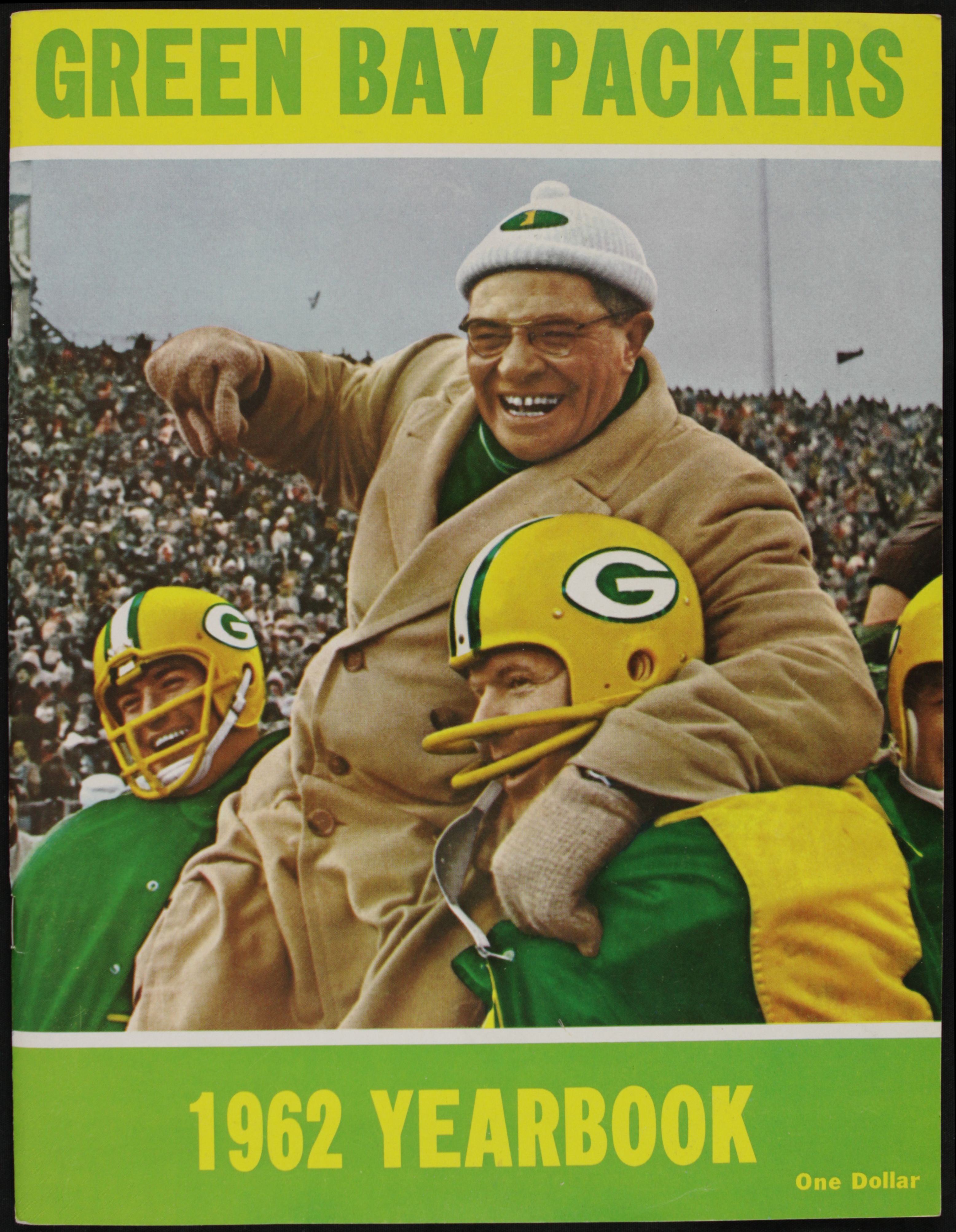

Vince Lombardi. Italian taskmaster.

Football coaches provide one of the purest examples of true leadership in America, especially in the period since World War Two. This idea was slow to dawn on me, but eventually I realized that these men command all-male cohorts, train them to practice a violent craft in a quasi-brotherhood, and enjoy virtually dictatorial powers in doing so. Where else can a man claim this type of authority? In this era of hegemonic Cultural Marxism, even the armed forces don’t get to wallow in unfettered masculine violence. Modern officers have to manage and coordinate women, transsexuals, and homosexuals, with all the politically correct minefields that surround them. Football coaches do have to be more “sensitive” these days, but when most of them were active, it was a much different, less constricted world. These men, I found, had quite a few common traits—excellent ones—that apparently led to their success, and also, I would suggest, exhibit their racial essence in action.

I certainly do not consider football itself to be very important. Indeed, it is often a distraction from the important issue of racial survival, its attraction explained by the attraction that men have to “a violent craft in a quasi-brotherhood.” But these men nevertheless provide us with a certain physiognomy of race—a portrait of race in action, if you will. And a telling aspect of traditional American culture.

These men exercised leadership in a manner peculiar to White culture. They shared a handful of crucial attributes that are common to many leaders, but they added to them a Faustian knife’s edge in their quest for glory and fame and championships. One can think of football coaches as like leaders of Indo-European war groups, intent on conquest and—more importantly—enduring fame—the “fame of a dead man’s deeds.”. These attributes include the confidence to insist on total control in their field of operation, an extraordinary and demanding attention to detail, high intelligence, and a restless, individualistic creativity that craves the next breakthrough, the next leap forward. This last quality is the Faustian edge that, in different hands and different realms, has seen Western man best the field in every higher endeavor.

RACE OR ETHNICITY

My Method

I decided to look at the top tier of professional football coaches and find traits common to them that might express race. I chose four lists of “greatest NFL coaches” on the Internet (ESPN, Athlon Sports, Fox Sports, and Bleacher Report) and combined them to arrive at a consensus top twelve. Two of the lists named twenty-five men; another had twenty, and the last, sixteen. I will not waste time discussing these rankings; I simply took them as they are for the purposes of this study. Here are the greatest pro football skippers of all time:

(The number following their names is the total for their rankings in the four lists; the smaller the number, the higher the ranking.)

- Vince Lombardi: 6

- Don Shula: 12

- Bill Walsh: 13

- Bill Belichick: 14

- Paul Brown: 20

- George Halas: 28

- Chuck Noll: 28

- Tom Landry: 30

- Joe Gibbs: 33

- Bill Parcells: 38

- Earl “Curly” Lambeau: 45

- John Madden: 51

Race/Ethnicity

I compiled biographical data for each man, and their national origins. I found the nationality of each parent of these men, and thus tabulated twenty-four separate national derivations. They are as follows, with the name of the coach followed by the maiden name of the mother, and then the nationalities of the father and the mother:

- Lombardi/Izzo Italian/Italian

- Shula/Miller Hungarian/ /Hungarian

- Walsh/Mathers Irish/German[i]

- Belichick/Munn Croatian/English

- Brown/Sherwood English/English

- Halas/Poledna Czech/Czech

- Noll/Steigerwald German/German

- Landry/Coffman French/German

- Gibbs/Blalock Scot/English or Scot[ii]

- Parcells/Naclerio Irish/Italian[iii]

- Lambeau/Latour French/French

- Madden/Flaherty Irish/Irish

These are the totals of the nationalities:

English: 3 or 4 (British Isles: 9)

German: 4

Irish: 4

Italian: 3

French: 3

Czech: 2

Hungarian: 2

Scottish: 1 or 2

Croatian: 1

Some things stood out right away—all were White men; almost all had blue or grey eyes; almost all of them had very demanding and strict parents; many of them were overtly religious (a majority were Catholic and two others were fervent Protestants). Eastern and southern Europeans were well-represented considering their percentage of the US population: the greatest, Vince Lombardi, was a swarthy descendant of Southern Italians; Don Shula was full-blooded Hungarian; George Halas was a Czech. Before I began, I unthinkingly assumed almost all of them would be British or Germanic.

Only 13 of the 24 parents originated from the British Isles or the German-speaking lands. (The Germans gave this country more immigrants than any other nation until Mexico surpassed them in recent times.) That is much less than one might expect given the demographics of America at the time, but this can be explained by the small sample we are working with. It is also an indication that great leadership qualities potentially adhere in all the Caucasian peoples.

One Jew (Marv Levy) and one Black (Tony Dungy) placed just outside the top twelve. One other Jew placed further down on two of the lists (Sid Gillman), but in one of them only as an innovator, not as a coach. One other Black (Mike Tomlin) made an appearance, but only on a single list (he placed 19th). Tony Dungy, who was a very good leader (and a devout Christian), doesn’t look like a pureblooded Black man, but I could find no confirmation of that.

Of course, these men were very close genetically, since they all have their roots in Europe.[4] The farthest point east is Hungary, the farthest south, Southern Italy. There were no Scandinavians, none from the Iberian Peninsula, and no Poles. Among the areas from which these men derived, southern Italy seems to be the most distant genetically from the rest, but the man whose roots came from there—Lombardi—ranks as the greatest of all. Hungary (Don Shula) actually fits pretty well within the genetic range of Western Europe, at least according to the above link.

Because these men were all White, we lack the material for a direct comparison with another race. Therefore, we will look at the common personal characteristics of these men. We will look not at genetics or race per se, but at the expression of race through character.

Bill Parcells. Irish and Italian. Jersey guy: smash-mouth football.

Blue Eyes

First, however, I will pause at one genetic marker: ten of these twelve men had blue or light eyes. Lombardi and Lambeau were the exceptions. (As best I could make out, at least, squinting at Internet images.)

Eight of these men had parents of the same nationality. When they were born, in the first half of the twentieth century (Belichick was the last born, in 1951), in-group marriage by nationality was the norm. That pattern broke down during the lives of these men, and American whites began to blend. Lombardi married a German girl, Halas a German too; Bill Walsh married an Italian. This phenomenon, as well as mass non-White immigration, had a big impact on the number of Americans with blue eyes, according to a 2002 study:

About half of Americans born at the turn of the 20th century had blue eyes, according to a 2002 Loyola University study in Chicago. By mid-century that number had dropped to a third. Today only about one 1 of every 6 Americans has blue eyes, said Mark Grant, the epidemiologist who conducted the study.

A century ago, 80 percent of people married within their ethnic group … . Blue eyes – a genetically recessive trait – were routinely passed down, especially among people of English, Irish, and Northern European ancestry. . . . As intermarriage between ethnic groups became the norm, blue eyes began to disappear, replaced by brown.

The influx of nonwhites into the United States, especially from Latin America and Asia, hastened the disappearance. Between 1900 and 1950, only about 1 in 10 Americans was nonwhite. Today that ratio is 1 in 3.

To go from fifty percent blue eyes in 1900 to about seventeen percent today is a drop of sixty-six percent, a huge decline. It is an indication, if any more were needed, that the survival of the White race and its astoundingly wide range of phenotypes—including the most breathtakingly beautiful specimens to ever walk the earth—is frighteningly precarious. (I’m doing my part to fight the trend: I’m the only one of my siblings to have blue eyes, but all my children do.)

John Madden. Irish. Viking?

THE EXPRESSION OF RACE IN PERSONAL CHARACTER

These twelve coaches show that great leadership correlates with certain singular personal attributes. Character (the mental and moral qualities distinctive to an individual, fashioned by the decisions of the will, inescapably related to the presence or absence of virtue) is the most important factor, but upbringing is quite important in fostering these qualities. Naturally, race is a vital underlying foundation that makes these personal traits possible, and, although it does not determine them in any one person, it does produce them with greater frequency in certain populations. The combination of all of these traits is classically—and probably uniquely—European and Faustian.

Strict and Demanding Parents

Parenting exerts an environmental influence but it reflects the genetic characteristics of both parents and children (passive, active, and evocative genotype-environment correlations). Almost all of these men had very demanding parents. Many of them also had cold or distant parents. Such parental behavior obviously pushes a child (at least those with the inner gumption to respond positively) to search within himself for springs of motivation and self-sufficiency. These men grew up with great expectations hanging over their heads, and little emotional support; yet they fulfilled those expectations.

Let us go through some examples:

Vince Lombardi, who led the Green Bay Packers to six championships in nine years in the 1960s with a mixture of exacting toughness and careful pedagogy, had a father who could be easy-going.

Vince Lombardi: Italian taskmaster

His mother Matilda was another matter. She “was nervous and domineering, barking out orders. Her family creed was that there was no time for lolling around.” She evinced “intense perfectionism,” and, when correcting her offspring, “She would hit first and ask questions later,” recalled a daughter.[5]

Bill Walsh. German and Irish. “The Genius”

Bill Walsh, who led the San Francisco 49ers to three Super Bowl wins with his offensive wizardry, was born in the Great Depression. Bill later related how his father had him work in his body shop on weekends at a tender age:

“He’d give me a dollar every now and then when he thought I did a particularly good job. What stuck was the level of detail he demanded from me. His expectations were hard and stark. It wasn’t like, ‘Maybe you better try to.’ It was ‘Get that goddam thing over here and line it up right’ … He’d blow his stack if he thought you screwed up …”[6]

Chuck Noll, who fashioned a dominant dynasty with the Pittsburgh Steelers in the 1970s, had a father who “belonged to a family of strivers possessed of an indefatigable work ethic and an unsentimental resolve.” His mother Kate “was strict and flew off the handle easy,” remembered a daughter. She never expressed the love she had for her children, but she provided them with everything they needed.[7]

Tom Landry headed the Dallas Cowboys for twenty-eight years, launching them into popular fame as “America’s Team” with two Super Bowl wins. Neither of his parents was “ever overtly affectionate,” but he never doubted their love for him. His mother Ruth (nee Coffman) had an “eye for detail and demanding perfectionism,” and rooted her children in her values.[8]

Bill Parcells, who earned a reputation as a coach who could instantly turn a loser into a winner, had parents who demanded “Toughness and perseverance . . . at all times.”[9]

And so on. The only exception to this pattern seems to be John Madden. I could find no description of his parents as demanding or tough.

Note also the word “perfectionism.” Such a great concept: a concern to make things perfect. So White.

Autocratic Methods

These men were convinced they could succeed if everyone just got out of their damn way. Therefore, they insisted on having total control. So many inferior people demand this type of power without other needed qualifications, but what we’re seeing here is not mere willfulness; this is a high order of leadership, born of confidence and a thorough, painstaking knowledge of their craft.

Lombardi was notorious for demanding strict control; he “was not inclined to cede power to his assistants or anyone else.” When he was negotiating his initial contract with the Packers he told the board of directors, “I want it understood that I am in complete command.” If the president of the board “still harbored notions of being the overseer, Lombardi quickly disabused him of those by usurping his parking space.”[10]

Paul Brown, who led the Cleveland Browns to multiple championships in the 1940s and 1950s, was “a football genius who demanded complete control. . . . He could . . . be a dictator within the realms of his football world, and his genial disposition would turn frosty when confronted with a question to his rule.” His leadership of the Browns was “an autocracy, a dictatorship …” One player said of him, “Paul is a lot more than a coach. . . . He signs you to a contract; he coaches you, . . . he tells you what to eat; and he tells you when to get up and when to go to bed.”[11]

George Halas, founder of the Chicago Bears and an architect of the National Football League, was “the original grizzly . . . surly, snarly, sinister, and smart.” He was a “hard man, a true godfather who saw fit to run his team, his league, and his family in his own image.” “Telling other men what to do . . . was something George Halas did as well as any commander who ever led forces into combat.”[12]

Bill Belichick, the present-day genius heading the New England Patriots dynasty, “did the things he wanted to do the way he wanted to do them, because in any given instance it was something he had thought about for a long time, and he had decided his way was right . . . Almost nothing could change him and make him act differently . . .”[13]

Curly Lambeau founded the Green Bay Packers in 1919 and ran the organization for decades. “He started it, picked the players, provided the drive, motivation and ran it with an iron hand. . . . He alone found the players he wanted, negotiated their contracts, handled team travel and designed team uniforms.”[14]

Demanding and Prickly Attention to Detail

Vince Lombardi is probably the greatest paragon of these qualities. After his first year in Green Bay, even though it was successful (especially compared to the records of the abysmal teams that preceded him), he came into camp in 1961 more motivated than ever. He famously “began a tradition of starting from scratch. . . . He reviewed the fundamentals of blocking and tackling, the basic plays, how to study the playbook. He began with the most elemental statement of all. “Gentlemen,” he said, holding a pigskin in his right hand, “this is a football.””[15] That year they won the NFL Championship, but he never ceased to painstakingly teach the most elemental parts of the game.

Don Shula, head of the Miami Dolphins from 1970–1995 and winner of two Super Bowls, was no different. A 1985 New York Times article described how Shula “knows every assignment of every player on every squad. He knows every rookie’s name, his background and his best times in the 40-yard dash. . . . Unlike some top coaches who ride around in golf carts and bark orders, Shula directs every drill on the field, pointing out a lesson to be learned from every play.”

Bill Belichick “was the king of Post-it notes. Nothing slipped through the cracks with him. In attention to detail he was a lineal descendant of some of the most obsessed men in America, those great NFL coaches.”[16] He was demanding too. A former player said of him, “He’s not going to be your best friend. He is demanding of you every second that you are in that facility and partially when you’re out of the facility also. He demands your concentration, your intelligence. . . . Everything that you can put into a football game, he demands it of you.”

For Bill Walsh, “no detail” in the entire organization “was beyond his purview and he exercised an almost rigid adherence to his own vision. Bill wanted what he wanted, wouldn’t settle for less, and could be, in the words of one of his coworkers, “a real prick about it.” He expected the headquarters to be neat and staged regular inspections. . . . He could not walk past a crooked picture hung on the wall, compulsively straightening every one he encountered.”[17]

Intelligence and Creativity

The creativity of these men was marked by intense ambition; they had no compunction about upsetting the established way of doing things to make their individual mark. They studied their opponents on film for endless hours, wracked their brains, and wrung subordinates dry to find even the slightest advantage, and they did this for decades of late nights and early mornings. Almost all of these men did indeed forge genuine revolutions in tactics that gave them that coveted advantage.

Curly Lambeau was an “imaginative, impatient visionary with vast energy who had an indomitable will to win.”[18]

One of the greatest innovators was Bill Walsh, whose legacy “is . . . that he changed offense. Offense before Bill Walsh was . . . run defense, establish the run. Run on first down, run on second down, and if that doesn’t work, pass on third down. Bill Walsh passed on first down, passed on second down and used that to set up the run,” . . . John Madden said. “People use the word genius and we usually scoff at that. In his case, I don’t think you can scoff at it.”

Paul Brown, often called the father of the modern game of football, had an impressive list of original developments:

- Calling plays from the sideline;

- Testing players for IQ and personality;

- Giving players written exams on the playbook;

- Scouting opponents by watching film;

- Hiring full-time assistant coaches;

- Holding highly organized, pre-planned drills;

- Inventing the draw play.[19]

Tom Landry was a renowned trailblazer: Landry . . . engineer[ed] the shotgun formation, computer ratings of college prospects, and film breakdowns. “When we approached him about computers, he was on board with it immediately,” [Gil] Brandt said. “His flexibility and understanding were superb.”

“Students of technical football will remember Landry for his innovations: the Flex defense; the shifting spectrum of multiple sets and formations, with players in motion in all directions . . . his “influence” blocking scheme that relied more on guile than sheer power. In 50 years they might look at Landry’s old playbooks and say what an intriguing mind the guy had . . .”

Bill Parcells, an exception to this thirst for novelty, commented on his fellow coaches:

The dilemma that some young coaches have is that they’re concerned with being viewed as ‘gurus,’ or whatever word you want to use. . . . When they choose their methods, they want them to be ‘aesthetically pleasing.’ . . . They want to be creative. They want to be the next Bill Walsh. They have computers, they have four, five hundred plays. . . . They have schemes, they have wrinkles. It’s a highly technical world they live in . . .

CONCLUDING THOUGHTS

These men clearly illustrate the White pattern of high achievers: great internal drive, a desire for fame and success, combined with intelligence and restless ingenuity.

The dynamic individuality and ambition of these men created periodic revolutions in the style and tactics of football. The game bears little resemblance to football as played circa 1920, when the NFL was founded, and it is continually changing. This phenomenon mirrors on a much more modest scale the convulsive, fertile revolutions that Faustian White men have periodically generated in the realms of economic systems, philosophical paradigms, and political ideologies.[20] Other races would not have reacted to the sport of football in the same manner, because they’re . . . different. East Asians, in all likelihood, would have thought it more important to play the game according to static, time-and-ancestor-honored patterns; with their collectivist mentality they probably wouldn’t have upset the cart to gain a short-term advantage. To gain insight on Black sporting patterns, I searched the internet to find examples of African sports to help me draw some lessons, but I went no further than a web page that listed the eight most popular sports in Africa—all of them originated by Whites, except perhaps wrestling.

As for non-Whites in American football, two Jews and two Blacks made it onto these lists of top coaches, the former overrepresented, the latter a bit underrepresented on the basis of population. First, Jewish representation might be higher, except that most coaches played the game first, and few Jews played in the NFL. Wikipedia lists only seven Jews who headed professional football teams. Jews were much more involved in basketball, possibly because it was a more urban sport, and three rank among the all-time great National Basketball Association coaches: Red Auerbach, Red Holzman, and Larry Brown. With their intelligence, Jews certainly could be successful leaders of football teams. However, few join the sport. At present there are no Jews at the head of pro teams.

Of course, Jews are massively over-represented in the ownership of pro sports teams. Jews own about a third of the NFL teams: the Atlanta Falcons (Arthur Blank, founder of Home Depot and famous for his hang-dog look as his team lost a 25-point lead to the Jewish-owned Patriots in Super Bowl LI); Indianapolis Colts (Jim Irsay, who is half-Jewish), Miami Dolphins (Stephen Ross, a philanthropist who has given his alma mater the University of Michigan, a major bastion of the Left, $380 million); Minnesota Vikings (the Wilfs and David Mandelbaum); New England Patriots (Robert Kraft); New York Giants (Steve Tisch); Oakland Raiders (Mark Davis, son of the flamboyant founder Al Davis); Philadelphia Eagles (Jeffrey Lurie); Tampa Bay Buccaneers (the Glazer family); and the Washington Redskins (Dan Snyder).

The first Black to become head coach in the NFL in modern times was Art Shell in 1989. Whatever the case may be, two Black coaches have won Super Bowls, the above-mentioned Tony Dungy and Mike Tomlin. In three decades, they are the only two to have distinguished themselves as leaders of NFL teams. Tony Dungy had a great career; however, there is some reason to think that Mike Tomlin regularly gets out-coached in the playoffs, especially by Bill Belichick.

Finally, there is religion. Eight of these men were Catholics (Lombardi, Shula, Walsh—a late convert; Halas, Noll, Parcells, Lambeau, and Madden) and another two, Landry and Gibbs, were fervent Protestants. Halas, Lombardi, and Shula were daily attendees at Mass. All in all, it seems fair to say that religious faith can help to enhance discipline and order in a person’s life; it certainly provided inspiration for many of these men, particularly Lombardi, Shula, Halas, Noll, Landry and Gibbs.

Well, there we have it. Even football bears the stamp of the Faustian spirit, and its greatest captains express the racial imprint of their glorious forebears, albeit in a humbler way. As always, the lessons we draw from all this remain pretty straightforward: work as hard as you can in your own sphere. And marry a gal with blue eyes.

Sources

[1] Mathers is usually an English name but Walsh’s biographer David Harris (see below) says the family was German.

[2] These are based only on surnames.

[3] Parcells’ father’s birth name was O’Shea.

[4] A “European subrace evolved in Europe, remaining very stable genetically with minimal outside racial mixing . . .” Ricardo Duchesne, Faustian Man in a Multicultural Age. (London: Arktos Media, 2017), 68.

[5] David Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered: A Life of Vince Lombardi. (New York: Touchstone Books, 2000), 22.

[6] David Harris, The Genius: How Bill Walsh Reinvented Football and Created an NFL Dynasty. (New York: Random House, 2008), 29.

[7] Michael MacCambridge, Chuck Noll: His Life’s Work. (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2018), 2-4.

[8] Mark Ribowsky, The Last Cowboy: A Life of Tom Landry. (New York: Liveright Publishing, 2014), 19.

[9] Carlo DeVito, Parcells: A Biography. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2011), 9.

[10] Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered, 207-08.

[11] Andrew O’Toole, Paul Brown: The Rise and Fall and Rise Again of Football’s Most Innovative Coach. (Cincinnati: Clerisy Press, 2008), vi, 1.

[12] Jeff Davis, Papa Bear: The Life and Legacy of George Halas. (New York: McGraw Hill, 2005), 9.

[13] David Halberstam, The Education of a Coach. (New York: Hyperion, 2005), 22.

[14] David Zimmerman, Lambeau: The Man Behind the Mystique. (Hales Corners, WI: Eagle Books, 2003), 24.

[15] Maraniss, When Pride Still Mattered, 274.

[16] Halberstam, The Education of a Coach, 25.

[17] Harris, The Genius, 67-68.

[18] Zimmerman, Lambeau, 27-28.

[19] George Cantor, Paul Brown: The Man Who Invented Modern Football. (Chicago: Triumph Books, 2008), 3-4.

[20] See Duchesne, Faustian Man, 73-75, for a good overview of this idea. In contrast to Europe, “the intellectual traditions set down in ancient/medieval times in China, the Near East, India, and Japan would persist in their essentials until the impact of the West brought some novelties.”

Comments are closed.