Sartre’s “Anti-Semite and Jew”: A Critique [Part One]

“That book is a declaration of war against anti-Semites, nothing more.”

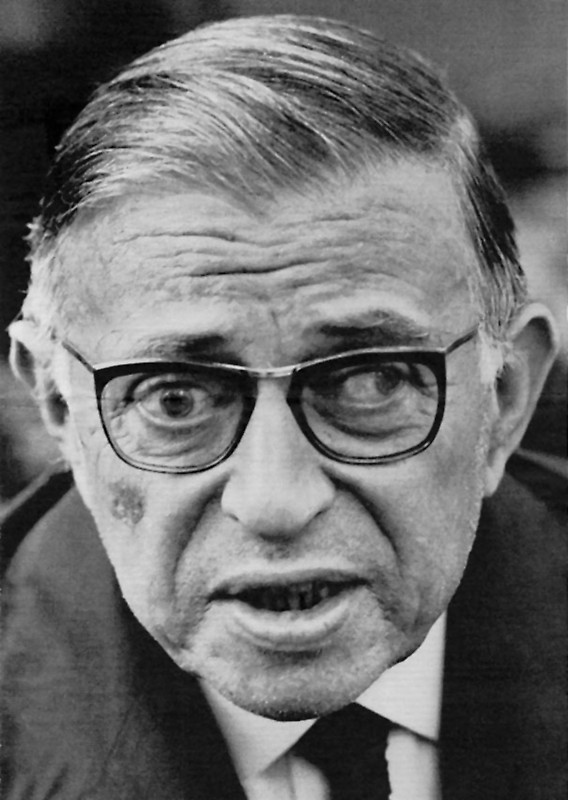

Jean-Paul Sartre, 1980.

A little over a decade ago I decided to research the Jewish Question in earnest. The precise chain of events leading to this decision was complex, but the main engine driving it was sheer intellectual curiosity. Here was a subject at once profound and deeply entwined with European history, and yet also obscure and apparently also half-sunk in a quagmire of shame. As a young developing scholar in the Arts, I felt the Jewish clash with Europeans had it all — economic aspects, religious factors, the opinions of philosophical giants, the dictates of kings and the risings of peasants. Here was history in raw, perpetually political form. As a result, I found myself haunting college and public libraries, slowly absorbing the topic’s mainstream texts, along with the not so mainstream, until one day I came across a small, unassuming volume just barely visible between two much larger books.

The name of the author brought about a spark of recognition, but it was the title that made me reach for it. There was something about Anti-Semite and Jew (1946) that suggested a personal approach to the subject that I felt had been hitherto lacking in the works I’d consulted. I took Sartre’s slim monograph to a nearby table where I devoted an afternoon to some but not all of its contents. I couldn’t finish it. Materially sparse and logically recondite, the book disappointed all initial hopes. I returned it to the shelves, and for the next ten years never felt the need to consult Sartre’s contribution to the discussion of anti-Semitism.

Until now. Prompted by a public radio discussion on Sartre (mainly focussing on his childhood and private life), around three months ago I decided to return to the Frenchman’s ideas on anti-Semitism — not because of any value inherent in the ideas themselves, but because of what a thorough critical treatment of them might tell us about Sartre and about philo-Semitic apologetics in general. During that time, I examined the text in full, making notes as I progressed. These notes eventually formed the following essay, which is, as far as I am aware, the first time that an ‘anti-Semite’ has replied to Sartre’s work.

The Significance of Anti-Semite and Jew

Jean-Paul Sartre (1905–1980) was a French philosopher, writer, political activist, and literary critic. In 1964, Sartre was awarded the Nobel Prize for his literary work but refused it on the grounds it was a cultural symbol with which he did not wish to be associated. He is perhaps best known as one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism, an area of philosophy which contends that Man is a self-creating being who is not initially endowed with a character and goals but must choose them by acts of pure decision — existential ‘leaps.’ Sartre was born into a bourgeois Parisian family of comfortable means but would go on to be generally regarded as one of the most important Marxist philosophers of the 20th century. His father died when he was 15 months old, something which I believe profoundly affected the philosopher, consciously or not, throughout his life.

Sartre may be usefully characterized as someone in several respects at war with his roots, a fact demonstrated in stories (almost certainly apocryphal) from his autobiography and related to friends. Among them, for example, is an account of Sartre throwing his family tree into a waste basket.[1] Much of his future intellectual work could be seen as a rebellion against his own deeply bourgeois roots and perhaps even a form of self-loathing or an attempt to escape the Self. Never growing more than five feet tall, and painfully aware from a young age of his physical unattractiveness, Sartre invested a great deal of time on philosophical speculations on ugliness. Importantly, he viewed his ugliness as a form of social marginalization. It is particularly interesting that in these discussions he linked ugliness to other forms of perceived social marginalization, and even more interesting that he sometimes used the formulation “Aryan/Jew, handsome/ugly.”[2] Read more