyone been so badly treated by the world; nobody, perhaps, worse.”’[9] Frankfurt School music theorist Theodor Adorno took up the theme in 1960, affirming that: ‘Mahler’s tonal chords, plain and unadorned, are the explosive expressions of the pain felt by the individual subject imprisoned in an alienated society… They are also allegories of the lower depths of the insulted and the socially injured… Ever since the last of the Lieder eines fahrenden Gesellen Mahler was able to convert his neurosis, or rather the genuine fears of the downtrodden Jew into a vigour of expression whose seriousness surpassed all aesthetic mimesis and all the fictions of the stile rappresentativo.’[10] Over the fifty years since these statements were made, the Mahler cult of Jewish victimhood has become a cottage industry.

Lebrecht’s ethnocentric outpouring is this industry’s latest product. He sees the root of Mahler’s contemporary appeal as lying in the fact that he was ‘three times homeless’ and claimed three identities: ‘his Jewish roots, his German language and his ineluctable sense of not belonging anywhere in the world.’ Mahler is said to have had no sense of permanence. ‘”I am three times without a Heimat,’ says Mahler, ‘as a Bohemian in Austria, an Austrian among Germans and as a Jew throughout the world – always an intruder, never welcomed.” Heimat is German for homeland, for roots and birthright. As a Jew, Mahler has no place to call home.’[11] Stove points out that once this became widely known ‘his identity politics credentials became the aesthetic equivalent of a nuclear warhead, lacking only homosexuality to complete his posthumous triumph.’ Lebrecht, eager to complete the posthumous triumph, earnestly informs us that ‘Inclusivist and non-judgemental, he [Mahler] bears no prejudice against any racial and sexual minorities. The multiculturalism of his Fourth Symphony is not an empty gesture. Mahler, ahead of his time, welcomes the outsider into the fold.’[12]

Even Mahler’s birth date (July 7, 1860) is, for Lebrecht, laden with the rich symbolism of Jewish victimhood. ‘The Hebrew date is the seventeenth day of the month of Tammuz, the Fast of the Fourth Month when Jews begin three weeks of mourning for the destruction of Jerusalem in the years 586 BC and 70 AD. The fast is a warning from history, an omen of homelessness. Gustav Mahler enters the world on a day of dispossession.’[13]

That alienation,’ Lebrecht asserts, ‘so prevalent in a culturally diverse twenty-first century, gives a vital clue to Mahler’s contemporary relevance. In an age when a half-African, part-Muslim orphan from Hawaii could rise to become President of the United States of America, Gustav Mahler is finally able to find a home in our lives.’[14] If this is indeed true, it surely indicates the extent to which Jewish sensibilities have indeed become ours – the culmination of a triumphant group evolutionary strategy where the ‘otherness’ of a Jewish culture, once at the periphery of European life, has now successfully established itself at the heart of Western high culture.

Lebrecht cites several Jewish intellectual and artistic figures of his acquaintance who strongly identify with Mahler and draw inspiration from his status as the quintessential Jewish victim. A telling example is the late artist R.B. Kitaj who completed a portrait of Mahler based on a late photograph. Lebrecht recounts:

I got to know him while he was working on the portrait, his Chelsea studio stacked with packing cases, ready for his return to America. ‘The School of London is now closed,’ said Kitaj, winding up a group he formed with Francis Bacon, David Hockney, Lucian Freud, Frank Auerbach, Leon Kossoff and Howard Hodgkin. His reason for leaving was a mauling by British critics of his 1993 Tate exhibition, an onslaught on which he blamed the death soon after of his wife, Sandra Fisher, from a brain aneurysm. What the critics hated was Kitaj’s lines of comment and explanation on his paintings. Kitaj accused them of anti-Semitism. ‘Was it a coincidence that I was the only Jew who put the Jewish drama at the heart of my paintings?’ he demanded. ‘Was it a coincidence that I was the only exegete among painters?’

‘You’ve caught me at a terrible moment,’ he said when I turned up to talk about Mahler. ‘I really didn’t welcome intrusions this past year. But Mahler I couldn’t refuse.’ He had felt a kinship with Mahler since he studied in 1950s Vienna, seeing hatred in the eyes of his landlady, his tutors, the shopkeepers. ‘The streets I walked on I could have been hauled off just a few years before,’ he said. Kitaj equated anti-Semitism with anti-modernism. ‘Jewish brilliance’, he said, ‘made the modern world.’ Jews like Mahler and Kitaj were agents of change, architects of human unease.[15]

The exact nature of R.B. Kitaj’s ‘Jewish brilliance’ was manifested in a series of paintings of a voluptuous young woman, usually nude (his much younger wife), often in the company of an older bearded man (Kitaj himself). A failure to fully appreciate the aesthetic excellence and intellectual depth of such works could only, their creator reasoned, be the result of vile anti-Semitism. Readers are invited judge for themselves:

Jewish Influences in Mahler’s Music

It has long been suggested that Mahler’s music ‘speaks’ Yiddish. Rudolf Louis, a leading critic of Mahler, famously wrote in 1909: ‘What I find so utterly repellent about Mahler’s music is the pronounced Jewishness of its underlying character… It is abhorrent to me because it speaks Yiddish. In other words it speaks the language of German music but with an accent, with the intonation and above all the gestures of the Easterner, the all-to-Eastern Jew.’ Lebrecht, notwithstanding Louis’s anti-Jewish intent, would fully concur with this assessment – linking, as he does, Mahler’s characteristic musical cadences with the Hasidic klezmer bands he was exposed to as a child:

The Judaism in which Gustav Mahler is raised is lukewarm, mainstream Orthodox with infusions of other trends. He encounters Hasidic melody from itinerant klezmer bands, their music shifting, with a nod of the head, from morbid to manic and back. Klezmer is a music that obeys no code of conduct, unlike the military bands that parade daily in Iglau’s town square. A collision of army discipline and smiley Jewish individualism is imprinted on the boy’s mind. The first language he hears at home is Yiddish, a dialect made up of German, Hebrew, Aramaic and Slavonic terms with a syntax all its own. Known as mameloshn, mother’s tongue, Yiddish allows Jews to communicate in code. Double negatives are designed to confuse alien ears, along with a courtesy so elaborate that only by listening to tone and observing hand motions can anyone be sure whether a word is flattery or insult.

Yiddish rings loud in Mahler’s adult response ‘Am I a wild animal?’ he shouts at celebrity gawkers, using a Yiddish term, vilde khaye, that conveys both feral danger and boyish mischief, terror and endearment in one useful obfuscation… Crucially, Yiddish gives his music the possibility of sustaining two contrary meanings. Every innovation that Mahler makes derives from his tribal origins’[16]

For Lebrecht, in the funeral march in Mahler’s First Symphony he ‘is writing as a Jew and the irony he uses is not classical Greek but everyday Yiddish, a dialect that changes meaning by gesture and inflection. Any statement in Yiddish can be made to mean the opposite… the conjunction of gravity and gaiety is a facet of Jewish psychology and a driving motive of Mahler’s First Symphony. Played without irony, the music sounds shallow. Played with too Jewish an accent, it attains self-parody. Mahler leaves it to interpreters to strike the correct balance.’[17]

It says something of the extent of what Wagner called the ‘Jewification’ (Verjudung) of contemporary Western musical taste that audiences actually have come to prefer the Yiddish-inflected musical irony of Mahler over the sincerity of a Beethoven or a Bruckner. Of course a professed love of Mahler’s music cannot be taken at face value these days – often involving extra-musical motivations like a desire to make (through such a statement) tacit declaration of one’s political rectitude and moral purity.

As mentioned, Lebrecht is centrally preoccupied in his book with ‘seeking the meaning of Mahler in the context of his ancestry’ and how his artistic achievement was fully and happily determined by it.[18] In this endeavor he finds a parallelism between Mahler with Freud. According to Lebrecht:

Mahler’s closest affinity with a maker of the modern world was with Sigmund Freud, four years his senior and from a similar Czech-Jewish provincial background. Both built works out of incidents in their early lives. Freud predicated the Oedipus Theory on memories of urinating in his parents’ bedroom, being his mother’s favourite and seeing his father racially humiliated. Mahler, a boy who saw five of his brothers carried in coffins from the family tavern where the singing never stopped, composed a child’s funeral in his First Symphony with a drunken jig… Both men, intellectually Jewish, could sustain discrete lines of thought within a single argument. Freud’s free association is modelled on Talmudic discourse where rabbinic opinions from various places and centuries preclude a straight logical line. Mahler’s interpolation of stray horns and folk-songs reveals the same methodology… Both used their Jewishness as a shield and a sword. ‘Because I was a Jew I found myself free from many prejudices which limited others in the employment of their intellects,’ said Freud, ‘and as a Jew I was prepared to go into opposition and to do without the agreement of the “compact majority”.’ Being Jewish, said Mahler, was like being born with a short arm, having to swim twice as hard. Being ‘three times homeless’, he could ignore fixed rules. Both men felt a sense of mission to improve the world, undertaking a tikkun olam to assist and complete God’s work of creation.[19]

This sense of a ‘mission to improve the world’, supposedly shared by Freud and Mahler, inevitably manifested itself in vehement rejection of the cultural mores and consensus views of the Vienna of their time. For Lebrecht, fin de siecle Vienna was a place where the demonization of Jews’ is ‘culturally acceptable’, and where ‘the appalling prospect of genocide germinates around the Ring of Mahler’s Vienna.’[20] It is a city ruled by a militant anti-Semite [Karl Lueger] whose ‘racialism, selective and at times quiescent, can be whipped up at will against the “money and stock exchange Jews”, the “beggar Jews”, the “ink Jews” (intellectuals) and perpetually, the “press Jews”. Under Lueger, Vienna becomes the first modern city to make hating Jews municipal policy.’[21] For Mahler it is a place where ‘the forces of darkness are rallying to plot his downfall’ and where ‘everything Mahler does with the Vienna Philharmonic is tinged with an undercurrent of anti-Semitism.’[22] Vienna is a city ‘whose ideology is introspective, racist, regressive and smug’ and where ‘Mahler and Klimt represent a progressive, liberal alternative from the all-pervading unreality.’ In such a threatening environment Mahler does ‘what Jews have done down the ages. He huddles in a ghetto of close friends, almost all of them Jewish, and keeps his head down.’[23]

Constructing Mahler’s Jewish Identity

An awkward issue that Jewish Mahler-worshippers have had to deal with is the composer’s conversion to Christianity. Kennicott critiques the deceptive way that Lebrecht represents Mahler’s conversion to Christianity to secure his appointment in 1897 as Director of the State Opera in Vienna. Lebrecht is eager to present the conversion as a purely cynical manoeuvre on the part of Mahler, and one which left his strong Jewish self-identification unaltered. Lebrecht tells the story this way (citing the conductor Bruno Walter and the Austrian music critic Ludwig Karpath):

He is the most reluctant, the most resentful, of converts. “I had to go through it,” he tells Walter. “This action,” he informs Karpath, “which I took out of self-preservation, and which I was fully prepared to take, cost me a great deal.” He tells a Hamburg writer: “I’ve changed my coat.” There is no false piety here, no pretence. Mahler is letting it be known for the record that he is a forced convert, one whose Jewish pride is undiminished, his essence unchanged. [24]

Kennicott quotes the full transcript of the letter to Karpath, cited in Henry Louis de la Grange’s epic four-volume biography (with references to Mahler’s pre-Vienna post in Hamburg where Bernhard Pollini was manager of the opera):

“Do you know what particularly offends and annoys me? The fact that it was impossible to occupy an official post without being baptized. This is something I have never been prepared to accept. Of course it is untrue to say that I was baptized only when the opportunity arose for my engagement in Vienna—I was baptized years before. In fact it was my longing to escape from the hell of Hamburg under Pollini that prompted me to contemplate the idea of leaving the Jewish community. That is the humiliating part of it. I do not deny that it cost me a great effort, indeed one could say it was an instinct for self-survival that prompted me to such an action. Inwardly I was not averse to the idea at all.”

As Kennicott points out: ‘Lebrecht is too selective in his interpretation, and does not adequately confront the ambiguity of that last line: “Inwardly I was not averse to the idea at all.”… This complication does not stop Lebrecht from indulging in a line of Mahler bathos that, once again, was most fully embodied in Bernstein, but which has little scholarly support.’ Lebrecht, like Bernstein, sees Mahler as forever troubled by his conversion, leading him to a wild conjecture about another event in Mahler’s life – a mishap during Mahler’s marriage to Alma Schindler. During the wedding, Mahler stumbled, or fell, while kneeling at the altar:

Picture the scene: Anxious little Jew about to marry blond bombshell, trips over his prayer stool and falls flat on his face, ha-ha, no one laughing louder than the priest, Josef Pfob. Is this what really happens? My scrutiny of the spot suggests an ulterior scenario. Above the altar is a Baroque sunburst with four Hebrew letters at its center—yod, heh, waw, heh—the tetragrammaton that is the unpronounced Jewish name for God. Gustav Mahler looks up as he sinks to his knees, misses his footing and falls. Alma thinks he trips because he is so short. But Mahler has just seen the God of the Jews. Guilt and betrayal clog his gullet. He needs a moment to collect himself before he takes Christian vows. He falls over to gain time. Alma and the priest giggle at his discomfiture. He does not belong in church.[25]

This passage is pure fantasy which Lebrecht invents based on a few Hebrew characters in the church. Kennicott notes that there is no evidence whatever for the account, and ‘the idea that Mahler intentionally throws himself to the ground “to gain time” is completely unsupported… As for Mahler’s feelings of guilt and betrayal, here is de la Grange again: “Nothing, either in Mahler’s reported words or in his letters, betrays the slightest guilt feeling for having left the religion of his ancestors, a remorse which nevertheless has been attributed to him.”’ Undaunted, the ethnocentric and star-struck Lebrecht goes to great lengths to create this very impression:

After the act of conversion he never attends mass, never goes to confession, never crosses himself. The only time he ever enters a church for a religious purpose is to get married. His wife calls him a ‘Christ-believing Jew’ but the prayers he offers in mortal anguish, scrawled in his final score, are only to God the Father. Mahler, officially a Catholic, remains a monotheist and a Jew. He is a relic of an unending persecution, a kind of marrano, like one of thousands who went underground for centuries in Spain after Ferdinand and Isabella started burning the Jews in 1492. To Viennese anti-Semites, he is the archetypal Jew.[26]

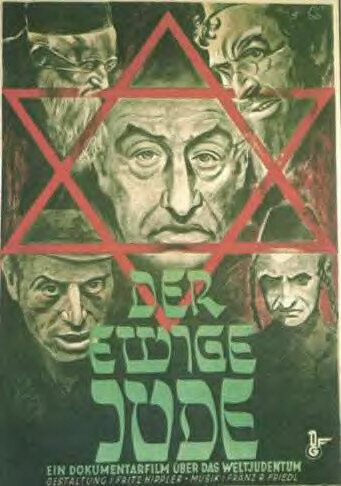

Lebrecht is at his most blindly ethnocentric (to the point of complete self-deception) in analysing the last lines of Das Lied von der Erde, or The Song of the Earth, from 1908, a suite of extended orchestral songs. He seizes on the last words of the final poem: ewig, ewig (forever, forever). In context, they are ‘typical Romantic exclamations of the numinous.’ But Lebrecht detects a deeper hidden meaning in this song-symphony:

How does Mahler pack so much emotion into so trite a word? The ‘Ewig’ enigma resisted me for years until a chance sighting at a 1988 exhibition in Vienna cracked a subconscious code. It was the fiftieth anniversary of Hitler’s Anschluss, and among the artefacts was a photograph of a railway station festooned with a banner: ‘Der Ewige Jude’, the eternal Jew. Of course, ‘Ewig’, pronounced eh-vish, has a specific connotation in the German mind. It is the Eternal Jew, the one that killed Christ and is condemned to wander the beloved earth, a touchstone of Christian theology. In 1940 Joseph Goebbels makes it the title of a film whose purpose is to justify genocide. ‘Ewig’ and Jew are linked in the German mind.[27]

This leads Lebrecht to the following conclusion: ‘“Ewig” in ‘The Song of the Earth’ is the Jew in Gustav Mahler, the alter ego, the old, real Mahler he manages to rediscover as his life enters its closing phase.’[28]

Kennicott points out that, once again, there is no evidence for this conjecture, which is based on connecting a single word from a song text, paraphrased at fourth-hand from a Tang Dynasty Chinese poem, to events three decades later. Moreover, ‘Ewigkeit is one of the oldest clichés of German Romanticism. Confronted with such a wild hermeneutical leap, the reader has a revelation too: the book should not be called Why Mahler?, a question which answers itself, but rather, My Mahler.’

The construction of Mahler as Jewish genius is a fascinating case study of the social identity processes at work among a subset of the Jewish intellectuals. From a group strategic perspective it is the psychological complement to exaggerating anti-Semitism as a way of promoting Jewish group cohesion. It consists of three related approaches, all of which are starkly evident in Lebrecht’s latest book, and all of which are entirely predictable in accordance with social identity theory. Firstly, inflate the significance of a Jewish figure’s intellectual or artistic achievement to the point where it is held to be of ‘world changing’ magnitude. Secondly, accentuate the Jewish origins and affiliations of the figure so that that his ‘world-changing’ achievement is held to be the natural expression of his Jewish origins and identity. Lastly, portray this brilliant Jewish world-changing figure as subject to the unjust persecution of a hostile, and deeply immoral, non-Jewish outgroup (in this case the society of fin de siecle Vienna). While crude, this is a highly effective strategy and a compelling example of a type of intellectual activity which, in essence, constitutes a form of ethnic warfare.

REFERENCES

Adorno, T. (1963) ‘Centenary Address, Vienna 1960’ in Quasi una fantasia – Essays on Modern Music, Translated by Rodney Livingstone, Verso, London & New York.

Bernstein, L. (1967) “Mahler: His Time Has Come.” High Fidelity. April.

Lebrecht, N. (2010) Why Mahler? How One Man and Ten Symphonies Changed the World, Faber and Faber, London.

MacDonald, K. B. (1998/2001) The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth‑Century Intellectual and Political Movements, Westport, CT: Praeger. Revised Paperback edition, 2001, Bloomington, IN: 1stbooks Library.

ENDNOTES

1 Lebrecht, N. 2010, p. x

2MacDonald, K. 1998/2001, p. 16

3Lebrecht, N. 2010, p. 232

4Ibid. p. 132

5Bernstein, L. 1967

6Lebrecht, N. 2010, p. 9

7 Ibid. p. 20

8Ibid. p. 9

9 Ibid. p. 225

[10] Adorno, T. 1963, p. 88

11Ibid. p. 24

12 Ibid. p. 114

13 Ibid. p. 25-26

14Ibid. p. x

15Ibid. p. 155-156

16Ibid. p. 28-29

17 Ibid. p. 59-60

18Ibid. p. xi

19Ibid. p. 8-9

20 Ibid. p. 41

21 Ibid. p. 100

22 Ibid. p. 108

23Ibid. p. 41

24 Ibid. p. 95

25 Ibid. p. 133-134

26 Ibid. p. 95

27 Ibid. p. 181

28 Ibid. P. 181-182

Comments are closed.