On “Leftist Anti-Semitism”: Past and Present

Leftist Critic of the Jews: William Cobbett (1763-1835)

–

If I had time, I would make an actual survey of one whole county, and find out how many of the old gentry have lost their estates, and have been supplanted by the Jews, since Pitt began his reign.

William Cobbett, Rural Rides (1826)

I can’t remember a time when the refrain “left-wing anti-Semitism” was more in vogue and yet so woefully misused. A quick Google search for the phrase returns more than four million results, including 65,000 results in which discussion of alleged leftist anti-Semitism forms a substantial element of a book. This curious but prolific fashion has accelerated remarkably in the last five years, with the publication, in relatively quick succession, of a number of texts posturing as ‘definitive’ treatments of the subject. The most notable of these are Stephen Norwood’s Antisemitism and the American Far Left (2013), Philip Mendes’s Jews and the Left: The Rise and Fall of a Political Alliance (2014), William Brustein’s The Socialism of Fools? Leftist Origins of Modern Anti-Semitism (2015), Dave Rich’s The Left’s Jewish Problem: Jeremy Corbyn, Israel and Anti-Semitism, and most recently, David Hirsh’s Contemporary Left Antisemitism (2017). This is in addition to the now incessant media chatter about the international activities of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement, and the similarly unending coverage in the U.K. of anti-Israel attitudes in Jeremy Corbyn’s Labour Party. All of this is of course irritatingly supplemented by interested parties (e.g., Jonah Goldberg and his 2008 Liberal Fascism) and their foreign lackeys in the co-opted Right (e.g., Dinesh D’ Souza), who proffer nebulous and entirely self-serving narratives of ‘Leftist Fascism’ to those still ignorant enough to respond to propagandized trigger words with all the thoughtless obedience of a well-trained dog.

It really shouldn’t take much careful thought to come to the conclusion that this oft-claimed “leftist anti-Semitism” is a phantom of the Jewish imagination, transmuted into a politically useful meme and disseminated with shameless persistence via the mass media and the co-opted political establishment. The first step in dismissing this meme is to abandon propagandistic definitions of anti-Semitism, which these days categorize any negativity against Jews and their interests as irrational, pathological, and quasi-genocidal. What, then,is anti-Semitism? Anti-Semitism, if the term is to retain any use for us at all, can best be conceived as a framework of understandings or archetypal narratives concerning Jews (both individually and as a group) which enable reasonably accurate predictions or prejudgments of Jewish behavior, or which act to caution one against contact with Jews. One might well call it a ‘prejudice,’ but like all prejudices it has an inherent value and usefulness which cannot be simply waved away with abstract ‘moral’ objections. I argue that it is the content of this framework of understandings which should be sought in anything defined or self-defining as anti-Semitism. Helpfully, the fundamentals of anti-Semitism have remained largely unchanged for over 2,000 years and these features are straightforward and easily identified. For example, the second chapter of Kevin MacDonald’s Separation and Its Discontents: Toward an Evolutionary Theory of Anti-Semitism (2004) is devoted to the “Themes of Anti-Semitism.” In summary, those presented by MacDonald include the understandings that Jews are clannish and self-segregating, that Jews have a special relationship with money and a corresponding tendency to economic domination, that Jews possess a certain set of negative personality traits including a tendency to dissimulation, that Jews engage in the manipulation of surrounding cultures in order to pursue their own group interests, and finally that Jews are “less loyal” than those native to the host culture or nation.

These understandings are simply not present in the modern Left, not even in a cryptic or subtle form. What is present in the Left is a strident anti-Zionism based on a combination of genuine horror at the treatment of Palestinians by the Israeli government and military, and a dogmatic belief in cultural Marxist narratives of Western imperialism. Neither share an intellectual, cultural, or ideological lineage with the European anti-Semitic tradition. Attempts to describe the Left as ‘anti-Semitic’ are in fact based on the same tendentious logical suppositions as equally prolific notions of a “new anti-Semitism.” [There are more than two million hits in Google Books for this term]. The concept of anti-Semitism as an ever-changing or ‘mutating’ psychological virus is appealing to Jews, and almost exclusively promoted by them [e.g. see this piece by Guardian journalist Nick Cohen], for a number of reasons. The first and most obvious reason is that it shifts all blame away from Jews. The second is that it is conducive to a key aspect of Jewish self-deception — what Albert Lindemann called “the parallel instinct to view surrounding Gentile society as pervasively flawed, polluted, or sick.”[1]

The specific grievances which go into provoking anti-Semitism are striking in their persistence and uniformity. Kevin MacDonald notes that “the remarkable thing about anti-Semitism is that there is an overwhelming similarity in the complaints made about Jews in different places and over very long stretches of historical time.”[2] However, Jews have engaged in the self-deception that anti-Semitism is instead constantly evolving and mutating to catch up with them, and that this ‘disease’ is constantly threatening to reach pandemic proportions among the Gentiles. Jews avoid facing the necessity of changing their behavior by convincing themselves that no matter what steps they might take to change their behavior, the ‘anti-Semitic virus’ will adapt or mutate in order to target them.

The flexibility of such a theory of anti-Semitism obviously also makes it a useful tool to Jewish interests. Lacking definite structures and rhetorical boundaries, it can be deployed at will to encompass any behavior deemed undesirable by Jews. Thus, any act of negativity towards Jews becomes another example of the “new anti-Semitism.” Such flexibility also absolves Jews of the need to come to explain in concrete and consistent terms where, why, and how anti-Semitic feelings are aroused. The ‘authoritarian personality,’ economic failures, social marginalization, nationalism, personal jealousies, psychological pathologies, status anxiety, radical leftism — all these and more can be shamelessly produced in varying combinations as semi-credible explanations because anti-Semitism is by nature, according to Jewish theorizing and in contrast to all evidence, inherently fluid.

One of the most powerful, if not totally successful, efforts in this sphere of Jewish apologetics is the attempt by the organized Jewish community to conflate anti-Zionism, which presently manifests most strongly on the Left and among student groups, with the fictional concept of the “new anti-Semitism.” Indeed, the meme that anti-Zionism is essentially anti-Semitism is the linchpin of the concept of “leftist anti-Semitism.” Without the former rhetorical device, the latter appears weak, if not absurd, in light of the ‘special relationship’ between Jews and the Left from the mid-nineteenth century to the present. Hyperbole is both common and necessary to this propaganda effort. All criticism of Israel is portrayed as an effort to undermine and abolish the Jewish state, throwing Jews to a host of vaguely defined but allegedly ever-present genocidal predators. An excellent recent example is that of Jonathan Arkush, President of the Board of Deputies of British Jews, who stated just before he left office that Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn had “delegitimised the State of Israel by indulging the “prevalent discourse about Israel,” [“a discourse which denies the existence of their own land to the Jewish people”] and thus holds views that are “unquestionably anti-Semitic.” The phrasing of Arkush’s comments is itself a stellar example of Jewish socio-political myopia — with almost every Western nation officially supporting Israel, or unofficially pursuing a policy of appeasement, it is dissent to this overwhelming norm that Arkush dares describe as the “prevalent discourse.”

Jewish blindness to their privileges, genuine or feigned, is of course one major cause for the undeniable friction between Jews and the modern Left. It was perhaps inevitable that foolish but earnest egalitarians on the Left would come to the slow realization that their ‘comrades of the Jewish faith’ were in fact not only elitists, but an elite of a very special sort. The simultaneous preaching of open borders/common property and ‘the land of the Jewish people’ was always going to strike a discordant note among the wearers of sweaty Che Guevara t-shirts, especially when accompanied so very often by the cacophony of Israeli gunfire and the screams of bloodied Palestinian children. Mass migration, that well-crafted toxin coursing through the highways and rail lines of Europe, has proven just as difficult to manage. Great waves of human detritus wash upon Western shores, bringing raw and passionate grievances even from the frontiers of Israel. These are people whose eyes have seen behind the veil, and who sit only with great discomfort alongside the kin of the IDF in league with the Western political left—the only common ground being a shared desire to dispossess the hated White man.

For these reasons, the Left could well become a cold house for Jews without becoming authentically, systematically, or traditionally anti-Semitic. One might therefore expect Jews to regroup away from the radical left, occupying a political space best described as staunchly centrist — a centrism that leans left only to pursue multiculturalism and other destructive ‘egalitarian’ social policies, and leans right only in order to obtain elite protections and privileges [domestically for the Jewish community, internationally for Israel]. A centrism based, in that old familiar formula, on ‘what is best for Jews.’ A ‘centrism’ typified to varying degrees by the Jewish clique clustering around Quillette, and promoting similarly ‘centrist’ ideological vacuums like Jordan Peterson. A ‘Jewish centrism’ that disseminates the memes of ‘leftist anti-Semitism’ and ‘liberal fascism,’ which are then greedily consumed with gusto by Corporate Conservatism, Promised Land Christians, and Beer Patriots.

Faced with such a patchwork of fictions, we might ask whether or not a ‘leftist’ or ‘radical egalitarian’ anti-Semitism’ could ever exist and, if so, what it would look like. In this regard, we would have to delve deeper into history — into ideas which prefigure Marx and Engels and correspond more closely with a true, authentic, even quasi-ethnic or ‘national’ socialism. Here the example of William Cobbett is highly instructive.

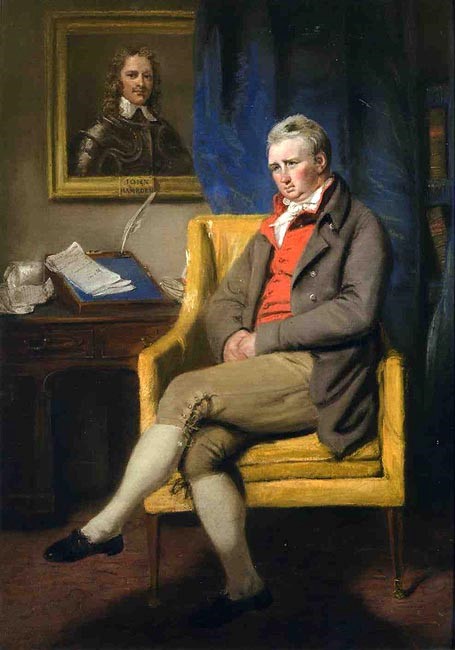

The name of William Cobbett (1763–1835) will not be very familiar to non-British readers. Within the United Kingdom, however, this radical agitator from two centuries ago retains a significant level of prominence and esteem. His career is a standard component of the national high school history curriculum. In his home county of Hampshire there remain schools and pubs named after him. One can take heritage walks to see where and how he lived. There is a William Cobbett Society. Volumes of books have been published describing him as a hero. His image hangs in Britain’s National Portrait Gallery.

The reasons for Cobbett’s fame are clear. A farmer’s son, he worked as a farm laborer, gardener, clerk, soldier, journalist, and politician. He is remembered mainly for his opposition to the Corn Laws, legislation imposed between 1815 and 1846 which essentially blocked cheap food imports from abroad, artificially maintaining high domestic food prices. Cobbett blamed Britain’s increasingly aloof and selfish aristocracy as well as its mercantilist culture, built on the development of debt finance, for the decline in the fortunes of the English working class as well as the starvation of the Irish. His Political Register newspaper is often credited with the invention of popular radical journalism, and was the main newspaper read by the working class. His bitter opposition to the British aristocracy led the government to consider arresting him for sedition in 1817 — rumors of which caused Cobbett to flee to the United States, where he remained until matters settled somewhat two years later. When he returned, he paved the way for the 1832 Reform Act, which expanded the British franchise and paved the way for the expansion of democracy within the British Isles. Cobbett is also credited with laying the groundwork for the Chartist movement, which would campaign for universal suffrage and draw the attention of Marx, Engels, and the developing socialist network.

And yet there are elements in the thought and activism of William Cobbett that suggest he is, to say the very least, an uneasy fit for the modern Left. Cobbett disdained internationalism and cosmopolitanism, once stating “I am not a citizen of the world.…It is quite enough for me to think about what is best for England, Scotland, and Ireland.” He was, if you will, a ‘national’ socialist. Clearly ethnocentric, Cobbett was disdainful of the religious humanitarians of his day. When the anti-slavery campaigner William Wilberforce backed the Corn Laws, Cobbett attacked him for endorsing the starvation of his own people while giving all his support to “the fat and lazy and laughing and singing negroes.”

Cobbett was also profoundly oppositional to Jews. He was simultaneously one of the greatest champions of Catholic political emancipation and one of the fiercest and most relentless opponents of Jewish political emancipation. The latter he rooted in the detachment of Jews from the masses, rejecting the idea that Jews should have a say in government unless someone could “produce a Jew who ever dug, or who ever made his own coat or his own shoes, or who did anything at all, except get all the money he could from the pockets of the people.”[3] Instead, argued Cobbett, Jews “did not merit any immunities, any privileges, any possessions in house, land, or water, any civil or political rights.…They should everywhere be deemed aliens and always at the absolute disposal of the sovereign power of the state, as completely as any inanimate substance.”[4] He frequently praised the expulsion of Jews from England under Edward I. Jewish academic activist Anthony Julius opines that “in the work of William Cobbett, Jew-hatred is everywhere.…To be a financier is to act the part of a Jew.”[5] Julius quotes Cobbett as having argued that Jews “damaged France and killed Poland,” and that Jews are a people “living in all the filthiness of usury and increase…extortioners by habit and almost by instinct.[6] Julius laments that Cobbett’s “anti-Semitism exercised a certain diffuse influence on radicals in the early nineteenth century, if only at the level of vocabulary.…Cobbett enjoyed an immense popularity during his lifetime, and has a substantial posthumous reputation.”[7] In 1830 he published Good Friday: or the Murder of Jesus Christ by the Jews, where he wrote:

[Jews are] everywhere are on the side of oppression, assisting tyranny in its fiscal extortions; and everywhere they are bitter foes of those popular rights and liberties.…It is amongst masses of debt and misery that they thrive, as birds and beast of prey get fat in times of pestilence.…This race appear always to have been instruments in the hands of tyrants for plundering their subjects; they were the farmers of the cruel taxes; they lent a support to despotism, which it could not otherwise obtain.

In Paper Against Gold (1812), Cobbett expressed the belief that the concepts of paper money and the national debt were basically Jewish “tricks and connivances,” endorsed by an aristocracy grown greedy and toothless. Initially a loyalist, Cobbett later came to the opinion that while the concept of aristocracy was not altogether bad or illegitimate, the British aristocracy had betrayed and exploited the people it was supposed to lead. That the aristocracy had given itself over to Jewish thought, through ties of blood and finance, was hinted most strongly in the Political Register of December 6 1817:

Let us, when they have the insolence to call us the ‘lower orders,’ prepare ourselves with useful knowledge, and let these insolent wretches marry amongst one another, ‘till, like the Jews, they have all one and the same face, one and the same pair of eyes, and one and the same nose. Let them, if they can, prevent their footmen from bettering their blood and from reinforcing the limbs of their rickety race; and let us prepare for the day of their overthrow. They have challenged us to the combat. They have declared war against us.

One of the most potent contemporary critics of Cobbett’s political trajectory was Thomas Carlyle, who most famously took aim at radical egalitarianism in his renowned history The French Revolution (1837), but also in his lesser appreciated essay ‘Chartism’ (1840). Having recently re-read ‘Chartism,’ which was rejected by countless contemporary publishers due to its radical authoritarianism, I was struck not so much by the disagreements between Cobbett and Carlyle (the former advocating an expansion of the franchise and the latter advocating a radical curtailment of it), but by their agreements, particularly on the failings of the British aristocracy. For example, both Cobbett and Carlyle posit the English peasant as an ideal type within a broader context of blood-and-soil nationalism. Both object to laissez-faire economic policies — Cobbett on the grounds they are a cover for corruption, Carlyle on the grounds they represent an abandonment of the aristocratic duty to ‘guide.’ Both viewed the Irish peasant as having been brutalized by a British aristocracy which had rejected its duty to lead out of avarice and laziness, and which could soon do the same to the English peasantry. [In Carlyle’s phrasing: “Has Ireland been governed and guided in a ‘wise and loving’ manner? A government and guidance of white European men which has issued in perennial hunger of potatoes…ought to drop a veil over its face and walk out of court under conduct of proper officers, saying no word; expecting now a surety sentence either to change or die.”] Both viewed the aristocratic principle as worthwhile but felt strongly that the existing elite had grown corrupt, as well as morally and biologically weak. The only real difference in thought was that Carlyle felt the answer lay in concentrating power in the hands of a “great man” or dictator who would spring from the genius of the ‘lower orders,’ while Cobbett believed that the entirety of the ‘lower orders’ would muster enough genius to steer the nation in a better direction. Carlyle writes:

Whatsoever Aristocracy is still a corporation of the Best, is safe from all peril, and the land it rules is a safe and blessed land. Whatsoever Aristocracy does not even attempt to be that, but only to wear the clothes of that, is not safe; neither is the land it rules safe! For this now is our sad lot, that we must find a real Aristocracy, that an apparent Aristocracy, how plausible soever, has become inadequate for us.…With the supreme triumph of Cash, a changed time has entered; there must a changed Aristocracy enter.

Although these men were essentially polar opposites within the context of mid-nineteenth century British politics, it is fascinating and extremely telling that both would now conform to modern definitions of “far-right” thought. This really is a stunning demonstration of the almost total revolution in values that has taken place, especially since the 1960s. For example, Jean-Yves Camus and Nicolas Lebourg, in Far-Right Politics in Europe (2017), define as “far-right” those ideas which

challenge the political system in place, both its institutions and its values. They feel that society is in a state of decay, which is exacerbated by the state: accordingly, they take on what they perceive to be a redemptive mission. They constitute a countersociety and portray themselves as an alternative elite. Their internal operations rest not on democratic rules but on the emergence of “true elites.” In their imaginary, they link history and society to archetypal figures […] and glorify irrational, nonmaterialistic values […]. And finally, they reject the geopolitical order as it exists [p.22].

James Grande, one of Cobbett’s biographers, remarks that the radical’s legacy was ultimately hindered when his “anti-Semitism grated against the increasingly internationalist outlook of the movement.”[8] It is both fitting and deeply ironic, from Cobbett’s point of view, that the most “internationalist” of the new radicals was the Jew Karl Marx.

Is the modern ‘Left’ anti-Semitic? No.

Was the ‘Left’ ever anti-Semitic? All complexities of valid terminology, I leave you only with food for thought in the form of the fascinating career of the great English radical, Mr William Cobbett.

[1] A. Lindemann, Esau’s Tears, p.13.

[2] K. MacDonald, SAID, p.38.

[3] A. Julius, Trials of the Diaspora, p.401.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] J. Grande, William Cobbett, Romanticism and the Enlightenment: Contexts and Legacy (Routledge, 2015), p.134.

Comments are closed.