The Jewish Question: Suggested Readings with Commentary Part Two of Three: The Nineteenth Century

Thomas Macaulay

Mirroring developments in Germany, by 1831 the Jewish Question, in the form of the desirability of granting Jews admission to Parliament, had also become a topic of fevered discussion in Britain. One of the most fascinating published opinions produced during this period was Civil Disabilities of the Jews, an essay produced by the historian, essayist and politician Thomas Macaulay (1800—1859). Ostensibly the argument of a classic Liberal in favor of extending political power to Jews, the text is in fact complex and thus more significant. Macaulay’s argument in favor of admitting Jews to Parliament reveals much about the extent and nature of Jewish power and influence in Britain at that time. He viewed emancipation as a means of ‘keeping the Jews in check.’ For example, he insisted that “Jews are not now excluded from political power. They possess it; and as long as they are allowed to accumulate property, they must possess it. The distinction which is sometimes made between civil privileges and political power, is a distinction without a difference. Privileges are power.” Jews were thus already incredibly powerful in the form of civil privileges, and since political power was accompanied by a set of checks and balances, Macaulay’s theory was that admitting Jews into such a system could be a way of better controlling their power and influence.

Macaulay was aware of the role of finance as the primary force of Jewish power in Britain. He asked: “What power in civilized society is so great as that of creditor over the debtor? If we take this away from the Jew, we take away from him the security of his property. If we leave it to him, we leave to him a power more despotic by far, than that of the King and all his cabinet.” Macaulay responds to Christian claims that “it would be impious to let a Jew sit in Parliament” by stating bluntly that “a Jew may make money, and money may make members of Parliament. … The Jew may govern the money market, and the money market may govern the world. … The scrawl of the Jew on the back of a piece of paper may be worth more than the word of three kings, or the national faith of three new American republics.” Macaulay’s insights into the nature of Jewish power at that time, and his assertions that Jews had already accumulated political power without the aid of the statute books, are quite profound. Yet his reasoning — that permitting Jews into the legislature would somehow offset this power, or make it accountable — seems pitifully naive and poorly thought out. Nevertheless, the context and content of his famous essay should be regarded as essential reading.

As well as political challenges to the move for increased Jewish power, cultural challenges were also prominent. As part of their effort to gain influence within the bureaucratic machinery of the modern state, Jews constructed intellectual groupings designed to ‘prove’ that Jews had embraced the principles of the Enlightenment to the same extent as their hosts. These intellectual groups, of which Moses Mendelssohn can be considered as something of a pioneer, developed a system of pseudo-scholarly apologetics — Wissenschaft des Judentums or the Science of Judaism. The activities of this group of Jewish intellectuals began to peak in the second decade of the nineteenth century, especially following the founding of the Center for Culture and the Science of Judaism in Berlin in 1819. Some of the most important productions of the group were apologetic accounts of the Jewish past, which included factually dubious accounts about how Jews were ‘forced’ into money-lending and other socially despised behaviors. Many of the modern regurgitations of ideas like this by organizations like the ADL, or even mainstream Jewish historians, can be traced directly to the “scholars” of the Wissenschaft des Judentums. This effort at cultural reinvention provoked a different texture of reaction from non-Jewish intellectuals, and an excellent example in this regard is Jakob Friedrich Fries (1773-1843).

In 1816 Fries, an extremely popular lecturer in philosophy at the universities of Jena and Heidelberg, published a small text titled On the Danger to the Well-Being and Character of the Germans Presented by the Jews. The book was a reaction against the development of a series of apologetics presenting Jews as a downtrodden and victimized group. Fries described as a “prejudice” the idea that “Jews were persecuted by us with blind rage and unjust religious zeal during the Middle Ages.” Rather, Jews aroused hostility because “princes almost always favored them too much,” and they made their living, out of choice, as “insidious second-hand dealers and exploiters of the common people.” Fries argued that the extension of civic rights would not alter the behavior of the Jews because empirical evidence was available in lands where Jews already enjoyed such rights and their socio-economic and political behavior was indistinguishable from that of Jews in the German states. Much like Macaulay, Fries saw money as the fulcrum on which Jewish influence gained its strength, and he warned that Jewish influence would always be highest in states with a strong central government and oppressive taxation.

Another important historiographical text of the same period was Heinrich Leo’s Geschichte des judischen Volkes (History of the Jewish People), published in 1828. Leo (1799–1878) had been a radical Leftist in his student days but became disillusioned with this form of politics after the high-profile murder of the aristocrat August von Kotzebue in 1819 by a student attached to revolutionary politics. He quickly came under the influence of philosopher Johann Gottfried Herder, developing an affinity for conservatism and romanticism. An ardent opponent of the extension of civic rights to Jews, Leo argued against the idea of historical Jewish victimhood and warned in History of the Jewish People that they possessed a “corroding intellect,” and explained that Jewish monotheism, as well as other qualities of Judaism and Jewish national character were the result of a peculiarly destructive reason.

A few historiographical examples aside, however, political statements were the norm throughout the nineteenth century, and the debate around the extension of ‘civic rights’ remained dominant. This was certainly the focus of The Jewish Mirror, (1821), by Hartwig von Hundt-Radowsky (1759–1835). Unlike many of the authors previously mentioned, Hundt-Radowsky was a journalist and political writer rather than a scholar or professional politician. The tone of The Jewish Mirror thus has a more polemical and sensational aspect to it. However, few works articulate in simple, emotional terms, the case of the Europeans against the encroachment of Jewish influence in their systems of government. Indeed, his appeal can be considered even from the modern perspective of opposition to mass immigration. Hundt-Radowsky writes: “Granting civic rights to Jews was an injustice perpetrated by the government against the non-Jewish inhabitants. The latter and their ancestors founded the state, defended and preserved it with their wealth, blood, and lives, against both internal and external enemies. Now, however, a class of morally and spiritually degenerate people (whom we shelter, and who have benefited from the state but never benefit it at all) is treated in the exact same manner that we are.”

One of the seminal texts which took a truly broad and nuanced view of the historical and contemporary interaction between Jews and Europeans is Bruno Bauer’s The Jewish Question (1843). Bauer (1809–1882) was a theologian, philosopher and historian, as well as a keen student of Hegel (leading to his own radical criticism of the New Testament). After being dismissed from a teaching position at Bonn on account of his radical ideas, Bauer turned to writing histories of the rise of Christianity as well as shorter pieces on contemporary politics and culture. Bauer was strongly opposed to ‘Jewish emancipation,’ for reasons he articulated at length in The Jewish Question. Bauer is essential reading for the incisiveness and occasional humor in his discourse. For example, he castigated the naive social justice warriors of his day for fighting against privilege while they “at the same time grant to Judaism the privilege of unchangeability, immunity, and irresponsibility.” All demands are made of the Germans while “the heart of Judaism must not be touched.”

To Bauer, Jews could not “feel at home in a world which they did not make, did not help to make, which is contrary to their unchanged nature.” Rather than conform to the state of the Gentiles, Jews would seek entry to the state only in order to adapt it for their own requirements and comfort. Like Fries, Bauer had little time for false narratives of historically oppressed Jewish communities. Jews had indeed suffered violence at times, but the cause of violence was Judaism itself — they suffered because of the negative effects of their selfish creed on others. It was “for their way of life and for their nationality that they were martyred. They were thus themselves to blame for the oppression they suffered, because they provoked it by their adherence to their law, their language, to their whole way of life. A nothing cannot be oppressed. Wherever there is pressure something must have caused it by its existence, by its nature. In history nothing stands outside the law of causality, least of all the Jews.”

Bauer also has some stinging comments to make on the more reckless egalitarianism of the Enlightenment. In particular, he argued against the idea that ‘rights’ are innate, writing that they instead come with certain requirements and responsibilities: “The idea of human rights was discovered for the Christian world in the last century only. It is not innate in man, it has rather been won in battle against historical traditions which determined the education of men until now. So human rights are not a gift of nature or of history, but a prize which was won in the fight against the accident of birth and against privilege which came down through history from generation to generation. Human rights are the result of education, and they can be possessed only by those who acquire and deserve them.”

Bauer’s commentary on the Jewish Question sparked a renewed controversy throughout Germany involving heated contributions from both sides of the debate. One of the contributors in the aftermath of Bauer’s publication was none other than Karl Marx (1818–1883) who published On the Jewish Problem in 1844. Describing Bauer’s analysis as “one-sided,” Marx further accuses Bauer of treating the Jewish problem as an exclusively religious question. To Marx, this is a weak approach because ‘the Jew’ is much more than an adherent of a religion: “What is the worldly basis of Judaism? Practical necessity, selfishness. What is the worldly culture of the Jew? Commerce. What is his worldly God? Money.” Marx thus argues that a society that abolishes the “presuppositions of commerce” would “have made the existence of the Jew impossible. His religious consciousness would dissolve like a thin vapor in the real life atmosphere of society.” Jews, in this reading, are thus mere victims of capitalism and circumstance. While lengthy and verbose, Marx’s On the Jewish Problem is not really any different in content or aims from the efforts of those behind the Wissenschaft des Judentums. Whereas these scholars argued that Jews were ‘forced’ into money-lending and were thus victims in that sense, Marx offers the apologetic that Jews are victims of capitalism and the presuppositions of commerce, and therefore ‘just like anyone else.’ The apologetic element of Marx’s text is quite cleverly disguised, and it has been mistakenly described as an anti-Semitic tract by many mainstream historians. Certainly, Marx is at times blunt in his use of language when discussing the Jewish fascination with money, but his over-arching thesis is of a kind that ultimately leads the discussion towards capital and away from a useful discussion of what makes Judaism and Jewish group behavior so antagonistic to surrounding populations. What Marx fails to address anywhere in his thesis is the blindingly obvious — the unique and very lucrative role of Jews within capitalism at all points in history. Despite its weaknesses, the text is worth studying even if only because of the historical significance of its author.

By the 1850s, ‘Jewish emancipation’ had become the norm throughout Western Europe. Even at the earliest stages, some of the figures who had previously issued warnings now felt that their admonishments had been vindicated. The rapid progression of Jews in parliaments, state bureaucracies, academic faculties, branches of culture, journalism, and finance was matched by increased Jewish critique of national cultures and the idea of the nation. An excellent example of the deeper origins of this ‘Culture of Critique’ is The History of Jews (in eleven volumes) by the Jewish intellectual Heinrich Graetz.

Heinrich von Treitschke

Rather than offer my own critique of Graetz, I refer readers instead to another valuable reading on the Jewish Question: Heinrich von Treitschke’s Ein Wort ueber unser Judenthum (A Word About Our Jewry). During 1879 and 1880 Treitschke (1834–1896), a renowned German historian, published a number of articles on the Jewish Question under this heading in the Preussiche Jahrbuecher, one of the most prestigious academic journals in Germany at that time (and which he edited). To Treitschke, the core of the Jewish Question was the contradictory stance of the Jews — claiming an absolute right to protect and preserve their particular national identity while also claiming the right to participate fully (or interfere) in the lives of other nations. Of particular annoyance to Treitschke was what he perceived to be a Jewish arrogance, a particularly obnoxious conceit that often manifested in the most vicious critique of the host culture, and the attempt by Jews to claim credit for any and all advancements achieved by those nations (on this see my analysis of a more modern example of the same phenomenon in relation to Spinoza). In this regard, Treitschke found ample material in the Jewish history of Heinrich Graetz:

A dangerous spirit of arrogance has arisen in Jewish circles and the influence of Jewry upon our national life has recently often been harmful. I refer the reader to The History of the Jews by Heinrich Graetz. What a fanatical fury against the ‘arch enemy’ Christianity, what deadly hatred of the purest and most powerful exponents of German character, from Luther to Goethe and Fichte! And what hollow, offensive self-gratification! Here it is proved with continuous satirical invective that the nation of Kant was really educated to humanity by the Jews only, that the language of Lessing and Goethe became sensitive to beauty, spirit, and wit only through [Jewish intellectuals] [Ludwig] Boerne and [Heinrich] Heine!

Treitschke’s critique of Jewish culture is damning. He argues that Jews share heavily in the guilt for “the contemptible materialism of our age.” All over Germany, from the cities to the villages, “we have the Jewish usurer.” While Jews do not occupy the top rank in art and science, they swell the third rank with “Semitic hustlers” who enjoy the support and promotion of their co-religionists in the media: “And how firmly this bunch of literateurs hangs together! How safely this insurance company for immortality works, based on the tested principle of mutuality, so that every Jewish poetaster receives his one-day fame, dealt out by the newspapers immediately and in cash, without delayed interest.” To Treitschke, “the greatest danger is the unjust influence of the Jews in the press.” The Jewish intellectual Boerne “was the first to introduce into our journalism the peculiar shameless way of talking about the fatherland in an off-hand manner and without any reverence, like an outsider, as if mockery of Germany did not cut deeply into the heart of every individual German.” While Treitschke doubted that there would ever be a solution to the Jewish Question, since “there has always been an abyss between Europeans and Semites,” he did assert that improvement would only come about if Jews “who talk so much about tolerance, became truly tolerant themselves and show some respect for the faith, the customs, and the feelings” of those they dwell among.

While Treitschke’s analysis was measured and typically academic, the same complaints he had made also gave rise to a more popular and emotional form of response. One was the Antisemiten-Katechismus (Anti-Semite’s Cathecism), published in 1883 by Theodor Fritsch. In this tome, Fritsch (1852–1933), a publicist and politician, printed an ethno-nationalist version of the ‘Ten Commandments’ which he believed would reduce frictions between Jews and the host population. In brief, they are calls to take pride in one’s ethnicity; to regard Jews as opponents; to “keep thy blood pure”; to help those of your own race; to have no social intercourse with Jews; to have no business relations with Jews; to refrain from adopting Jewish tactics and strategies in any walk of life; to refrain from using Jewish lawyers, doctors or teachers; to refuse all Jewish writings and opinions and keep them “from thy home and hearth”; and to refrain from engaging in any form of violence against Jews “because it is unworthy of thee and against the law. But if a Jew attack thee, ward off his Semitic insolence with German wrath.”

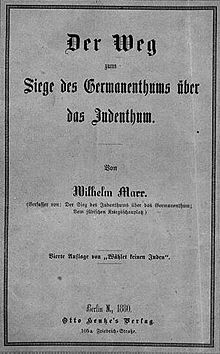

While the 19th century witnessed an outpouring of commentary on the Jewish Question, four texts are absolutely dominant in the nationalist discourse of that century: two from Germany and two from France. The German examples are Richard Wagner’s Jewry in Music (1850) and Wilhelm Marr’s The Victory of Judaism over Germandom (1879; summary and commentary here). Wagner’s piece is interesting for a number of reasons, not least his sardonic assessment of liberalism. When Europeans found themselves caught up in a drive to ‘emancipate’ the Jews, it wasn’t as a result of careful analysis of the possible positive or negative consequences of such an action. Rather, those involved were merely “champions of abstract principle.” Liberalism, argues Wagner, is “not a very lucid mental sport.” Liberalism relies on emotion and feelings, rather than rationality and facts. Europeans had been duped into fighting for the ‘freedom’ of a people “without knowledge of that people itself, nay, with a dislike of any genuine contact with it. … Our eagerness to level up the rights of Jews was far more stimulated by a general idea, than by any real sympathy.” Of course, the same argument might be made today in relation to the ‘refugee’ craze. Liberals are merely in love with the idea of helping migrants, rather than this being something they are genuinely emotional about. Liberalism, as Wagner rightly perceived, is the political expression of selfish emotionality. Aside from his musings on Liberalism, Wagner’s comments on Jews in culture are so profound and extensive that they cannot be adequately be covered here. It simply remains to be said that Jewry in Music is an essential text, worthy of careful study.

Marr’s book is important, but remains one of my own least favorites. The reasons for this lie in both its journalistic rather than scholarly approach, and in its pessimistic and almost claustrophobic tone. For Marr, a journalist, the Jewish Question is barely worth consideration because Judaism has already enjoyed total victory over Europe. He writes in sharp staccato sentences, and each is ripe with despair: “There is no stopping them. … A sudden reversal of this process is fundamentally impossible. … The Jewish spirit and Jewish consciousness have overpowered the world.” Beneath this thick blanket of suffocating pessimism, there are nevertheless occasional gems of insight and analysis from Marr. Of particular interest are his comments that the modern, Christian state would be no help to the nationalist cause because a synchronicity of values had taken place between the Jews and the state. Chief in this regard was the shared assumption and value that nationality would be reduced to a matter of paperwork — the idea that belonging to a nation merely meant that you were in a sense ‘contracted’ to a particular state. Marr is also worth reading because of his focus on the inertia of the masses in the face of rising Jewish influence. For example, he finds it remarkable that Jews have been able to conquer entire national systems without violent revolution but instead “through the compliance of the people.”

Marr’s book is important, but remains one of my own least favorites. The reasons for this lie in both its journalistic rather than scholarly approach, and in its pessimistic and almost claustrophobic tone. For Marr, a journalist, the Jewish Question is barely worth consideration because Judaism has already enjoyed total victory over Europe. He writes in sharp staccato sentences, and each is ripe with despair: “There is no stopping them. … A sudden reversal of this process is fundamentally impossible. … The Jewish spirit and Jewish consciousness have overpowered the world.” Beneath this thick blanket of suffocating pessimism, there are nevertheless occasional gems of insight and analysis from Marr. Of particular interest are his comments that the modern, Christian state would be no help to the nationalist cause because a synchronicity of values had taken place between the Jews and the state. Chief in this regard was the shared assumption and value that nationality would be reduced to a matter of paperwork — the idea that belonging to a nation merely meant that you were in a sense ‘contracted’ to a particular state. Marr is also worth reading because of his focus on the inertia of the masses in the face of rising Jewish influence. For example, he finds it remarkable that Jews have been able to conquer entire national systems without violent revolution but instead “through the compliance of the people.”

Marr’s text had an impact beyond Germany, and was certainly widely discussed throughout Europe. However, its pessimistic and apocalyptic tone was not entirely original. In 1845 Alphonse Toussenel, a French publicist and amateur ornithologist, wrote Les Juifs, rois de l’epoque (The Jews: Kings of the Epoch). Like Marr, Toussenel saw his nation engulfed by “terrible stagnation” and its people consumed by “a general inertia and torpor of the spirit.” France, in his opinion, was in the midst of a critical period in its history, a period in which parliament was powerless and the law had been reduced to the level of financial transaction. Wielding influence over this dazed nation was a “feudal clique,” the Jews. Much like Marr’s text, I found the negativity of Toussenel’s work to be overpowering, and certainly it is inferior to the best French work on the Jewish Question of the nineteenth century: Edouard-Adolphe Drumont’s La France Juive (Jewish France), published in 1886.

In Jewish France, Drumont (1844–1917), a journalist and leader of the political anti-Semitic movement in France, employed his considerable investigative talent to present one of the most comprehensive and factual accounts of Jewish influence produced in the nineteenth century. The book went through one hundred printings in a single year, turning Drumont into one of the best known public figures in France. One of the texts great strengths was that it didn’t rely on a single approach or viewpoint. It wasn’t just academic or journalistic, and it didn’t focus purely on politics or culture. The work embraced references from sources as varied as Catholics and socialists, while also including substantial elements of history, economic statistics, race science, and social criticism. Perhaps its greatest quality, however, is its break from the pessimism of Toussenel and Marr. Drumont writes of “considerable obstacles,” but asserts that “they are not insurmountable.” In many respects the work is a bridge between older texts, and those of the twentieth century and later.

It is to modern works on the Jewish Question that we now turn our attention.

Comments are closed.