Sartre’s “Anti-Semite and Jew”: A Critique [Part One]

“That book is a declaration of war against anti-Semites, nothing more.”

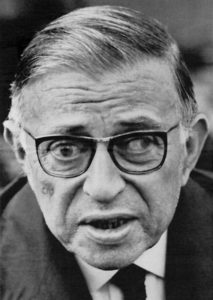

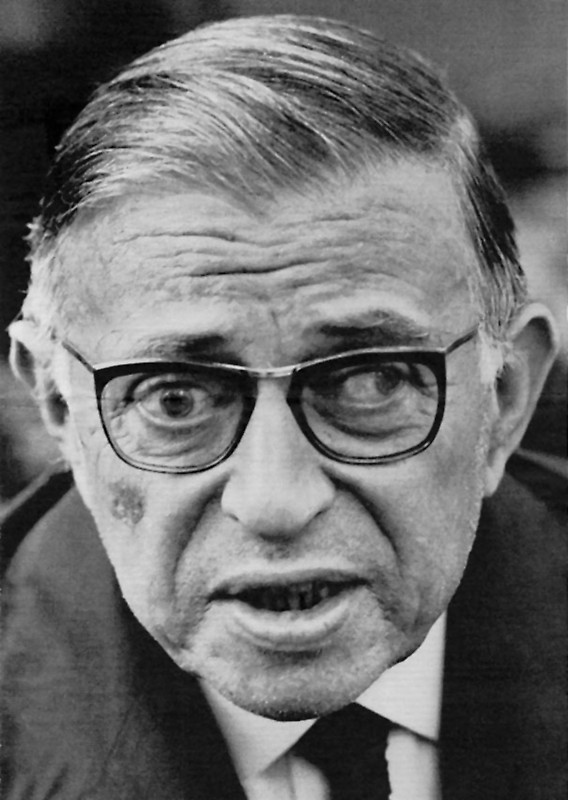

Jean-Paul Sartre, 1980.

A little over a decade ago I decided to research the Jewish Question in earnest. The precise chain of events leading to this decision was complex, but the main engine driving it was sheer intellectual curiosity. Here was a subject at once profound and deeply entwined with European history, and yet also obscure and apparently also half-sunk in a quagmire of shame. As a young developing scholar in the Arts, I felt the Jewish clash with Europeans had it all — economic aspects, religious factors, the opinions of philosophical giants, the dictates of kings and the risings of peasants. Here was history in raw, perpetually political form. As a result, I found myself haunting college and public libraries, slowly absorbing the topic’s mainstream texts, along with the not so mainstream, until one day I came across a small, unassuming volume just barely visible between two much larger books.

The name of the author brought about a spark of recognition, but it was the title that made me reach for it. There was something about Anti-Semite and Jew (1946) that suggested a personal approach to the subject that I felt had been hitherto lacking in the works I’d consulted. I took Sartre’s slim monograph to a nearby table where I devoted an afternoon to some but not all of its contents. I couldn’t finish it. Materially sparse and logically recondite, the book disappointed all initial hopes. I returned it to the shelves, and for the next ten years never felt the need to consult Sartre’s contribution to the discussion of anti-Semitism.

Until now. Prompted by a public radio discussion on Sartre (mainly focussing on his childhood and private life), around three months ago I decided to return to the Frenchman’s ideas on anti-Semitism — not because of any value inherent in the ideas themselves, but because of what a thorough critical treatment of them might tell us about Sartre and about philo-Semitic apologetics in general. During that time, I examined the text in full, making notes as I progressed. These notes eventually formed the following essay, which is, as far as I am aware, the first time that an ‘anti-Semite’ has replied to Sartre’s work.

The Significance of Anti-Semite and Jew

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) was a French philosopher, writer, political activist, and literary critic. In 1964, Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize for his literary work but refused it on the grounds it was a cultural symbol with which he did not wish to be associated. He is perhaps best known as one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism, an area of philosophy which contends that Man is a self-creating being who is not initially endowed with a character and goals but must choose them by acts of pure decision — existential ‘leaps.’ Sartre was born into a bourgeois Parisian family of comfortable means but would go on to be generally regarded as one of the most important Marxist philosophers of the 20th century. His father died when he was 15 months old, something which I believe profoundly affected the philosopher, consciously or not, throughout his life.

Sartre may be usefully characterized as someone in several respects at war with his roots, a fact demonstrated in stories (almost certainly apocryphal) from his autobiography and related to friends. Among them, for example, is an account of Sartre throwing his family tree into a waste basket.[1] Much of his future intellectual work could be seen as a rebellion against his own deeply bourgeois roots and perhaps even a form of self-loathing or an attempt to escape the Self. Never growing more than five feet tall, and painfully aware from a young age of his physical unattractiveness, Sartre invested a great deal of time on philosophical speculations on ugliness. Importantly, he viewed his ugliness as a form of social marginalization. It is particularly interesting that in these discussions he linked ugliness to other forms of perceived social marginalization, and even more interesting that he sometimes used the formulation “Aryan/Jew, handsome/ugly.”[2] Stuart Charme remarks:

To be labelled with one of the negatively valued of these “unrealizables” (Jewish, ugly, vulgar) is immediately to be exiled to social marginality. Yet the society of the marginalized also offers a kind of freedom not available to those preserving conventional values. For Sartre, to internalize ugliness as an important part of his identity is just one of his many attempts to ally himself with the negative Other of bourgeois society. Ugliness would be a visa stamped on his face that might gain him admission to the ranks of the authentically marginal and a way out of the world of the marginally authentic.[3]

Sartre was thus a man actively seeking a way out of a community and social structure he viewed as having rejected him, as well as seeking alliances with those he felt were already on the periphery or in opposition to the same community and social structure he felt antipathy towards. Charme suggests that Sartre’s ugliness, as well as his

discomfort and embarrassment regarding his own bourgeois background led him to idealise marginal groups and others who are seen as outside the normative model of selfhood. He identified part of his own self, moreover, with the situation of such classic outsiders as Jews, women, homosexuals, Blacks, and other groups. But it was the Jews in particular who represented the clearest embodiment of otherness for Sartre. …Throughout his life Sartre was intrigued by the situation of the Jews. …To a certain extent, his ideas about Jews reflected his own mythology of the Other. They reveal more about Sartre’s attitude toward his own background than they do about his knowledge of Jews and Judaism.[4]

Sartre, in later life, would come to acknowledge this psychological entanglement of identities, writing “while I believed that I was describing the Jew in Anti-Semite and Jew, I was describing myself.”[5] I suggest that psychological mechanisms evident here in Sartre, alongside his ostensibly impartial literary/philosophical defense of the Jews, provide a useful counter-argument to the idea of ‘pathological altruism’ in White actions on behalf of minorities, at least among the more radical and dedicated of such socio-political actors. Essentially, in what may be described as self-deception, or a variation on the Marxist theme of ‘false consciousness,’ Sartre and those like him feel abandoned or targeted by their surrounding culture, and then begin to see themselves as having interests (often highly abstract rather than material) different from that culture. They then construct ideological frameworks in which they advance these wholly adopted interests but do so in such a way as to deceive themselves that these ideologies are moral-intellectual crusades rather than what they truly are — an elaborate flight from the weakness of the Self. It’s quite possible that there is a similar dynamic going on with many sexual non-conformists (LGBTQ…) who become hostile to traditional institutions and values because they have low social status within the traditional framework and then develop theories which condemn traditional values and institutions and in which their own particular sexual orientation is seen as morally above reproach or even superior to heterosexuality. Of course, a similar dynamic is likely in the case of Jews become hostile to the traditional social order because they see it as anti-Jewish.

What results is not necessarily a pattern of self-hatred, but certainly an act of aggression: a revenge of the weak or, in Nietzsche’s formulation, a revolt of the slave. It is further argued here that the gravitation of such individuals towards Jews (and Sartre was not alone in this) and the growing tide of non-White immigrants is not so much an act of genuine altruism and brotherhood, but also an implicit, if often unconsciousness, demonstration of the understanding that these groups are oppositional forces arrayed against Western culture and its people, and therefore appropriate allies. Importantly then, Sartre didn’t need to demonstrate a genuine interest in religious Judaism, but rather a genuine interest, indeed obsession, with the Jew as agent of cultural critique, as opponent of the West, and as template for social revenge. Again, the contention here is that Sartre and his work on Jews is a classic demonstration of such a mechanism in action.

Sartre’s psychology had a highly significant bearing on the development of the ideas advanced in Anti-Semite and Jew. In some respects Sartre’s life and interests mirror very closely that of David Dellinger (the radical member of the mostly Jewish ‘Chicago Seven’ ) and Ted Allen (a pioneer in ‘Whiteness studies’). These are individuals of European ancestry who actively sought out deep relationships with a Jewish milieu and adopted forms of Jewish thinking hostile to Europe and its peoples — an extreme form of philo-Semitism which manifests in efforts not only to ingratiate oneself with Jews by attacking one’s own ethnic group, but to undertake efforts to ‘become Jewish’ in cultural or psychological forms (with or without religious conversion). Confronted not only with Anti-Semite and Jew, but with significant elements of the philosopher’s life and work, it is particularly interesting that Sartre scholar Michel Contat has asked: “Is Sartre a super-Jew, an honorary Jew?”[6] Steven Schwarzschild concurs somewhat, writing that “the phenomenon of the Jew is located even closer to the center of Sartre’s works and life than is popularly realised. … In the end, Sartre regarded himself, with no little justification, if not as a Jew then as a Judaicist.”[7] John Gerassi, a friend and contemporary of Sartre’s, recalled that at the end of his life the philosopher was “searching for his ‘Jewish roots.’”[8]

In terms of his personal life, Louis Menand comments that Sartre had a “sadistic attitude to sex” and exercised this with a series of Jewish lovers, among them a 16 year old girl named Bianca Bienenfeld whom he ‘shared’ with his part-time bisexual girlfriend and later influential feminist, Simone de Beauvoir. Sartre’s adopted daughter Arlette was Jewish, and in his autobiography, Les Mots, he refers to his father as Moses.[9] While studying at the Sorbonne, and for some time afterwards, Sartre embedded himself in a predominantly Jewish circle of friends, among them the Jewish anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss and the Jewish anarchist philosopher Simone Weil.

In terms of culture, he had a near obsession with the Jewishness of Freud which resulted in his writing a play on that theme, The Freud Scenario. He was strongly attracted to psychoanalysis, which he first encountered as a lycée student in the 1920s, and remained deeply fascinated by it until the 1970s.[10] Charme notes that Sartre believed that “confronting the reality of bodily functions is a way of piercing bourgeois civility…Like Freud, Sartre felt he had an obligation to recognize and publicize the less civilised and less tasteful side of human existence.”[11] Some of Sartre’s work is so laden with scatalogical references and preoccupations that his ‘existentialism’ has been referred to by some critics as ‘excrementalism.’[12] In keeping with the ideas advanced above regarding Sartre’s ‘adoption’ of Jews as a method of social revenge, Sartre, in his own words, saw Freud as a “profoundly aggressive” figure acting against his surrounding culture in order to avenge “the anti-Semitism from which his father suffered.”[13] When Sartre adds that Freud was “a child who felt things very deeply and probably immediately,” one is once again confronted with the question of whether Sartre is again describing himself via Jewish proxies; immersing himself in the imagined Jewish experience, adopting, ventriloquising, and assisting Jews as a form of vengeful self-expression.

Sartre also advanced an atheistic concept of the Jews as “Chosen People,” once writing that “there is a sincerity, a youth, a warmth in the manifestations of friendship of a Jew that one will rarely find in a Christian, hardened as the latter is by tradition and ceremony.”[14] Setting aside Sartre’s ignorance of Jewish tradition and ceremony and its impact on Jewish-Christian relations over centuries (which will be explored later), this is an irrational and remarkable demonstration of philo-Semitism which more than evinces its own form of prejudice. In the context of even this brief biographical sketch, a purportedly impartial and clinical book published by such an individual on the themes of anti-Semitism and the nature of Jewishness should obviously be treated with great caution.

Perhaps the most lasting significance of Anti-Semite and Jew is that it remains a classic work of philo-Semitism which continues to prove useful to the broader system of Jewish apologetics. Robert Misrahi notes that when the text was published in 1946 “its impact was immediate.”[15] Misrahi writes of an “emotional response” among Jews who were “deeply affected” that such a high-profile figure would write on their behalf, and were “full of admiration for the writer.” On June 3 1947, France’s largest Jewish organization, Alliance Israelite Universelle, organized a large-scale event for Sartre to give a lecture and promote the book. “Posters advertising the lecture were sent to all the synagogues in Paris, Neuilly, Vincennes, La Verenne.”[16] Sartre had made it clear he wanted to “be on their side,”[17] and the book, in Misrahi’s opinion, had a “positive practical and social impact.” Part of its practical impact owed to its practical proposals — one of the key recommendations of the text was that Jews should organized more effectively into defense bodies like the Anti-Defamation League. Jews received the publication of the book not only as

a powerful affirmation of sympathy, but even more importantly, it was an effective weapon against anti-Semitism…So much so, in fact, that after the book’s publication it became much more difficult for anti-Semitism to be publicly expressed. Sartre’s prestige, authority, talent and philosophy had succeeded in making any anti-Semitic approach or thought an outrage.[18]

The text retains a high level of academic and social respect, somewhat boosted by Jewish scholars and the Leftist tilt of modern academia, with Joseph Sungolowsky writing in Yale French Studies that Anti-Semite and Jew “remains one of the most lucid and penetrating analyses of the Jewish problem.…It is not exaggerated to consider Sartre’s book a classic.”[19] Michael Walzer posits the text as “a powerfully coherent argument.”[20] Marxist historian Enzo Traverso, meanwhile, has pointed to it as a “classic diagnosis” of anti-Semitism.[21]

It is the phrasing of Traverso’s assessment that points to the heart of the significance of Anti-Semite and Jew, because Sartre’s text represented one of the earliest and most prestigious arguments in favor of the idea that anti-Semitism was a form of emotional pathology, or an almost medical deformity of the personality. Writing in 1949, Jewish academic Julian Aronson, evidently eager to adopt and extend Sartre’s terminology, commented that Sartre’s “principle contribution to the literature of anti-Semitism is his stress on the personality factors behind the malady.”[22] Traverso comments that Sartre ‘diagnosed’ anti-Semitism as “an emotional syndrome.”[23] Walzer writes that Sartre’s “portrait of the anti-Semite is commonly and rightly taken to be the strongest part of the book.”[24]

When Misrahi praised the “originality” of Anti-Semite and Jew, it was primarily because of the novelty of pathologizing the anti-Semite that he was referring.[25] The importance of this dubious innovation can’t be stressed enough. Prior to the early twentieth century, anti-Semitism had, in its worst social and cultural representations, been portrayed as a form of bullying. Certainly, by the nineteenth century the term ‘Jew-baiting’ was employed as a synonym for the ‘bullying of Jews’ when one wished to disparage anti-Jewish agitations, and the term implied the indecorous exertion of strength by the strong or the masses, over a putatively weak Jewish minority. It should be stressed here that anti-Jewish agitations were not necessarily viewed as ill-founded or even unjust in such critiques, but rather, in the British parlance, that it was ‘bad form’ to be a ‘Jew-baiter’ and to call for harsh or discriminatory actions against Jews. There was a broad, diffuse, consensus in European culture that Jews were a problematic people, but that this was a problem that was best allowed to simmer rather than bubble over. Anti-Semitism, to use the modern terminology, was therefore for the most part critiqued for its method of expression rather than for the basis of its expression.

The changing of this position occurred slowly at first, helped along by psychoanalysis and the further intrusion of Jews into European cultural discourse, but also, I believe, in the coining by Wilhelm Marr of the term ‘anti-Semitism.’ Although created by a self-styled German ‘anti-Semite’ as a label for his ‘anti-Semitic’ movement, the term lent itself more readily than ‘Jew-baiting’ to scientific and even medical pretensions, and these were eventually exploited and inverted—to the great gain of Jewish apologists. Indeed, the term was almost immediately adopted into English usage in the 1880s as a pejorative, and its most high-profile early usage in the English language was by the Chief Rabbi of the British Empire.[26] Since that date ‘anti-Semite’ has remained predominantly a slur, or at the very least a term used almost exclusively for Jewish apologetic responses to anti-Jewish critique.

Sartre’s preoccupation with Jewishness and psychoanalysis, coupled with his Marxist/existentialist philosophy helped pave the way to a critique of anti-Semitism laden with the language of psychopathology. This was something of an innovation, especially from a non-Jewish European, and it should come as no surprise that Sartre’s work on anti-Semitism was eagerly followed by the Frankfurt School, and was probably influential in shaping their work to some degree. Omar Conrad notes “a close affinity between the critical theorists’ depiction of the authoritarian personality and Jean-Paul Sartre’s portrait of the anti-Semite,” adding that there are “many important points of congruence between Sartre and Adorno et al.”[27] Michael Walzer adds “Anti-Semite and Jew, in its best passages, stands with Theodor Adorno’s study of the Authoritarian Personality.”[28] Like the Frankfurt School, Sartre claimed to be highly skeptical in regards to the question of biological inheritance.[29] Also like the Frankfurt School, Sartre relied heavily on ‘character sketches’ or illustrations of ‘personalities’ as a means of creating and advancing his theories and arguments regarding anti-Semitism (this methodology will be critiqued later). According to John Gerassi, Herbert Marcuse had “carefully read all of Sartre’s works.”[30] Theodor Adorno, meanwhile, in a footnote to The Authoritarian Personality (1950), refers to Anti-Semite and Jew as “Sartre’s brilliant paper,” and describes similarities between Sartre’s book and his own “empirical observations” as “remarkable.”[31]

What we see here is the interaction of early efforts to design a theoretical framework with which to pathologize not anti-Semitism as such, but the anti-Semite. In the aftermath of the National Socialist government in Germany, prior forms of Jewish apologetics were seen as having failed or were at least regarded as insufficient to ensure Jewish security. Sartre’s innovations, a blend of Marx and Freud, developed alongside those of the Frankfurt School in an effort to move Jewish apologetics into a more aggressive stance — to directly assault the reputation and personality of the anti-Semite and make him a social pariah and portray his opinions as nothing more than a manifestation of underlying psychopathology. It was therefore not for nothing that the Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas praised Sartre for giving Jews “a new weapon” with which to combat anti-Semitism.[32] The aggressive descriptive language used by many of these commentators was of course no coincidence, since this was essentially the recruitment of ideas in the service of ethnic warfare rather than objective scholarly enquiry. Sartre himself would state that his book was “nothing more” than a “declaration of war against anti-Semites.”[33]

And on this note, we turn our attention to the contents of the text.

[1] A. Cohen-Salal, Sartre: A Life (New York: Heinemann, 1988), p.41

[2] S. Hammerschlag, The Figural Jew: Politics and Identity in Postwar French Thought (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2010), p.88.

[3] S. Charme, Vulgarity and Authenticity: Dimensions of Otherness in the World of Jean-Paul Sartre (Amhert: University of a Massachusetts Press, 1991), p.30.

[4] Ibid, p. 106.

[5] Ibid, p. 105.

[6] M. Contat, ‘The Intellectual as Jew: Sartre Against McCarthyism: An Unfinished Play,’ October, Vol. 87 (1999), pp.47-62 (p.47).

[7] S. Schwarzschild, ‘J.-P. Sartre as Jew,’ Modern Judaism, Vol.3, No.1 (1983), pp.39-73, (p.39).

[8] J. Gerassi, Jean-Paul Sartre: Hated Conscience of his Century, Volume 1: Protestant or Protester? (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1989), p.22.

[9] C. Howells, Sartre: The Necessity of Freedom (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1988), p.188.

[10] D. Fisher, ‘Jews, Patients, and Father’s in Sartre’s ‘Freud Scenario’,’ Sartre Studies International, Vol. 2, No.2 (1996), pp.1-26 (p.1).

[11] Ibid, p.24.

[12] Ibid, p.23.

[13] Ibid, p.6.

[14] Quoted in R. Misrahi, ‘Sartre and the Jews: A Felicitous Misunderstanding,’ October, Vol. 87 (1999), pp.63-72, (p.64).

[15] R. Misrahi, ‘Sartre and the Jews: A Felicitous Misunderstanding,’ October, Vol. 87 (1999), pp.63-72, (p.63).

[16] P. Birnbaum, ‘Sorry Afterthoughts on Anti-Semite and Jew,’ October, Vol.87 (1999), pp.89-106, (p.89).

[17] R. Misrahi, ‘Sartre and the Jews: A Felicitous Misunderstanding,’ October, Vol. 87 (1999), pp.63-72, (p.64).

[18] Ibid, p.64 & 67.

[19] R. Sungolowsky, ‘Criticism of Anti-Semite and Jew,’ Yale French Studies, No. 30, (1963), pp.68-72, (pp.71-2).

[20] M. Walzer, ‘Preface,’ in Jean-Paul Sartre, Anti-Semite and Jew (New York: Schocken Books, 1995), p.vi.

[21] E. Traverso, ‘The Blindness of the Intellectuals: Historicizing Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew,’ in Understanding the Nazi Genocide: Marxism After Auschwitz (), p.31.

[22] J. Aronson, ‘Sartre on Anti-Semitism,’ Phylon, Vol. 10, No.3 (1949), pp.231-232 (p.232).

[23] Traverso, ‘The Blindness of the Intellectuals: Historicizing Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew,’ p.31.

[24] Walzer, ‘Preface,’ in Jean-Paul Sartre, Anti-Semite and Jew, p.viii-ix.

[25] Misrahi, ‘Sartre and the Jews: A Felicitous Misunderstanding,’ p.63.

[26] For the best available account of the early career of the term ‘anti-Semitism’ in English see D. Glover, Literature, Immigration, and Diaspora in Fin-de-Siècle England: A Cultural History of the 1905 Aliens Act (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 80-6.

[27] O. Conrad, ‘The Social Psychology of Anti-Semitism,’ Mid-American Review of Sociology, Vol. 16, No. 2 (Critical Theory and the Frankfurt School) 1992, pp.37-56, (p.37).

[28] Walzer, ‘Preface,’ in Jean-Paul Sartre, Anti-Semite and Jew, p.vii.

[29] Conrad, ‘The Social Psychology of Anti-Semitism,’ p.40.

[30] Gerassi, Jean-Paul Sartre: Hated Conscience of his Century, Volume 1: Protestant or Protester?, p.7.

[31] Conrad, ‘The Social Psychology of Anti-Semitism,’ p.44.

[32] Birnbaum, ‘Sorry Afterthoughts on Anti-Semite and Jew,’ p.92.

[33] Jean-Paul Sartre & Benny Levy, Hope Now: The 1980 Interviews (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1996), p.101.

Comments are closed.