Balzac and the Jews

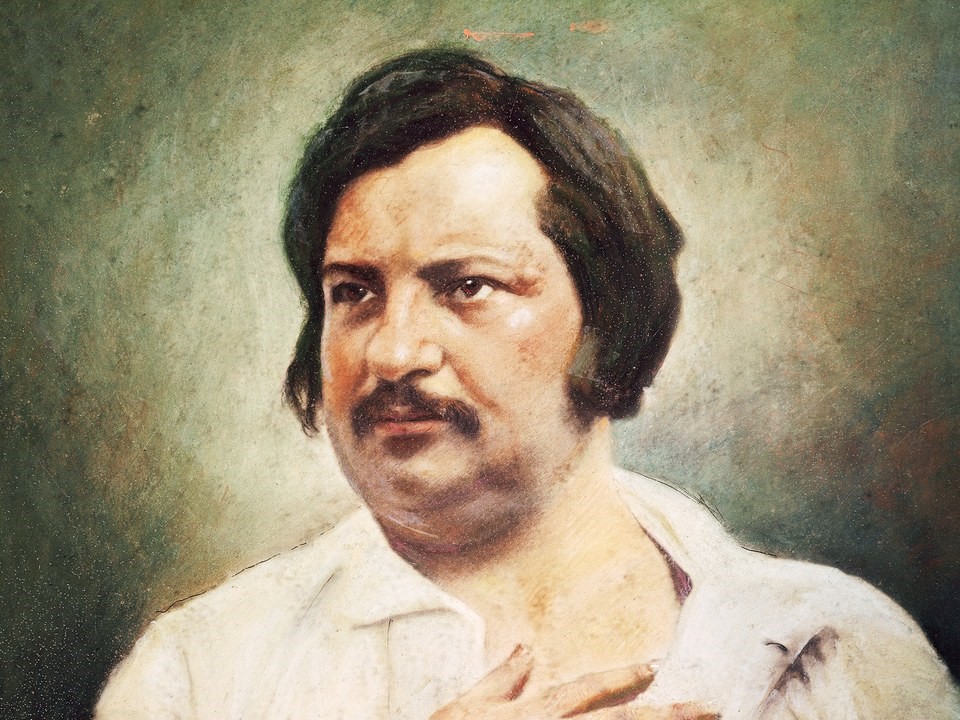

Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850) was an incredibly prolific French novelist of the first half of the nineteenth century. A pioneer of realism, he wrote 85 novels in twenty years, many comprising parts of his multifaceted examination of French society, which, invoking Dante, he dubbed La Comédie Humaine—The Human Comedy. Through carefully observing every social actor, profession, institution, and condition of French life, Balzac aimed to analyze the forces underlying the economic and social changes wrought by an emerging capitalist society—a society he believed was excessively motivated by money at the expense of traditional values.

His most famous works include Eugenie Grandet (1833), Pere Goriot (1934), Lost Illusions (1837), and Cousin Bette (1846). In developing the novels that would comprise La Comédie Humaine, Balzac hit upon the (then revolutionary) idea of using recurring characters. He wrote with great attention to detail to depict and explain their lives, and strived to present them as real people with real triumphs and frequent failures. Never fully good nor fully evil — his characters are entirely human in their desires and their behaviors. Balzac’s attention to detail and unfiltered depiction of people in society had never been seen before in literary writing. In addition to his remarkable powers of observation and prodigious memory, he had an intuitive understanding of people and their motivations which, borrowing the term from Sir Walter Scott, he called “second sight.” The French poet Baudelaire, an ardent admirer of Balzac, noted how “All his characters are endowed with the same vital flame which was burning within himself.”[1]

After working for three years as a lawyer’s apprentice, the young Balzac turned his back on the profession, finding it inhumane and tedious in its working schedule. His experiences in the law did, however, provide the basis for many plotlines in his novels which often center on legal disputes, wills and contested legacies. Turning his attention to writing, his early attempts to forge a literary career proved unsuccessful, as did later attempts to achieve success as a publisher, printer, businessman, critic, and politician. Despite experiencing dire poverty and constant rejection, Balzac continued to write, and his breakthrough came with The Chouans (1829), a novel set in the aftermath of the French Revolution. Its success encouraged him to devote himself wholeheartedly to a literary career. From this point, his life’s purpose was to achieve glory as the historian of his time, as the “secretary” of French society. In this endeavor he developed what many would regard as insane work habits.

Balzac’s energy was unbounded and his productivity astounding. His phenomenal work ethic was necessitated by a penchant for luxurious living—a tendency that constantly plunged him into debt, and led to his being hounded by creditors for most of his adult life. To evade them, he registered under pseudonyms and frequently changed his lodgings. While Balzac eventually earned decent money from his literature, his reckless spending always ensnared him in further debts: bills exist for his order of fifty-eight pairs of gloves at one time, and for similarly extravagant purchases from his fashionable tailor and jeweler in Paris. Balzac was famous for his bejeweled walking sticks, red leather upholstered library, busts of Napoleon (whom he loved), and other things of a luxurious and superfluous nature. In a letter from 1828, his publisher and friend Latouche wrote:

You haven’t changed at all. You pick out the [expensive] rue Cassini to live in and you are never there. Your heart clings to carpets, mahogany chests, sumptuously bound books, superfluous clothes and copper engravings. You chase through the whole of Paris in search of candelabra that will never shed their light on you, and yet you haven’t even got a few sous in your pockets that would enable you to visit a sick friend. Selling yourself to a carpet-maker for two years! You deserve to be put in Charenton lunatic asylum.[2]

It’s more than a little remarkable, then, to discover that, amid this obsessive pursuit of luxury goods, and a long-term romance with (and ultimate marriage to) a Polish countess, Balzac found time to write for sixteen hours per day. He wrote slowly, but toiled with incredible focus and dedication. He described in 1833 his relentless writing routine:

I go to bed at six or seven in the evening, like the chickens; I’m awaken at one o’clock in the morning, and I work until eight; at eight I sleep again for an hour and a half; then I take a little something, a cup of black coffee, and go back into my harness until four. I receive guests, I take a bath, and I go out, and after dinner I go to bed. I’ll have to lead this life for some months, not to let myself be snowed under by my debts. The days melt in my hands like ice in the sun. … I’m not living, I’m wearing myself out in a horrible fashion—but whether I die of work or something else, it’s all the same. … I am driven by the terrible demon of work, seeking words out of the silence, ideas out of the night.[3]

While Balzac’s feverish method of composition didn’t always allow for meticulous attention to the niceties of style and finish, he often made innumerable corrections and revisions to the proof sheets of each novel. He dressed for the task in a monkish white robe encircled by a golden belt from which hung a pair of scissors and a penknife. Usually occupied with writing several novels at the same time, he always felt compelled to press on, not only due to the urgency of ever-mounting debts, but to give birth to the unique conception of the world seething in his brain. In this endeavour, he kept an incredible level of focus and commitment to his craft: at one point he wrote for a stretch of 48 hours with only three hours of sleep for the entire duration.

His nocturnal working schedule necessitated a reliance on black coffee that has become the stuff of legend. Balzac, who called coffee “the great power of my life,” reputedly drank between 50 to 300 cups a day to stay fuelled and focused on his work, describing its effects thus: “Coffee falls into the stomach … ideas begin to move, things remembered arrive at full gallop … the shafts of wit start up like sharp-shooters, similes arise, the paper is covered with ink.”[4] His extreme work habits and coffee consumption likely contributed to his death from congestive heart failure in 1851 at the age of 52.

Balzac and the Jews

Balzac’s novels offer entertaining and sharply-observed chronicles of all facets of French society from 1789 to 1848— from the Revolution through the First French Empire of Napoleon I, the Bourbon Restoration, the July Monarchy under Louis Phillipe, to the Second Republic. This era coincided with the entrance of Jews into mainstream society in Western Europe. Indeed, Balzac can be credited with being the first novelist to make Jews and non-Jews live together in the same world.

Jews overwhelmingly supported the French Revolution of 1789 which promised them civic and economic equality. They were officially “emancipated” by a proclamation of the National Constituent Assembly in 1791—the legal culmination of the moral universalism of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Notwithstanding the proclamation, many leading Enlightenment thinkers, including Voltaire, Kant, d’Holbach and Diderot, regarded Jews as exploitative and enmeshed in medieval superstition and chauvinistic, immoral, exploitative behavior. While Voltaire opposed the Inquisition’s targeting of Jews, he noted in his Philosophical Dictionary that: “You will find in the Jews an ignorant, lazy, barbarous people who for a long time have combined the most undignified stinginess with the most profound hatred for all the people who tolerate them and enrich them.”[5] Kant observed that Jews were “a nation of usurers … outwitting people amongst whom they find shelter. … They let the slogan ‘let the buyer beware’ their highest principle in dealing with us.”[6]

Until the proclamation of 1791 most French Jews lived in ghettos segregated from surrounding societies. The rights granted to Jews in France were later extended to Jews throughout much of Western Europe—Germany, Italy and the Netherlands—by conquering Napoleonic armies, and then by the revolutions that swept through Europe between 1830 and 1848. After 1830, all careers were opened to Jews in France, and they entered fully into mainstream society. France’s Jewish population was, however, comparatively small: only one-tenth that of Germany and one-fiftieth that of Austria-Hungary. In the Pale of Settlement, Jews were about one hundred times more numerous in relation to the native population than they were in France where the Jewish population had only reached 75,000 by the end of the nineteenth century.[7] Despite this, as Jewish migration to Paris increased, people were increasingly confronted with the social and economic effects of unfettered Semitism, and Jews came to constitute an important new element of the society Balzac set out to describe.

In his sociological outlook, Balzac, a political reactionary, saw parallels between human society and the animal kingdom (Old Man Goriot is dedicated to a zoologist, Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire). Like all species, the various types of human animal have a common origin, but they evolve and diversify according to their environment. The leafy calm of the French provinces is the natural habitat of Balzac’s virtuous Rastignac family. The city of Paris, where most Jews resided, was, on the other hand, “like a forest in the New World,” infested with “savage tribes, where rapacious individuals, unchecked by religion or monarchy[; they] thrive at the expense of the weak.” Humans, of course, are more sophisticated than beasts: “In the animal kingdom, there are few dramas and little confusion; animals simply attack one another. Humans attack one another too, but the intelligence that they possess to varying degrees makes the struggle more complex.”[8] Balzac both loved and hated Paris as the hub of the French world, and his novels set there offer a terrible picture of human ruthlessness.

About thirty Jewish characters inhabit the pages of La Comédie Humaine, with a few reappearing in several novels. Despite comprising an important new part of French society in the domains of the arts and sciences, the theater, and especially the world of finance, Balzac’s Jewish characters remain ethnically distinct. Rashkin claims that Balzac’s unsparing portrayal of Jews (none of whom are given French names), and his implicit emphasis on “openly converted Jews” and “unseen, infiltrating Jews,” is evidence of his being “haunted by France’s trauma of Jewish assimilation.”[9] Balzac always stresses the uniqueness of Jews, portraying Jewishness as a strong and troubling trait. Conversion and assimilation in no way erase Jewish identity which, for Balzac, was fundamentally ethnic.

Jewish physical and Psychological Characteristics

Balzac’s Jewish characters don’t always identify themselves as Jewish, though their origins are immediately apparent to non-Jews through physiognomy or scent or aura. One non-Jewish character in Cousin Pons (1847), Rémonencq, is said to possess close-set eyes that revealed “a Jew’s slyness and concentrated greed,” though in his case, “the false humility that masks the Hebrew’s unfathomed contempt for the Gentile was lacking.” Another Jewish character, Moses Halpersohn, a refugee Polish Jewish physician possesses a nose that is “Hebraic, long and curved like a Damascus blade.” Halpersohn’s stereotypically Jewish physiognomy reflects his stereotypically Jewish character: specializing in the treatment of nervous disorders, he becomes rich through charging exorbitant prices for his services—a practice reflecting “his scorn for his patients and society in general. … Medicine becomes a game of high finance, a means to acquire gold and power.”[10]

Balzac’s depiction of Jewish women reflects, by contrast, “an orientalist fantasy” characteristic of the romantic literature of the time. Balzac’s Jewesses, who are mostly confined to the (often overlapping) roles of actress and prostitute, exude mystery, charm and exoticism, possessing a beauty beyond the conventional that evokes the biblical atmosphere of The Song of Songs. In Scenes from a Courtesan’s Life (1838–47), Balzac contends that Jewish women, “though so often deteriorated by their contact with other nations,” often exhibit a “sublime type of Asiatic beauty,” and “When they are not repulsively hideous, they present the splendid characteristics of Armenian beauty.” Such a description applies to Jewish art dealer Elie Magus’ daughter Noemi, “a Jewess as beautiful as a Jewess can be when the Semitic type reappears in its purity and nobility in a daughter of Israel.” The actress Coralie is likewise portrayed as “a Jewess of the sublime type” who, notwithstanding her physical appeal, retains “all the native Hebrew instinct for gold and jewels — for the golden calf.”

Balzac’s (often attractive) Jewesses differ not only physically from their male co-ethnics, but also morally in their capacity for loyalty and generosity. At the same time, their exotic sexuality exerts over their non-Jewish lovers a “paralyzing fascination that constitutes an obvious analogue to the dominance enjoyed by Jewish men in the world of finance.”[11] For Balzac, an inability to detect Jewish physical features and exercise requisite caution condemns “a poor fellow of twenty-seven” who “had the innocence of a lad of sixteen” to be ripped off by the art dealer Magus. A more vigilant and experienced man would, Balzac contends, “have noticed the diabolical look on Elie’s face and seen the twitching of the hairs of his beard, the irony of his moustache, and the movement of his shoulders which betrayed the satisfaction of Walter Scott’s Jew in swindling a Christian.”

Balzac’s character Elias Magus as depicted by artist Charles Huard (1874-1965)

Magus is Balzac’s exemplification of a type he grew to know exceedingly well due to his passion for collecting art and antiquities—the Jewish trader who, through sharp business practices and ethnic networking, becomes immensely wealthy:

The name of Elias Magus is too well-known in the Human Comedy to need introducing. He had retired from trading in pictures and objets d’art and, as dealer, had adopted the procedure that Pons had followed as a collector. The celebrated valuers—the late Henry, Messieurs Pigeot and Moret, Thoret, Georges and Roehn, in fact, the experts of the Louvre Museum—were as babes compared with Elias Magus, who could pick out a masterpiece from under the grime of centuries, who knew every school and the signature of every painter. This Jew, who had come to Paris from Bordeaux, had given up business in 1835 without giving up his squalid appearance: that he maintained, in accordance with the habits of most Jews, so faithful to its traditions does this race remain. In the Middle Ages, persecution forced the Jews to disarm suspicion by going about in rags, perpetually complaining, whining and pleading poverty. What was once a necessity has become, as is always the case, an ingrained racial instinct, an endemic vice. By dint of buying and selling diamonds, dealing in pictures and lace, rare curios and enamels, delicate carvings and antique jewelry, Elias Magus had come to enjoy an immense untold fortune, which he had acquired through this kind of commerce, nowadays so important.[12]

Jews who, like Magus, feign poverty while being secretly rich make repeated appearances in Balzac’s novels. In The Initiate (1848), one character is surprised at the luxury of a room in a poor section of Paris, “but his surprise only lasted for an instant, for he had seen among German and Russian Jews many instances of the same contrast between apparent misery and hoarded wealth.” Balzac’s wealthy Jews live frugally, and the moneylender Gobseck even denies ownership of a gold coin he drops to maintain the illusion of poverty. Jewish women, on the other hand, enjoy opulent luxury In Balzac’s world. As courtesans and actresses, they live in houses furnished by the men who keep them. The more beautiful the Jewess, the richer the dwelling she demands.

Jewish ethnic networking, swindling and avarice

Magus uses Jewish ethnic networks to assiduously track every masterwork in Europe: “Magus had his own map of Europe with every masterpiece marked on it, and at every relevant spot he had co-religionists who kept their eyes open on his behalf in return for a commission—but the reward was meagre for the amount of vigilance entailed!” Balzac likens the monomania of Magus to the desires of kings: Magus is proud of his power to buy the finest canvases which he hoards in his mansion, thus depriving the gentile community of its great works of art.

In Cousin Pons (1847), Magus is given the opportunity to plunder the art collection of Sylvain Pons, an elderly professor of music, who has carefully accumulated precious artworks over his lifetime. Tricking Pons’ landlord into selling him four of the professor’s masterpieces while their owner lays stricken on his deathbed, Balzac informs us that, when confronted by such a magnificent collection, “Admiration, or, to be more accurate, delirious joy, had wrought such havoc in the Jew’s brain, that it had actually unsettled his habitual greed, and he fell headlong into enthusiasm, as you see.” The Jewish dealer, however, quickly regains his composure: “’On an average,’ said the grimy old Jew, ‘everything here is worth a thousand francs.’ ‘Seventeen hundred thousand francs!’ exclaimed Fraisier in bewilderment. ‘Not to me,’ Magus answered promptly, and his eyes grew dull. ‘I would not give more than a hundred thousand francs myself for the collection. You cannot tell how long you may keep a thing on hand. … There are masterpieces that wait ten years for a buyer, and meanwhile the purchase money is doubled by compound interest. Still, I should pay cash.’”

The ability of Jewish merchants to swindle their naïve non-Jewish interlocutors is a recurrent theme in Balzac’s novels. In Eugenie Grandet, for example, Eugenie’s skinflint father is taught a valuable lesson by a cunning Jewish dealer:

Some years earlier, in spite of his shrewdness, he had been taken in by an Israelite, who in the course of the discussion held his hand behind his ear to catch sounds, and mangled his meaning so thoroughly in trying to utter his words that Grandet fell victim to his humanity and was compelled to prompt the wily Jew with the words and ideas he seemed to seek, to complete the arguments of the said Jew, to say what that the cursed Jew ought to have said for himself; in short to be the Jew instead of being Grandet. When the cooper came out of this curious encounter he had concluded the only bargain of which in the course of a long commercial life he ever had occasion to complain. But if he lost at the time pecuniarily, he gained morally a valuable lesson; later he gathered its fruits. Indeed, the good man ended by blessing that Jew for having taught him the art of irritating his commercial antagonist and leading him to forget his own thoughts in his impatience to suggest those over which his tormentor was stuttering.[13]

Avarice, lust for power and contempt for gentiles are psychological traits Balzac frequently ascribes to his Jewish characters, and they often serve as paradigms for the analysis of non-Jewish characters who manifest similar traits. One non-Jewish character is said to be as “eager for gain as a Polish Jew,” while in Lost Illusions the luckless and penniless poet, Lucian Chardon, is advised that, in order to succeed in Paris, he needs to become as “grasping and mean as a Jew; all that the Jew does for money, you must do for power.”

This characterization of the Jewish mindset persisted in French literature through to the late nineteenth century. In Guy de Maupassant’s Bel Ami (1885), for example, two young journalists discuss their boss, a Jewish newspaper proprietor, in the following terms:

They went into a café and ordered iced drinks. Saint-Potin started to talk. He talked about everybody and about the paper with a profusion of surprising detail. “The boss? A real Jew. And you know, you’ll never change the Jews. What a race!” And he quoted amazing examples of their avarice, the peculiar avarice of the sons of Israel, the efforts they would make to save ten centimes, their haggling, their barefaced way of asking for discounts and getting them, their whole moneylending, pawnbroking attitude. “And yet with all that, a good sort, who doesn’t believe in anything and diddles everybody. His paper, which is semi-official, Catholic, liberal, republican, ‘Orleanist,’ custard pie and sixpenny ha’penny, was only founded to help him play the stock market and back up his other ventures. He’s very good at that and he earns millions by means of companies that haven’t got tuppence worth of capital. … And the old skinflint talks like someone out of Balzac.”[14]

In the 2012 film version of Bel Ami, the Jewish identity of this newspaper owner was totally erased from the story.

While the Jew is placed by Balzac at the margins of French society, he remains at the center of the forces generating destructive social change. This particularly applies to his Jewish characters connected to the world of finance. Such characters include the Keller brothers, the moneylender Gobseck, and the financier Nucingen. In Gobseck (1830–35), Balzac depicts “a usurer sitting like a spider at the center of his web and asserting his power over the ‘socialites’ and ne’er-do-wells who come to him for loans.”[15] Gobseck is a man who uses gold to exert influence and to control the destinies of others, and is “Balzac’s model of the successful Jew whose extraordinary self-discipline enables him to pursue his quest for gold, despite obstacles.”[16]

The cover art of one edition of Gobseck

As the self-appointed historian of French social life in the first half of the nineteenth century, Balzac was acutely conscious of the immense and steadily growing significance of money. “God of the Jews, thou art supreme!” he quotes Racine. Through usury, he notes, “Jews have monopolized the gold of the world, that all powerful invention due to the Jewish intellect of the Middle Ages, which after six centuries still controls monarchs and peoples.” In a letter to his sister in 1849 from the Ukraine, an exasperated Balzac declared “You have no idea of the avidity of the Jews here. Shylock is a mere rogue, an innocent. Remember, this is merely in the matter of exchange; loans are sometimes fifty per cent even between Jew and Jew!”[17] In the world of Balzac’s novels, a “good Jew” is one “who only charged us fifteen per cent for the money we borrowed.”[18] The Jewish propensity for usury is regarded by Balzac as a hardwired ethnic trait stretching back to the ancient world, where even “In the days of Moses there was stock-jobbing in the desert!” In the Balzacian novel, gold is invariably the emblem of the Jew, symbolizing the tribe’s rapacity and wealth.

In The Rise and Fall of Cesar Birotteau (1837) Balzac presents the life story of a manufacturer of cosmetics who “becomes a prey to a group of blood-sucking bankers and speculators,” while in his 1843 novella The Imaginary Mistress, he tells the story of Polish Count Adam Laginski, “one of the great Polish lords who let themselves be preyed on by the Jews,”[19] Symbolizing the close historical relationship forged between Jews and European aristocratic elites against the interests of the native peasantry, the Count of Roche-Corbon in The Venial Sin (1832) pressures his Jews “only now and then, and when they were glutted with usury and wealth. He let them gather their spoil as the bees do honey, saying that they were the best of tax-gatherers. And never did he despoil them save for the profit and use of the churchmen, the king, the province, or himself.”

Balzac modelled his Jewish financier, Nucingen, who appears in more of his novels than any other character, on Baron James Meyer de Rothschild, whom he knew personally. Balzac told his future wife in 1844 that James, “the high baron of financial feudalism,” was “Nucingen to the last detail and worse.”[20] Nucingen is Balzac’s personification of Jewish money power and the social and political corruption attendant on the misuse of that power. In Splendors and Sorrows of Courtesans (1838–47), Balzac, with Nucingen (and thus Baron James) in mind, declared that “all rapidly accumulated wealth is either the result of luck or discovery, or the result of legalized theft.”[21] Nucingen is “the wiliest of all the rogues in The Human Comedy: a banker who can engineer a liquidation of his own assets, or plan an investment portfolio on a client’s behalf, simply and solely to further his own ends—enriching himself but bankrupting others by what is tantamount to legalized crime.”[22]

Balzac’s character Nucingen (as modelled on Baron Mayer de Rothschild)

The Rothschilds: Balzacian exemplars of Jewish money power

Balzac is the likely originator of the claim that the Rothschilds made their fortune through obtaining advance news of Napoleon’s defeat at Waterloo—using this information to make a huge profit on the Stock Exchange. The story is incorporated into the plot of The House of Nucingen (1838), where he describes the Jewish financier’s second greatest business coup as resulting from a massive speculation on the Battle of Waterloo. The twentieth-century Jewish American banker, Bernard Baruch, claimed it was this story that “inspired him to make his first million.”[23] While the scale of the Rothschilds’ return on this speculation has been exaggerated over the years, the Third Baron Victor Rothschild confirmed the basic accuracy of the story, and economic historian Niall Ferguson contends that Napoleon’s return from Elba on March 1, 1815, can be regarded as “an immense stroke of luck for the Rothschilds” with Bonaparte plunging Europe back into war and thus “restoring the financial conditions in which the Rothschilds had hitherto thrived.”[24]

The idea of a large speculative profit made from advanced news of a military outcome shocked many of Balzac’s contemporaries: “indeed, it epitomized the kind of ‘immoral’ and ‘unhealthy’ economic activity that both conservatives and radicals disliked when they contemplated the stock exchange.” To patriotic Frenchmen, the Waterloo speculation symbolized the greed, cynicism and rootless cosmopolitanism of the Rothschilds. In his book Jews: Kings of our Time (1846), the socialist writer Georges Dairnvaell maintained that: “The Rothschilds have only ever gained from our disasters; when France has won, the Rothschilds have lost,” and noted that Baron James is “the Jew Rothschild, king of the world, because today the whole world is Jewish.” The very name Rothschild, he declared, “stands for a whole race—it is the symbol of a power which extends its arms over the entirety of Europe.”[25] For Dairnvaell’s political mentor, Pierre Proudhon, Jewish financiers like the Rothschilds were “always fraudulent and parasitical.”[26]

The Rothschilds extended huge loans to Austria, Prussia and Bourbon France after 1815. Kings and ministers throughout Europe could obtain all the cash they needed on demand, letting the Rothschilds handle the details as to where it came from, and how it would be repaid. This enabled the Rothschilds to exercise extraordinary leverage over governments. In Paris, James de Rothschild successfully lobbied King Louis-Phillipe, to whom he had constant access, to dismiss the government of Jacques Laffitte, because he disliked the latter’s foreign policy. When, in 1830, Charles X was toppled from the French throne, the fact that Baron James, his Court Jew, survived unscathed only confirmed for many the existence of an unassailable Jewish oligarchy.

James Meyer de Rothschild’s ability to secure from the French government the rail concession to link Paris and Belgium also incensed observers on both sides of French politics. In his 1846 book The Jews, Kings of the Epoch: A History of Financial Feudalism, Alphonse Toussenel criticized the terms under which the concession was granted. Believing the French rail network should be owned and managed by the state, Toussenel argued that France had been “sold to the Jews” and particularly to “Baron Rothschild, the King of Finance, a Jew ennobled by a very Christian King. … Thus does high finance dominate everything; Jewish interests are visible all about us.”[27]

Niall Ferguson contends that, in addition to pecuniary self-interest, “the Rothschilds saw their financial power as a means to advance the interests of their fellow Jews.” To poorer Jews throughout Europe, Nathan Rothschild’s extraordinary rise to riches had “an almost mythical significance” and his wealth “was intended for a higher purpose: ‘to avenge the wrongs of Israel’ by securing ‘the reestablishment of Judah’s kingdom—the rebuilding of thy towers, Oh Jerusalem!’ and ‘the restoration of Judea to our ancient race.’”[28] The Rothschilds were to play a critical role in the Zionist project. Indeed, Walter Rothschild, the 2nd Baron Rothschild, was the personal addressee of the 1917 Balfour Declaration which committed the British government to establishing a Jewish state in Palestine. Baron Edmond James de Rothschild funded the first Jewish settlement in Palestine at Rishon-LeZion, buying from the Turks large parts of the land that now comprises Israel. In 1924 he established the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association which acquired an additional 125,000 acres of land.

Conclusion

Grodzinsky contends that, while his Jewish characters “display common stereotypes of evil and avarice, Balzac was not a facile anti-Semite.” His portrayal of Jews in his novels is accurate to the extent that, in the French society of his day, disproportionate numbers of Jewish men were usurers and Jewish women were courtesans or actresses. Therefore, for Balzac “to create a community where Jews abounded in every profession would have been to create a world alien to the French reader. Balzac’s portrayal of the Jews reflects both his reality and literary tradition.”[29]

While Balzac, following his customary practice, paints each of his Jewish characters as a unique personality, they remain representative of Jews in general and fundamentally separate from mainstream French society. Thus, while Balzac, with characters like Gobseck and Nucingen, “takes the Jewish money monster and creates a real human being, this person is still an outcast.”[30] Moreover, Balzac’s male Jewish characters are invariably “unpleasant people, characterized by avarice, shrewdness and lack of conscience.”[31] The Balzacian Jew also exhibits fierce willpower, and is a protean figure who rapidly adapts and changes to advance his interests. In this endeavor, he, unlike many of Balzac’s French characters, effectively uses his intellect to override his emotions.

Balzac, in his quest for realism, lets some of his Jewish characters succeed despite their misanthropic personalities and practices. Lehrmann notes that Balzac “does not like the Jews but he admires them; he notes without pity their vices and idiosyncrasies, but he acknowledges a certain genius thanks to which they rise above the vulgarity of their profession and social condition.”[32] Balzac acknowledged the power of gold to cut across social barriers and to buy power and status, and despite his “frank hostility towards the Jews,” remained fascinated by a group whose “despised greed and cunning resulted in admired wealth.”[33] Balzac didn’t scorn the social and monetary rewards of success, and his years of struggling to establish a literary career only sharpened his understanding of the power of money—and of the ethnic group inseparably linked with that power.

[1] Honoré de Balzac, Cousin Pons (London: Penguin, 1978), 11.

[2] Quoted: in Daniel J. Boortstin, The Creators: A History of Heroes of the Imagination (New York: Random House, 1992), 359.

[3] Ibid., 358.

[4] Frederick Lawton, Balzac (London: Wessels & Bissell Co, 1910), 129.

[5] Voltaire quoted in: Hyam Maccoby, Antisemitism and Modernity: Innovation and Continuity (London: Routledge, 2006) 55.

[6] Immanuel Kant quoted in: Paul Lawrence Rose, Wagner, Race & Revolution (New Haven CT: Yale University Press, 1992), 7.

[7] Albert S. Lindemann, Esau’s tears: Modern Anti-Semitism and the Rise of the Jews (Cambridge UK: Cambridge University Press, 2000), 208.

[8] Graham Robb in Introduction to: Balzac, Old Man Goriot (London Penguin, 1972), vi-vii.

[9] Esther Raskin, Unspeakable Secrets and the Psychoanalysis of Culture (New York: SUNY Press, 2009), 133.

[10] Frances Schlamowitz Grodzinsky, The Golden Scapegoat: Portrait of the Jew in the Novels of Balzac (New York: Whitson, 1989), 48.

[11] Susan Rosa,”Balzac,” In: Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1

Ed. by Richard S. Levy (Chicago: ABC-CLIO, 2005), 54.

[12] Balzac, Cousin Pons, 141.

[13] Honoré de Balzac, Eugenie Grandet (London: Penguin, 2004), 115.

[14] Guy de Maupassant, Bel Ami (London, Penguin, 1975), 64.

[15] Balzac, Cousin Pons, 10.

[16] Grodzinsky, The Golden Scapegoat, 18.

[17] The Correspondence of Honoré de Balzac with a Memoir by his Sister Madame de Surville, Vol. 2 (London: Richard Bentley & Son, 1878), 345.

[18] Balzac, Cousin Pons, 123.

[19] Ibid., 10.

[20] Niall Ferguson, The House of Rothschild: Money’s Prophets 1798-1848 (London: Penguin, 1999), 351.

[21] Ferguson, The House of Rothschild,15.

[22] Balzac, Cousin Pons,

[23] Ferguson, The House of Rothschild, 15.

[24] Ibid., 96.

[25] Herbert R. Lottman, Return of the Rothschilds: The Great Banking Dynasty Through Two Turbulent Centuries (I.B. Tauris & Co Ltd, 1995), 269.

[26] Ibid., 31.

[27] Lottman, Return of the Rothschilds, 31.

[28] Ferguson, The House of Rothschild, 21.

[29] Grodzinsky, The Golden Scapegoat, 1.

[30] Ibid., 32.

[31] Ibid., 17.

[32] Ibid., 12.

[33] Ibid., 1.

Excellent article!

Very engaging read. Thank you.

Sounds like Balzac was primarily a victim of his own intemperance.

“Balzac’s male Jewish characters are invariably “unpleasant people, characterized by avarice, shrewdness and lack of conscience.”[31] ”

and

“Avarice, lust for power and contempt for gentiles are psychological traits Balzac frequently ascribes to his Jewish characters”

The current attitude that is very strictly enforced in the media and mainstream books is to dismiss all negative portrayals of Jews such as the above, as ‘unfounded stereotypes’. Therefore, in this context, we have to be tolerant of those who accept this narrative (‘unfounded stereotypes’), including many ‘right-wing’ people who support Israel. The mistake that many on the ‘Jewish-aware-right’ make, in my opinion, is to condemn the ‘Jewish-unaware-right’ and to condemn them so strongly that half the time they accuse them of being Zionists, and by this they mean they not only support Israel in the Israel-Palestine conflict, they suggest that they must secretly supporting all the Jewish aims, including undermining the West.

In fact these who cry Zionist! all the time at others on the right, they are only achieving one thing – they antagonise those on the right who were actually on the path to becoming Jew-aware, and as they antagonise them, they drive them off the path to becoming Jew-aware, and sometimes into the arms of the Jews who then befriend them. I refer to campaigners such as Tommy Robinson in England, although he is not ‘in their arms’ as he left Rebel media.

The Jewish-aware-right thought that a good way to persuade T Robinson to come round to their way of thinking was to threaten his mother with violence. The outcome? He wore a tee shirt with ‘Zionist’ on just to antagonise them, and they got super-triggered and are now convinced that T Robinson is secretly working for Mossad.

Shouting ‘ZIonist!’ and pointing the finger at those on the right who do not share all your views is not going to convert anyone to your cause, and in my view is the single greatest factor in ensuring continued support for Israel from the right. In my own case it made me, as a right-wing person, one of the supporters of Israel for many years. I dismissed the critics of the Jews due to so many of them coming across as abusive people and conspiracy theorists. I still think this is a characteristic of many of them who go too far and think the Jews have more power than they actually do. For example, if the Jews control the TV media, how is it that there is no TV documentary that sides with Israel and how is it they all side with Palestine?

The events that changed my mind into seeing that Jews were actually hostile to the West were two things – interacting with Jews on Breitbart, and reading a single comment once that mentioned Kevin MacDonald, then looking him up. This is why the academic approach and reasoned approach is much more fruitful than the other approach taken by many, which is to see anyone on the right who is not fully on board as some sort of enemy working for the Jews.

——————–

“Tricking Pons’ landlord into selling him four of the professor’s masterpieces while their owner lays stricken on his deathbed,”

See the details above in the article about this fictional event and the way the Jew tricked the landlord.

Suppose this was rewritten in such a way that there was no mention of the trickster being Jewish. Then suppose that you show this story in an experiment to see what the readers’ reactions are. In my opinion some people would respond with admiration and respect for the trickster, and others would be repelled by his dishonesty. I wonder if different races would respond differently? The reason I mention this was when I related a story of how I was cheated by Jews on Breitbart, I was surprised by how many Jews admired the Jew for cheating me and one said ‘that is how he got rich’.

Our problem is the information monopoly.

Once smashed, we are free.

This includes government schools, and taxpayer subsidized “private” schools.

The information monopoly has been temporarily suspended in the sense that for the last 30 years (and for how much longer?) people can read anything online about the Jews, but the only condition is that it is in a non-mainstream site by non-mainstream authors, as anyone mainstream who is involved in questioning the Jews will have their career ended.

But the information is there, it just does not have ‘mainstream approval’ and is never in mainstream, therefore it can easily get dismissed even if people become aware of what we are saying. This is why academic sites like this one are so useful in guiding the open-minded person, who will be converted by facts and arguments, but not by short statements on Twitter about Jews.

Another factor in our favour is the decreased trust in the MSM version of events, partly due to Trump calling the media ‘fake news’and partly due to distrust in the mainstream views on Global Warming and LGBT and diversity.

This breaking of the information monopoly (in the non-mainstream part of the internet) is what made me aware of what is going on, based just on a single comment in a Breitbart blog once that just said ‘Kevin MacDonald gets it’ and I looked him up. Without that lead I would probably still believe that Israel was an ally of the West & the 6 million was a historical fact.

The left & the Jews must know the effects of limited free speech are bad for their plans for the West (devastating for their plans in the long run), and yet they have not managed to stop limited internet free speech so far.

Basically there is a great mass of people in the middle and the left are trying to put them back to sleep and the right are trying to waken them up. Can enough waken in time before the censorship of the internet goes to the next level?

“The Jewish-aware-right thought that a good way to persuade T Robinson to come round to their way of thinking was to threaten his mother with violence.”

Though your point’s well taken and I agree with it overall, the above example involving Robinson was so obviously contrived. He was a Zionist long before that incident and videos have emerged proving it.

No. That incident was just more bad Jewish Supremacist choreography. Like the Lee Harvey Oswald assassination. Though, obviously, on a much smaller scale, it follows the template.

The fact is, Jews are demanding three things.

1. To be placed above criticism.

2. Loved unconditionally.

3. Blindly obeyed.

These are insane demands. Literally. I know the word gets tossed around a lot. But in this case it’s entirely accurate.

Insane because of its disconnect with reality and its disregard of the consequences.

The only way Jewish Supremacy can succeed is by coercion, intimidation, denigration and force.

But force is ultimately destablizing. It’s self-defeating for those who depend on it. And it’s extremely disruptive to economic activity. Which is definitely something they care about deeply. Proof their chutzpah has blinded the to reality. Which they generally hold in contempt.

This is why culture was created in the first place, to circumnavigate the use of force.

But Jews are so pathologically self-absorbed that they can’t see that their success depends on the nothing less than the destruction of culture.

Nation-wreckers? Worse, they Culture Destroyers.

And since culture is essential to the human enterprise, they’re the destroyers of humanity par excellence.

They have a long history of projecting their defects onto a scapegoat. Which explains why they call Whites “the cancer of the human race” when it is they who are the cancer – obviously!

TOO’s on a culture role lately with KM’s recent post of Wagner’s music, the recent series on Friedrich The Great (nice coincidence as it was posted at a time when I’m rereading Carlyle’s great work on him) and now Balzac. Great content!

For all of the advanced men of that century (it’s worth remembering that there were always very few of them) the sweetest bone to gnaw on was a fact. And it’s this that makes our thinkers of the 19th century the most original. Their drive toward reality. For he could see the symbolic act not as a bit of hocus pocus, but as a tool with which to deal with the real world.

This relates nicely to Sanderson’s article.

Freudians have said that Balzac’s novels were so concerned with money because Balzac was anally regressive, that money for Balzac was a symbol of feces. In other words, Balzac was a neurotic.

Who thinks like that?

Of course, that’s a rhetorical quesiton round there here parts.

Anyway, for the Freudians, Balzac’s concern with money in his novels was a symbolic of his sick failure to grasp reality.

But, looked at from the point of view of our cultural greats, such as Wagner, Carlyle, and Balzac himself, the FACT is that, according to ALL accounts the 19th century, which saw the dramatic rise of Jewish power, created the modern money economy, and did both at the same time.

If we take Jewish commentators in general and Freudians in particular seriously, admittedly not an easy thing to do, we can say that Balzac’s insight enabled him to grasp a reality then that they still can’t face now!

Obviously, Balzac saw their obsession with money as something that would seriously damage society. Who alive today could possibly deny that he was right?

He very well may have been neurotic in some areas of his life. Who isn’t? But what wasn’t ever neurotic about him was his social perception. On the contrary, his social comprehension was luminous. And that’s why he’s one of our cultural heroes.

In any event, in their anxiety to criticize and invalidate our cultural heroes Jewish intellectuals rarely read very carefully. They didn’t then and they aren’t now. At least they’re consistent.

“Freudians have said that Balzac’s novels were so concerned with money because Balzac was anally regressive,”

The modern Jews are clearly turning on Balzac in modern times, and we can see why they are angry, as if there is one thing they cannot stand it is accurate stereotyping, but he must have also upset the Jews in the eary 1800s by portraying them as swindlers. However, notice that back then they could not ruin his career. Their power to silence critics really took off after WWII when ‘racism’ suddenly appeared as a tool to control what we can say, but back then they did not have this stick.

Maybe it will not be long before all books with Jewish stereotypes or black or arab or any racial stereotypes somewhere within the book are banned.

“Maybe it will not be long before all books with Jewish stereotypes or black or arab or any racial stereotypes somewhere within the book are banned.”

Exactly! To repeat what I’ve said before, most recently in response to another one of your comments,

Jews are demanding three things (for them and their Proxies).

1. To be placed above criticism.

2. Loved unconditionally.

3. Blindly obeyed.

But because they want this for their proxies – as proxies, not as partners, ever – they’re biting off more than they can chew, manage and control.

I’ve said it before and I’ll say it again, because it’s worth repeating. Though Jews are unquestionably good at infiltration, subversion and destruction, they’re no damned good at social-management.

Just look around you. Everywhere we look today we see collapse. Especially in tne capital of Jewish Supremacy, New York City.

Why? Because nothing fails like Jewish success.

That doesn’t mean we should ignore them or not fight back. But we definitely need to stop looking at them as some kind of unstoppable force or some sort of Boogeyman we’ll never escape from.

@ pterodactyl:

Sorry, Tommy Robinson doesn’t explicitly support native Britons and is an avowed “anti-racist”. Whether or not he’s still directly funded by Rebel Media, his anti-Muslim platform neatly coincides with the Zionist one.

Tommy Robinson is genuinely ‘not racist’ as you say in different words, but he is wakening many and putting them on the right path (of self-interest and patriotism), and we must not be fussy if people help our cause without completely agreeing with the whole message. T Robinson’s ‘lack of racism’ is what enables him to get as far as he does spreading a patriotic message, and making people realise that reducing immigration and being patriotic are good things. If he was the slightest bit racist himself, he would remain unknown and would be utterly condemned by other white people, as most white people only want ‘non-racist’ leaders and politicians for now. (In fact at his rallies you rarely see a black person or non-white).

Wolf Age on Red Ice is pretty good at explaining what I am trying to say.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MjAYoJRVA20

A good strategy to win over gentile Israel-lovers is to educate them on the USS Liberty attack and subsequent cover-up.

– and educate people on the way the Jews promote mass immigration of the 3rd world to the West, and the way they influence US foreign policy – any discussions about Russian interference in elections is a very good opportunity to point out Israeli interference.

Most right-wing people support the Jews as they see them as persecuted civilised people in Israel surrounded by a hostile primitive enemy, and so it is a good tactic with these people to demonstrate that Jews are doing their best to bring a hostile primitive 3rd world to the US and to all of the West, whilst not wanting them in Israel itself. This is the way to get through to these right wing types – they feel very strongly about mass immigration and will not take kindly to any group that promotes it when they find out.

Tommy Robinson hasn’t lost the support of Israeli Jews. On the contrary:

https://twitter.com/i/web/status/1137314733135212544

So ((they)) have befriended TR – this does not mean that deep down he shares their aims of destruction of the West, all it means is that they have shown friendship and support, and he has responded, without realising that they have done so to stop him being Jew-critical (also the purpose of Breitbart to stop the right from talking about Jews by controlling the narrative on their site). So why should he realise what the Jew’s hidden agenda is? (deception is their main skill) – meanwhile guess how the far-right have treated TR – they threatened his mother with violence!

The Right are their own worst enemy as their idea of public relations is abuse and hostility. This is how they keep their numbers so small. Instead of studying ‘How to Win Friends and Influence People’, they study ‘How to lose friends and alienate all those who could easily be your allies. Lesson 1: Go on Youtube, Twitter etc & call anyone a Zionist who does not fully agree with you. When others see that you think everyone works for Mossad they will dismiss you as a conspiracy theorist. Lesson 2: Swear a lot and don’t listen and be very offensive and aggressive. Instead of converting the undecided with genuine debate, insult them and drive them away.’