Minority Malice: The Curious Case of Daniel Quilp

Chaucer, Shakespeare and Dickens are perhaps the three central figures of English literature. Representing respectively poetry, drama and prose, they have been hugely influential for centuries, read, analysed and quoted by countless millions around the world in every language from English and Afrikaans to Hindi and Mandarin.

Viral Vectors

But in modern times all three of them have also been condemned as vectors of an ancient and deadly ideological virus: anti-Semitism. In the Prioress’s Tale (c. 1390), Chaucer wrote of a saintly Christian child murdered by evil Jews. In The Merchant of Venice (c. 1596), Shakespeare brought life to Shylock, a vengeful and cunning Jewish merchant. In Oliver Twist (1838), Dickens portrayed Fagin, the corrupter, tutor and fence to a gang of child-thieves:

In a frying-pan, which was on the fire, and which was secured to the mantelshelf by a string, some sausages were cooking; and standing over them, with a toasting-fork in his hand, was a very old shrivelled Jew, whose villainous-looking and repulsive face was obscured by a quantity of matted red hair. He was dressed in a greasy flannel gown, with his throat bare; and seemed to be dividing his attention between the frying-pan and the clothes-horse, over which a great number of silk handkerchiefs were hanging. (Oliver Twist, chapter 8)

Dickens began his hate-stereotype as he meant to go on: sluicing Fagin with millennia’s-worth of gentile malice, from the red hair of Judas to the venality and ruthlessness ascribed to Jewish moneylenders in the Middle Ages. Fagin looks villainous because he is villainous: selfish, cunning, and manipulative. And his villainy is inseparable from his race and religion. Dickens refers to him as “the Jew” more than three hundred times in early editions of Oliver Twist.

Charles Dickens (1812–1870)

Because Fagin is a hate-stereotype, there is no need to ask whether he also is an accurate portrayal of how some Jews behaved in Victorian times. Some scholars have claimed that Fagin was based on the Jewish criminal Ikey Solomon, whom Dickens observed when he worked as a journalist. Dickens himself claimed: “Fagin in Oliver Twist is a Jew, because it unfortunately was true of the time to which that story refers, that that class of criminal almost invariably was a Jew.”

These claims are irrelevant. As I pointed out in “Reality is Racist,” if an accusation invokes a hate-filled stereotype, the accusation can be dismissed out of hand. All decent people know this. When the playwright Alan Bennett came across a British cartoon from World War II that portrayed “black marketeers” as “strongly Semitic in features,” he condemned it instantly as unacceptable, without pausing to consider whether it was based on a statistical reality.

Hidden Hate

And it is decent people like Bennett and his fellow goodthinkers whom I want to address in this article. I want to alert them to the possibility that Dickens created another anti-Semitic hate-stereotype — one that has, unlike Fagin, gone unnoticed and uncondemned in the many years since it first appeared.

A modern writer who used a character like Fagin would be of course be liable to prosecution and even imprisonment in most Western countries. Even in the nineteenth century Dickens was strongly criticized: one Jewish correspondent said that Fagin “encouraged a vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew.” Dickens was influenced by this criticism. He is known to have reduced references to Fagin’s Jewishness in later editions of Oliver Twist, and in his final novel, Our Mutual Friend (1865), he created a highly positive Jewish character called Riah (Hebrew for “friend”).

But he may also have resented the criticism and responded to it by creating an implicit Jewish villain in a novel that closely followed Oliver Twist, which was first serialized in 1837. Dickens’ character Daniel Quilp appears in The Old Curiosity Shop, which was first serialized in 1840. Even people who haven’t read the book may know of it through Oscar Wilde’s alleged remark: “One would have to have a heart of stone to read the death of little Nell without dissolving into tears…of laughter.” Wilde was right: Little Nell is the book’s insipid and implausible heroine, quite literally too good for this world.

The Demonic Dwarf

But Daniel Quilp, the book’s vivid and irrepressible villain, proves that Dickens had a literary genius far beyond anything Wilde could achieve. For me, Dickens is rivalled only by Evelyn Waugh as a creator of characters, particularly of villains, eccentrics and grotesques. Both writers had an almost magical ability to turn language into life: their best characters live and breathe on the page. Quilp is one of the finest — or foulest — examples of Dickens’ literary genius. When he first appears, he is described as

an elderly man of remarkably hard features and forbidding aspect, and so low in stature as to be quite a dwarf, though his head and face were large enough for the body of a giant. His black eyes were restless, sly, and cunning; his mouth and chin, bristly with the stubble of a coarse hard beard; and his complexion was one of that kind which never looks clean or wholesome. But what added most to the grotesque expression of his face was a ghastly smile, which, appearing to be the mere result of habit and to have no connection with any mirthful or complacent feeling, constantly revealed the few discoloured fangs that were yet scattered in his mouth, and gave him the aspect of a panting dog. His dress consisted of a large high-crowned hat, a worn dark suit, a pair of capacious shoes, and a dirty white neckerchief sufficiently limp and crumpled to disclose the greater portion of his wiry throat. Such hair as he had was of a grizzled black, cut short and straight upon his temples, and hanging in a frowzy fringe about his ears. His hands, which were of a rough, coarse grain, were very dirty; his fingernails were crooked, long, and yellow. (The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter III)

The character then introduces himself: “Quilp is my name. You might remember. It’s not a long one — Daniel Quilp.” Daniel is a Biblical Hebrew name meaning “God is my Judge” but what is the significance of the invented surname Quilp? I’d suggest it’s a kind of verbal chord blending three concepts: Quick-Ill-Imp. Quilp is very fast in thought and deed. He’s called an “ill weed” by his wife’s mother, to whom he is an “impish son-in-law” (ch. IV). His diabolical aspect is underlined by Dickens’ repeated references to Quilp enjoying strong tobacco, flourishing in stiflingly smoky places, and drinking boiling liquids without suffering any harm.

Quilp as Anti-Semitic Satire

But what about Quilp’s Jewish aspect? Dickens makes no explicit reference to his race, but I think there are strong clues in the text:

Mr Quilp could scarcely be said to be of any particular trade or calling, though his pursuits were diversified and his occupations numerous. He collected the rents of whole colonies of filthy streets and alleys by the waterside, advanced money to the seamen and petty officers of merchant vessels, had a share in the ventures of divers mates of East Indiamen, smoked his smuggled cigars under the very nose of the Custom House, and made appointments on ’Change [Stock Exchange] with men in glazed hats and round jackets pretty well every day. (The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter 4)

Quilp is a devious rent-collector and money-lender who describes his own nose as “aquiline” (ch. 49). Like Fagin, he is “villainous-looking,” “repulsive” and “dirty.” He has “matted hair” just like Fagin (ch. 67). Dickens describes him “rubbing his hands so hard that he seemed to be engaged in manufacturing, of the dirt with which they were encrusted, little charges for popguns” (ch. 4). Like Fagin, he is endlessly greedy for money: when he thinks Little Nell’s grandfather has a “secret store of money,” “the idea of its escaping his clutches overwhelmed him with mortification and self-reproach” (ch. 13). Where Fagin is continually called “the Jew,” Quilp is continually called “the dwarf” — more than two hundred times, in fact. And while Quilp has “black eyes,” his bullied and intimidated wife is a “pretty little, mild-spoken, blue-eyed woman” (ch. 4).

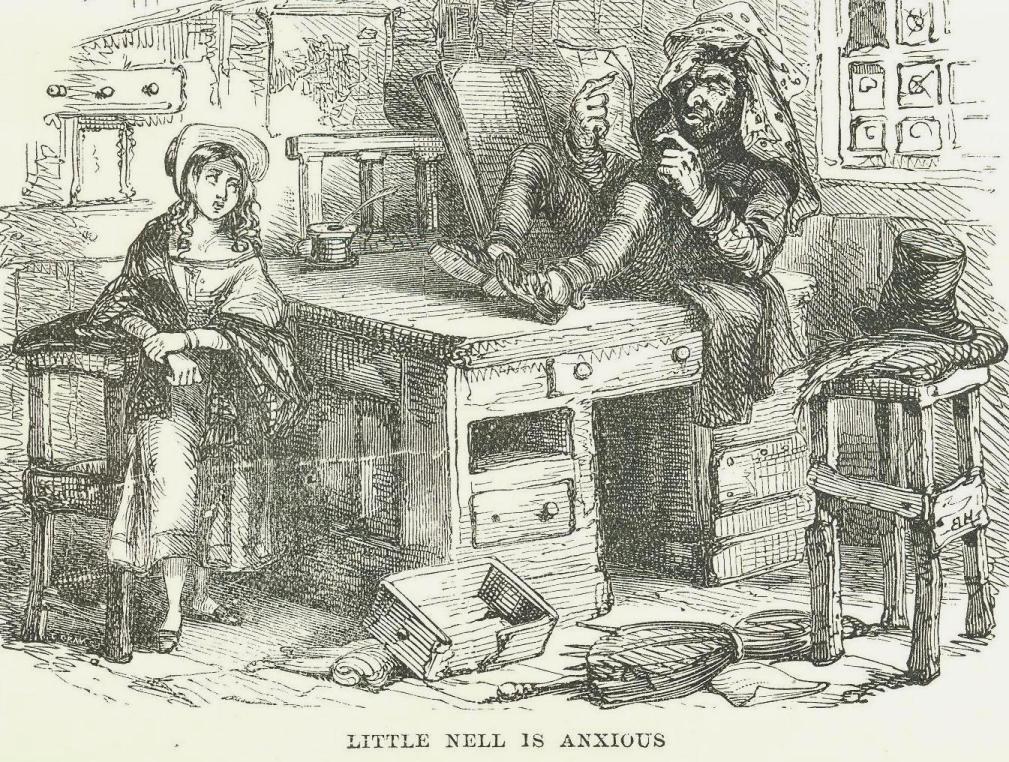

Quilp with Little Nell

Little Nell is pretty and has blue eyes too (ch. 1). She is only thirteen, but Quilp is plotting to make her “Mrs Quilp the second, when Mrs Quilp the first is dead” (ch. 6). Dickens’ friend and first illustrator George Cattermole (1800–68) may have thought this suggested Jewish lust after blond, blue-eyed, non-Jewish women, because he unmistakably portrayed Quilp as a Jewish stereotype: hook-nosed, swarthy and scowling. Dickens did not object and I would suggest that the illustration exactly captured his intentions. As others have suggested, I am suggesting that Daniel Quilp was implicitly written as a Jewish villain.

Minority Malice

Dickens may have resented the criticism he received for his portrayal of Fagin in Oliver Twist. He had been accused of encouraging “vile prejudice,” when his intention, as always, had been to expose a reality in the hope of reforming it. Jewish criminals like Fagin really existed, just as brutal thieves like Bill Sykes and despairing prostitutes like Nancy did. Dickens had met and closely observed all three kinds of people. Why should he be condemned for speaking the truth about Fagin and not about Sykes and Nancy?

And why should Jews be regarded as harmless or beyond criticism simply because they were a minority? Dickens may have satirized his Jewish critics by making Quilp an expert in dissimulation:

Mr Quilp now walked up to front of a looking-glass, and was standing there putting on his neckerchief, when Mrs Jiniwin [his mother-in-law] happening to be behind him, could not resist the inclination she felt to shake her fist at her tyrant son-in-law. It was the gesture of an instant, but as she did so and accompanied the action with a menacing look, she met his eye in the glass, catching her in the very act. The same glance at the mirror conveyed to her the reflection of a horribly grotesque and distorted face with the tongue lolling out; and the next instant the dwarf, turning about with a perfectly bland and placid look, inquired in a tone of great affection.

“How are you now, my dear old darling?”

Slight and ridiculous as the incident was, it made him appear such a little fiend, and withal such a keen and knowing one, that the old woman felt too much afraid of him to utter a single word. (The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter 4)

“I don’t know how he came or why, my dear,” rejoined Mrs Nubbles [Kit’s mother], dismounting with her son’s assistance, “but he has been a-terrifying of me out of my seven senses all this blessed day.”

“He has?” cried Kit.

“You wouldn’t believe it, that you wouldn’t,” replied his mother, “but don’t say a word to him, for I really don’t believe he’s human. Hush! Don’t turn round as if I was talking of him, but he’s a squinting at me now in the full blaze of the coach-lamp, quite awful!”

In spite of his mother’s injunction, Kit turned sharply round to look. Mr Quilp was serenely gazing at the stars, quite absorbed in celestial contemplation.

“Oh, he’s the artfullest creetur!” cried Mrs Nubbles. “But come away. Don’t speak to him for the world.” (The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter 48)

But Quilp is also a way for Dickens to convey some shocking ideas about minorities in general. As a dwarf, Quilp belongs to a “visible minority” and is subject to majority prejudice: he is called “a little hunchy villain and a monster” by his mother-in-law and “an uglier dwarf than can be seen anywheres for a penny” by Kit, one of the book’s virtuous characters. In liberal ideology, these accusations should be grossly unjust or unfair. Quilp should be a saintly victim, displaying deep solidarity with other vulnerable communities and individuals.

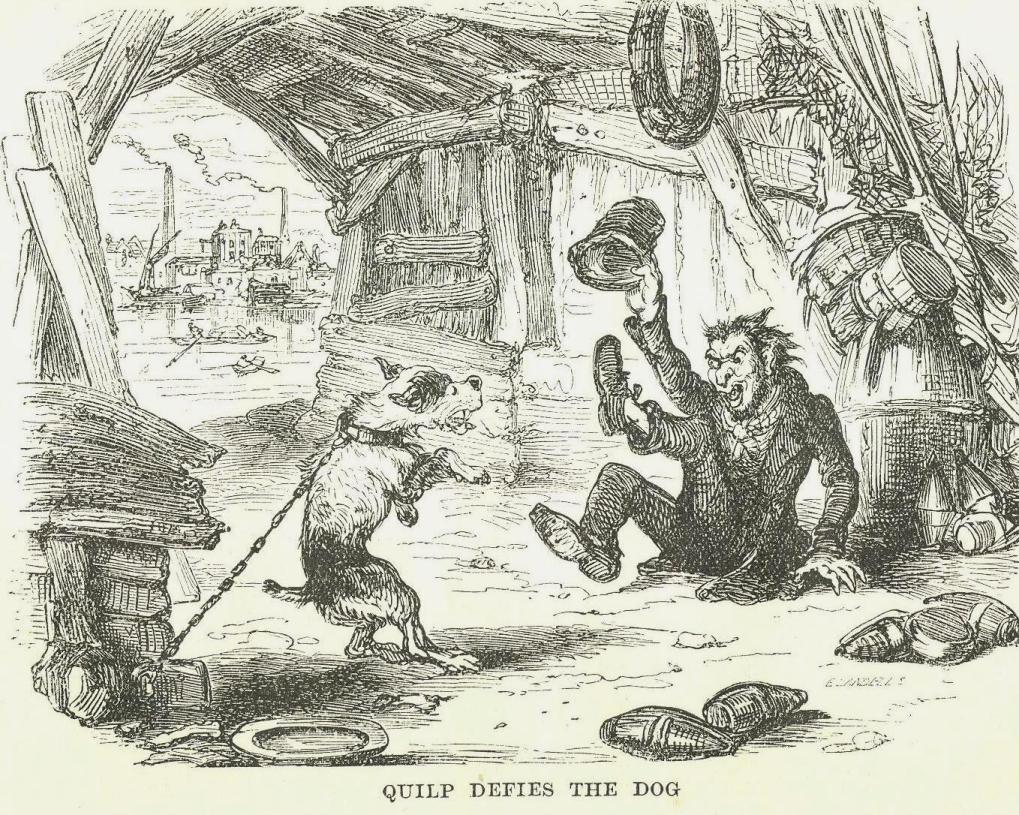

Quilp teases a dog

But he isn’t and he doesn’t. He provokes hostility by his own behaviour and malice. Far from sympathizing with the weak and helpless, he takes great delight in tormenting them. His chief pleasure in life is bringing pain and misery to others. And he is well capable of doing so. He is highly intelligent, cunning and perceptive. Despite his small size, he is also very strong and physically adept. He doesn’t hesitate to use his advantages. He keeps his wife up all night to watch him smoke and drink, grinning with delight when she makes “some involuntary movement of restlessness or fatigue” (ch. 4). He beats and bruises the boy who keeps watch on “Quilp’s Wharf” (ch. 6). He bullies Kit’s mother (ch. 48) and nearly succeeds in having Kit himself transported to an overseas penal colony on a trumped-up charge of theft (ch. 60). He tricks Little Nell and her grandfather out of their home and forces them out of London (ch. 12), thereby bringing about both their deaths.

Dickens’ Self-Censorship

But the full extent of his villainy is not apparent in the published text of The Old Curiosity Shop, because Dickens suppressed something that appeared in the manuscript. Here is the scene in which Quilp meets a starved and mistreated servant-girl who works for two of his confederates, the crooked lawyer Sampson Brass and his sister Sally:

“Where do you come from?” he said [to the servant] after a long pause, stroking his chin.

“I don’t know.”

“What’s your name?”

“Nothing.”

“Nonsense!” retorted Quilp. “What does your mistress call you when she wants you?”

“A little devil,” said the child.

She added in the same breath, as if fearful of any further questioning, “But please will you leave a card or message?”

These unusual answers might naturally have provoked some more inquiries. Quilp, however, without uttering another word, withdrew his eyes from the small servant, stroked his chin more thoughtfully than before, and then, bending over the note [he has written to the Brasses] as if to direct it with scrupulous and hair-breadth nicety, looked at her, covertly but very narrowly, from under his bushy eyebrows. The result of this secret survey was, that he shaded his face with his hands, and laughed slyly and noiselessly, until every vein in it was swollen almost to bursting. Pulling his hat over his brow to conceal his mirth and its effects, he tossed the letter to the child, and hastily withdrew.

Once in the street, moved by some secret impulse, he laughed, and held his sides, and laughed again, and tried to peer through the dusty area railings as if to catch another glimpse of the child, until he was quite tired out. (The Old Curiosity Shop, chapter 51)

According to Claire Tomlin’s biography of Dickens, “a note in the manuscript suggested that she [the servant-girl] was the [illegitimate] daughter of … Sally Brass and Quilp.” Only slight hints of this survive in the published text, but it casts Quilp’s behaviour in an even worse light. He is laughing with delight at the suffering and hopeless situation of his own daughter, which he is rich enough to end immediately.

Quilp’s Spying

Dickens’ understanding of human psychology is accurate: there are people who behave like that. In liberal ideology, however, Dickens is committing blasphemy. How dare he suggest that Quilp, one victim of majority hate, can take delight in the suffering of another victim? Daniel Quilp is addicted to spying: Dickens describes him as casting “a keen glance around which seemed to comprehend every object within his range of vision, however small or trivial” (ch. 3). He uses spyholes (ch. 49), eavesdrops at every opportunity (ch. 4, ch. 6 and passim), and offers “large rewards” for “any intelligence” of Little Nell and her grandfather (ch. 48) when they evade his plots. The more he knows, the more he has power over those whom he wishes to harm and the better he can protect himself from retribution. In short, he has the paranoia and vigilance of a minority that anticipates a hostile response to its own bad behaviour.

The End of Quilp

Even when his own espionage fails him, he is warned by Sally Brass that her brother has exposed the plot to ruin Kit. The authorities are closing in on him as he camps out in his riverside counting-house, companioned by what he calls those “fine stealthy secret fellows,” that is, the rats. Quilp tries to escape arrest, but a heavy fog has fallen and he loses his way, falls in the Thames, and drowns. It’s a disappointingly banal end for someone who is, like Fagin and Shylock, one of the greatest villains in English literature.

Unlike Fagin and Shylock, however, Quilp has never been called an anti-Semitic libel. Nevertheless, I believe that he is implicitly Jewish and that Dickens was creating an anti-Semitic stereotype: Quilp is highly intelligent but also highly malicious. Just as Dickens concealed the parentage of the servant-girl, fearing that he would shock his audience, so he concealed the race of Quilp, not wanting to be accused again of “vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew,” as he had been after the serialization of Oliver Twist. But his illustrator George Cattermole clearly read the textual hints — or followed Dickens’ private instructions — and drew Quilp as a Jew.

Another Outbreak of Anti-Semitism

Those who doubt this thesis about Quilp should consider that Dickens was explicitly anti-Semitic in Great Expectations. That novel was first serialized in 1860, more than two decades after Oliver Twist first began to appear. When the protagonist Pip travels to London, he learns how popular his guardian, the lawyer Jaggers, is with the criminal classes. Among those eager for Jaggers’ help is a lisping, highly strung Jew whose brother has been charged with dealing in stolen silver-plate:

There was a red-eyed little Jew who came into the Close while I was loitering there, in company with a second little Jew whom he sent upon an errand; and while the messenger was gone, I remarked this Jew, who was of a highly excitable temperament, performing a jig of anxiety under a lamp-post and accompanying himself, in a kind of frenzy, with the words, “O Jaggerth, Jaggerth, Jaggerth! all otherth ith Cag-Maggerth, give me Jaggerth!”

These testimonies to the popularity of my guardian made a deep impression on me, and I admired and wondered more than ever. …

No one remained now but the excitable Jew, who had already raised the skirts of Mr. Jaggers’s coat to his lips several times.

“I don’t know this man!” said Mr. Jaggers, in the same devastating strain: “What does this fellow want?”

“Ma thear Mithter Jaggerth. Hown brother to Habraham Latharuth?” [i.e., Abraham Lazarus]

“Who’s he?” said Mr. Jaggers. “Let go of my coat.”

The suitor, kissing the hem of the garment again before relinquishing it, replied, “Habraham Latharuth, on thuthpithion of plate.”

“You’re too late,” said Mr. Jaggers. “I am over the way.”

“Holy father, Mithter Jaggerth!” cried my excitable acquaintance, turning white, “don’t thay you’re again Habraham Latharuth!”

“I am,” said Mr. Jaggers, “and there’s an end of it. Get out of the way.”

“Mithter Jaggerth! Half a moment! My hown cuthen’th gone to Mithter Wemmick at thith prethent minute, to hoffer him hany termth. Mithter Jaggerth! Half a quarter of a moment! If you’d have the condethenthun to be bought off from the t’other thide–at hany thuperior prithe!—money no object!—Mithter Jaggerth—Mithter—!”

My guardian threw his supplicant off with supreme indifference, and left him dancing on the pavement as if it were red hot. (Great Expectations, chapter 20)

That is not a positive portrait of Jewish behaviour or psychology. It also proves that Dickens was partly unrepentant after the criticism he received for Oliver Twist. When some years had elapsed, he again and openly encouraged “vile prejudice against the despised Hebrew.” To my mind, that strengthens the possibility that he secretly expressed that “vile prejudice” in The Old Curiosity Shop, published soon after Oliver Twist.

“Wholesome fear…”

But whether he was creating an overtly Jewish villain in Fagin or, as I would argue, a covertly Jewish villain in Daniel Quilp, Dickens was motivated not by hate or prejudice, but by realism and personal observation. Minorities and outsiders are not automatically saintly or automatically victims of the majority. Indeed, this simple fact is the main reason why Whites are making a catastrophic mistake in allowing themselves to become minorities. Despite his small size and isolation, Daniel Quilp is perfectly capable of bringing misery and ruin to those around him. As Dickens notes: “the ugly creature contrived by some means or other — whether by his ugliness or his ferocity or his natural cunning is no great matter — to impress with a wholesome fear of his anger, most of those with whom he was brought into daily contact and communication” (ch. 4).

Reality and Reform

In The Old Curiosity Shop, Dickens commits blasphemy against liberal ideology. He was a literary genius, one of the most acute and sympathetic observers of human behaviour who ever lived, but he did not believe in the worship of minorities or the demonization of majorities. Instead, he thought that we should look at human beings and see them as they are. When they behave badly, they should be criticized for it, whatever their race or station in life. If we’re unable to expose reality, we’re also unable to reform it.

Daniel Quilp, one of Dickens’ greatest villains, certainly knew that truth, which is why he concealed his own activities while spying constantly on those of others. The parallels with the behaviour of the hostile elite should be obvious. But the hostile elite is no more invincible than Daniel Quilp was. When reality is exposed, reform can follow. That is the task of websites like the Occidental Observer and movements like the Alt Right.

Comments are closed.