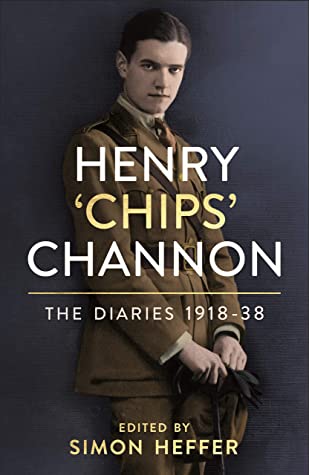

Chip’s Diaries

Henry ‘Chips’ Channon: The Diaries, 1918–38

Edited by Simon Heffer.

London: Hutchinson, 2021

In his 2008 book Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War[1] Pat Buchanan suggests that with a bit of prescience and a steadier hand at the tiller Britain could have avoided World War II. If the policies supported by American-born MP and diarist Henry ‘Chips’ Channon had been adopted, that devastating European war would have been averted and Soviet communism might have been destroyed half a century before its fall.

Channon was born in Chicago in 1897 to a wealthy American family. His grandfather had started a Great Lakes shipping company. The young Channon spent two years at the University of Chicago before going to France to help with the war effort as a volunteer with the American Red Cross. He fell in love with Europe and never spent much time in America thereafter.

After the war he enrolled at Christ Church, Oxford where he received a degree in French and the nickname ‘Chips.’ Being a gentleman of that era Channon had no need to work for a living. As editor Simon Heffer notes “until he became a Member of Parliament in 1935 Channon seems to have had no job that paid him a salary” (XI). Not only did he have a family fortune, in 1933 he married money—Honor Guinness, an heiress to the brewing company.

Although very wealthy, Channon was not idle. He published three books between 1929 and 1933, two novels and a history, and was one the leading diarists of the twentieth century. The book considered here, 950 pages with thousands of footnotes supplied by editor Simon Heffer, is the first of a three-volume set of Channon’s journals. It covers the years 1918–1938. The second volume will cover the war years, and the third the post-war period until Channon’s death in 1958. There are three main areas of interest within these diaries. In ascending order: Chips’ personal life, his political ideology and views on Jews, and his involvement in British foreign affairs, especially with regard to relations with Nationalist Socialist Germany.

One puzzling aspect of Channon’s character was his sexuality. Editor Heffer describes him as bisexual. This is troubling because the authentic Right considers sexual deviance to be a serious social problem. There is little in this edition to indicate that Chips was other than heterosexual. He had an eye for feminine beauty and expressed that he was physically attracted to women. “Honor’s appearance was really fantastic . . . like a tousled Garbo” (656). He was deeply in love with his wife, at least during the early years of their marriage. He adored his son and wanted more children, though Honor did not. It is alleged that later in life, after his marriage failed, that he had several homosexual relationships. That period is not covered in this volume.

His sexuality aside, Channon’s diaries convey a lifestyle of European high society that is as gone with the wind as that of the antebellum South. It was a nearly all White, Eurocentric world populated by princes and princesses, lords and ladies. Even in the French Third Republic and the German Weimar Republic aristocrats and former royalty still used titles as part of their legal name. Though these titles conveyed no official privileges, those who possessed them formed a distinct social class. Money from commerce, if it was several generations old, could—but would not necessarily—permit one to enter. One example is Chips’ wife, Lady Honor Guinness daughter of Rupert Guinness, 2nd Earl of Iveagh. Though divided by politics and personalities, this was a society united by a general agreement on cultural norms. It was also a society of endless formal luncheons, dinner parties, elite entertainment, and trips aboard. Incidentally, if one has the means, entertaining is a great way to win friends and influence people. These people were privileged. It is ludicrous for the Left to speak of today’s struggling middle-class White families as privileged.

Channon’s political and social views were probably typical of right-wing Tories between the wars. He did not harbor an animus towards Blacks or Jews He occasionally socialized with Jews and had some commercial relationships with them, but he had a strong ethnic/cultural identity that viewed them as other. The expression of this consciousness was enough to cause consternation for those involved with the publication of these diaries. “The Trustees, editor and publisher deliberated at length whether to include or exclude such passages from this edition. After careful consideration, and consultation with external authorities [who might they be?] it was decided to leave them in, while seeking through the footnotes, to contextualize them” (XIV).

Henry ‘Chips’ Channon

The dreaded N word does appear once. In 1927, during one of his infrequent trips to America, Channon witnessed firsthand the so-called Harlem Renaissance. He writes, “New York is black mad.” He attends the new Broadway play “Porgy,” later turned into the musical “Porgy and Bess.” Chips notes, “a wonderful cast, all negroes.” In a footnote editor Heffer writes that the play portrayed the “culture of black Americans with what for the time was unusual sympathy and respect” (289). The play was based on a book by the same name written by a White southerner Edwin DuBose Heyward. Channon also mentions a book, Nigger Heaven that was published about this time. Also written by a White man, Carl Van Vechten, it did much to publicize the new urban Black culture of the 1920s. Certainly none of this suggests a deep antipathy towards Blacks.

There are examples of Channon’s mild “anti-Semitism” sprinkled throughout his diaries. For instance, in January 1935 he remarks that Hannah Gubbay, ‘old black Hannah,’ had “hitched her wagon to cousin Philip Sassoon’s star—they are inseparable and always up to God knows what plots and plans and social schemes. A mysterious dark brace of Semites” (378). Three years later: “Poor Professor Loewenthal called here this afternoon to give us the crystal medallions of [his wife and son] Honor and Paul. He is dreary, gloomy, but the greatest artist since Benvenuto Cellini. He looks like one of the Pharaohs and carves in metals and precious stones. He is a refugee Jew” (900). As we will see below, Channon’s disapproval of Jews was principally political, but also cultural and aesthetic.

So what were Channon’s politics? Today he might be considered a paleoconservative, but reactionary may be a better description. He was a vehement anti-communist at a time when Soviet-styled communism posed a real threat to Europe. He admired German culture, but was definitely not a Nazi. National Socialism was a revolutionary ideology and Channon supported the monarchy and aristocracy. This is why Chips was a firm Tory, not swayed in the least by Oswald Mosley’s fascism. Channon knew Mosley personally. He was a guest at a Channon dinner party in January 1935. The host writes, “Tom [Oswald Mosley] was charming and gentle and affectionate as he always is, except on the platform where he becomes the demagogue” (379). Mosley’s ideology was too populist for Channon’s taste. Editor Heffer believes Channon simply “discounted as ineffectual” Mosley’s Blackshirts (543).

Channon was a strong believer in national sovereignty. Thus he had a poor opinion of the League of Nations, “a cursed body of busybodies” (486). He attended a League session in Geneva in September 1938. He saw the assembly as “an anti-German organization. The bars and lobbies of the League building are full of Russians and Jews who intrigue and dominate the press” (920). One of the Jews that Chips was referring to was Comrade Litvinov. “Meir Henoch Wallach-Finkelstein, who later took the nom de guerre Maxim Maximovich Litvinov (1876–1951), was the Soviet Union’s People’s Commissar for Foreign Affairs from 1930 to 1939. . . From 1941 to 1943 he was Soviet Ambassador to the United States” (780n).

Channon considered Litvinov a loathsome creature, but later that month he dines “at Maurice de Rothschild’s, a dinner of seventeen—a rich congestionné house. . . . He lives with a young Jewess who is either his daughter, or adopted child, or mistress or all three!! [She was his mistress] . . . Everyone a touch tipsy with Rothschild wine . . . Even Maurice, our fat, sensual, slobbery, lecherous host is relieved that war is off! Or at least postponed” (924).

It is obvious that the common Jewish phenotype does not appeal to Channon’s aesthetic. While visiting his friend and former classmate at Oxford Prince Paul of Yugoslavia, he dines with the King of Bulgaria. “He looks a Jew, but is really trés Coburg, trés Orleans with the unpleasant traits of both houses” (931). So in appearances, manners and politics, Channon and his crowd find Jews objectionable, but they offered little resistance to their growing wealth and power.

During the mid to late 1930s, British elites and the public generally were divided in their attitudes toward the Third Reich. The pro-German group that Channon supported became known as appeasers. Appeasement was an unfortunate label. It implies weakness and acquiesce. Rapprochement, realignment, readjustment, or reconciliation would have been better terms. As today, the Left possesses greater language skills and have been able to weaponize words, while the Right often has little feeling for language. In any case by the mid-30s many on the Right saw a powerful, prosperous Germany in central Europe as an asset. Channon believed that an alliance with Germany would be the best policy for Britain and for Europe. In September 1935 he wrote: “My secret [poorly kept secret] sympathies are ever with autocracies, and I’d rather have the Nazi-ism and Fascism on my side than Russian Soviets or tense, nervy croaking French Frogs. We seem not to know where our interests lie” (470). It is a bit ironic that Channon, who spent 1917–18 in France aiding the Allied war effort and who majored in French at college, had become anti-French by the mid-30s.

The era of good feeling between Britain and the Third Reich perhaps peaked during the Berlin Olympic Games in August 1936. The Channons and a number of other MPs and their wives were guests of the German government. Chips was not much of a sports fan, but he loved the lavish parties and the mass spectacles the regime provided. On August 6, their first day at the games, the crowds at the stadium were enthusiastic—ecstatic when Hitler arrived. Although the Fuhrer was physically unimposing, “One felt one was in the presence of some semi-divine creature” (557).

That evening the Channons attended a state banquet at the Berlin Opera House. The official hostess “Frau Göring, a tall, nearly naked, handsome woman was the principal figure and moved about amongst an obsequious crowd of royalties and ambassadors” (558). Two days later, Chips and Honor were the guests of Joachim von Ribbentrop, the German ambassador to Great Britain, later foreign minister. Attendees at the large luncheon included Lady Chamberlain, wife of the future prime minister.

On August 10, Channon’s trip included a visit to a “labour camp.” As far as I can tell, this is the only instance where editor Simon Heffer’s scholarship fails him. Heffer, a well-known British journalist and historian, is considered a conventional conservative by UK standards. His thousands of footnotes are indispensable in identifying the people and events referred in the diaries. In a footnote Heffer suggests that Channon visited a Nazi prison camp that had been fixed up, a sort of Potemkin village, for the benefit of foreign visitors. It is obvious from Chips’ description that what he visited was a Reich Labor Service camp. Such a camp was comparable to a Civilian Conservation Corps camp established during the same period in America.

Channon writes that “the camp looked tidy, even gay, and the boys, all about 18, looked like the ordinary German peasant boy, fair, healthy, and sunburned. They are taught the preliminary military drills, gardening, etc., and health and strength are built up. They were all smiling and clean. . . . For 6 months they lived there, and all classes are mixed, which is an excellent system, its purpose is to wipe out class feeling, which has become practically non-existent in Germany” (563). Heffer claims that “The impression Channon had from his visit was entirely manipulated and bogus” (footnote, 562). Incredibly, none of the mainstream reviews picked up on Heffer’s editorial mistake.

Channon is in love with the new Germany. The next day, after another excursion to the countryside, he writes: “In Germany joys are simple, sun and water bathing, Wurst and beer, all pleasant, all attainable for little. What a country. It stirs me so sharply” (563). He has a “preference for the Teutonic races. . . . There is a common blood affinity between us and the Germans and Austrians. I like their lusty warm-blooded love of country, children, dogs, power—and a thousand other reasons” (563). In the following days the Channons attend formal dinners at the Ribbentrops, the Görings (with 700-800 guests), and Dr. and Magda Goebbels’ Sommerfest. The closing ceremonies were on August 16. “The crowds were enormous, and really amazingly well controlled . . . there were processions, the orchestra played, Hitler rose, the great torch faded out, the crowd 140,000-strong sang ‘Deutschland über Alles’, with arms uplifted. There was a shout, a speech or two, night fell and the Olympic Games, the great German display of power and bid for recognition, was over. Mankind has never staged anything so terrific, or so impressive “(569). Exhausted from all parties and ceremonies the Channons left Berlin on August 18th and headed for the Austrian Alps for a quiet vacation.

While Chips was wowed by National Socialist Germany what he really wanted was a Hohenzollern restoration! The ideal scenario for him was for Hitler to be given a green light to move east and smash Bolshevism. Then, after the Fuhrer’s death or retirement, Channon’s friend Fritzi, Friedrich of Prussia, Grandson of Kaiser Wilhelm II, would become ruler of an enlarged German empire.

It is not possible to tell from the diaries how strong and widespread pro-German sentiments were at the time. Obviously Winston Churchill and some other MPs were opposed to a resurgent of Germany. From 1936 onward Channon notes Churchill’s increasing animosity towards the Third Reich. Was he working for Jewish interests as some have charged? Or did he simply not want a strong state in central Europe to rival British influence on the continent? In May 1936, after attending a play the Channons, Churchill, and some French and German guests had “sandwiches and drinks. The French Ambassador, Durckheim [a German diplomat] and Winston Churchill had a conversation which was really rather unpleasant, as Winston attacked Germany” (516). In July of 1937 Channon writes that Churchill’s “fear and dislike of [Germans] amount to an obsession, and threaten to seriously to undermine his judgement” (728). It is not an exaggeration to say that by 1938 Churchill wanted war.

A few additional words on Churchill: Already in early 1936 Channon identifies him as a prime mover in the anti-German group. Pat Buchanan, in the work cited above, also sees Churchill as the one most strongly pushing for confrontation with Germany. Churchill, of course, was not a man on the Left. He was a Tory, a conservative, an aristocrat, and an imperialist. Despite his skillful rhetoric he, at times, exercised monumentally poor judgement as the graves at Gallipoli attest. Channon wrote in 1938: “Is my world collapsing? Winston as PM would be worse than war. The two together would mean the destruction of civilization” (933). To paraphrase Buchanan, Churchill’s Pyrrhic victory over Germany in 1945 lost Britain its empire and lost the West the world. It is poetic justice that in 2020, a woke mob that he helped make possible, vandalized his statue in Parliament Square.

In March 1938 Channon “had a sparring match with [fellow MP] Harold Nicolson who was in a rage. Like all old women, he is having a change of life. His hatred of Germany is fanatical” (832). Several months later Channon reports that “Simon Harcourt-Smith [a career diplomat] tells me the Foreign Office is red, is trying to sabotage Halifax” who is trying to accommodate Germany. More about Lord Halifax below. At one point, Channon sees more grassroots support for Germany than elite support. “The Foreign Office, the ‘intelligentsia’, London society, Bloomsbury and a very large section of the [House of Commons] are pro-French, but the country as a whole is pro-German” (543).

The diaries record many pro-German contacts Channon had during the 1935–1938 period. To start at the top, Channon was friends with King Edward VIII who had a very positive attitude toward the new Germany. Unfortunately, he also had a very short reign, and abdicated in December 1936 in order to marry Wallis Simpson, a twice divorced American woman—another instance of a royal insisting on marrying an unsuitable mate. Earlier that year Chips had lunch with Joachim von Ribbentrop and his wife at a “pan-German festival” (519). He notes that Frau von Ribbentrop wore no makeup in the new German style. A few weeks later: “The Londonderrys [Charles Stewart, 7th Marquis of Londonderry] are very pro-German; and, indeed who isn’t?—except the Coopers [Alfred Duff Cooper, 1935 Secretary of State for War, 1937 First Lord of the Admiralty]” (519). Another of Chips’ friends, Arthur Charles Wellesley, 5th Duke of Wellington, “was a committed pro German, and a member of the Anglo-German Fellowship” (528n).

In November 1937 Edward Wood, Lord Halifax, attended the International Hunting Exhibition in Berlin hosted by Hermann Göring. Incidentally, the racial ecologist and sportsman Madison Grant was also invited and planned to attend this event, but sadly fell ill and died shortly before the opening. Although born with only one hand, Halifax, with the help of a prosthetic, became a skilled equestrian and marksman. He went to Germany as unofficial deputy foreign secretary (he became Foreign Secretary the following year). After the exhibition, he met with Hitler at Berchtesgaden. There he told the Führer that Prime Minister Chamberlain would not be opposed to Anschluss with Austria or to the transfer of Sudetenland and Danzig to Germany as long as it was accomplished peacefully. A couple weeks after his return Halifax told Chips that “he liked all the Nazis, even Goebbels! whom nobody likes. He was much impressed, interested, and amused by the visit” (786).

The diary identifies a number of other pro-German personalities of the time. Neville Meyrick Henderson, who was British ambassador to Germany (1937–1939) was supportive of the new Germany. Channon writes: “He is pro-German, anti-French, anti-Jew, pro-Italian, and, indeed thinks along the lines I do” (746). There was also some support from the British press such as George Ward Price, foreign correspondent for the Daily Mail, and Geoffrey Dawson, editor of The Times. From the pulpit there was Dean William Ralph Inge of St. Paul’s Cathedral and former professor of divinity at Cambridge. “He was a strong advocate of eugenics and nudism and rejected democracy, fearing it would bring mob rule” (877n).They don’t make clergy like that anymore!

So what happened? Why did Britain declare war on Germany in September 1939? This journal ends on September 30, 1938 with the signing of the Munich Accords. The next volume is due out later this year. A very rough sketch of the path to war sees Germany occupying Prague in March 1939. In response, Britain pledges to guarantee Poland’s sovereignty. Britain knew they did not have the means to protect Poland, but they hoped to deter German expansion. If not, the treaty would be a tripwire for war. Hitler wagered that his invasion of Poland would not trigger a wider war which he did not want. Both sides gambled, both sides lost.

Channon, as mentioned earlier, wanted Britain to ally with Germany, giving the latter a free hand in the east. But he was a backbencher with little official authority. He did, however, have connections. The Foreign Secretary, Lord Halifax, was his wife’s uncle. Chips was also parliamentary assistant to Rab Butler, Under Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs. Butler opposed war in September 1939 and was willing to sacrifice Polish independence to avoid a wider conflict. On the other side, Hitler’s mistake was to force the pace of events, to press forward too far too fast, and to risk everything on one roll of the dice. Commentators as diverse as Sir Arthur Keith and Henry Kissinger believe that if the Fuhrer had had a little more patience and played the long game he would have achieved his goals.

Although many academic historians would disagree, most laymen believe that the study of history should have some utility. So what is useful in reading Channon’s diaries? Besides moaning about what the leaders of the time should have done to avoid a disastrous internecine struggle, we can see from these journals that the values espoused by National Socialist Germany resonated with a significant segment of British society. Today the establishment considers these values be to so reprehensible as to be indications of extreme moral depravity.

As for a recommendation: These diaries are most suitable for serious students of interwar Britain. Much of the partisan politics of the era are of limited interest today. There is quite a bit of material on Edward’s abdication for royal watchers. A good deal of the text is taken up with Channon’s personal and social life. At times his relationship with Honor has a soap opera quality. As for Henry Channon the man, I found it hard not to have a certain affinity and admiration for him. Sure, he was a snob, a social climber, a name dropper, but he was no dilettante. He knew history and was a perceptive observer of people and events.

[1] Patrick J. Buchanan, Churchill, Hitler and the Unnecessary War: How Britain Lost Its Empire and the West Lost the World (New York: Crown Books, 2008).