The Testament of a European Patriot: A Review of Dominique Venner’s “Breviary of the Unvanquished” (Part 1)

Dominique Venner, Un samouraï d’Occident: Le Bréviaire des insoumis (A Samurai of the West: Breviary of the Unvanquished; Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, 2013).

All Europeans, whether they are of the Old World or the New, are suffering today. Their very existence is demonized by a reigning culture which would prefer to see them blended into oblivion. Whereas the old beliefs — Christianity, communism, fascism — are dead or dying, no new faith has replaced them. We, ourselves, are dying as peoples, slowly vanishing from the face of the Earth. But some Europeans refuse to go down quietly, notwithstanding the base allures of comfort. So it was with Dominique Venner, an erudite historian and European patriot, who lived, fought, and died by the pen and the sword.

Venner’s last book — which translates as A Samurai of the West: The Breviary of the Unvanquished — presents itself as his political testament and his final attempt to reconnect Europeans with their tradition and thus awaken them ethnically and politically. This Breviary is not a traditional prayer book but rather presents “the substantive core” of the European tradition and is “a collection of writings, thoughts, and examples to which one can turn to every day to nourish one’s thoughts, one’s acts, and one’s life” (34). Venner says that the world-view implicit in this work can form the basis “to build the personal life of each of us, of families, of nations, and of living communities” (36).

The Breviary is then not only a wonderful introduction to Homeric and Stoic wisdom, but also has practical advice on day-to-day life: On establishing one’s own “breviary” of quotes from sacred texts and great thinkers, on communing with nature in the woods, on traveling across Europe like the Wandervögel, on cultivating beauty in one’s own life, or on the reconstruction of one’s family tree.

Venner’s legitimacy stems from a lifetime of struggle for the European peoples. Born in 1935, he volunteered as a young man to fight in the Algerian War to defend the 1 million European settlers in that country, who were threatened by ethnic cleansing at the hands of the Arab nationalists. Venner was enraged by President Charles de Gaulle’s decision to abandon Algeria despite military victory. He was imprisoned several times for his political activism, including an 18-month stint in 1961–62 for planning an armed assault on the Élysée Palace, presumably with the intention of killing De Gaulle. Behind bars with 30 other civilian and military rebels, often very senior, Venner says he “no doubt learned more from this on the drivers of history and its actors, great and small, than at university” (53). He later had a more nuanced appreciation of De Gaulle’s legacy.

Venner famously chose to end his life in 2013, by committing suicide in the Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris, that his final act too might contribute to awakening the European peoples.

The European Tradition

A real problem for those in search of a European identity in our twenty-first century, is that Europeans have been so culturally and ideologically fragmented across countries and throughout the ages. European have been Ice Age hunter-gatherers, conquering Aryans, pagan Greco-Romans, self-abnegating Christians, fratricidal nationalists, and, finally, universalist liberal egalitarians. We have nothing like the religious and ethno-national continuity of Japanese or Jewish history.

Venner however has no doubt of the fundamental unity and continuity of European civilization from the ancient world through the Middle Ages to today. For Venner, Europeans’ true self is “the spirit of the Iliad,” the great Homeric poem. This is a virile spirit which he argues has remained with us and periodically resurfaces throughout our history, such as in the chivalry of the medieval Romances or the neo-pagan art of the Renaissance. Venner notes that the Catholic Church, which more than anything gave spiritual and cultural unity to Western Europe in the Middle Ages, was inspired by neoplatonic philosophy and was a kind of heir to the Roman Empire. He points out that many of the Christian churches built in the late Roman Empire and early Middle Ages were in fact former Pagan temples, and that many of these temples in turn had been built upon sacred woods. Venner observes:

In 1711, four pillars [. . .] were discovered under the choir of Notre-Dame Cathedral in Paris, going back to the first century of our era. They represent the Celtic deities once venerated in a Gallo-Roman temple on which twelve centuries later the Christian cathedral was built. (68)

This, no doubt, explains why Venner chose Notre-Dame Cathedral as the place for his spectacular suicide: The cathedral, though Christian, was the most central and most awesome sacred place showing spiritual continuity with the earliest European peoples in France. (Venner in general, while approving of Christian architecture and beauty, has a basically Nietzschean critique of Christian ethics as debilitating and guilt-inducing.) As a “mediative historian” (his expression), Venner sought throughout his adult life to make Europeans aware of their ancestral tradition, and hence, turn them into a conscious people with political agency.

Race and Civilization

But who are the Europeans? Why has there been continuity in their civilization? Venner defines Europeans as “the sons of the different peoples of the great Borean fatherland” (289), that is to say the sons of the north. Boreans in turn are “Europeans of ancient stock” (187). The continuity in our variegated civilization was the reflection of the European soul. Venner argues that the characteristics of civilizations “are the reflections of a certain spiritual morphology, transmitted no doubt as much by atavism as by learning” (123). Put another way, that most complex and high-level phenomenon which is European civilization, reflects the underlying European personality, which insofar as it is genetically determined, necessarily has significant continuity since the days of Homer.

If the underlying basis of European civilization and peoplehood is biological, then demography indeed is destiny: “the stakes of history are always found in the space and the soul of peoples, in the atavistic sense of the word” (56). Hence, the ultimate threat to a people is its physical replacement and elimination: “the roots of civilizations are practically indestructible as long as the people which was its mold has not disappeared” (125). Thus Venner has the harshest words against mass migration towards European lands:

[An] odious and perverse project to denature Europe by a replacement of the population. In their struggles, the immigrants however find public assistance to their benefit, charitable actions, the support of a clannish solidarity and the moral support that can bring them the return to Islam, a religion of their part of the world.

The fate of French that we call “de souche” [i.e. ethnic], those who, in the banlieues, are called “Gaulish,” seems to me all the more poignant and desperate. And I know it is the same everywhere in the disfigured Europe of today. I therefore reserve my compassion for these Europeans “de souche.” (9-10)

And if this monstrous undertaking, whose consequences will be paid for at an exorbitant price in the long run, has been able to impose itself, it is of course because of the complicity of perverse or decadent elites, but also especially because the Europeans, unlike other peoples, are lacking in identitarian memory and in consciousness of who they are. (21)

Venner clearly identifies culture as a primary factor in European unconsciousness and decline. He argues that Europeans were psychologically prepared for displacement by a long tradition of both religious and secular universalism. Politically, Europe was effectively neutralized by World War II, coming under American and Soviet domination in 1945. Emotional manipulation also plays a role: “[W]e are in addition plunging into an unparalleled guilt. According to Élie Barnavi’s eloquent phrase: ‘The Shoah has raised itself to the rank of a civil religion in the West’” (22). Barnavi, an Israeli historian and diplomat, apparently has the same view as the Franco-Jewish pundit Éric Zemmour on this matter.

Homer: Our Sacred Poems

Europeans are faced with the challenge of finding a “useable past” — a tradition and frame of reference which all people of European descent can turn to. For Venner, the foundation of Western civilization is neither the New Testament nor Enlightenment philosophy, but above all the great poems of Homer. These poems are odes to heroism and virility, to the warrior ethos, to the love of beauty, to the sense of tragedy, to exalted patriotism, and to harmony with Nature.

On all this I can do no better than quote Venner at length:

According to Plato, Homer was the educator of ancient Greece, therefore [he is] ours by spiritual inheritance and a distant consanguinity. To Europeans who are asking themselves questions about themselves and their identity, the two great poems offer a mirror by which to find again their true inner face, freed of what had disfigured them and often made them err, anxious and lost. (168)

Inspired by the gods and poetry, which are but one, Homer has given to the Greeks and the Europeans the founding books to which to always turn to find themselves again. (169)

These sacred poems tell us in an unsurpassed way who we were at our dawn. (176)

[T]hey tell us that our fears, our hopes, our sufferings, and our joys have already been lived by our forebears. (177)

“Sing, O goddess, the anger of Achilles’ [the opening line of the Iliad].” This goddess who sings the epic is the Muse of memory, of whom the poet is the interpreter, which underlines his ties with the divine world. (191)

For Homer, life, this little ephemeral and so commonplace thing, has no value in itself. It has value only by its intensity, its beauty, the breath of greatness that each — and firstly in one’s own eyes — can give it” (197).

Far from being models of perfection, Homer’s heroes are the subjects of error and excess in the very proportion of their vitality. [. . .] But on the part of Homer, what generosity and higher wisdom too, which frees humans from the imaginary guilt which other beliefs would burden them with. (201–202)

How far all this is from the short-sighted, self-indulgent individualism of the 1960s cultural revolution!

Venner strongly emphasizes the notions of patriotism and community in Homer:

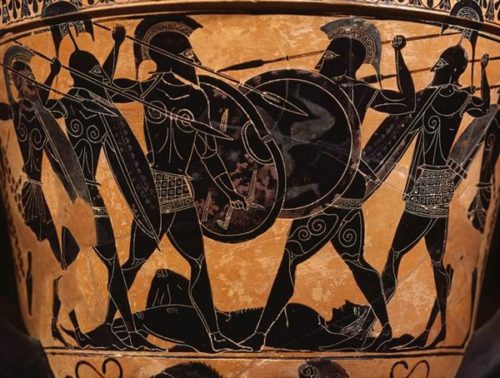

In a famous passage of the Iliad (book XIII), the poet describes the Achaean phalanx: “[They made a living fence], spear to spear, shield to shield, buckler to buckler, helmet to helmet, and man to man.” It is not only a foreshadowing of the hoplite order that we see here, but especially the expression of what is a solidary community where every member can rely on the others, where desertion of a single member would instantaneously annihilate the indivisible whole. There is no question of a “contract” here, but mutual obligations inscribed in the founding pact of the clan, of the tribe, of the polis, and of the phalanx. (190)

There is nothing more heart-felt or more relevant today than [the Trojan hero] Hector’s love for his fatherland, of which his wife and son are the concrete images. (205)

Venner comments on Odysseus’ return to Ithaca, taking revenge against the “pretenders” and returning to harmony with nature through a sacrifice to Poseidon: “The foundations of the social order and of civil peace are the ethnic unity of the polis and the respect for the laws, guaranteed by the Ancients and by force” (218).

There is also the tragic sense in which our very difficulties give greatness to our endeavors, noting that in the stories of Achilles, Tristan, or Hamlet:

By the grace of the work of art, the worst (“[Achilles’] black rage”) can transform into a good, that is to say beauty. [. . .] The crueler is the fate, the greater it is, the more beautiful it is. Here, Homer accomplishes in a striking way the esthetic reversal made by the tragic spirit. It awakens in us the thirst for heroism and for beauty. We need to remember this when we are ourselves confronted with misfortunes born of war or the happenstances of life. (230)

Or as Homer puts it: “Zeus gives us an evil fate, so we may be subjects for men’s songs in human generations yet to come” (Iliad, book VI). Venner sums up Homeric ethics: “[T]he struggle towards beauty is the condition for the good” (232).

This recalls Ricardo Duchesne’s emphasis in The Uniqueness of Western Civilization on the heroic Western tradition stemming from our Indo-European forebears. An essential aspect of of this heroic tradition is the ethic of striving for renown, of which Homer is an exemplar. Duchesne quotes these lines from Beowulf:

As we must all expect to leave our life on this earth, we must earn some renown,

If we can before death; daring is the thing

for a fighting man to be remembered by. …

A man must act so when he means in a fight to frame himself

a long lasting glory; it is not life he thinks of.

Pro Patria

Notwithstanding the very real strains of universalism in European thought throughout our history, Venner notes that patriotism and a sense of European identity, separate from Africans and Asians, have also been important. He notes:

[Homer] had also powerfully expressed how important it is for the individual to have vital feeling of belonging to a people or to a polis which preceded him and will outlive him. Through this belonging individuals cease to be separated. (243)

The fatherland is the idealized family household which is merged with the future of the polis. It is the sacred land where the ancestors rest. (246)

Venner notes this feeling of community and continuity is deeply reassuring and satisfying for individuals, who otherwise are liable to feel their existence is isolated, short-lived, and meaningless. Personally, I believe such a feeling of anomic depression has contributed at least in part to the unprecedented decline in life expectancy among European-Americans (and possibly Frenchmen as well), driven essentially by self-neglect: Unhealthy living, alcoholism, drug abuse, etc. As Venner notes:

Even when they don’t know it, individuals and peoples have a vital need for roots, for their own traditions and civilization, that is to say for reassuring continuities, rites, internalized order, and spirituality. (293)

Venner quotes the poet Aeschylus 300 years later in The Persians on rousing the Greeks to repel the hordes of Asia:

On, sons of Greece! Set free

Your fatherland, set free your children, wives,

Places of your ancestral gods and tombs of your ancestors!

Forward for all

He also recalls Roman poet Horace’s famous line: “Dulce et decorum est pro patria mori!” (“It is sweet and glorious to die for one’s fatherland.”)

Venner notes that, throughout history, Europeans have been conscious of their uniqueness even when, being among themselves, they did not state this explicitly:

When [the ancient Greeks and Romans] said “men,” they did not think of humanity in general. They were thinking of the Greeks or of the Romans, free citizens, virtuous, and endowed with reason. In this respect, the Europeans of the Enlightenment were like them, for whom “men” implicitly meant Europeans. (258)

Comments are closed.