Art in the Third Reich: 1933-1945 (Part 2)

The Archaic Postmodernity

National Socialist dignitaries devoted much energy to the promotion of German sculptors and helped them considerably in the execution of massive bas-reliefs and in the erection of monumental stone and bronze sculptures. The political goal was obvious: to bring German art as close as possible to the German people, so that any German citizen, regardless social standing, could identify himself or herself with a specific artistic achievement.

It should, therefore, come as no surprise that the German art of that time witnessed a return to classicism. Models from Antiquity and the Renaissance were to some extent adapted to the needs of National Socialist Germany. Numerous German sculptors benefited from the logistic and financial support of the political elite. Their sculptures resembled, either by form, or by composition, the works of Praxiteles or Phidias of ancient Greece, or the sculptures of Michelangelo during the Renaissance.

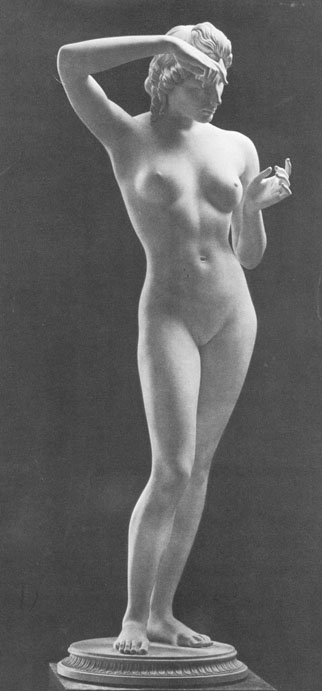

The most prominent German sculptors of that time were Arno Breker, Josef Thorak, and Fritz Klimsch, who although enjoying the significant logistical resources of the National Socialist regime, were never members of the N.S.D.A.P. Sculptures of naked women, such as “Flora” by Breker, “Girl” by Fehrle, or “Glance” by Klimsch, show excessively beautiful and geometrically pruned women who, sometimes, with their perfect bodies, with their narrow and lengthened ankles, with their well rounded and well-proportioned breasts, tire the eye of the observer.

In addition, the fact that many sculptures show naked males embracing naked females indicates that National Socialism was by no means a “conservative” or “reactionary” movement, and that Puritan Anglo-Saxon prudishness was completely alien to it. It is difficult to deny the great talent of Breker or Klimsch, even if some critics justly characterize their sculptures as workmanlike copies of classic artists.

As a young man, Breker lived in France where he was influenced by his future friend and sculptor, Aristide Maillol. After the war, many of Breker’s sculptures were destroyed by the American soldiers. In spite of his political troubles, Breker continued to work after the war making busts of his friends and protectors, (Salvador Dali, Hassan II, Louis-Ferdinand Céline, etc).

It should be noted that Breker, in the wake of the Allied occupation of Germany, was requested by the Soviets to continue his artistic career in the Soviet Union—an offer that he refused. It goes without saying that it is possible to draw certain parallels between the gigantism of the plastic art in National Socialist Germany and that of the Soviet Union (the naked Prometheus vis-à-vis the muscular and shirtless hammer-holding proletarian!). Yet the differences are again glaring: in Communist countries one could never find sculptures representing nude women and men—which confirms our thesis that Communism, although politically frightening, was primarily a prudish and conservative system. Indeed, even today, one can hardly encounter pictorial or plastic representations of embracing couples in China, Cuba, or in North Korea.

Neverthless, the sculptures of Venus or nymphs by Breker or Thorak display nothing provocative or pornographic; they never trigger sexual fantasies or erotic dreams, as is perhaps the case with the naked beauties painted by the Jewish-Italian artist Amadeo Modigliani. Upon the faces of the sculptures representing nude women made by German artists, one comes across an enigmatic and aristocratic smile and a deep sense of the tragic, which reflect, symbolically, the pessimism of a whole nation in search of its geopolitical identity. No trace can be found of female coquetry or flirtatiousness, such as one encounters among the nudes painted by the French realist, Gustave Courbet, by the Impressionist Edouard Manet, or by Paul Cézanne.

German painting of that time represents a chapter apart. Contrary to widespread ideas, “kitsch” was never part of art in National Socialist Germany. Indeed, the German National Socialist authorities adopted repressive measures against “kitsch” in the arts resembling those invoked against alleged “degenerate art.”

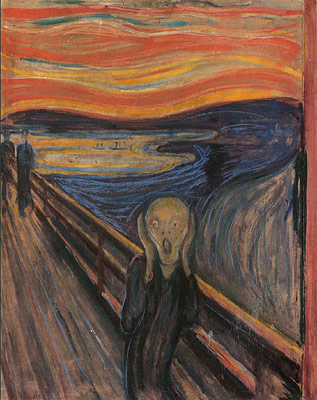

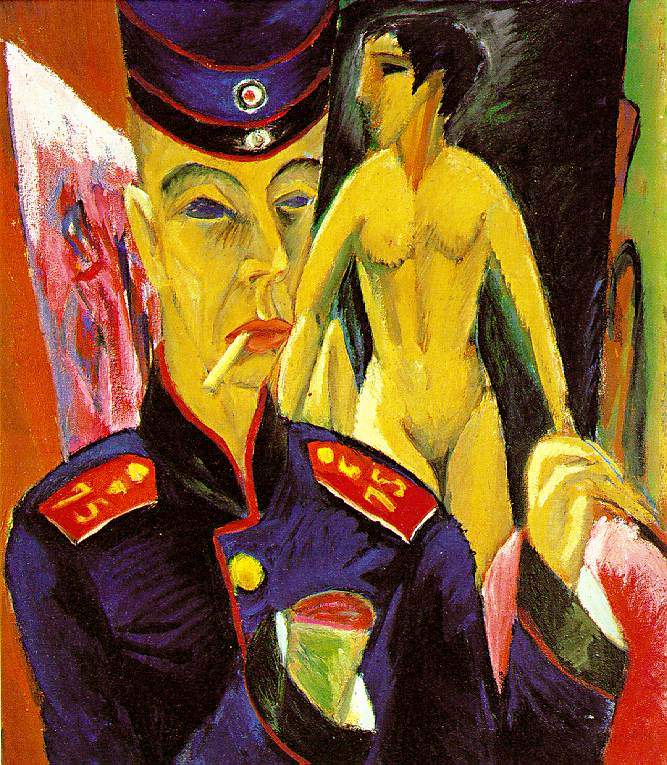

Regarding painting of that period, Germany suffered a considerable regression in the quality of its pictorial production. The early school of expressionism was abandoned and even severely repressed by the authorities as “degenerate art.” Expressionism, as opposed to Impressionism which originated in France, is paradoxically the typical feature of the German character and temperament, just as it is of other Germanic peoples (Flemings, Scandinavians).

Nevertheless, German artists of the expressionist school did not obtain the regime’s green light to exhibit their works. Schools of thought that had emerged from cultural circles such as Die Brücke or Neue Sachligkeit at the beginning of the twentieth century and had produced some of Europe’s great masters, were assailed by the National Socialist censorship.

Nevertheless, Dr. Joseph Goebbels was a great admirer of expressionist artists, and was on friendly terms with the Norwegian forerunner of expressionism, the famous painter, Edvard Munch. In December 1933, Goebbels sent a telegram to Edvard Munch on his seventieth birthday describing him as the spiritual heir of the Nordic spirit. Goebbels was also among the first to send condolences to his family on the occasion of his death in January 1944.

There were thus serious differences among NS politicians and academics regarding the nature and artistic value of expressionism, not just in its pictorial form, but also as poetic expression, as indicated by a still much admired German expressionist poet and cultural pessimist, Gottfried Benn, who was himself very close to National Socialism, and who, in his earlier days, conceived of National Socialism as first and foremost a cultural movement.

This is important because it shows that the National Socialist experiment, contrary to the later liberal-communist propaganda, was by no means a monolithic movement and that considerable personal and esthetical differences prevailed among its high ranking members and sympathizers.

The German painters, who, between 1933 and 1945, gained considerable reputation were neo-classicist portraitists and landscape painters who avoided pathetic and exaggerated compositions, and attempted to rid artistic work of every trace of the influence of Cubism and abstract art. Overall, one can sense in their paintings the revival of the taste for primitive art and a return to the Flemish masters of the fifteenth century.

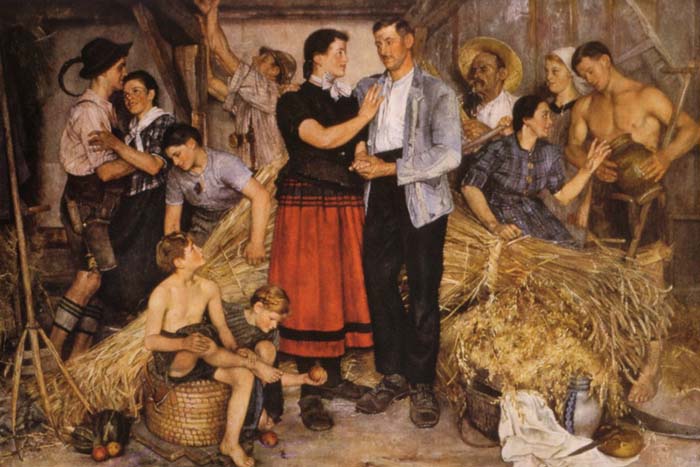

Certain parallels can again be drawn with the paintings known as “socialist-realist” in the Soviet Union and other communist countries. However, even here the difference is obvious. Whereas one can see on the paintings of Soviet artists peasants and workmen adorned with their perpetual grins and in the background a factory under construction, on the German paintings of that time seldom can one see signs of industrialization. Traces of the asphalt, chimneys spewing fumes, or factories in full gear—such as one can observe among “socialist-realist” painters (and in their titanic and apocalyptic form among the futuristic artists in fascistic Italy!), very rarely appear in the German paintings of that period. Just as one can draw a comparison between German sculptors and Soviet sculptors, one can also notice a difference between figurative art under Communism and figurative art under National Socialism.

In the art galleries of the Third Reich the scenes of handsome rural nymphs abound (Amadeus Dier, Johannes Beutner, Sepp Hilz, etc). These pastoral beauties, which can be observed on oil paintings, exude family harmony, and seem to anticipate a well-deserved rest after a hard day’s work in the cornfields. Also worth mentioning is the artist and a wood engraver, Ernst von Dombrowski, whose scenes of country life and young children playing, still win great praise from critics.

In conclusion, one can state that the German sculpture of that time, proclaims, at least as a rule, a message of racial and promethean hygiene, while the paintings of that time reveal a distinct and populist (völkisch) tendency that can hardly be misconstrued for any ideological or political speculation.

Ernst von Dombrowski (1896–1985), Scenes from peasant life in Germany (woodcuts)

Dr. Tom Sunic (websites here and here) is author, translator, former US professor in political science and a member of the Board of Directors of the American Third Position. He is the author of Homo americanus: Child of the Postmodern Age, prefaced by Kevin MacDonald (2007). The third edition of his book Against Democracy and Equality; the European New Right, prefaced by Alain de Benoist, has just been released.

Comments are closed.