Lothrop Stoddard’s “The French Revolution in San Domingo,” Part 2

There were complex combinations of oppositions according to race and class. On one hand, poor Whites and wealthy Whites saw a common interest in opposing the mulattos, some of whom were wealthy. From the standpoint of the poor Whites, the wealth of his perceived racial inferiors was particularly galling. In 1789, when the French Revolution had compromised the power of the Royal government, the wealthy Whites “anxious for poor white support, were not likely to embroil themselves to protect their race opponents [i.e., the mulattos]. By this time the local offices were becoming filled with poor whites, and to the will and pleasure of these new functionaries, the mulattoes were now delivered almost without reserve.”

On the other hand, the lower-class Whites (described by Stoddard as “mostly … ignorant men of narrow intelligence”) engaged in class war against wealthy Whites: They were “too short-sighted to realize the results of white disunion or too reckless to care about consequences.” They excluded upper-class Whites from voting by “violence and intimidation.”

Some observers have argued that the revolutionary ideals of moral universalism were an ingredient in the revolt of the non-Whites. Stoddard quotes approvingly an observer who attributes the fervor for revolt among slaves and mulattos to their being exposed to revolutionary rhetoric. “To discuss the ‘Rights of Man’ before such people—what is it but to teach them that power dwells with strength, and strength with numbers!” Stoddard expresses his own view that “there seems to be no doubt that the writings and speeches of the French radicals did have a considerable effect on the negroes.” And he provides the conclusion of contemporary investigations: “Both the existing evidence and the trend of events combine to show that the great negro uprising of August 1791 was but the natural action of the Revolution on highly flammable material.”

Nevertheless, as with all complex events, the causes remain in question. Stoddard suggests that the quarrels among the Whites were a major contributing factor. In any case, we do know that the Jacobin radicals in France refused to help their racial brethren in San Domingo—their refusals motivated by partisan politics couched in the high-flown rhetoric of moral universalism:

These appeals [from the French colonists in San Domingo and their relatives in France], coupled with the horrors contained in every report from the island, might well have moved hearts of stone; — but not the hearts of the Jacobin opposition. Time after time a grim tragi-comedy was enacted on the floor of the Assembly. Some fresh batch of reports and petitions on San Domingo would move moderate members to propose the sending of aid. Instantly the Jacobins would be upon their feet with a wealth of fine phrases, patriotic suspicions, and a whole armory of nullifying amendments and motions to adjourn; — the whole backed by gallery threats to the moderate proponents.

Besides the radicals, French business interests cared far more for retaining their markets than in racial solidarity: “The very commercial classes were now estranged from their former allies, since the French merchants had no desire to be ruined for the upholding of the color line. What appeared to colonists a vital principle seemed to Frenchmen a foolish prejudice, and the whites of San Domingo were more and more regarded as a stiff-necked generation in great part responsible for the woes which overwhelmed them.”

Whereas the radicals and the merchants cared nothing for racial cohesion, the colonists remained committed to racial solidarity, albeit with the class divisions mentioned above. Unlike the legislators and merchants in far off France, they could easily see how allying themselves with mulattos would affect them in the long run. They refused to make an alliance with the mulattos against the Blacks, fearing that they would eventually be out-voted by the mulattos. They also feared that lowered social barriers would eventually result in intermarriage and the mixing of blood. “The colonial whites grimly resolved to keep San Domingo a ‘white man’s country’ or to be buried in its ruins.” Despite the feelings of horror by the Whites of San Domingo, the mulattos were given the vote April 4, 1792 and a Jacobin army arrived to enforce the law.

Stoddard is openly contemptuous of the Jacobin radicals who refused to aid the Whites of San Domingo. “Of this opposition to the relief of San Domingo it is difficult to speak with moderation. For not even on grounds of fanaticism can the Jacobin policy be palliated.” Stoddard labels Léger-Félicité Sonthonax, one of the commissioners sent to enforce the law on mulatto political equality, “a sinister figure,” “a mere mouther of phrases, corrupt in both public and private life, his one real talent a certain sly ability to trim with the times which was to bring him safe through the storms of the Revolution.” “If such a man can be said to have real convictions, his ideas on colonial questions may be gathered from a signed article published in one of the ultra-radical sheets about a year before. ‘The ownership of land both at San Domingo and the other colonies … belongs in reality to the negroes. It is they who have earned it with the sweat of their brows, and only by usurpation do others now enjoy the fruits.’”

Sonthonax surrounded himself with mulattos and engaged in brutal military campaigns against Whites. Eventually he turned on the mulattos by freeing the Blacks under his control without authority from the French government. He wrote “it is with the real inhabitants of this country, the Africans, that we will yet save to France the possession of San Domingo.” Needless to say, freeing the Blacks was not warmly greeted the mulattos, many of whom owned slaves: “The mulattoes had everywhere greeted Sonthonax’s negrophil policy with ill-concealed rage; his emancipation proclamation had roused them to furious mutiny.”

Sonthonax is truly remarkable in his hostility toward the colonial Whites. One of his closest associates reportedly stated that “The white population must disappear from the colony. The day of vengeance is at hand. Many of these colonist princes must be exterminated.” Not surprisingly, there was a general exodus of Whites, mainly to the US.

Stoddard notes Sonthonax’s “lavish expenditure” and his opposing a White captain-general who had expressed an attitude of superiority to the mulattos. Stoddard notes pointedly that this mulatto leader “had torn out the eyes of his wretched prisoners with a corkscrew and had been guilty of unspeakable outrages upon white women.” The mulatto’s vicious crimes against Whites were nothing in comparison with the enormity of the racial insult uttered by the White military officer.

Stoddard contrasts two of the Jacobin commissioners. Sonthonax is described as personally corrupt and unprincipled, acting against his White racial brethren for personal gain. On the other hand, Polverol was highly principled: his “Jacobinism, though fanatical, was sincere, his personal honesty was never questioned, and ripening years brought some insight and reflection in their train.”

This contrast also doubtless applies to the behavior of contemporary Whites who eagerly go along with the multicultural agenda of displacing White people and their culture. There are many Sonthonaxes who earn very good salaries because they are public liberals—Whites who by their every statement and action express support for the multicultural zeitgeist. Because the multicultural revolution is far advanced at this point, there are many lucrative opportunities for those willing to publicly utter the sorts of niceties needed to climb the ladder. An example that comes to mind occurred at Duke University where faculty who loudly condemned White men who had been falsely accused of raping a Black prostitute were rewarded by becoming deans and other high-level administrators of the university.[1] This incident is particularly remarkable because the behavior of these faculty cost the university a great deal of money when the victims later sued the university.

On the other hand, there are doubtless a great many Polverols as well in the contemporary West, intent on punishing Whites whom they see as violating principles of moral universalism. They see massive non-White immigration and the decline of Whites as moral imperatives, and their views are constantly drummed into them by the mass media, the academic world, and the political class. Like the nineteenth-century Transcendental idealists, they ignore the realities of human nature, preferring to envision a utopian society expunged of evil.

It’s interesting that Whites are the only group to exhibit principled attitudes and behavior in the world depicted by Stoddard. When he obtained power, Toussaint L’Overture brutally enslaved his own people. Instead of being owned by Whites, they were now slaves of the Black oligarchy that dominated Haiti. “Shirkers and rebels were now publicly buried alive or sawn between two planks.”

The hatred toward the White colonists by other Whites was palpable. During the height of the Reign of Terror in France, colonists sent home were greeted, in the words of one such unfortunate, with “a furious hatred …. A hatred so intense that our most terrible misfortunes did not excite the slightest commiseration.” At the same time, mulatto and Black delegates from San Domingo were greeted with delirious applause.

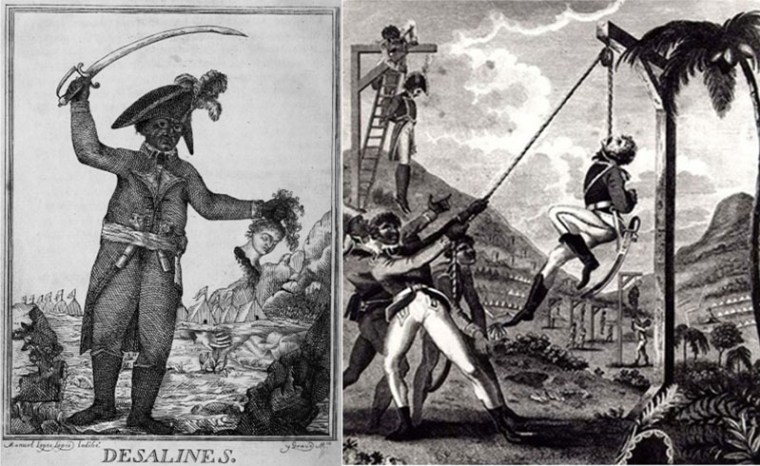

In the end, it was a war of racial extermination. The French under Napoleon returned and were winning the war, despite heavy losses from yellow fever. There was a common understanding that huge numbers of Blacks would have to be exterminated in order to restore the colony. But when the British intervened against the French, the White cause became hopeless. After a brief period when Whites were encouraged to return, they were exterminated under the leadership of the Haitian leader, Dessalines. “The destruction of French authority was but the prelude to the complete extermination of the white race in ‘la Partie François de Saint-Domingue.’” Like the White Jacobins and merchants, the British did not see the colonists as fellow Whites but as enemies, in the case of the British, because they were French.

Conclusion

The main message here is that individualism has served Whites well in enabling societies based on free markets, science, trust and innovation. Individualist European societies created the modern world. However, there is a tendency to short-term thinking that enriches individuals and produces long-term disaster for Whites as a group. In San Domingo, the short-sighted planter class imported masses of Africans without thinking clearly what this portended for the future, especially in a society where ideologies of moral universalism were becoming influential. The same thing happened in the U.S. and elsewhere in the Western hemisphere where large numbers of Blacks were imported as slaves. The tensions from slavery continue to loom over American society as the U.S. becomes increasingly polarized along racial lines. A similar phenomenon continues to occur as wealthy business interests lobby to import ever more low-IQ workers—workers who will eventually become citizens, vote, become the clients of aggressive, anti-White ethnic activist organizations, and seek their interests by expanding government entitlement programs.

There is an obvious sense in which the moral idealism so typical of the Western intellectual tradition can be fatally maladaptive. In the contemporary world of political correctness defined by the multicultural left, moral ideals incompatible with the interests of European-derived peoples are constantly trumpeted by elites in the media, the political class, and academic world. Such messages fall on fertile ground among European peoples, even as other races and ethnic groups continue to seek to shape public policy according to their perceptions of self-interest. The European proneness to moral idealism thus becomes part of the ideology of Western suicide.

With the exception of South Africa—another society where Whites eventually ceded power to Blacks and are now reaping the consequences in terms of violence, exploitation and insecurity, White populations are currently far safer than the tiny White population of San Domingo surrounded by a sea of hostile Blacks. However, the policies currently bringing millions of non-Whites into Western societies will ultimately create White minorities in all the societies that Whites dominated, including their ancestral homelands in Europe. Many of the peoples they are admitting have historical grudges against Whites for past evils like slavery, perceived anti-Semitism, etc. And in any case, the voting patterns of these groups are already clear—they are part of the ascendant non-White coalition centered in the Democratic Party in the United States and similar parties in other Western countries (e.g., the Labour party in the U.K). Whites should think about what happened in San Domingo before they continue embarking on their multicultural adventure. When Whites become vulnerable, as a result of these changes, the gloves will come off. The raw biological power of race for separating humans into mutually antagonistic groups will once again rear its ugly head, and the fine phrases of moral universalism that paved the way for White suicide will seem hollow indeed.

[1] William L. Anderson, “The Obama Administration’s Vicious Attack on Reade Seligmann.” LewRockwell.com, February 24, 2011.

Comments are closed.