The War on White Australia: A Case Study in the Culture of Critique, Part 2 of 5

The History of Judaism in Australia

Jews have been present in Australia since the beginning of European settlement. Around a dozen Jewish convicts came with the First Fleet in 1788. When the transportation of convicts to eastern Australia ended in 1853, around 800 of the 151,000 convicts to have arrived were of Jewish origin. The first free Jewish settlers arrived from Britain in 1809, and there were three subsequent waves of Jewish immigration to Australia between 1850 and 1930 – mainly German Jews arriving during the gold rushes, refugees from Tsarist Russia from 1880 to 1914, and Polish Jews after 1918. The numbers arriving with each of these waves were, however, comparatively small and Australian Jewry remained a tiny isolated outpost of world Jewry until the 1930s.[i]

Unlike in Britain where Jews were gradually emancipated through Parliamentary Acts in 1854, 1858 and 1866, in the Australian colonies they enjoyed full civil and political rights from the beginning: they acquired British nationality, voted at elections, held commissions in the local militia, were elected to municipal offices and were appointed justices of the peace.[ii] Jews were well integrated into the political and administrative structure of the colonies. Sir John Monash (1865-1931) became a general in the Australian army and was, according to Goldberg, “the only Jew in the modern era outside Israel (with the exception of Trotsky) to lead an army.”[iii] Sir Isaac Isaacs (1855-1948) became Australia’s first native-born Governor-General. In Australia under the Immigration Restriction Act of 1901 these highly assimilated Anglo-Jews were regarded as “White,” whereas Jews of middle-eastern origin were regarded as Asian and therefore barred from entry.

Jewish academic Jon Stratton points out that the high level of assimilation of Anglo-Australian Jewry was reflected in the relatively high levels of intermarriage through the 19th century and the first half of the 20th. In 1911, some 27 per cent of Jewish husbands in Australia had non-Jewish wives and 13 per cent of Jewish wives had non-Jewish husbands. In 1921 these figures had increased to 29 per cent and 16 per cent respectively. However, by the 1991 census there had been a decline to an overall rate of 10-15 per cent.[iv] Stratton notes that “the acceptance of intermarriage signifies a lack of racial difference. Jews were thus caught on the horns of a dilemma. If they were accepted as marriage partners by gentiles this was a crucial step in the process of national assimilation but, in marrying gentiles, they destroyed the endogamous basis of Jewish particularity.”[v] This is an acknowledgment of the essentially incompatibility of Judaism and Western culture in the tendency of individualistic Western cultures to break down Jewish cohesiveness.

The Ashkenazi Jews who migrated from central and eastern Europe between 1930 and 1950 created an identity crisis within the established Anglo-Jewish community. In their political radicalism, avowed Zionism and intense ethnocentrism, they differed greatly from the Anglo-Australian Jews. The new migrants had the effect of making the Anglo-Jews more visible as a group through their association with the new European Jews. They also provoked hostility from significant sections of the Australian community, who correctly sensed that the psychologically intense and politically radical newcomers posed a fundamental threat to their nation.

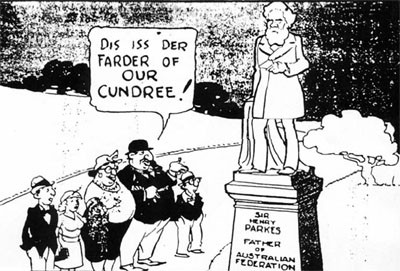

In 1933 there were still only 23,000 Jews in Australia. Between 1938 and 1961 this number almost trebled to 61,000. The 2011 census indicated a Jewish population of 97,335 out of an overall population of 23 million.[vi] Currently ranking ninth in worldwide Jewish communities, the Jewish historian Suzanne Rutland laments that today Jews only “constitute only 0.5 per cent of the overall population” and ascribes this to “the hostility that was expressed towards Jewish immigration” in the 1930s and 1940s. From Hitler’s assumption of power in 1933 Jewish representatives in London and Australia lobbied the Australian government to allow more Jews to settle, but until 1936 such requests were met with a negative response. In that year the Assistant Secretary of the Ministry of the Interior, T.H. Garrett, opined that “Jews as a class are not desirable immigrants for the reason that they do not assimilate; generally speaking, they preserve their identity as Jews.”[vii]

Following the German Anschluss with Austria in 1938 the Jewish refugee problem worsened as a further 180,000 Jews came under National Socialist rule. President Roosevelt convened an international conference to discuss the refugee crisis. Held in Evian, France in June 1938, thirty-eight countries, including Australia, were represented. The position of the Australian government, which announced that it would not liberalize its immigration policy from an annual quota of 5,000 was mirrored by the other participating nations. Only the Dominican Republic altered its immigration laws to increase the flow of Jewish immigrants. Australia’s delegate, Thomas W. White, expressed the popular view when he declared that “as we have no real racial problem, we are not desirous of importing one by encouraging any scheme of large scale foreign migration.”[viii]

Supporting the Australian government’s stance, the influential publication The Bulletin argued that “Australia cannot be expected to imperil its existence or to receive vast numbers of alien refugees for the gratification of German Jews, New York politicians and editors, and is not going to do it, either.”[ix] Referring to Jewish immigration, the weekly Truth asserted in 1938 that “As a racial unit they are a menace to our nationhood and standards.”[x] A similar view was reflected by one concerned citizen who wrote to the Minister for External Affairs in 1938 insisting that the Jewish immigrant was: “unBritish in his dealings, he is unscrupulous, unprincipled except towards his kith and kin – he’ll stop at nothing in his mercenary and spineless tactics to gain his own ends. … God help us if something is not done to block these scurrilous and designing people from gaining a stranglehold which all the laws imaginable will not prevent.”[xi]

When the Australian government announced in December 1938 that 15,000 more refugees would be admitted over the following three years, the Catholic Advocate warned that:

If the present policy of admitting large numbers of Jewish immigrants is continued, we are likely to be confronted by a rapid increase in anti-Semitism. … The Jews are not simply an international religious body like the Catholics: they are a nation with well-marked characteristics, both mental and physical, with their own virtues, vices and talents, and with their peculiar loyalties. … It is the sense of this difference which has caused friction between the Jew and his hosts throughout the ages, and which has constantly brought tragedy to the Jews.[xii]

Another leading voice of opposition to Jewish immigration to Australia around this time was the patriotic Australia First movement which was inaugurated by the Sydney businessman W.J. Miles. When the movement was constituted in 1941 it issued a manifesto which declared that: “The Jewish practice of racial segregation and exclusiveness makes the assimilation of Jews into the Australian community an impossibility; … people who are determined to remain racially aloof should never be admitted in large numbers to Australia.”[xiii] Following Miles’ death in 1942, the Australia First movement came under the leadership of P.R. Stephensen, an Australian cultural nationalist, literary figure and Rhodes Scholar. In an article in the Australian Quarterly in 1940, Stephensen observed that “Wherever Jews wander they take not only Semitism, but also anti-Semitism with them. … As has been said elsewhere, ‘they chose to be Chosen, and must take the consequences.’ … It is solely because the Jews insist on preserving their racial identity that they are a problem in every country in which they settle.”[xiv]

Stephensen noted that Jews always exerted disproportionate influence in the countries they resided in because, unlike their neighbors, they are highly-organized, which “guarantees their survival and prosperity wherever they go” and “undoubtedly supplies the inspiration and model for Communist Party organization in all countries, including Russia and Australia.”[xv] Given that Stephensen started his political life as a founding member of the Australian Communist Party, he was well placed to comment on the significance of Jewish influence within Communist Party organizations. The Communist Party of Australia itself was to be dominated throughout the Cold War period by Jews like Laurie Aarons, its secretary between 1965 and 1976.

Deeply concerned at increasing Jewish power and influence in Australia, Stephensen declared:

The answer to Semitism is anti-Semitism; and when Jews gain too many advantages for themselves, by their practice of self-segregation, they invariably find (and surely should expect to find!) that the majority of non-Jews will resent, and eventually will curb, the privileges which the Jews have won for themselves by concerted sectional action. That is what will inevitably occur in Australia sooner or later, if a large colony of self-segregating Jews is allowed now to establish itself in our community.[xvi]

For Stephensen, Jewish ethnocentrism and endogamy were at the heart of the Jewish problem, and the solution to this problem was simple:

It is well known that there are many Jews who are good citizens, honest and cultured, despite the reputation of the generality of their kind of being financially “tricky”, unscrupulous, and parasitical. That there are intellectual and sensitive Jews is also as well-known as that there are many “Flash Yids” who degrade and debase public culture. No case can be made against Jews generally, except … that their insistence on racial self-segregation is anti-social, considered from the point of view of the community as a whole. We cannot concede to them in Australia a right which, if conceded in perpetuity to other types of immigrant … would lead to the sectionalizing of the community and its disunification. … The remedy is that the Jewish Race should abolish itself, by becoming absorbed in the common stream of mankind. [Otherwise] we others, who are so strictly excluded from the Jewish community, have at least a reciprocal right to exclude them from ours.[xvii]

In retrospect, Stephensen accurately predicted the fragmentation of Australian society that was to occur under the malign influence of multiculturalism – a Jewish-originated and promoted ideology designed to preserve Jewish particularism, while demographically, politically and culturally weakening the majority White Australian population. In the Jewish promotion of racial and cultural “pluralism” in Australia, Jews have, exactly as Stephensen predicted, caused the “sectionalizing” and “disunification” of the Australian community.

In 1939, Stephensen successfully sued a Communist Party newspaper for libel when it accused him of “being a propagandist for the Nazis.” When asked in court whether, through his writings, he had “sedulously endeavoured to stir up anti-Semitic feeling in this country” he replied: “Not as you put it; but as a Gentile, I am opposed to Jewish influences in Australia.”[xviii] Stephensen was the editor of the Australia First publication Publicist which published articles by a range of distinguished writers who were forthright in their views about the dangers of substantial levels of Jewish immigration. One of these contributors, Rex Williams, wrote that

Australians would be silly to ignore the warnings of 5000 years of Jewish history – a history of penetration by guile, followed by expulsion by force from almost every land in which Jews have settled. It is no use blaming gentiles for “persecuting” Jews! The Jews, by their malpractices, ask for it – and get it. They are never loyal to any country in which they settle: they are loyal only to their “international” and “non-national” Race. And that is how they get themselves into trouble, in Australia, as everywhere else.[xix]

Another leading voice of opposition to Jewish immigration was Henry Baynton Gullet, the Liberal member for the electorate of Henty in Victoria. In 1947, in a letter to the Melbourne Argus he observed that the Jews “are European neither by race, standards, nor culture… In 2000 years no one but Britain has been successfully able to absorb them, and for the most part they owe loyalty and allegiance to none… They secured a stranglehold on Germany after the last war during the inflation period, and in very large part, brought upon themselves the persecution which they subsequently suffered… These are the people who at the direction of international Jewish organisations, are being foisted upon us who are to become the dumping ground for the world’s unabsorbable.” Gullet concluded his letter by declaring that, “The arrival of additional Jews is nothing less than the beginning of a national tragedy and a piece of the grossest deception of Parliament and the people by the Minister for Immigration.”[xx]

Another group opposed to Jewish immigration was the Returned Services League (RSL), whose president in New South Wales, Ken Bolton, called for the immediate and total cessation of Jewish immigration to Australia in the national interest. In 1946 Bolton declared: “let us not beat about the bush. … they are German Jews of the same ilk as those who have come before.” The president of the Australian Natives Association, P.J. Lynch, stated in 1947 that Australia must not become a “dumping ground for European refuse now causing trouble in Palestine … as Jews in Palestine were murdering and flogging British subjects.” Lynch, like many Australians, was outraged by the terrorist attacks on the British Mandatory forces in Palestine by Zionist terrorists. These included the assassination of Lord Moyne in 1944, the dynamiting of the King David Hotel in July 1946, the flogging of a British officer and sergeants, the kidnapping of a judge in December 1946, and the hanging of two British sergeants by the Irgun in July 1947. As a result of the anger generated by these events, and the backlash suffered by the Chifley Labor government for accepting a quota of Jewish refugees in 1945-46, restrictions on Jewish immigration were introduced in 1947 and maintained until 1952.[xxi]

Jewish motivations for opposing the White Australia policy

Jewish interest in the liberalization of Australia’s immigration policies thus stemmed, at least initially, from a desire to provide sanctuary for Jews fleeing Europe. Indeed memories of the Australian government’s opposition to expanded Jewish immigration prior to and immediately after World War Two was undoubtedly a prime motivating factor behind the Jewish campaign to end the racially-restrictive White Australia policy and establish support for multiculturalism as a central pillar of Australian government policy.

Furthermore, these memories continue to drive Jewish ethno-political activism in contemporary Australia. For the prominent Jewish intellectual (and self-appointed moral conscience of the Australian nation) Professor Robert Manne, “One of the most powerful stories to emerge from the Holocaust, which meant a lot to me, concerned the unwillingness of almost all the Western nations to offer homes to significant numbers of Jews who fled from Germany in the 1930s. The defence of refugees has been for me and for many post-Holocaust Jews, a permanent feature of the political landscape.”[xxii]

The disgraced former judge and leading representative of the Australian Jewish community, Marcus Einfeld, expressed a similar sentiment, declaring that “Australia has long held the sentiment that it offers a good quality of life to those within its borders, free of problems and conflicts. It seems that opening its doors to save thousands of Jews from wholesale murder in the approaching Nazi storm was thought likely to bring unwanted problems and imbalance and to disturb the peaceful Australian lifestyle.”[xxiii] Einfeld was especially angry that even after the war “protests from trade unions and the conservative side of politics amongst others, forced the government of the day to limit the number of Jews on any one ship to 25 per cent, thus leaving many to wallow in camps in Europe until the birth of Israel or the willingness of other countries to take them.”[xxiv]

In response to these views, one is prompted to observe that the same rationale for restricting Jewish immigration to Australia in the 1930s and 1940s (i.e. national and ethnic self-interest) has been, and continues to be, invoked by Israel and its supporters to justify its racially-restrictive immigration policy, and for its recent deportation of “enemy infiltrators” from Africa. Jewish intellectuals hypocritically condemn the Australians of the 1930s and 1940s for having refused to subordinate their group interests to those of a hostile out-group – when Jews and the state of Israel resolutely refuse to do the same. Only European-derived peoples have opened their doors to the other peoples of the world and now stand in danger of losing control of territory occupied for hundreds of years, as in Australia, Canada and the United States, or, in the case of Europe itself, many thousand years.

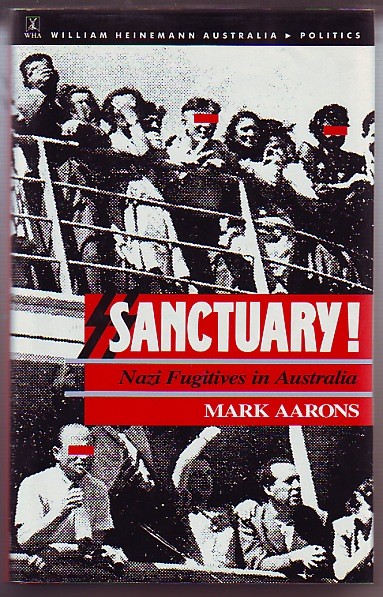

Another source of Jewish hostility to White Australia was their belief that “Nazi collaborators” and “war criminals” were given sanctuary by the Australian government. 200,000 European displaced persons were accepted into Australia between 1947 and 1950, including from nations that had been German allies during the war. According to the Jewish historian Suzanne Rutland the Australian selection procedures were inadequate, with the focus on excluding “enemy aliens” such as Germans and Italians “rather than on Eastern European collaborators, many of whom had joined the Waffen SS.”[xxvi] She claims that the small number of Jewish displaced persons in migrant camps “often experienced anti-Semitism, and in some cases even recognized a camp guard.”

The “Jewish Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism” was formed to follow up these claims. Rutland claims that “When data of Nazi and anti-Semitic activities in the migrant camps was presented to the Department of Immigration, it was disregarded because of the communist links of the Council to Combat Fascism and Anti-Semitism” and because the government believed the charges were “activated by religious or national bias.”[xxvii] Interestingly, Jewish leaders have never expressed any corresponding concern that Jewish communist criminals from the former USSR and the Eastern bloc were able to freely migrate to Israel and the West following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

Jewish organizations in Australia lobbied energetically for Germans to be excluded from the Australian post-war migrant intake. In 1950 the Australian Jewish Council issued a booklet entitled German and Volks Migration Will Flood Australia With Nazis. It depicted an arrogant army officer as the type of German migrant Australia would be likely to receive.

The Nazi Germans who are likely to come to this country will be bad migrants and … will endanger the living standards of the people. … There are certain people in Australia who are anxious to abolish the 40 hour week, and destroy the independent trade union movement. How much better can this be done with a horde of Nazi migrants accustomed to working a 48 hour week and hostile to trade unionism?[xxviii]

White Australia is widely regarded by Jews (together with the United States, Canada and Britain) as having been an accessory to the “Holocaust” by limiting the number of Jewish refugees it was willing to accept from Europe, and also by accepting thousands of “Nazi war criminals” as migrants after the war. Given this perception, it will come as no surprise that Jewish ethno-political activism was fundamental to ending White Australia and in establishing support for ‘multiculturalism’ as a central pillar of Australian government policy.

An added stimulus was the sense of Jewish insecurity that accompanied the 1967 and the 1973 wars between Israel and the Arabs. Throughout the Jewish world there was a spontaneous and immediate response to the 1967 crisis, and the Australian Jewish community was no exception. In Melbourne, 7,000 out of a community of 34,000 attended a public rally called at the outbreak of the fighting, and 2,500 attended a youth rally in the same week. In Sydney, over 6,000 people crowded into the Central Synagogue and its surrounds. In both cities, hundreds of Jewish youth volunteered to go fight for Israel. A 1967 study of Melbourne Jewry found that most people interviewed reacted with deep emotional upset, staying glued to the news from Israel, and seeking social contacts with family members and other Jews.[xxix] Australian Jews who were more “assimilated” or not active in communal organizations were equally affected. These feelings were reinforced by the Yom Kippur war of 1973. Professor Robert Manne’s response to the 1967 war was typical:

My most intense political feelings about Israel occurred when I was in my second year of university, at the time the war between Israel and the Arab world in June 1967. Shortly after the war broke out I attended a large meeting somewhere near Albert Park Lake in Melbourne. At the time no one knew whether or not Israel would survive. Neither before nor since have I experienced such an atmosphere charged with political emotion. This was the only time in my life when I felt the visceral power of nationalism which took hold of me and of much of the audience of mainly post-Holocaust young Jews. Like many others I was determined to go to Israel to fight. Twenty years after the Holocaust, I felt that I could not remain in the safety of Australia while the Jewish people in Israel were destroyed.[xxx]

This was the intellectual and political context for Jewish ethno-political activism in Australia (and throughout the Western world) between 1967 and 1973. This activism centered around three main objectives: to ensure the ongoing existence of Israel as an ethnically homogeneous Jewish state; to ensure the safety of diaspora Jewry by reforming Western immigration policies to promote racial and ethnic diversity (high levels of White racial homogeneity being regarded as potentially dangerous to Jews); and finally, to ensure the continuation of Jewish ethnic separatism and endogamy (and counter assimilation) in the West through promoting the official adoption of “multiculturalism.” This unanimity of opinion among Australian Jews with regard to these key objectives continues through to the present day. Historian William D. Rubinstein notes that

Politically, the Jewish community is strongly united on a limited number of goals on which there is consensus or near consensus, especially support for Israel, fighting anti-Semitism and endorsing multiculturalism, and stemming assimilation through Jewish day-school education. It has been fairly successful in achieving these goals, probably because it is unusually united and also because the quality of its secular leadership has been very high. The contemporary world Jewish situation, formed chiefly by the Holocaust and the re-emergence of the state of Israel, has produced a near universal consensus on similar goals through the Jewish world.[xxxi]

The “Holocaust” and Zionism continue to be “the magnetic poles for the compass of Australian Jewish identity.”[xxxii] Anti-Semitism and intermarriage are still regarded as the two most ominous threats to Diaspora Jews. The liberalization of Western immigration policies and the institution of state-sponsored “multiculturalism” throughout the West are almost universally regarded by Jews as the most effective ways to counteract these threats. The next part of this essay will look at the crucial role of the leading Australian Jewish activist Walter Lippmann in establishing multiculturalism as a central pillar of Australian government policy.

REFERENCES

Einfeld, M. (2006) ‘We Too Have Been Strangers: Jews and the Refugee Struggle,’ In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski, Black Inc., Melbourne. pp. 305-315.

Fagenblat, M., Landau, M. & Wolski, N. (2006) ‘Will the Centre Hold?,’ In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski, Black Inc., Melbourne. pp. 3-16.

Goldberg, D. (2006) ‘After 9/11: The Psyche of Australian Jews,’ In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski, Black Inc., Melbourne. pp. 140-152.

Manne, R. (2006) ‘The Holocaust and Political Identity: A Personal Account,’ In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski, Black Inc., Melbourne. pp. 46-55.

MacDonald, K. B. (1998/2001) The Culture of Critique: An Evolutionary Analysis of Jewish Involvement in Twentieth‑Century Intellectual and Political Movements, Westport, CT: Praeger. Revised Paperback edition, 2001, Bloomington, IN: 1stbooks Library.

Rubinstein, H.L. (1991) The Jews in Australia – A Thematic History, Volume 1: 1788-1945, William Heinemann, Melbourne.

Rubinstein, W.D. (1991) The Jews in Australia – A Thematic History, Volume 2: 1945 to the Present, William Heinemann, Melbourne.

Rubinstein, W.D. (1995) Judaism in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra.

Rutland, S.D. (2005) The Jews in Australia, Cambridge University Press, Melbourne.

Rutland, S. (2006) ‘Why Does Australian Jewish History Matter?,’ In: New Under the Sun – Jewish Australians on Religion, Politics & Culture, Ed. Michael Fagenblat, Melanie Landau & Nathan Wolski, Black Inc., Melbourne. pp. 293-304.

Stratton, J. (2000) Coming Out Jewish – Constructing Ambivalent Identities, Routledge, London.

Tavan, G. (2005) The long, slow death of White Australia, Scribe Publications, Melbourne.

[i] Rutland p. 22

[ii] Stratton p. 201

[iii] Goldberg p. 151

[iv] Stratton p. 207

[v] Ibid.

[vi] Rutland p. 51

[vii] Stratton p. 208

[viii] Rutland p. 57

[ix] H.L. Rubinstein p. 507

[x] Stratton p. 209

[xi] H.L. Rubinstein p. 503

[xii] Ibid. p. 505-506

[xiii] Ibid. p. 496

[xiv] Ibid.

[xv] Ibid.

[xvi] Ibid.

[xvii] Ibid. p. 496-497

[xviii] Ibid. p. 497

[xix] Ibid. p. 498

[xx] W.D Rubinstein p. 386

[xxi] Tavan p. 50

[xxii] Manne p. 53

[xxiii] Einfeld p. 307

[xxiv] Ibid. p. 310

[xxvi] Rutland p. 72

[xxvii] Ibid. p. 73

[xxviii] W.D Rubinstein p. 413

[xxix] Rutland p. 87

[xxx] Manne p. 50

[xxxi] Rubinstein 195 p. 7

[xxxii] Fagenblat et al. p. 6

Comments are closed.