Vanishing Anglo-Saxons: Jared Taylor’s White Identity and the Crisis “We” Face, Part 2

The Sin of Americanism

From birth, the American Adam was stained by the original sin of the American Republic. Loyalist writers, many of whom were royal officials or Anglican clergymen, warned that the colonial rebellion was spawning an embryonic system of anarcho-tyranny. They saw clearly that the revolutionary republic undermined “deference for established leaders and institutions.” By playing upon popular passions, radical leaders reduced the colonies to anarchy, ripe for a novel “democratic tyranny” controlled, behind the scenes, by an ambitious, avaricious, and utterly self-interested elite of so-called Patriots.

The Loyalists knew that such a regime was bound, sooner or later, to end in tears. Unfortunately, American White nationalists still invest their hopes for the future in the Patriot tradition of Constitutional Republicanism. Racial realists such as Jared Taylor also struggle to endow the cult of the Constitution with an explicitly White identity.

Indeed, almost all of the many WASPs on the alternative Right—for example, Peter Brimelow, Richard Spencer, and Greg Johnson—hope “to salvage as much as possible from the shipwreck of their great republic.” But they owe it to their Anglo-Saxon ancestors to recognize at long last that the Loyalists were right to oppose rebel colonists while defending the unity of the British race.

It is now obvious that the perpetual American Revolution has been an ongoing catastrophe for the Anglo-Saxon race. More than twenty years ago, Brimelow warned English Canadians that the “patriot game” is up; that they should unite with their co-ethnics kin south of the 49th parallel. He would do well to adapt that advice to the parlous prospects now facing American WASPs, standing alone, unorganized, and leaderless, in a globalized, multi-racial Empire.

Specifically, he should help to rejuvenate the British race patriotism that was second nature to the United Empire Loyalists. It was just such ancestral loyalty to throne and altar that led the Loyalists to settle in Canada after being driven, in their tens of thousands, out of the victorious and vengeful republic.

American patriotism, by contrast, was based not on race but on the American Creed, the Constitution and the Manifest Destiny of the aggressively expansionist Republic. Ironically, it was the founding race of Anglo-Saxon Protestants who embraced most fervently the constitutional faith that eventually dispossessed their posterity in favour of the teeming Others of the Third World.

Now that the Constitution has been turned into a mere thing of wax which the powers-that-be cynically shape in whatever form they please, American WASPs are bereft of a coherent and credible civic identity. Nor do they have even the residual constitutional ties to their kith and kin in other “Anglo-Saxon countries”—still symbolized by shared loyalty to the British monarchy—that bound the “old White Commonwealth” together.

The Necessity of Britishness

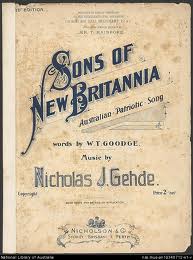

Jared Taylor visited Australia recently. While there, he toured several Anglo-Saxon sacred sites in Sydney and Parramatta. Taylor investigated modern Australia’s inauspicious origins in a British penal colony in New South Wales. He also witnessed the massive extent of recent Third World colonization in Australian cities.

The ancestors of the Anglo-Australians that Taylor met in Sydney first came to this country just as the US Constitution was being ratified in the various States of the proposed Union. For over two centuries now, Anglo-Australians have been a constituent part of the now bowed but not beaten British race.

Taylor has just seen a magnificent city built on the other side of the world by many generations of his Anglo-Saxon Protestant kinfolk (with some help from Irish Catholics). The experience should help him to understand what one Australian historian has called “the necessity of Britishness.” American WASPs, generally, can rediscover an unexpected stock of spiritual and cultural capital in their ancestral links to the people of the old British dominions such as Australia, Canada, and New Zealand.

In the century to come, the resources available to the British diaspora will provide a fertile seed-bed for trade, commerce, and intercourse within a global network of Anglo-Saxon tribes. By comparison, the modern nation-state offers no more than a specious simulacrum of collective identity. In erstwhile “Anglo-Saxon countries,” the official cult of the Other poisons the organic union of nation and state.

The rebirth of an Anglo-Saxon racial consciousness will be a transnational phenomenon. The global reach of the Anglo-Saxon diaspora will be an invaluable resource for otherwise isolated and ineffectual WASP communities. In particular, the survival of British institutions such as the monarchy and the Anglican Church leaves Anglo-Saxon Protestants in Australia, Canada, and New Zealand with an advantage not available to their American cousins.

Unfortunately, Australia, like the USA, is being colonized by the Third World. But, arguably, Anglo-Australians are better equipped than American WASPs to resist that invasion. They still retain access to the repertoire of British myths and symbols that played such a crucial role in the creation of Australian nationality. It may yet be possible for Anglo-Australian patriots to regenerate the foundation myth of “a new Britannia” in the antipodes.

In the federation era, “Australian nationalists did not choose British origins for their nation; that was an inescapable fact of history. They did choose to emphasise British ethnicity as a keystone of national cohesion.” According to Russell McGregor, they promoted an “essentialised, ethnicised” form of nationalism.

In other words, the same blood that “congealed the Australian people into a single nation…also connected them to the British parent.” The Premier of Victoria insisted in 1899 that the Australasian colonies “were all cradled by the great Mother of the British Race.” At the turn of the twentieth century, references to “the crimson thread of kinship” binding Australians to the mother country were a staple of political rhetoric.

But Australian ethnicity “was more than a matter of blood”: “Britishness was the source of the heritage, history, culture and symbols that made Australia heir to a glorious past.” McGregor demonstrates that the “myths and symbols that resonated most deeply and meaningfully among the Australian people were Britannic myths and memories. These enabled Australians to transcend local or parochial loyalties, to conceive themselves as a national community with deep temporal roots.”

It is indisputable, therefore, that the Britannic heritage was “an essential source of sustenance and strength to Australian nationalism.” Not surprisingly, therefore, the so-called White Australia Policy laid down in the very first Act of the Commonwealth parliament “was founded on the assumption that ethnic unity provided the foundation-stone of both national cohesion and political democracy.”

And, as more than one Member of Parliament observed, White Australia “really means a British Australia.” Of course, White non-Britishers were admitted but only “on the understanding that they would readily assimilate, biologically as well as culturally, into the British-Australian nation.”

The Decline of Britishness

As early as 1923, Myra Willard’s analysis of the White Australia Policy warned that the “continued immigration of certain European peoples very dissimilar to Australians would have the same effect” as immigration from Asia. Unfortunately, the “populate or perish” mentality that took hold among the political class after the Second World War was the thin edge of the wedge which eventually whittled away the British core of Australian national identity.

And so it happened that the large-scale post-war influx of Italians and Greeks, for example, was the first step towards the decline of the Anglo-Saxon Protestant ascendancy in Australian politics and culture.

Well into the Sixties, however, both the monarchy and the overwhelmingly Anglo-Saxon Anglican Church—still known in Australia as the Church of England—worked to reinforce the British roots of Australian national identity. Both institutions were joined at the hip. The British monarchy was integral to Anglican thought and practice in Australia. For centuries, the monarch had been supreme governor of the Church and on accession took an oath to preserve its doctrines.

According to church historian, Brian Fletcher, “Anglicans believed that the monarchy possessed divine attributes.” They “took pride in the fact that at the apex of government stood one of their own faith—a claim no other denomination could make.” From Federation in 1901 until 1962, therefore, the Anglican Church helped keep alive in Australia cultural and other values that derived from Britain. Indeed, “it endowed empire, monarchy, and race with a religious sanction.”

By the Sixties, however, Anglicans responded to the radical nationalist intellectual movement that drove a wedge between the Britannic heritage and Australian identity, between ethnic and civic nationalism. The rise of “ocker nationalism” was assisted greatly by the Australia’s geopolitical shift from the British to the American sphere of influence. Some historians point to Britain’s entry into the Common Market as the decisive moment in such efforts to draw Australian national identity away from “the British embrace.”

At the same time, successive waves of non-British European migration cleared the path for the gradual abolition of the White Australia Policy in the late Sixties and early Seventies. Within an astonishingly brief time, a multi-racial society was established in the nation’s largest cities.

Fletcher points out that “the Anglo-Saxon ascendancy lost ground not only to post-war migrants but also to the large Irish minority whose social status rose.” Interestingly, in the Federation era, McGregor notes that the Irish had been “resistant to comprehensive Anglicisation” while remaining “generally receptive to the myth of Britishness.” But since the Sixties, the Irish have played a militant role in the rise of the Australian republican movement.

In 1999 a referendum was held to determine whether Australia should sever its constitutional ties to the British monarchy in order to become a republic. Leftists were pleased to see that non-British migrants joined Irish-Australians in lending disproportionate support to the Yes vote. Fully forty-five percent of the vote favoured a republic.

By that time, of course, the Anglican Church no longer viewed the survival of British-Australia as a vital theological issue. Indeed, by the Eighties, Anglican leaders were determined to avoid the perceived “dangers of remaining tied too exclusively to their heritage.” Accordingly, Bishop Reid of Sydney expressed fears in 1983 that “in another generation Anglicans will be seen as an Anglo-Saxon sect.”

Rather than become an ethno-religious ghetto for “White Australian Anglo-Saxon Anglicans,” the Anglican church chose to fashion “a new and dynamic national church” open to people of any and all races and ethnicities.

British-Australia is clearly down but it has not yet been counted out. Both the monarchy and the church can once again help to revive the fortunes of the Anglo-Saxon race.

A Postmodern Pan-Angle Confederation?

It has taken Anglo-Saxon Protestants hundreds of years to dig themselves into the black hole now inhabited by the invisible race. It will take at least a century to climb out again. During the New Dark Age looming ahead of us, the political, cultural, and economic landscape of the world will be transformed utterly.

The gargantuan, impossibly complex structures of corporate neo-communism are likely to fail. In the long emergency which follows any such collapse, the search for resilient communities will foster a new tribalism.

The monarchy and the church—which together created the English nation over a thousand years ago—will be the essential medium for the postmodern rebirth of the Anglo-Saxon race. Anglo-Saxon Protestants must shed the bad habit of looking to the corporate welfare state to preserve and protect their collective identity. The modern state has been captured by the cosmopolitan elites presiding over the globalist system of corporate neo-communism.

Sooner or later, the time will come when Anglo-Saxon Protestants in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and even the UK recognize that their collective interests can best be served by detaching or disestablishing both the monarchy and the church from the state apparatus.

Anglo-Saxon Protestants in the old British dominions need not fear the advent of republican constitutions. The British monarch will remain the head of the Anglican Church throughout the diaspora. Outside and apart from the state, a Christian King will serve as defender of the ancient blood faith of the Anglo-Saxon race. A postmodern confederation of Anglo-Saxon Protestant tribes acknowledging allegiance to a new-modelled British monarchy will become the stateless incarnation of the Pan-Angle union imagined by men such as Sinclair Kennedy in the early twentieth century.

According to Montesquieu, honour is the generative principle of monarchy. By honouring selected subjects, by conferring upon them ranks, titles, and pre-eminences denied to others not so favoured, a king can regenerate an Anglo-Saxon aristocracy. In an earlier book, I have tried to show how an aristocracy might thus be reinvented in the least expected area of corporate governance.

It may seem far-fetched to suggest that through the Anglican Church in England, Australia, and even in America the Holy Spirit will once again irradiate the Anglo-Saxon Volksgeist. But Anglo-Saxon Christians of the early twentieth century certainly never expected to see their island race laid low by the dregs of the Third World now flooding into their homelands.

Who is to say that we are not on the cusp of a new Golden Age in which Anglo-Saxon Christian tribes unite to serve the King while the King serves God? The rebirth of Christian nationalism may well become an adaptive response to the crisis facing Anglo-Saxon Protestants over the next century.

Anglo-Saxon Christian Nationalism

White nationalists frequently blame Christianity for the universalist drive to transcend the biocultural realities of race and ethnicity. But that is not the whole story.

No one can deny, of course, that “early Christianity was committed to universal, values,” if only because it sought very consciously to transcend Jewish national particularism But, as Adrian Hastings points out, the spiritual vision of a heavenly, new Jerusalem “could not negate an equally pervasive quality of incarnatedness, rather it reinforced it.” As one second century writer put it, the body, the flesh, might “hate the soul. … All the same the soul loves the flesh.”

We also know, Hastings adds, that “Pentecost thus established a program which was both universal and particularist, providing full justification for translation of the scriptures and rites of the Church into any and every language.”

This program was in accordance with Christ’s Great Commission (Matthew 28:19 NKJV) “to go and make disciples of all nations.” In the course of his own mission to the gentiles, Paul explained that God made “every nation of men to dwell on all the face of the earth, and has determined their preappointed times and the boundaries of their dwellings, so that they should seek the Lord, in the hope that they might grope for Him and find Him, though He is not far from each of us” (Acts 17: 26-27, NKJV).

Historians have demonstrated that the “evolution of English and other national identities in the Middle Ages” owed an enormous “debt to specifically biblical and Christian influences.” The strong particularist loyalties which came to dominate Europe challenged “the universalist vision of Christian society which had hitherto shaped” the European mind, but they “were themselves a product of Christianity.”

Hastings affirms that the “forces within Christianity and society encouraging the rise of nations and nationalism were at work within every ecclesiastical tradition and almost every part of Europe.” For much of the twentieth century, however, the forces of Christian universalism rose into prominence once again. In the wake of two destructive world wars, both Catholics and mainline Protestants began to view the forces of nationalism as a blight on Christian civilization (see here and here).

Hastings concludes, however, that “a false universalism is now an even greater threat, a succumbing to the globalization, economic, cultural, and political, sweeping the world under the pressure of capitalism and American military dominance.” Effective resistance to the crassly commercial cosmopolitanism of corporate neo-communism will emerge when the particularistic Volksgeist of Christian nations incarnates the ecumenical spirit of the holy, catholic, and apostolic church, each in its own manner.

Marooned in their propositional republic, American WASPs are fixated on the universalistic ideal of Christian charity. Such pathological altruism has suppressed the particularistic principle of honour—a traditional manifestation of the love of God found deep in the heart of the European nobility. The divinely-ordained mission of both the British monarchy and the Anglican church, therefore, must be to promote a Christian way of life grounded in the charity of honour.

Conclusion

A chain is only as strong as its weakest link. Partly-inbred and relatively large in numbers WASPs may be, but they are also a hopelessly dysfunctional extended family. Without a healthy racial consciousness to prevent further self-harm, dishonourable WASPs remain a threat to the restored unity of European Christendom.

Anglo-Saxon Protestant men of honour will not remain an invisible race. A postmodern Christian ethno-theology will foster the spiritual rebirth, or palingenesis, of the Anglo-Saxon race. Nowhere is that regenerative mission more urgent than amidst the decaying ruins of the American Republic.

A new age will have dawned when Jared Taylor’s Anglo-American kin-folk join Anglo-Australians to sing “God Save the King.”

Andrew Fraser was born in Canada and educated there and in the USA before moving to Australia where he taught law at Macquarie University in Sydney. He is the author of The WASP Question: An Essay on the Biocultural Evolution, Present Predicament, and Future Prospects of the Invisible Race (Arktos, 2011)

Comments are closed.