Reply to Jordan Peterson on the Jewish Question — From His Heroes: Part Three: Jung

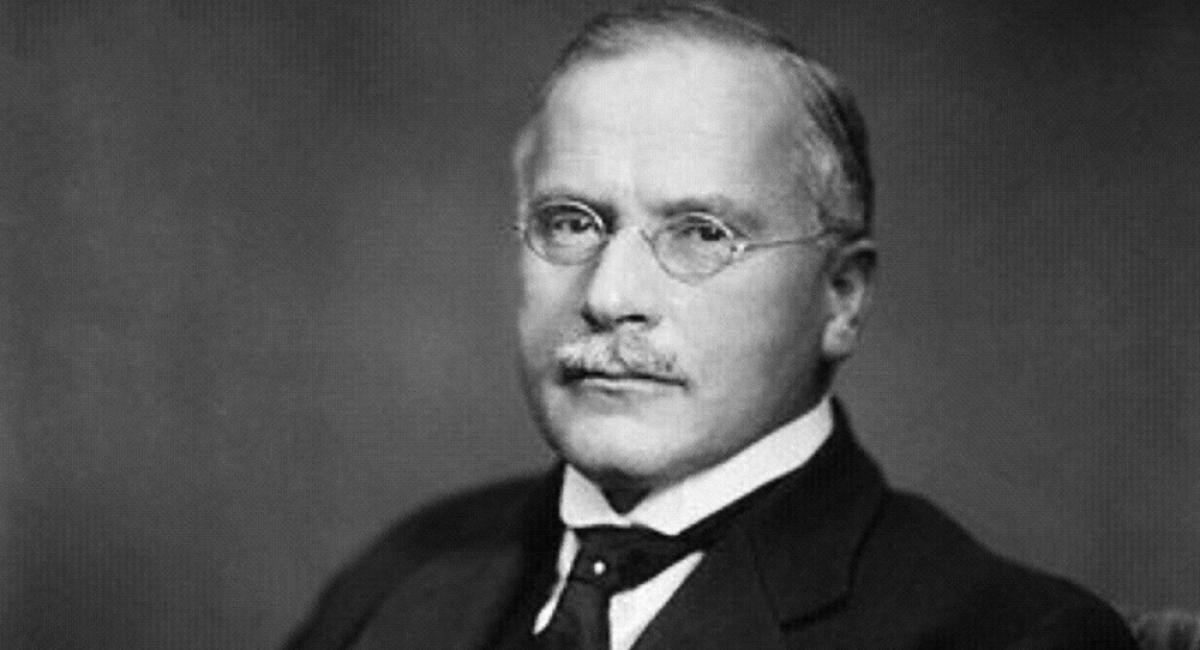

C. G. Jung

Go to Part 1: Solzhenitsyn.

Go to Part 2: Dostoevsky

A Reply to Jung.

Jordan Peterson references Carl Jung in almost every interview, talk, or text he delivers, and these references are especially frequent in his lecture series on the Biblical stories. In 12 Rules for Life (p.131), Peterson describes Jung as both a “great psychiatrist” and a “psychoanalyst extraordinaire.” Jung’s ideas about the subconscious and archetypes form the backbone of much of Peterson’s self-concept and public work. One therefore wonders what Jung would have made of Jordan Peterson’s “On the So-Called Jewish Question.”

To begin with, Jung would almost certainly object to Peterson’s implicit assumption that Jews are easily integrated parts in the machinery of Western civilization, equal or even superior in suitability to all others. Jung believed that Jews, like all peoples, have a characteristic personality, and he would have stressed the need to take this personality into account. Even in his own sphere of expertise, Jung warned that “Freud and Adler’s psychologies were specifically Jewish, and therefore not legitimate for Aryans.”[1] A formative factor in the Jewish personality was the rootlessness of the Jews and the persistence of the Diaspora. Jung argued that Jews lacked a “chthontic quality,” meaning “The Jew … is badly at a loss for that quality in man which roots him to the earth and draws new strength from below.”[2] Jung penned these words in 1918, but they retain significance even after the founding of the State of Israel. Even today, vastly more Jews live outside Israel than within it. Jews remain a Diaspora people, and many continue to see their Diaspora status as a strength. Because they are scattered and rootless, however, Jung argued that Jews developed methods of getting on in the world that are built on exploiting weakness in others rather than expressing explicit strength. In Jung’s phrasing, “The Jews have this particularity in common with women; being physically weaker, they have to aim at the chinks in the armour of their adversary.”[3]

Jung would probably have been doubtful regarding Peterson’s claims that Jews obtain positions of influence solely on their intellectual merits and because they score high on Openness to Experience. Jung believed that Jews were incapable of operating effectively without a host society, and that they relied heavily upon grafting themselves into the systems of other peoples in order to succeed. In a 1934 essay titled ‘The state of psychotherapy today,’ Jung wrote: “The Jew, who is something of a nomad, has never yet created a cultural form of his own, and as far as we can see, never will, since all his instincts and talents require a more or less civilized nation to act as host for their development.” This process of group development often involved ‘aiming at the chinks in the armour of their adversary,’ along with other flexible strategies.[4]

Jung also believed (in common with a finding in Kevin MacDonald’s work) that there was a certain psychological aggressiveness in Jews, which was partly a result of the internal mechanics of Judaism. In a remarkably prescient set of observations in the 1950s, Jung expressed distaste for the behavior of Jewish women and essentially predicted the rise of feminism as a symptom of the pathological Jewess. Jung believed that Jewish men were “brides of Yahweh,” rendering Jewish women more or less obsolete within Judaism. In reaction, argued Jung, Jewish women in the early twentieth century began aggressively venting their frustrations against the male-centric nature of Judaism (and against the host society as a whole) while still conforming to the characteristic Jewish psychology and its related strategies. Writing to Martha Bernays, Freud’s wife, he once remarked of Jewish women that “so many of them are loud, aren’t they?” and later added he had treated “very many Jewish women — in all these women there is a loss of individuality, either too much or too little. But the compensation is always for the lack. That is to say, not the right attitude.”[5]

It is likely that Jung would also have taken issue with the spirit of Peterson’s brief essay; namely, that it takes the form of a smug defense of Jews against alleged anti-Semitism. Peterson clearly locates Kevin MacDonald’s analysis of Jewish group behavior through history in the realm of “reactionary conspiracy theories.” Jung, meanwhile, was cautious about accusations of anti-Semitism, and he was “critical of the oversensitivity of Jews to anti-Semitism,” believing “one cannot criticise an individual Jew without it immediately becoming an anti-Semitic attack.”[6] It is certainly difficult to believe that Jung, who basically argued that Jews had a unique psychological profile and had developed a unique method for getting on in the world, would have disagreed with the almost identical foundational premise of Kevin MacDonald’s trilogy. In fact, Jung believed that playing the victim and utilizing accusations of anti-Semitism as a sword against their critics were simply parts of the Jewish strategy—a useful cover for concerted ethnocentric action in “aiming at the chinks in the armour of their adversary.” For example, after the war, in a 1945 letter to Mary Mellon, he wrote, “It is however difficult to mention the anti-Christianism of the Jews after the horrible things that have happened in Germany. But Jews are not so damned innocent after all—the role played by the intellectual Jews in pre-war Germany would be an interesting object of investigation”[7] Indeed, MacDonald notes:

a prominent feature of anti-Semitism among the Social Conservatives and racial anti-Semites in Germany from 1870 to 1933 was their belief that Jews were instrumental in developing ideas that subverted traditional German attitudes and beliefs. Jews were vastly overrepresented as editors and writers during the 1920s in Germany, and “a more general cause of increased anti-Semitism was the very strong and unfortunate propensity of dissident Jews to attack national institutions and customs in both socialist and non-socialist publications” (Gordon 1984, 51).[i] This “media violence” directed at German culture by Jewish writers such as Kurt Tucholsky—who “wore his subversive heart on his sleeve” (Pulzer 1979, 97)—was publicized widely by the anti-Semitic press (Johnson 1988, 476–477).

Jews were not simply overrepresented among radical journalists, intellectuals, and “producers of culture” in Weimar Germany, they essentially created these movements. “They violently attacked everything about German society. They despised the military, the judiciary, and the middle class in general” (Rothman & Lichter 1982, 85). Massing (1949, 84) notes the perception of the anti-Semite Adolf Stoecker of Jewish “lack of reverence for the Christian-conservative world.” (The Culture of Critique, Ch. 1)

These sentiments largely echoed comments Jung made in November 1933 to Esther Harding, in which he expressed the opinion that Jews had clustered in Weimar Germany because they tend to “fish in troubled waters,” by which he meant that Jews tend to congregate where social decay is ongoing. He remarked that he had personally observed German Jews drinking champagne in Montreaux (Switzerland) while “Germany was starving,” and that while “very few had been expelled” and “Jewish shops in Berlin went on the same,” if there was a rising hardship among them in Germany it was because “overall the Jews deserved it.”[8] Perhaps most interesting of all in any discussion of Jewish acquisition of influence, it appears that in 1944 Jung oversaw the implementation of quotas on Jewish admission to the Analytical Psychology Club of Zurich. The quotas (a generous 10% of full members and 25% for guest members) were inserted into a secret appendix to the by-laws of the club and remained in place until 1950.[9] One can only assume that, like other quotas introduced around the world at various times, the goal here was to limit, or at least retain some measure of control over, Jewish numerical and directional influence within that body.

Although he was, like Peterson, a proponent of psychological individuation and the cultivation of the individual subconscious, Jung would be unlikely to agree with Jordan Peterson’s dismissal of “identity politics.” Jung in fact believed that mass national movements under strong leaders could pave the way for energetic rebirth and renewal. In a radio broadcast from Berlin in 1933 he remarked:

Times of mass movement are always times of leadership. Every movement culminates organically in a leader, who embodies in his whole being the meaning and purpose of the popular movement. He is an incarnation of the nation’s psyche and its mouthpiece. He is the spearhead of the phalanx of the whole people in motion.[10]

In fact, Jung believed that “identity politics” was a positive that should be pursed to exclusionary lengths, and that multiculturalism would have potentially disastrous effects on Whites. For example, having spent some time examining the state of mental health in the United States, Jung attributed the “American complex” to the fact Whites were “living together with ‘lower races, especially with Negroes’.”[11] Jung undertook two trips to Africa with the express purpose of studying what he viewed as the most “primitive” human psychologies.[12] He afterwards asserted that “there is a danger in the mixture of races,” that the mulatto is “apt to be a bad character,” and that “miscegenation is the cause of many cases of insanity.”[13] Many Whites living among Blacks are confronted with a “source of temperamental and mimetic infection,” by which he means that the former will too readily begin to adopt the negative behaviors of the latter—a type of cultural contagion.

Conversely, for the astute, interacting with Africans and thoughtfully observing the deep differences between the races could provide a positive reinforcement of identity. Jung himself remarked that, while travelling through Africa, “I could not help feeling superior, as I was reminded at every step of my European nature.”[14]

This is a striking comment because it expresses the fact that the sense of racial difference is something that impresses itself on the subject from an external experience. This contrasts radically with post-modern and psychoanalytic theories of racial thought and “race prejudice,” which root the sense of racial difference in the inner world of the subject. This latter way of thinking is most radically the case in Jean-Paul Sartre’s Anti-Semite and Jew, where the French philosopher argues that the anti-Semite is not someone struck by the observation and experience of Jewish behavior, but rather someone whose inner anxieties and inadequacies drive the search for an external cause onto which to project the inner flaws. This is both pseudo-science and pseudo-psychology.

Examining Jordan Peterson’s assessment of the Jewish Question, we can only conclude once more that Peterson’s ideas share more in common with the post-modernist thought he claims to struggle against, than with the traditional Western intellectual tradition he claims to defend. Just to reiterate, this is Peterson’s account of the origins of anti-Semitism in the individual:

You can claim responsibility for the accomplishments of your group you feel racially/ethnically akin to without actually having to accomplish anything yourself. That’s convenient. You can identify with the hypothetical victimization of that group and feel sorry for yourself and pleased at your compassion simultaneously. Another unearned victory. You simplify your world radically, as well. All the problems you face now have a cause, and a single one, so you can dispense with the unpleasant difficulty of thinking things through in detail. Bonus. Furthermore, and most reprehensibly: you now have someone to hate (and, what’s worse, with a good conscience) so your unrecognized resentment and cowardly and incompetent failure to deal with the world forthrightly can find a target, and you can feel morally superior in your consequent persecution.

This could have been lifted directly from Sartre, Horkheimer, or Adorno. It’s pure Jewish psychoanalysis, mobilized for political ends. And it is the kind of thought that provides legitimacy and ideological firepower to the marginalization of White interests and the continuation of White cultural collapse.

Jung, of course, remained for a long time disturbed about the potential for such a cultural collapse among Whites, and he was particularly anxious about the experience of Whites forced to co-habit with large African populations. He warned: “the European, however highly developed, cannot live in impunity among the Negroes. … Their psychology gets into him unnoticed and unconsciously he becomes a Negro. There is no fighting against it.”[15] “Identity politics,” with ethno-racial foundations was, to Jung, a matter of racial and civilizational survival.

We turn finally to Friedrich Nietzsche.

[1] B. Cohen, “Jung’s Answer to Jews,” Jung Journal: Culture and Psyche, 6:1 (56-71), 59.

[2] Ibid, 58.

[3] Ibid.

[4] T. Kirsch, “Jung’s Relationship with Jews and Judaism,” in Analysis and Activism: Social and Political Contributions of Jungian Psychology (London: Routledge, ), 174.

[5] Ibid, 177.

[6] T. Kirsch, “Jung and Judaism,” Jung Journal: Culture and Psyche, 6:1 (6-7), 6.

[7] S. Zemmelman (2017). “Inching towards wholeness: C.G. Jung and his relationship to Judaism.” Journal of Analytical Psychology, 62(2), 247–262.

[8] See W. Schoenl and L. Schoenl, Jung’s Evolving View of Nazi Germany: From the Nazi Takeover to the End of World War II (Asheville: Chiron, 2016).

[9] S. Frosh (2005). “Jung and the Nazis: Some Implications for Psychoanalysis.” Psychoanalysis and History, 7(2), (253–271), 258.

[10] S. Frosh. (2005). “Jung and the Nazis: Some Implications for Psychoanalysis.” Psychoanalysis and History, 7(2), (253–271), 257.

[11] N. R. Goldenberg, “Reply to Barbara Chesser’s Comment on “A Feminist Critique of Jung” Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 3: 3 (1978), 724.

[12] Adams, M. V. (1997). “Jung and Racism.” Self & Society, 25(1), 19–23.

[13] Ibid.

[14] J. Collins. (2009). “SHADOW SELVES.” Interventions, 11(1), 69–80.

[15] Ibid.

[i]. As anti-Semitism increased during the Weimar period, Jewish-owned liberal newspapers began to suffer economic hardship because of public hostility to the ethnic composition of the editorial boards and staffs (Mosse 1987, 371). The response of Hans Lachman-Mosse was to “depoliticize” his newspapers by firing large numbers of Jewish editors and correspondents. Eksteins (1975, 229) suggests that the response was an attempt to deflect right-wing categorizations of his newspapers as part of the Judenpresse.

Comments are closed.