Ben Zygier and Israeli’s Abuse of Australian Passports

A fascinating article recently appeared in the Fairfax newspapers in Australia concerning the late Melbourne-born Mossad agent Ben Zygier. The result of a joint investigation by Fairfax in Australia and Germany’s Der Spiegel magazine, the article, entitled “The life and death of Prisoner X,” outlines the sequence of events which led to Zygier’s arrest, imprisonment, and ultimate suicide in an Israeli prison. In the words of the author, Jason Koutsoukis, Ben Zygier “was responsible for one of the most serious security breaches in Israeli history, a breach that led directly to the imprisonment of two of Israel’s most prized Lebanese informants.” While an interesting story in its own right, the Zygier case also highlights the perils of allowing Australian Jews to have joint Australian-Israeli citizenship: in particular, it reveals how the Mossad deliberately recruit these dual nationals to use their Australian passports as cover for their operations – including for assassinations.

The general tone of the article is sympathetic to Zygier, whose story is described as “the tragic downfall of a passionate Zionist, a young man who aspired to a life of heroism, and yet, in the wake of his own shortcomings, willingly gave away such sensitive information to the enemy that it represents one of the most serious security breaches in Israel’s 65-year history.” It is quite bizarre that an Israeli spy, who betrayed his Australian nationality by using his Australian passport to conduct intelligence operations for another country, is described in an Australian newspaper as someone whose downfall was “tragic.” Zygier was a shameless traitor to the land of his birth, and one can only conclude that his ultimate downfall, rather than being “tragic,” was entirely appropriate.

Ben Zygier was born in 1976 in Melbourne to a wealthy Jewish family. His father owned a food manufacturing business and became a leading figure in Melbourne’s Jewish community, serving as Chief Executive of the Jewish Community Council of Victoria. Educated at Jewish Schools, Zygier quickly became a passionate Zionist and joined the Zionist youth movement Hashomer Hatzair. After beginning a law degree at Monash University, he deferred his studies to move to Israel. He ended up living at the Kibbutz Gazit close to Israel’s border with Lebanon. There he met up with fellow Australian Jew Daniel Leiton and the two became friends. Koutsoukis notes that “Leiton recalls first meeting Zygier in the late ‘80s in Melbourne. Even then, he says, the two teenagers shared a passionate belief in Zionism, with Zygier already making it clear he would make Aliyah, the act of immigration for diaspora Jews to the land of Israel.” Another friend of Zygier, Lior Brand, described him as “obviously clever, and ready to defend Israel against its enemies, no matter what the cost.”

Zygier subsequently took Israeli citizenship under the adopted Hebrew name of Ben Alon. He then “flitted back and forth between Israel and Australia, in turn completing his law degree at Monash, and completing his military service in Israel.” In the early 2000s, the Israeli Institute for Intelligence and Special Operations (known as the “Mossad,” the Hebrew word for “Institute”) began its first ever public recruitment drive. Advertisements appeared in the Israeli press promoting “the job of a lifetime” and claiming “The Mossad is open – not for everyone, but for a few. Maybe for you.”

Zygier responded to the advertisement, and his application was warmly received. This is because, as Koutsoukis points out, “For an agency like the Mossad, which depends on its ability to send its agents unsuspected behind enemy lines, foreign-born nationals like Zygier offer an inherently valuable bonus – access to a genuine foreign passport that bears no link to Israel.” While Zygier pursued his legal career, first at a Jewish-owned law firm in Melbourne, and then in Tel Aviv, the Mossad was evaluating his potential suitability as an intelligence agent. They interviewed him as part of a psychological assessment to determine if he had any “obvious flaws or personality traits that might disqualify them from a career in the clandestine intelligence service.”

![]() Zygier was formally accepted into the Mossad in December 2003, and underwent an intensive year-long training program that “included such techniques as how to falsify resumes and other documents, and how to manipulate people.” In early 2005, Zygier was sent on his first mission to Europe with instructions to infiltrate companies that did business with Iran and Syria. Zygier initially targeted a technology company in Milan, and then other companies in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. For over a year and a half, he worked in various roles for a mid-sized European company with extensive business interests across the Middle East and Persian Gulf – including Iran. While regarded as intelligent and capable, Zygier’s erratic behavior, which at one point caused a major client to sever links with the company, eventually led to his dismissal.

Zygier was formally accepted into the Mossad in December 2003, and underwent an intensive year-long training program that “included such techniques as how to falsify resumes and other documents, and how to manipulate people.” In early 2005, Zygier was sent on his first mission to Europe with instructions to infiltrate companies that did business with Iran and Syria. Zygier initially targeted a technology company in Milan, and then other companies in Eastern Europe and the Balkans. For over a year and a half, he worked in various roles for a mid-sized European company with extensive business interests across the Middle East and Persian Gulf – including Iran. While regarded as intelligent and capable, Zygier’s erratic behavior, which at one point caused a major client to sever links with the company, eventually led to his dismissal.

Zygier gained no information of any strategic value to Israel while working for this company and, dissatisfied with his performance, he was recalled from the field in mid-2007 and assigned a desk job back at the Mossad headquarters in Tel Aviv. Koutsoukis notes that:

Inside the Mossad’s hexagonal headquarters off Tel Aviv’s Highway No. 5, the agency is divided into three main sections. Keshet, which means rainbow in Hebrew, is the first section, and is responsible for surveillance and other forms of covert intelligence gathering. The Caesarea department, which is named after the nearby ancient Roman settlement, is home to the Mossad strike force, the men and women who prepare and execute attacks abroad. The largest section is called Tzomet, which is Hebrew for crossroads, a more bureaucratic, less glamorous section that deals mainly with the evaluation and analysis of the information coming in.

Zygier was assigned to work in the Tzomet section. While there, because of recent changes in the structure of this department, he had unprecedented access to incoming intelligence from field operatives. It later transpired that the Mossad made a massive error in providing Zigier with this access to vital intelligence. In the spring of 2009, the Lebanese security services busted open several Israeli spy rings. Mustafa Ali Awadeh, an important Israeli agent in Lebanon, was arrested. Then, in May 2009, the Lebanese special-forces raided the house of the 61-year-old Ziad al-Homsi and arrested him on suspicion of spying for Israel. Homsi’s arrest in particular shocked the Lebanese public because he had previously served honorably as a mayor, and was regarded as a war hero for his exploits in fighting for the PLO against Israel, and for the Syrian army in the Lebanese civil war.

It later emerged that Homsi had been acting as an Israeli spy since 2006, and had received around $US100,000 for his information. The importance of Homsi to the Mossad is underscored by the fact that, under interrogation, he revealed that “he had told his Israeli handlers he could lead them to Hassan Nasrallah, the leader of Israel’s mortal enemy, Hezbollah, who has lived in hiding for years, thereby paving the way for another assassination.” The indictment against Homsi revealed to what elaborate lengths the Mossad will go to recruit a high-value target like Homsi.

According to Homsi, a Chinese man named “David” had come to his village in Lebanon, introducing himself to Homsi as an employee of the City of Beijing’s foreign trade office, and claiming that he wanted to establish business ties in Lebanon. At a business meeting in Lebanon, “David” invited Homsi to Beijing to attend a trade fair, telling him that the invitation had come directly from the Chinese government. Homsi enjoyed a successful visit to Beijing, where he was promised a salary. Later, he was invited to another meeting abroad, this time in Bangkok. But instead of talking business, the people on the other side of the table started asking Homsi what he knew about three Israeli soldiers who had been missing since a 1982 battle that Homsi had fought in on the side of the Arabs. “This is the moment at which the defendant becomes aware that he is dealing with Israelis, who work for the Mossad and have nothing to do with import-export companies or services that search for missing people,” reads the Homsi indictment.

Homsi agreed to work for the Mossad, which provided him with a computer and a doctored USB flash drive, as well as a device that looked like a stereo system but was in fact a transmitter for sending messages, all of which were seized upon his arrest. Homsi, says General Ashraf Rifi, the head of the Lebanese intelligence, was one of the most important catches his agency had ever made. Homsi was later sentenced to 15 years in prison with hard labor.

The arrests of Awadeh and Homsi represented the greatest setback the Mossad had experienced in decades. Attention soon turned to how the Lebanese had managed to uncover these agents. At this time the Israelis received a tipoff that talk within Hezbollah suggested a Mossad agent, then in Australia, could be in danger. It soon became clear that this agent was Ben Zygier, who, with the approval of the Mossad, had returned to Australia in early 2009 to pursue further study at Monash University. Concerned for his safety following the revelation that Hezbollah now knew his identity, Zygier was summoned back to Tel Aviv by his Mossad superiors in January 2009. When he arrived back in Israel, his superiors “thought that there was something odd about his behavior” and “the suspicion arose that he might have had a role in the arrests in Lebanon.” These suspicions only grew until January 2010, when Israel’s General Security Service, the Shin Bet, finally arrested Zygier. Under intense questioning, he revealed his connection to the arrests in Lebanon in 2009. It emerged that, in an effort to regain a coveted Mossad operations role, Zygier had embarked on a rogue mission without informing his superiors. Koutsoukis relates that:

Zygier, apparently frustrated by his demotion to a desk job, had decided to take matters into his own hands and find a way to rehabilitate his reputation in the organization. … [He] admitted that sometime in 2008, before he took leave of absence and moved to Australia, he had flown to eastern Europe to meet a man he knew to have close links with Hezbollah, with the intention of turning that person into a double agent. Instead that man reported the recruitment attempt to Beirut, and himself began playing the same game as Zygier, except in reverse. Without Zygier’s knowledge, the man was reporting every detail of his contact with Zygier back to the Hezbollah leadership in Beirut. Israeli officials believe even Hassan Nasrallah was being kept informed.

The contact between Zygier and the man went on for months. When the man asked Zygier for proof he was a Mossad agent, Zygier readily complied and began supplying him with real intelligence from Tel Aviv, including the names of Ziad al-Homsi and Mustafa Ali Awadeh, the Mossad’s two top informants in Lebanon. Israeli officials with access to the probe say that when Zygier was arrested, he was also found carrying a compact disc with additional classified information from the Tzomet department, which they also believe he was intending to hand over to the other side.

In his bungled attempts to redeem himself for his earlier failure in Europe, Zygier unwittingly became a conduit for information flowing from Tel Aviv to Hezbollah. Koutsoukis quotes an Israeli official who observed that Zygier “crossed paths with someone who was much more professional than he was.” While Israeli agents had changed sides in the past, a regular Mossad employee had never done what Zygier did in effectively becoming a double agent. Koutsoukis notes that the Zygier case represents “a bitter defeat for the Mossad, but for Hezbollah it is one of the rare instances in which an Arab intelligence service prevailed over its Jewish counterpart.” Sentenced to an indefinite term of imprisonment, Zygier (known to the Israelis as “Prisoner X”) was found hanging in his high-security prison cell on December 15, 2010.

The Ben Zygier case, while fascinating in itself, reveals how Israel, a supposed friend of Australia, has no qualms about using Australian passports to carry out intelligence operations on foreign soil. Zygier was employed by the Mossad and sent to Europe to infiltrate companies doing business with Iran and Syria precisely because his Australian citizenship enabled him to use his Australian passport for the operation. In encouraging their agents to use Australian nationality as cover for their work, the Mossad is engaging in the kind of behavior that could easily endanger Australian citizens. In releasing his department’s internal inquiry into its consular handling of the Zygier case, Australia’s Foreign Minister Bob Carr noted:

If Australian passports were misused here, that’s something we are forced to take very seriously, because no country can live with any erosion of the integrity of its passport system. If the world thinks that Australian passports are routinely debauched by another country, then Australians presenting their passport somewhere in the world could well face their lives in danger. We can’t live with that. And if that’s confirmed, we’ll be registering the strongest protest.

Unsurprisingly, the Israeli government’s response has been muted. The Australian government has sought more detail about the Zygier case from Israel, but Foreign Minister Carr has revealed that this information has “not been forthcoming.” The Zygier case is not the first instance of Australian passports being used by the Mossad as part of their operations. Evidence of the practice first emerged in 2010, when it was revealed that Israel had used faked Australia passports in their assassination of Hamas commander Mahmoud al-Mabhouh in Dubai that year. This had prompted the Australian government to expel an Israeli intelligence officer from the Israeli embassy in Canberra.

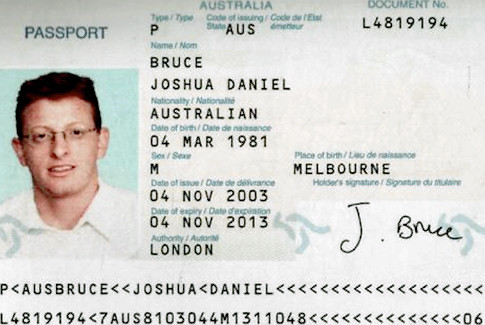

A fake Australian passport used in the Israeli assassination of Hamas leader Mahmoud Al-Mabhouh in 2010

Alone among Jewish commentators, Ben Saul, the professor of international law at the University of Sydney, admitted that the Ben Zygier case “illustrates the dangers of divided loyalties” and the dangers of allowing dual nationality (as Australia has since 2002). Writing in the Fairfax newspapers, he noted that: “From afar, Israelis may not have appreciated the fury of the Australian government and people after Mossad used fake Australian passports in the operation to kill a Hamas man in Dubai.” Saul labeled the practice “an illegal, hostile, and shameful act by Israel against a supposed friend, Australia.” Noting the potentially deadly consequences of this practice, Saul observes that “if other countries suspect that Australian passport-holders might be Mossad spies or assassins, it could cause a great deal of trouble for innocent Australians.”

Saul then got right to the crux of the problem of the Australian government allowing dual Australian-Israeli citizenship, observing that:

The case raises the broader problem of divided loyalties among Australians with multiple national identities, in this case some in the Jewish community. Australia permits dual citizenship. It becomes a problem where people put themselves in the position of having to choose between competing obligations of different countries, whether by spying or through military service. Israel and Australia are indeed good friends, but they are not always on the same page. For a start, there is a gulf in values. Australian security services do not assassinate people, including civilian scientists who are driving to work in neighboring countries. Australia does not torture prisoners. Australia has not militarily occupied a foreign people’s land for 40 years, or built illegal colonies on their lands. Australia does not believe in nuclear weapons or hide their existence. When it comes to the crunch, most Australians would expect Australian Jews to choose loyalty to Australia over Israel, or even hope that Australian agents in Mossad are our double agents. Undoubtedly, Israel would expect them to side with Israel. … There comes a point where a Jewish person cannot faithfully be both Australian and Israeli. One has to choose.

Not surprising, Saul’s plain-speaking sent members of the Australian Jewish community into apoplexy. The academics and Australian Jewish activists, Kim Rubinstein and Danny Ben Moshe, slammed Saul for “wanting to turn back the clock of globalization and multiculturalism,” and for using the Zygier case to “tarnish the Australian Jewish community by invoking classical anti-Semitic allegations of divided loyalty and the enemy within.” According to Rubinstein and Ben Moshe: “The failure of Saul’s argument, and the great offence it causes many Jews, is that for the overwhelming majority of Australian Jews, irrespective of whether they agree or disagree with specific policies of the Israeli government, identification with Israel as their cultural and spiritual homeland [note the careful avoidance of the term “ethnic homeland”] is part of being a Jew. It has been for millennia.” Rubinstein and Ben Moshe are certainly correct on that score – and therein resides the age-old problem of the Jewish presence within non-Jewish nations. Jewish identification and loyalty supersede all others.

Rubinstein and Ben Moshe were particularly aggrieved that Saul had invoked “the rationale espoused from darker periods of history calling on this boundary [of single nationality] to be imposed because fundamentally the loyalty of Jews cannot be trusted.” They angrily insisted that “Saul’s claim that ‘there comes a point where a Jewish person cannot faithfully be both Australian and Israeli. One has to choose’ is fundamentally wrong,” and that while Pauline Hanson tried to revive such sentiments towards Asians and other migrants in the 1990s, this is an archaic notion and today’s migrants in Australia and migrants all around the world have multiple identities that coexist and are balanced.”

Apparently it is not such an archaic notion in Israel, which retains a racially-restrictive immigration program which denies an Israeli identity to all potential migrants without Jewish ancestry. While Israel’s status as a Jewish ethno-state is accepted by Rubinstein and Ben Moshe as entirely uncontroversial (actually as a moral imperative at the core of Jewish identity), they condemn any concern over the divided loyalty of Australian-Israeli dual nationals as a despicable “turning back the clock of globalization and multiculturalism.” Of course, implicit in this specious argument is that “multiculturalism” is an apolitical default setting for social policy in Australia, rather than what it actually is: a radical political ideology which is a direct outgrowth of Jewish ethnic activism. Given their track record in reengineering Australian society in their own group interests, allowing dual nationality for Australian Jews was always likely to lead to the kind of behavior exposed in the Zygier case.

Comments are closed.