Decline and Empire in Ancient Rome and the Modern West: A Review of David Engels’ Le Déclin, Part 2

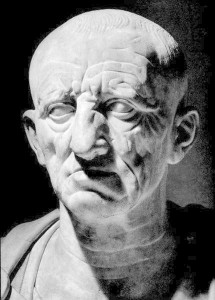

Cato the Elder

Roman Conservative & Imperial Responses

The Roman authorities, whether republican or imperial, did not passively accept these developments. Engels observes that “[f]rom the second century B.C., a large number of conservative politicians opposed with a marked traditionalism the Hellenization of the Roman elite and the Orientalization of the population” (142). This was embodied above all by Cato the Elder, who argued that Greek culture, which had become so rational, skeptical, and cosmopolitan, would mean the end of Rome:

Concerning those Greeks, son Marcus, I will speak to you more at length on the befitting occasion. I will show you the results of my own experience at Athens, and that, while it is a good plan to dip into their literature, it is not worth while to make a thorough acquaintance with it. They are a most iniquitous and intractable race, and you may take my word as the word of a prophet, when I tell you, that whenever that nation shall bestow its literature upon Rome it will mar everything. (Pliny, Natural History, 29.7)

In terms of immigration, as previously mentioned, Gaius Papius had on behalf of the people apparently sought to expel non-Italic foreigners from the city altogether. Augustus later limited the emancipation of slaves, “lest they should fill the city with a promiscuous rabble; also that they should not enroll large numbers as citizens, in order that there should be a marked difference between themselves and the subject nations” (Cassius Dio, 56.33).

The Roman leadership also sought to counter native demographic decline. As early as 131 B.C., the censor Quintus Metellus Macedonicus urged making marriage mandatory. Later, “in order to ensure the biological survival of the Roman elite, Augustus . . . decreed very unpopular laws” (83), including making marriage mandatory for men between 25 and 60 and making divorce more difficult. The emperor is supposed to have justified the measures as follows:

For surely it is not your delight in a solitary existence that leads you to live without wives, nor is there one of you who either eats alone or sleeps alone; no, what you want is to have full liberty for wantonness and licentiousness. … For you see for yourselves how much more numerous you are than the married men, when you ought by this time to have provided us with as many children besides, or rather with several times your number. How otherwise can families continue? How can the State be preserved, if we neither marry nor have children? . . . And yet it is neither right nor creditable that our race should cease, and the name of Romans be blotted out with us, and the city be given over to foreigners — Greeks or even barbarians. Do we not free our slaves chiefly for the express purpose of making out of them as many citizens as possible? And do we not give our allies a share in the government in order that our numbers may increase? And do you, then, who are Romans from the beginning and claim as your ancestors the famous Marcii, the Fabii, the Quintii, the Valerii, and the Julii, do you desire that your families and names alike shall perish with you? (Cassius Dio, 56.7–8)

Tellingly, Augustus himself however was married twice and had a reputation for licentiousness. His only biological child, Julia, was notorious for her licentiousness.

Augustus also sought to create a specifically Roman or Italic identity, despite the immigration, through efforts in education, propaganda, and architecture. Engels deems these a failure, however, as Roman culture gave way to a Greco-Mediterranean hodgepodge, notably in the sphere of religion, where are all sorts of strange foreign cults were indiscriminately imported.

Ultimately, while the Romans, like the Greeks, recognized the importance to biopolitics to the life of the republic in principle—for instance, the harsh eugenic measures that were justified both in the founding Twelve Tables of Roman law and later by Seneca—one is struck by the piecemeal and spiritless quality of these ultimately quite ineffective measures.

On the political level, the efforts of old-style republicans such as Cicero or Brutus to preserve the Republic proved completely inadequate. In the end, Augustus could establish an autocratic regime by purging the republican conspiracy which would have, he claimed, imposed “the tyranny of a faction” (197). The decline of the old Roman body of citizen-soldiers and of the aristocratic leadership, and the rise of a military-bureaucratic state lording over incoherent multicultural masses, made the rise of the autocratic Empire of the Caesars inevitable.

The West’s Imperial Turn?

Engels’ study of Roman history makes a powerful case for the connection between ethno-cultural vitality and civic politics. I personally would have liked to have known more about Roman ethno-cultural decline in the imperial era. Furthermore, Engels’ work overstates the strictly political parallel between the Roman Republic and the European Union: the former was a centralized military state, while the latter is a fractious confederacy analogous to the old Greek leagues of city-states (a comparison I would have liked to hear more about). As such, the EU seems quite unlikely to become such a genuine empire.

At the same time, one could argue such observations miss the point: Engels forecasts that the current liberal-democratic paradigm across the West is unsustainable in the face of the collapse of the indigenous population and the rise of multiethnic politics. A new form of post-democratic politics, already quite apparent in the EU, is inevitable, either in the form of liberal elites taking authoritarian measures to continue clinging to power (Germany, Great Britain, and Sweden are in many respects politically-correct police states) or in the form of a new wave of populist Caesarism (Hungary, Poland, perhaps America). Engels writes that, given the demographic trends, “‘Eurabia’ is a perfectly credible prediction” (78) and he has frequently told the media that Western Europe will be wracked by ethno-religious civil war within 20 to 30 years.

Engels argues for making the most of the inevitable rise of post-democratic politics, through an imperial Europe:

The dangers of a political domination by the “markets,” an authoritarian revolution, or an inter-ethnic war which loom could be avoided, or at least attenuated. Thus there would be the peaceful emergence of a moderate imperial Europe, far from the chauvinist narrowness of the anachronistic national State . . . Granted, this would not occur without an abandonment of the universalist ideal and without a return of the Europeans’ traditional values. (286)

This vision of a European Imperium, rather reminiscent of those of Francis Parker Yockey or Richard Spencer, will not be to everyone’s taste and would be disastrous so long as the actually anti-European open-borders fanatics who currently prevail in the EU remain in office.

Indeed, Engels faults EU elites for adopting an insipid, purely-geographical definition of European identity based on “universal values.” But, he points out that if those values are universal, how do they differentiate Europeans from other peoples? Crickets. Engels observes that “the popular masses … are in search of meaning and are tired of ‘political correctness’” (24). He laments that “to define an identity as complex as the European identity with sole reference to a geographical notion [as the EU does] bears witness of an appalling ideological vacuum and can only worsen the identitarian problem” (51).

Engels also faults European leaders for valuing peace above all and disowning the Continent’s history: “Can an entire continent build itself through the denial of its own turbulent history and therefore of the values which brought this history? One can doubt it. … Peace at any price and the condemnation of hostility must necessarily work to deconstruct identity” (201). Indeed, the Roman citizenry appear to have been united precisely by the presence of constant external threats and fell into division once their empire had given them lasting security. Whatever happens to the EU, in the long run, a pan-Western and pan-European bloc or power explicitly founded on ethno-cultural kinship and solidarity must and will prevail.

Engels’ study of Roman history should not lead us to a pessimistic fatalism, although one certainly walks away with an appreciation for history’s deep forces, often quite beyond the control of even of the most influential elites. True, both Rome and the West have seen the decline of their traditional culture and peoples as a result of civilization and world-empire. The situations of the modern West and ancient Rome are also very different however, in both good and bad ways. On the negative side, we are much, much more decadent and effeminate than even the worst of the Ancients, who had to live by the sweat of their brows. The affluent society, at least in its liberal version, has led to a general softness and intolerance to even mild discomfort, including a collapse in testosterone levels and sperm counts among Western men. This collapse in spiritedness (thumos) and manly virtue (virtus) is perhaps the most fundamental root cause of the problems. The peoples entering the West, often hailing from Sub-Saharan Africa and the furthest parts of Asia, are even more radically different than were those who immigrated to Rome.

At the same, we are living with an unprecedentedly elevated level of technology. This will present us with innumerable, difficult-to-predict threats and opportunities, including more widespread knowledge of biological science and untold potential for innovative population-reshaping biopolitics. In truth, the era of postwar democracy in the West was always a bit of a sham—those regimes always, in fact, being controlled by the relatively narrow oligarchic media and political elites. History has always been made by elites and states have always been dominated by elites, despite their democratic pretensions. If, as Engels and indeed Yuval Harari have said, the West is to be dominated by a post-democratic elite, let it be an enlightened elite, a spirited elite that understands biological realities and, most importantly, loves their people. Let our people become convinced that our biological preservation and upward cultivation is a profoundly moral undertaking, the great quest of this century.

Dr. Engels himself says that he is leaving Belgium because “I don’t want my two sons to grow up in that world. I don’t want them to think that what’s happening in Belgian cities is normal.” I understand that he is moving to Eastern Europe, where he will advise the Visegrád governments, which, like the Romans, have taken measures both to stop foreign immigration and to increase their birth rates. A word of exhortation: Your efforts can never be too vigorous!

Select Bibliography

Cicero (trans. P. G. Walsh), On Obligations (or On Duties), (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Seneca (trans. John Davie), Dialogues and Essays, including “Consolation to Helvia,” (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008).

Comments are closed.