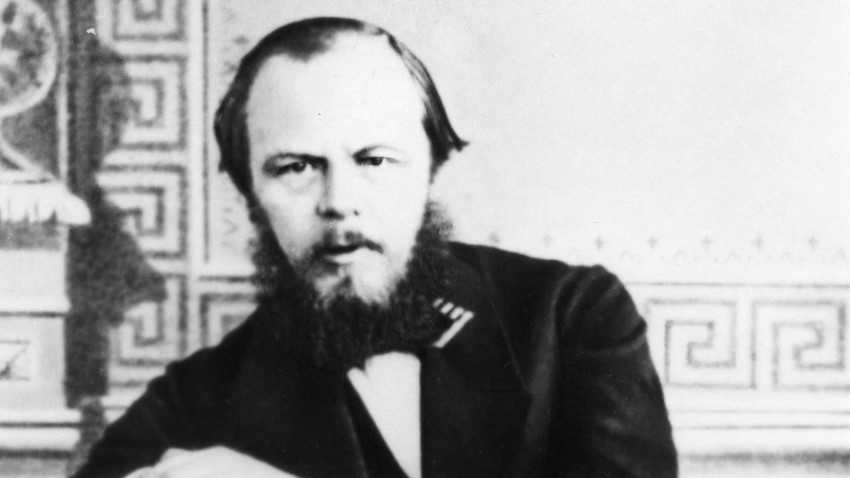

Reply to Jordan Peterson on the Jewish Question — From His Heroes Part Two: Dostoevsky

Jordan Peterson references Fyodor Dostoevsky in almost every interview, talk, or text he delivers —perhaps even more than he refers to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn. His admiration for Dostoevsky is considerable and is made clear in 12 Rules for Life. In 12 Rules, Peterson refers to the Russian author as (p.68) “incomparable,” and (p.137) “a wise and profound soul” possessing “great generosity of spirit.” Peterson describes Crime and Punishment (p.83) as “perhaps the greatest novel ever written,” and Dostoevsky himself (p.136) as “one of the great literary geniuses of all time.” He adds to the latter praise that the author “confronted the most serious existential problems in all his great writings, and he did so courageously, headlong, and heedless of the consequences.”

Perhaps even more so that was the case with Solzhenitsyn, Fyodor Dostoevsky has been pilloried in recent decades as an ultra-nationalist anti-Semite who believed Jews “had harmed and continued to harm the foundations of Russian society and culture.

Peterson, it will be recalled, has described anti-Semites as individuals who “claim responsibility for the accomplishments of [the] group [they] feel racially/ethnically akin to without actually having to accomplish anything [themselves].” Clearly an important point needs to be reconciled by Peterson: namely the outstanding literary accomplishments and political stances of Dostoevsky (even in Peterson’s own gushing estimation), and Peterson’s assertion that anti-Jewish critique rooted in nationalist sensibilities is merely a form of psychological escapism for those keen to avoid accomplishing anything for themselves. Surely it is self-evident that Dostoevsky, like Solzhenitsyn, was a man not only of accomplishment, but of remarkable, extraordinary accomplishment. What were Dostoevsky’s attitudes to Jews and the Jewish Question, and how would he respond to Jordan Peterson?

The two most septic academic treatments of the Russian author are David Goldstein’s 1981 Dostoyevsky and the Jews,[1] and Joseph Frank’s 2002 Dostoevsky, The Mantle of the Prophet, 1871–1881. Both writers exude Jewish identity in their treatment of Dostoevsky’s published and private writings on Jews, an emotionality that appears remarkably commonplace among Jews as a whole. Reviewing some material penned by Jews on the Russian writer, I was struck by their similarity to the fraught sensitivity of Anthony Julius to the work of T. S. Eliot. The core problem is that, while Jews (and also apparently Jordan Peterson) often comfort themselves with the delusion that their critics are intellectually and socially inferior, they appear to experience great psychological trauma when faced with the reality that their harshest and most insightful critics are often men of great ability and genius. An excellent example of this phenomenon, along with the Jewish obsession with historical enmities, can be observed in these comments, posted at a Jewish website as part of the question “Should a Jew read Dostoevsky?”:

There was a period, while I was in college I think, when I was very into Russian short-story writers and playwrights. I read quite a few, and was very impressed — until I came to Nikolai Gogol, and a story in which described the glory of the Cossacks. I couldn’t read any further; the Cossacks were murderous butchers who slaughtered my ancestors. Of course, if Jews were to shun all writers who hated us, we would be left with slim literary pickings; a quick thumbing through Allan Gould’s What did they think of the Jews? shows that we would lose a great deal of Western culture, including figures like Lord Byron and Joseph Conrad and Jack London.

Similarly, Haaretz writes of Joseph Frank’s Dostoevsky biography: “As a Jew, Frank cannot be nonchalant about the primitive anti-Semitic elements in Dostoevsky’s writing,” describing Frank’s exploration as a “painful saga.” This is fully in keeping with observations made in my 2014 essay “Reflections on Aspects of Jewish Self-Deception,” in which, referring especially to the works of academic activists Anthony Julius and Robert Wistrich, I noted:

Jewish-produced accounts of anti-Semitism often begin or conclude with maudlin claims that the subject is ‘difficult,’ ‘emotional,’ or ‘trying’ for them to approach. At the extreme end of the spectrum one finds Anthony Julius who describes studying the subject at the conclusion of Trials of the Diaspora: A History of Anti-Semitism in England as “immersing oneself in muck. Anti-Semitism is a sewer.” Wistrich refers to his “long-standing concern with the nature of anti-Semitism,” and describes his study of the subject as a “difficult enterprise,” which was “painful, often shocking.”

Goldstein and Frank, like Julius, are quite typical of Jewish literary critics who emerged from elite colleges in the mid-to-late twentieth century. In The Professionalization of History in English Canada (2005), Donald Wright notes that between the 1940s and early 1960s many WASP literary academics were taken aback by the aggressive and highly antagonistic attitude of their Jewish students. In just one example, a Canadian academic named Frank Underhill included in one student report the following comments: “He is a Jew, with a good deal of the Jew’s persecution complex, and this makes him unduly aggressive and sarcastic in discussion and writing.”[2]

Having read the majority of the offerings from Goldstein and Frank, I don’t think I could improve upon “unduly aggressive and sarcastic” as suitable descriptors. The same could be said of Peterson’s lazy dismissal of anti-Semitism as a tool of the unaccomplished.

Jews hardly feature in the fictional canon of Fyodor Dostoevsky, making him in some ways a less obvious target for attack than Solzhenitsyn, who was once berated by Jewish activist academic Mark Perakh because “a disproportionately large number of unattractive Jews appear in his work.” Perakh’s stance reminded me strongly of the activism of Anthony Julius in relation to representations of Jews in English literature. On this point, I’ve commented previously:

What Julius, and the horde of other Jewish literary ‘scholars,’ are really asserting here is their antagonism towards anything but positive reflections of Jews in literature, which is not only arrogant and unreasonable, but also further indication of a pathological level of ethnocentrism. Their efforts have the dual function of staining the legacy of the English literary past, and shackling authors in the present, who would feel constrained to avoid having a negatively portrayed Jewish character in their works.

The primary grounds for the Jewish attack on Dostoevsky appear to be the character of Isai Fomich Bumstein in The House of the Dead [for the sake of accuracy I should note my own 1980s Soviet Union edition/translation bears the less common title Notes from the Dead House]. It can be asserted with reasonable certainty that Isai Bumstein is Dostoevsky’s only real attempt to include a fully-fledged Jewish character in his works. Since The House of the Dead was strongly autobiographical, we can also assume that the character was based on a real Jew encountered by the author during his detention in a Siberian work camp. It appears, however, that Isai Bumstein, despite cutting a solitary figure, is one Jew too many for some.

Isai Fomich is described as the camp’s jeweler and foremost moneylender. A figure of fun, but with dark and even satanic undertones, Dostoevsky describes this, the only Jew in the camp, as “the spitting image of a plucked chicken. He was a man, no longer young, about fifty, short and weak, cunning yet positively stupid. He was arrogant, impudent, and at the same time a terrible coward.” Bumstein was confined to the jail for murder and uses his talent in making and trading jewelry to “wriggle out of his hard labour.” The book’s most extensive discussion of Bumstein takes place in the build up to a Dante-esque scene of claustrophobic horror in the local bath house, in which Bumstein takes a prominent and quasi-demonic role reminiscent of the Judge in the final act of Cormac McCarthy’s 1985 Blood Meridian (although no literary scholars seem to have discovered the link between the characters — despite McCarthy’s known affinity with Dostoevsky; further parallels between these two characters may be found in their unusually pale complexions, supernatural cunning, and numerous authorial allusions to their hairlessness).

Bumstein’s first act on entering the gaol is to barter for the “filthy, ragged summer trousers” of a fellow inmate, which he then takes in pawn and negotiates interest on. Sullen on entering the jail, he now “suddenly roused himself and started feeling the rags with his fingers in a most business-like manner. He even held them up to the light.” The deal concluded, “Isai Fomich re-examined the things he had taken in pawn, folded them carefully, and stowed them away inside his sack.” With the other inmates later in his thrall, he sings a song that he later confesses to be obliged to sing as a Jew in “moments of triumph over foes.”

Bumstein is described by Dostoevsky as having an easy time in confinement, enjoying privileges and all the trappings of elite status:

He was not at all hard up and, in fact, even lived quite prosperously, saving his money and lending it at interest to the whole prison. He had his own samovar, a good mattress, cups, and a complete set of crockery. The town Jews did not snub him and, on the contrary, they patronised him. On Saturdays, as allowed by the rules, he would go out under guard to the town’s synagogue.

Bumstein’s final appearance in the book takes place in the local bath house where eighty prisoners are essentially crushed into a space twelve paces by twelve where they must steam and wash themselves. The scene is oppressively and horrifically claustrophobic and is punctuated by the figure of Bumstein looming over all, “laughing his head off from the highest steam-shelf.” Impervious to the heat and noise bringing everyone else to near senselessness, “it seemed that no heat was enough to satisfy him.” The Jew uses his money to hire five attendants in succession to beat him with birch twigs, all of whom near the point of unconsciousness before rushing to revive themselves with cold water.

Bumstein “could indeed feel that he was indeed ‘on top’ of all the others. He had outdone them all. It was his moment of victory. And over all the noise, his shrill, mad voice was heard shouting out his aria: ‘La, la, la, la.’ It crossed my mind, that should we one day meet again in Hell, the scene would be very much the same.”

Dostoevsky’s The House of the Dead, like several of his other works, is indeed a work of literary genius. That such a great work also contains a very memorable, unflattering, and all too believable portrait of a work-shy Jewish moneylender is a source of much contemporary Jewish psychological disturbance. Another crucial problem is that, although Jewish criticisms have revolved around accusations of the employment of stereotypes, the book’s strong autobiographical origins, together with Dostoevsky’s commitment to realism, render the portrayal of Isai Fomich Bumstein all too difficult to dismiss or dispel. As this commentary in Haaretz concedes, “Dostoevsky, more than all the great authors of 19th-century Russia, derived his inspiration from real life, even from the front pages of the newspaper, to the point where the critics of his day felt that this excessive realism harmed his work.”

In “On the So-Called Jewish Question,” Jordan Peterson appears to contrast high IQ individuals who (relatedly) score highly on Openness to Experience and political liberalism with presumably lower IQ individuals who seeks solace for their personal lack of accomplishment in group identity, ethnic nationalisms, and, one assumes, anti-Semitism. Kevin MacDonald has already saliently pointed out that Israel is hardly typified by Openness to Experience and political liberalism, despite being populated with the group Peterson seems to regard as epitomizing the high IQ/Openness/liberalism trifecta. It’s interesting, though, that the life, career, and ideas of his hero Dostoevsky also offer a strong rebuttal to Peterson’s poorly thought out schema. Dostoevsky was certainly an ardent Russian nationalist with a keen sense of ethnic identity, but was also “perceived as a courageous and independent critic of the czarist government, unafraid of denouncing its misdeeds and corruption.” Dostoevsky was no blind authoritarian; and he was certainly no unaccomplished basement-dweller in search of identity.

In his later writings, published in his journal Diary of a Writer, Dostoevsky began to write with some regularity on Jews, and in at least one issue wrote at length specifically on the Jewish Question. The opinions put forth in these pieces contrast sharply with that offered by Prof. Peterson. In fact, Dostoevsky, reflecting arguments that were common in post-Enlightenment Europe, argues that it would be suicidal for Western civilization to abandon its religious, ethnic, and historical identities (White “identity politics”) in favor of modern fads (he names socialism, but one could as easily substitute Peterson’s dubious strain of liberalism).

[Jews] maintain their own close-knit identity. If the Jews are given equal legal rights in Russia, but are allowed to keep their ‘State within a State,’ they would be more privileged than the Russians. The consequences of this situation are already clear in Europe. … What if there were only three million Russians and there were eighty million Jews? How would they treat Russians and how would they lord it over them? What rights would Jews give Russians? Wouldn’t they turn them into slaves? Worse than that, wouldn’t they skin them altogether? Wouldn’t they slaughter them to the last man, to the point of complete extermination? … When only anarchy remains, the Yid will be in command of everything. For while the Jew goes about preaching socialism, he will stick together with his own.

Offering Jews full citizenship rights would be beneficial for Jews because they would still operate as a cohesive group in a nominally individualist society. This goes to the heart of Peterson’s liberal/individualist ideology. It can only work if everyone adopts it. When cohesive, ethnically networked and highly competent groups with their own interests remain in a nominally individualist society, they easily dominate the individualists and are able to shape the culture to conform to their interests. These interests need not, and often are not (e.g., policy toward Israel, mass immigration of non-White ethnic groups), the same as the interests of the individualists.

And on that note, we make way for Carl Jung.

[1] David Goldstein, Dostoyevsky and the Jews (Austin: University of Texas Press, 1981).

[2] Donald Wright, The Professionalization of History in English Canada (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2005), 95

Comments are closed.