“The Book and the Rifle”: Cultural and Racial Policy in Fascist Italy, Part 2

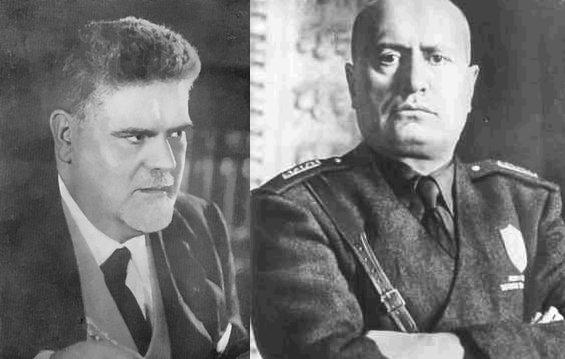

Giovanni Gentile and Benito Mussolini

Intellectual Debate in Fascist Italy

Tarquini emphasizes that culture in Fascist Italy was by no means monolithic, but allowed considerable stylistic variation and intellectual debate so long as these respected core Fascist principles. Indeed, Fascists emphasized that being a Fascist was more about a certain manly mindset than about theoretical abstractions. As Nietzsche did, the Fascists rejected the bourgeois spirit with its satisfaction with mediocrity, its skepticism and compromise, its concern with careers, and its death-fearing selfishness.

Fascism was born out of diverse groups dissatisfied with Italy’s small gains during World War I, frustrated with liberal impotence, and disturbed by the rise of communism. These included military veterans, self-sacrificial arditi soldiers, futurist artists, revolutionary syndicalists, socialistic republicans, and others. Fascism emerged organically as “a militia in the service of the nation,” a political movement, and finally a government, rather than as a preset set of ideas.

The “spirit of the trenches,” the spirit of hierarchy, discipline and community, which had shown its awesome destructive power in wartime would be used by the Fascists to constructively develop the nation in peacetime. Indeed, Fascism developed a “secular liturgy” (p. 43) and “a conception of the nation elevated to a sacred entity” (p. 51). Fascism rejected internationalism, egalitarianism, and materialism, embracing aristocracy, spirituality, and nationalism. Some Fascists even credited their movement with the potential to save Europe from decadence and degeneration.

Fascism was unabashedly communitarian. Economics and culture were to respect community interests. The Fascist doctrine of corporatism reflected “the relevance to the state [statalità] of every economic phenomenon” (p. 157). Fascists similarly argued that writers had “a political, moral, and educational role” and culture had to support “the struggle for civilization” (p. 184).

For example, one Fascist described appropriate literature as that which followed “the fundamental canons” of Fascism: discipline, hierarchy, “to intensely love the nation,” and “to repudiate the forms of literature exalting class struggle, internationalism, and every principle of disintegration of the race” (p. 94). Novelists were not expected to undertake their work in a spirit of esthetic vanity for its own sake. Within these bounds, which admittedly excluded Marxist, libertarian, and egalitarian works, considerable freedom existed. The Fascists extended such ideas to all cultural fields, arguing, for instance, that philosophy should serve community interests and that art should appeal to the people.

Tarquini documents substantial ideological debates in Fascist Italy, reflecting different ideas but also less interesting conflicts between cliques and personalities. While all Fascists agreed that culture was political, they debated the extent to which culture should benefit from autonomy or should be determined by policy. Delio Cantimori, influenced by the German jurist Carl Schmitt, argued that “it is a genuine liberal folly to want to establish a cultural sphere independent from politics” because “the decision whether something does or does not pertain to the political is always a political decision” (p. 101). And if culture was political, politics was to become artistic.

There were also debates on the relationship between nation and state, and on which had primacy over the other. The philosopher and educator Giovanni Gentile argued that Fascism was an extension of Italy’s nineteenth-century process of unification and nation-building. Tarquini writes that he “expressed with clarity the problem of the formation of a national consciousness which, in his view, was a moral question” (p. 125). More radical Fascists argued that the state had a decisive role in crafting and reshaping the nation, one Fascist declaring in a perhaps excessive flourish: “the Fascist state not only dominates the nation, but reabsorbs and eliminates it” (126). Still others argued more modestly that “the nation precedes the state” and that “the best patriotism is a natural fact, not a political one” (185).

These debates often seem to have had a rather pedantic ‘theological’ quality, but they reflect the passionate importance these ideas had for Fascists. Alfredo Rocco, a leading Fascist jurist, “defined the nation as the highest expression of contemporary sociality and argued that politics meant disciplining the social forces for the achievement of the society’s higher objectives” (p. 115).

Others however identified the moral leadership of the state or the grandeur of empire as more significant to the Fascist ideal. One defined the state as a movement and a process reflecting “the moral and social unity of the people expressed, lived, and personified in the State,” and dedicated to the elevation of souls (p. 118).

There was also debate on whether Fascism was a revolutionary or traditionalist force (in fact it was a mixture of both) and on the place of Catholicism and traditional elites. From 1921 onward, the Roman Empire became a central symbolic reference of the Fascists, evident in the fasces, the eagles, the Roman salute, and so forth. Cities were reshaped with substantial public works to emphasize Roman monuments as “sacred places of antiquity” (p. 131). At the same time, Tarquini emphasizes this was not motivated by a backward-looking sentiment: Fascist cities were aimed to be modern, future-oriented, reflecting a new civilization meant to last for centuries.

A unifying force in all this was the figure of Mussolini as the Duce, who was promoted by the Party and mass media as a “living myth.” Mussolini, by his charisma and his usage of modern propaganda techniques, developed an enormous, devoted, and even “superstitious” mass following. The masses, and most importantly the youth, came to identify powerfully with their glorified tribal chieftain.

Fascist Schooling

The fascist educational program can be considered a furthering and gradual radicalization of previous programs meant to consolidate and build the Italian nation-state. Italy had only been united in the 1860s and 1870s, retaining considerable regional linguistic and cultural variation.

In June 1919, Mussolini’s newspaper, Il Popolo d’Italia, asked that schools be “formative of national consciousness,” “discipline souls and bodies for the defense of the Fatherland,” and “elevate the moral and cultural conditions of the proletariat” with “a patriotic education” (p. 58). This would include mandatory physical education and pre-military training. The original Fascism was fairly “progressive” and left-wing, reflecting Mussolini’s Socialist roots, being anti-clerical, republican (opposed to the monarchy), and calling for support for poor students.

The Fascist Party’s October 1921 program called for selecting teachers who were “capable of guaranteeing the economic and historical progress of the Nation, to elevate the moral and cultural level of the mass and to develop … the best elements to ensure the continuous renewal of the ruling classes” (p. 60).

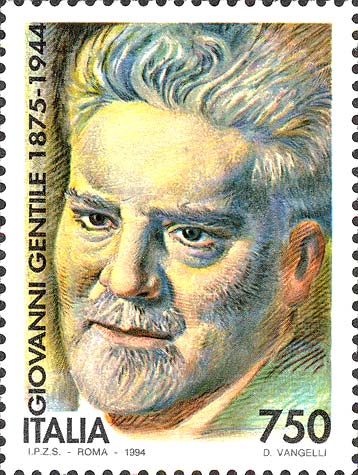

Giovanni Gentile

Minister for Public Education Giovanni Gentile’s 1923 school reform, once called “the most fascist” of reforms by Mussolini, continued to influence the Italian education system into the postwar period. Among other things, the reform instituted mandatory schooling until the age of 14, separate classes for less gifted students, and high school for girls. It also created the liceo classico (classics high school) which was the only high schools to allow “enrollment into all university departments; it was the school which was to educate the future ruling class, the most selective and prestigious, where history and philosophy, Italian, Latin, and Greek were taught” (p. 66).

Teachers were required to swear loyalty to the state but universities initially still retained considerable autonomy. Private religious schools were maintained to absorb the excess population which the state could not provide for, an important service given that 30% of Italians were still illiterate (p. 57). The schools, more explicitly than before, taught a patriotic civil religion, classrooms being required to have photos of the king of Italy, crucifixes, salute the Italian tricolor flag, sing patriotic songs, and commemorate the dead of the Great War. This was to be done, the government stressed, with a “religious solemnity.”

Tarquini summarizes Gentile’s educational ideal thus:

Gentile contributed to creating a regime which celebrated the myth of the State and had an absolute conception of politics: a State in which public bodies, institutions, organs, groups, and individuals had to collaborate to realize a new order in a common and shared work; and a politics understood as a faith which would transform consciousnesses and found a new national reality giving the Italians the sense of their identity. (p. 152)

Over time, Gentile’s reform came to be seen as too moderate and one can see a steady ideological radicalization as the regime consolidated and as the young generation, educated in Fascism, rose to power. Gentile had said that “education is self-education, autonomous and free development of our spirituality” (p. 222). More radical Fascists posited that culture should not develop autonomously from the state.

In 1927, schools began teaching the history and ideology of Fascism and providing students with days of sports and touristic excursions, both considered necessary for the education well-rounded young Fascists. In 1928, most school books were required to align with Fascist ideology and even esthetics (beauty always being a major concern for fascists).[1] In 1929, education became a state monopoly. University professors were required to swear loyalty to the King and the Fascist Regime, with only 1% refusing (p. 147).

In February 1939, Minister for National Education Giuseppe Bottai presented a new School Charter which stated:

In the moral, political, and economic unity of the Italian Nation, which realizes itself integrally in the Fascist State, the School, first foundation of solidarity between all of the social forces, from the family to the Corporation, to the Party, shapes the human and political consciousness of the new generations. (220)

Practically, Italian students were given professional training aimed at inserting them into the labor market and they were required to undertake some manual labor as part of their education in order to instill respect for workers. Academic works self-consciously aimed to shape young people. For instance, the 1940 Dizionario di politica (Dictionary of Politics) declared that it aimed to “free [the young generations] from the superstructures with which demo-liberalism deludes itself in [seeking] to fix the life of nations” (p. 226).

The Fascists were proud of their revolution and their giving the common people previously unavailable opportunities for upward mobility. An enthusiast defined the fascist revolution as “the first and most characteristic popular revolution of modern times, enabling the masses to enter into the schools of the bourgeois” (p. 222).

Organization of the Youth

In addition to the schools, which were controlled by the state rather than directly by the Party, the Fascists created youth groups. These were initially volunteer activist organizations which gradually became mandatory, including the Avanguardia studentesca (Fascist Party Youth Organization), later absorbed by the Opera nazionale balilla (ONB), the national male youth organization. Party officials considered the ONB “one of the most important institutions of the regime” (p. 80). This partly reflected institutional rivalry with the state, as the ONB was directly controlled by the Party, but also indicated the importance Fascists gave to molding the youth in order to instill unity and martial values. Only Catholic youth groups were tolerated as an alternative, and these were not allowed to engage in sports.

The goals were to educate and toughen the new generation. One Fascist wrote that the new man would accept “with joy the hardest of disciplines” and that Fascist sport must “be understood as a militia, that is as discipline and as virile education of the citizen” (p. 79). By 1930, Tarquini writes that Italy had become “a giant barracks,” or we might say a modern Sparta. The Fascists, however, unlike the Spartans, recognized the importance of culture.

The very choice of the name balilla, meaning a young boy, was significant. Balilla was the nickname of Giovan Battista Perasso, a Genovese boy who during the eighteenth century was said to have sparked a successful revolt against the occupying Austrians by throwing a stone at a Habsburg official. (An ideal balilla is featured on the cover of Tarquini’s book: a boy in a fine black uniform throwing a stone.) The ONB’s slogan: “Libro e moschetto, fascista perfetto” (Book and musket, [make] a perfect fascist).

New media technologies, notably radio, were also used. Tarquini writes of one such radio program, Il Giornale radiofonico del fanciullo (Children’s Radio News), as:

a very popular program made up of short news items on the events of the day, interspersed with music, completed with the reading of a story or the chapter of a novel. Hosted by the Roman master Cesare Ferri, with the pseudonym of Nonno Radio (“Radio Grandpa”), giving particular attention to the history of Italy, from the Risorgimento [unification of Italy in the 1860s and 1870s] to the Great War. (174)

Fascists occasionally asserted that the Party’s main role was educating the people and bringing the best elements to the leadership of the state. This included for instance the creation of the Centro nazionale di preparazione politica (National Center for Political Preparation) which brought in young men over 28 who had completed military service, had a regional political preparation diploma, and were or had been in the youth group. They were to be trained to be the new elite. Courses included Fascist doctrine, the history of the Fascist Revolution, organization of the Party and state, racial policy, and military culture.

University students raised in the Fascist system were often enthusiastic supporters, being fascinated by Mussolini and the revolution, and responsive to the regime’s exhortation to take responsibility as the future ruling class. Tarquini notes that in the postwar era “various youthful fascists, having become antifascists, reconstructed their own experience in the regime,” to falsely claim they had been already disenchanted in the 1930s by seeing its “reactionary” nature (p. 157).

The Fascists saw the unification, education, and training of the youth as one of their most important duties, to be achieved by schooling and participating in youth groups. Bottai described the goal as instilling “the discipline of culture and that of physical and warrior education, the meditative cult of tradition and that of action which leaps forward [brucia le tappe, or “skips steps”] and looks to the future” (p. 221).

Workers and Women: Integration, Education, & Organization

The Fascists took similar care in organizing the rest of society in general, notably the working masses and women. This was notably undertaken by the Opera nazionale dopolavoro (OND), which was charged with organizing “after-work” activities. In fact, as in National Socialist Germany, this was a truly ground-breaking, innovative, and massive social undertaking, including both tourism and education. The OND organized physical, moral, and artistic education, as well as sports, touristic excursions, exposure to popular culture, as well as training in hygiene, health, and professional skills. The Italian Fascists thus pioneered mass tourism, with the launch of treni popolari (popular trains) allowing ordinary people to travel.

A major cultural program was undertaken by the traveling theater and music shows known as Carri di Tespi (Thespian Wagons, named after the first ancient Greek actor), which “brought the great classics to the remotest corners of Italy” (p. 172). These were a massive undertaking, reaching millions of spectators.

The stated goal was the education, organization, and social integration of the masses, something previous regimes had neglected. By 1941, 24.5 million Italians, well over half the population, were affiliated with the Fascist Party in some way, about 20% being full members and the other 80% being in the various Party organizations, including 8.1 million in the youth group (p. 158). This became a huge part of the day-to-day life of Italians. Indeed, this tradition continued after the war, with sports and cultural life revolving around party affiliation.

Tarquini notes that under Fascism “women were the object of paramount attention as had never happened under previous political regimes” (p. 161). Fascists considered that women, like all individuals, needed to be educated and act in service of the community. This meant maintaining some traditional roles, namely that of mother and caregiver, and changing others.

A good example of this was the Opera nazionale maternità e infanzia, launched in 1925 to provide support and welfare for mothers. This organization boasted that it had prevented many children from becoming orphans by convincing young mothers to keep their children even if these were the fruit of an illicit liaison and, if possible, to regularize their extramarital union. This was a decidedly practical and pro-social approach to traditional gender roles.

Women were encouraged to participate in political life, but not to the detriment of their duties as mothers and caregivers. By 1942, over 1 million were members of the feminine fasces Party organizations (p. 163). The Fascists in general promoted the family and fertility as factors of social cohesion and population growth, and therefore of national power. Pro-natalist policies were instituted, including a 1926 tax on celibacy; promoting abortion became illegal.

More generally, the government took a holistic and systematic approach to popular culture. Censorship in Italy was neither invented by the Fascists nor ended with their fall. Nonetheless, censorship as an official and unabashed part of government policy under Fascism. Journalists were expected to act as “educators of the people.” Mussolini on one occasion said journalists should consider themselves “soldiers” (p. 164) in the movement.[2] Such censorship could of course hide malfeasance or corruption, but it was officially justified as ensuring national cohesion and promoting a healthy culture.

The Ministry of Popular Culture (Minculpop) was charged with educating the masses. It secretly subsidized intellectuals, artists, and journalists (the latter getting 55% of such funds [p. 166]). Gentile was put in charge of a National Fascist Institute of Culture, attached to the Party, which created cultural centers organizing public lectures and gatherings, concerts, excursions, language instruction, and museum visits. The Institute also published numerous publications for libraries and schools (p. 71).

The government was also very interested in the power of cinema, employing well-regarded filmmakers such as Roberto Rossellini.

In general, the Italian media under Fascism promoted government narratives. For example, the conquest of Ethiopia was justified on grounds of civilizing a backward nation and Italian participation in the Spanish Civil War was part of a crusade against Bolshevism. When Italy later passed anti-Jewish legislation, crimes committed by Jews and the anti-Jewish legislation of other countries were systematically reported on (p. 165). Sports and media discussions of sports were exploited to discretely promote the regime’s ideology of martial vigor and “improvement of the race.”[3]

[1] One can compare this with the postwar development of political correctness, whereby any overt expression of fascist, reactionary, racial, nationalist, or even non-egalitarian ideas became largely and increasingly banned across Western academia, while Marxists prospered and libertarians were tolerated.

[2] Adolf Hitler had much the same view:

I had some difficulty, also, in persuading the Old Gentleman [President Paul von Hindenburg] of the necessity of curtailing the liberty of the press. On this occasion I played a little trick on him and addressed him not as a civilian with “Mr. President,” but as a soldier with “Field Marshal,” and developed the argument that in the Army criticism from below was never permitted — only the reverse, for what would happen if the N.C.O. passed judgment on the orders of the captain, the captain on those of the general, and so on? This the Old Gentleman admitted and without further ado approved of my policy, saying: “You are quite right, only superiors have the right to criticize!” And with these words the freedom of the press was doomed. (Table Talk, May 21, 1942)

[W]hat a task of immense educational value he [National Socialist newspaper publisher Max Amann] has thus accomplished ! He has molded exactly the type of journalist that we need in a National Socialist state. We want men who, when they develop a theme, do not first of all think of the success the article will bring them or of the material benefits it will give them; as formers of public opinion, we want men who are conscious of the fact that they have a mission and who bear themselves as good servants of the state.

As a supporter of this viewpoint, I have tried, since I came into power, to bring the whole of the German press into line. To do so, I have not hesitated, when necessary, to take radical measures. It was evident to my eyes that a State which had at its disposal an inspired press and journalists devoted to its cause possessed therein the greatest power that one could possibly imagine.

Wherever it may be, this fetish of the liberty of the press constitutes a mortal danger par excellence. Moreover, what is called the liberty of the press does not in the least mean that the press is free, but simply that certain potentates are at liberty to direct it as they wish, in support of their particular interests and, if need be, in opposition to the interests of the state.

It is not easy, at the beginning, to explain all this to the journalists and to make them understand that, as members of a corporate entity, they had certain obligations to the community as a whole. And endless repetitions were necessary before I could make them see that, if the press failed to grasp this idea, it would end only in harming itself. Take the case of a town with, say, a dozen newspapers; each one of them reports the various items in its own way, and in the end the reader can only come to the conclusion that he is dealing with a gang of opium-smokers. In this way the press gradually loses its influence on public opinion and all contact with the man in the street. The British press affords so excellent an example that it has become quite impossible to gauge British public opinion by reading the British newspapers. This has been carried to such a pass, that as often as not the press bears no relation whatsoever to the lines of thought of the people.

That is exactly what happened in Vienna before 1914, in the time of Mayor [Karl] Lueger. In spite of the fact that the entire Viennese press was in the hands of Jewry and in the pay of the Liberals, Lueger, the leader of the Christian Social Party, regularly obtained a handsome majority — a fact which showed all too clearly the hiatus existing between the press of Vienna and public opinion. (Table Talk, May 14, 1942)

[3] It appears that all governments and organizations have an incentive to exploit man’s natural attraction to sports, whether as participant or spectator. In our society, soccer, American football, basketball, and other sports are also exploited for ideological and economic goals. These sports have become enormously commercialized in the name of corporate profits, embodied in the crassness of rootless international football clubs and Superbowl ads. Politically, soccer, the most popular sport in the world, has no values other than opposition to “racism” (e.g. the Union of European Football Associations’ [UEFA] principle campaign: “No to Racism”). Impressionable men, particularly the young and the working class, who would otherwise often have an ethnocentric disposition, identify with these glamorous sports stars, who play in multiracial (and, increasingly, minority-majority) teams. Our young men then may be less inclined to identify themselves ethnically and may shame themselves for having ethnocentric instincts.

Comments are closed.