The Tory Parliamentary Struggle to Preserve English National Identity, 1753–1858, Part III

Part III: The Jewish Campaign Against Parliamentary Anti-Judaism, 1829–1836

The movement for Jewish “emancipation” in nineteenth-century England was spearheaded by Jews and their Whig or Liberal allies, while the opposition was led by the High Tories:

The High Tory majority in the House of Lords had acted as a barrier to the advancement of Jewish ‘emancipation’ … and some of the arguments put forward against the Jews, both in and out of Parliament, reflected the traditional Tory view that Church and State were part of an inseparable entity, in the promotion of which Jews ought to play no part. (Alderman, 2015)

In practice, Anglo-Jewry had more freedoms than their compatriots in central Europe, but in late-Georgian England, the laws on the books indicated that they were less free. Cecil Roth writes:

The entire body of medieval legislation which reduced the Jew to the position of a yellow-badged pariah, without rights and without security other than by the goodwill of the sovereign, remained on the statute book, though remembered only by antiquarians. As late as 1818 it was possible to maintain in the courts Lord Coke’s doctrine that the Jews were in law perpetual enemies, ‘for between them, as with the devils, whose subjects they are, and the Christian there can be no peace.’[1]

Despite his freedoms vis-à-vis Ashkenazim of Central Europe, in the English society of the nineteenth century, politically and professionally, the Jew was still excluded from the mainstream:

Public life was, in law, entirely barred. Jews were excluded from any office under the Crown, any part in civic government, or any employment however modest in connexion with the administration of justice or even education, by the Test and Corporation Acts. … These made it obligatory on all persons seeking such appointment to take the Sacrament in accordance with the rites of the Church of England. … Naturally these disqualifications included the right to membership of Parliament, for which the statutory oaths in the statutory form were a necessary preliminary. For the same reason the universities were closed, and, as a consequence of this, various professions.[2]

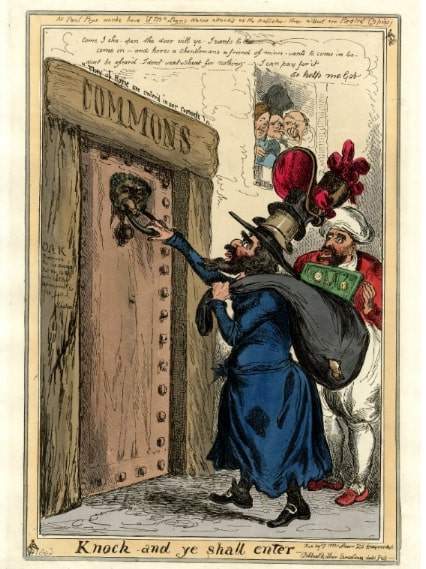

The Jew says: “Come I sha—Open the door vill ye—I vants to come in—and heres a shentlemans a friend of mines—vants to come in too—dont be afeard—I dont vant a sheat for nothing—I can pay for it So help me Got.”

Tory opposition to Jewish participation in English life was not irrational, but based on the incompatible ethnico-religious differences that separated both groups. From 1829 to 1858, resistance to Jewish infiltration was driven by two main reasons:

(a) Jewish foreignness, such as their Hebrew religious beliefs and Semitic race; (b) the danger Jews posed to the British economy and constitution. The latter ranged from Jewish commercial immorality to potential Jewish takeover and domination of the country to the destruction of the Christian church in England. The legal doctrines of Sir Edward Coke and Sir Matthew Hale were frequently invoked as justification for the continuance of Jewish civil and legal disabilities.

The High Tories shared a common philosophy of Jewish exclusion. This was eloquently articulated by the erudite Thomas Arnold, a “Broad Churchman” and headmaster of the elite Rugby School. Despite his Whiggish beliefs in “improvement” and latitudinarian rejection of dogmatic orthodoxy, he was a High Tory in his politics.

Arnold detested the “low Jacobinical notion of citizenship” of the Jewish Relief Bills, which “a man acquires a right to … by the accident of his being littered inter quatuor maria [lit. between the four seas, i.e. on land], or because he pays taxes.” Jews were barred from English citizenship because “citizenship was derived from race” and “distinctions of race … implied real differences often of the most important kind, religious and moral.” He continued: “Different races have different νόμιμα [customs], and … an indiscriminate mixture breeds a perfect colluvio omnium rerum [literally, a cesspool of all things].”[3] Race took precedence over culture, which is why Jews, an alien race, would always remain foreigners in England. Mixing races, like Jews and Englishmen, would lead to violence, as was the case in the ancient world. In this regard, Arnold wholeheartedly agreed with Aristotle:

Another cause of revolution is difference of races which do not at once acquire a common spirit; for a state is not the growth of a day, any more than it grows out of a multitude brought together by accident. Hence the reception of strangers in colonies, either at the time of their foundation or afterwards, has generally produced revolution.[4]

As a solution to the Jewish question in England, Arnold suggested that Jews be rounded up and deported:

The Jews are strangers in England, and have no more claim to legislate for it, than a lodger has to share with the landlord in the management of his house. If we had brought them here by violence, and then kept them in an inferior condition, they would have just cause to complain though even then I think we might lawfully deal with them on the Liberia system, and remove them to a land where they might live by themselves independent for England is the land of Englishmen, not of Jews.[5]

If the Jews had to face civil and legal disabilities in England, it was because they had brought these troubles on themselves.

As in 1753, it was the Jews who initiated the agitation for greater civil and legal equality, implying a less well-defined English ethnic identity for indigenous Anglo-Saxons. This began in 1829, when a petition for Jewish relief from civil and legal disabilities was drawn up by the Board of Deputies of British Jews. The Board selected the Jewish banker Nathan Rothschild to ask Prime Minister Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, to present the petition before Parliament. When handed the petition, the Duke suggested that he postpone it.

Despite an apparent willingness to consider Jewish relief at some future date, the Duke was no obsequious Judeophile. He was a “stern, unbending and uncompromising opponent of Jewish emancipation.”[6] This may have been shaped by Wellington’s personal belief that Jews were a race of devils:

Wellington told Harriet Arbuthnot that they believed the French to be devils as well as Jews: Once he had a Guerilla come to him, who told him he had had to guard three French officers from one post to another & that, in crossing a bridge, he thought the best thing he could do was to upset them into the river. This he did, carriage & all, ‘& do you know,’ he said, ‘they were all Jews for, as they were drowning, I saw their tails’![7]

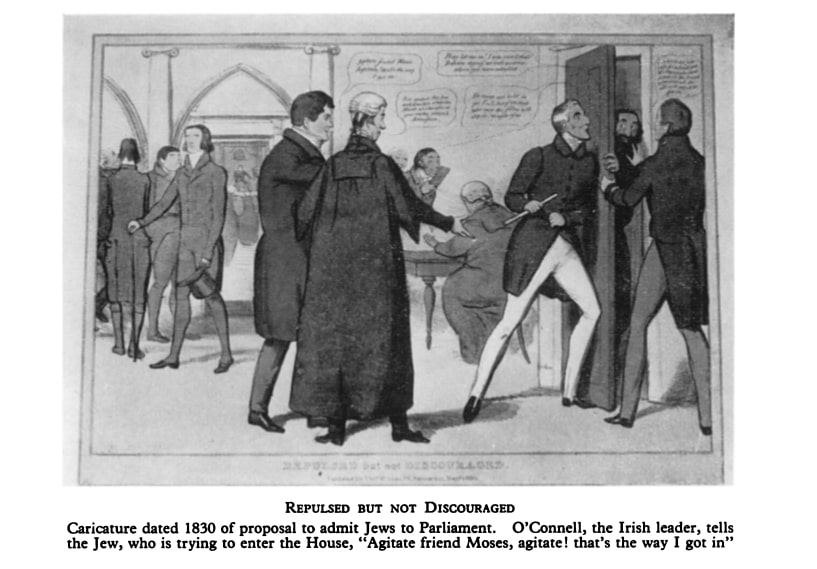

The Board of Deputies heeded Wellesley’s advice and in the following year, managed to convince the philo-Semitic MP Robert Grant to introduce a Jewish relief bill in the Commons. As an evangelical Christian, he believed his duty was to relieve the Jews of all civil and political disabilities because this would lead to mass conversion of the Jews to Christianity. Grant’s bill passed the first reading, but without a significant majority of the house. The High Tory Sir Robert Inglis urged the house to reject Grant’s calls for Jewish “emancipation.” For Inglis, Jewish relief was impossible because the Jews:

“were aliens, not in the technical and legal sense, when Lord Coke called them ‘aliens and perpetual enemies’ but in the popular sense of the word: they were aliens because their country and their interests were not merely different, but hostile to our own.”

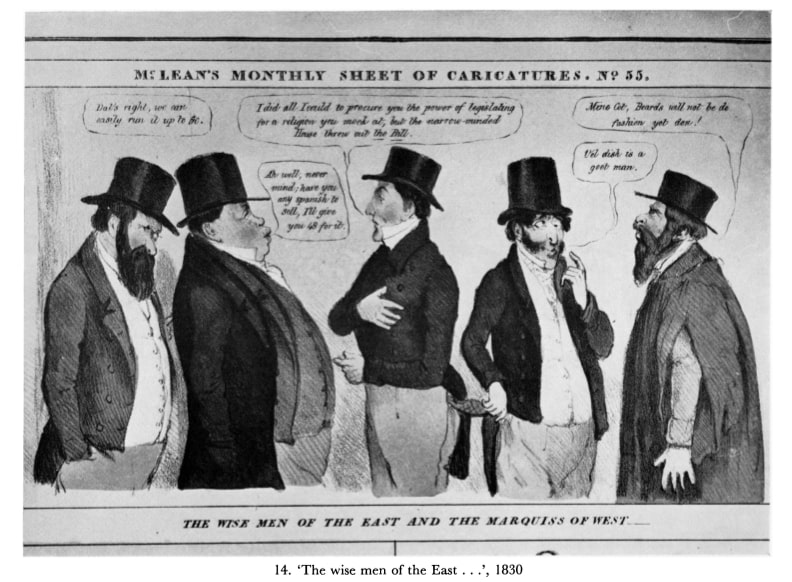

Philo-Semitic MP Robert Grant is saying to Rothschild: “I did all I could to procure you the power of legislating for a religion you mock at, but the narrow-minded House threw out the Bill.” Rothschild replies: “Ah well, never mind; have you any Spanish to Sell, I’ll give you 48 for it.” A Jew behind Rothschild whispers in his ear: “Dat’s right, we can easily run it up to 50.” Another Jew exclaims: “Mine Cot, beards will not be de fashion yet, den!” A satire on the abortive Jewish Emancipation Bill of 1830.

Racial identity among Jews was believed to be so strong that a Jew in London would have more in common with a Jew in Vienna than a Christian in his own country. If Jewish ethnic identity transcended national boundaries, then allowing Jews to sit in parliament would enable them to pursue “their own selfish and unnational” interests, to the detriment of the English majority. The Jews are a minority, but numbers are deceiving; even a small minority can make up for “its want of weight by its activity, and produce the greatest public events.”[8] Through bribery, Inglis said, Jews would buy up seats in Parliament and exercise a level of power and influence far out of proportion to their percentage of the population.

Jewish overrepresentation in commerce has been a fact of life since the Middle Ages; using their vast wealth and influence, Jews were able to manipulate entire governments to do their bidding, as if they were puppeteers pulling the strings of dumb marionettes, like the officials of the Pelham ministry. Since Jewish “emancipation” in 1858, Jews continue to exert disproportionate economic and political influence. During the second reading of the bill, the High Tory General Isaac Gascoyne asked the Commons rhetorically: “if the Jews had the power to grant the Protestants what they now asked from them, what would they have obtained?” He answered: “The history of the Jews at all times showed that they were not very tolerant to those opposed to them in religious opinions.”[9] If Jews had not shown tolerance toward others, why should the English nation show tolerance to Jews by granting them the same rights and liberties as Englishmen? The old General concluded with an appeal to the Commons to reject the measure. After he spoke, Lord Belgrave voiced his objections to Jewish relief on the grounds of both Jewish foreignness and undesirability of Jewish assimilation:

First, they were a distinct nation; secondly, they were … through the medium of their religion, disqualified for political privileges. Jews were scattered over almost all the countries of Europe and of the East, but they were amalgamated with the people of none. It was impossible then … that a Jew could ever be considered an Englishman, or love our native land as … an Englishman was wont to do.[10]

Since the British Constitution was maintained through patriotic feeling and the Jew “could never feel himself bound up in the fortunes of a country in which he only considered himself a sojourner,” admitting him to parliamentary office and granting him the elective franchise would be “deleterious.”[11] The bill was soundly defeated by a large majority of MPs. The Jews and their Whig allies had underestimated the strength of the Tory opposition.

Wellington’s ministry gave way to Earl Grey’s Whig ministry in 1830. The passage of the Great Reform Act in 1832 seemed to herald an age of more liberal progressive legislation and consequently, a sharp decrease in Tory influence and numbers. Jews and Pro-Jewish agitators returned to the struggle for Jewish “emancipation” with great fanaticism. In 1833, Grant tabled a motion for the house to resolve itself into a committee to investigate the so-called civil and legal disabilities faced by Jews. The Tory MP Robert Inglis objected, stressing the absurdity of Grant’s proposition that “religious opinions should not disqualify their professors from the holding of political power.” If this were true, then

the Parsee, the Brahmin, the Mussulman, the Jew, and all other sectaries and religionists” would have the same rights as native Anglo-Saxons by virtue of birth on English soil. The principle of religious tolerance, taken to its logical conclusion, would require placing “in the custody of very incompetent and unworthy men all the dearest interests of this country. And strangers they must continue to be—they must ever remain a distinct and separate nation; and was the Legislature—were the House of Commons—to unchristianise themselves and the country, in order to afford unnecessary privileges to these few persons? What right had a foreigner going into any country to find fault with the laws of that country, and pray their alteration in his favour, he being no more than a stranger and a sojourner? And strangers and sojourners the Jews must be until the restoration of their own Jerusalem—their ultimate home.[12]

Notwithstanding Inglis’s spirited rejection of the measure, it received far more Ayes than Noes. A committee was formed and a resolution passed in favor of Jewish “emancipation.” Grant then introduced a Jewish Civil Disabilities bill. During the bill’s second reading, Sir Oswald Mosley, grandfather of the same-named founder of the British Union of Fascists (BUF) in 1932, objected to the comparison of Jews to Roman Catholics, a favorite Whig stock argument:

The Roman Catholics, though many errors might have crept into their Church, were Christians, and … among them there were as many pious and conscientious communicants as belonged to any other Christian body or sect. Any concessions which had been made to the Roman Catholics afforded no precedent for putting upon the same par with them a class of men who blasphemed the sacred name of Jesus.[13]

This was met with cries of “No, no” from the Tories in the Commons. Nevertheless, the bill passed the second reading with a large majority. It also passed a third reading with another large majority, despite Tory objections that if Jewish civil disabilities were removed, Christianity would no longer be “a part and parcel of the law of the land” and Parliament would cease being a Christian legislature.

The bill was sent to the Lords, but was rejected after a second reading. The Lords affirmed Coke’s doctrine: “Christianity was part and parcel of the law of the land.” The Archbishop of Canterbury, William Howley said “the great principle of this State” is “that the religion of the country should be Christian.” The Duke of Gloucester said: “The English House of Peers was a Christian House, and ought never to consent to the admission into the Legislature of persons of anti-Christian tenets.” The Duke of Wellington, the great champion of the Anti-Jewish party, affirmed with the other Lords that “this was a Christian country and a Christian Legislature.” Like Sir Oswald Mosley, the Duke criticized the comparison usually made between Jews and Roman Catholics:

The Roman Catholic Relief Bill was adopted, because it was thought no longer necessary to continue the restrictions imposed by law on the professors of that religion, who had previously to their imposition, enjoyed all the privileges of which they had been deprived. The Catholics had a heavy ground of complaint on that head, whereas the Jews had no such complaint to make; they had never enjoyed privileges, and therefore could not claim their restoration. The condition of the Jews had, in fact, been much improved. They were formerly considered as aliens, and from the reign … of Edward the 1st, to the Commonwealth [i.e., the Cromwell regime, 1649–1660], their residence in this country was forbidden under severe penalties. The case of the Jews, therefore, stood on a very different footing from that of the Catholics and other Dissenters, to whom relief had been afforded.[14]

The bill was unceremoniously rejected in the Lords.

Grant re-introduced the petition in 1834, where it was approved by a majority and passed on to the House of Lords. During the second reading, the Earl of Malmesbury warned the Lords of the tremendous destructive power of the Jews:

Wherever they had obtained any footing, the result had been disastrous. No man who had travelled through Poland, where the Jews were in possession of nearly all the land, but must acknowledge that he had never seen a more wretched country. The Jews never laboured. They had in them no principle of bodily industry. They were never seen wielding the flail, or mounting the ladder with the hod. … If they admitted a Jew to a full participation of civil rights, why not admit a Mahometan, or a Chinese? Where were they to stop?[15]

The bill was rejected by a majority and then postponed for six months. It was again resurrected by the Commons in 1836, under Viscount Melbourne’s Whig ministry, but it was dropped before it could be voted on at a second reading.

The High Tories in the House of Lords were a significant obstacle to passage of the Jewish relief bills. They had emerged the victors in the struggle to preserve English national identity, at least during the 1830s.

As the intraparliamentary squabbling raged on, the Jews and their allies worked quietly in the background, removing the barriers to Jewish civic participation. These fell one-by-one like a row of dominoes until the barrier to parliamentary office became one of the few remaining. In this period, we see the first Jewish lawyer (1834), the first Jew to receive a hereditary peerage (1841), the first Jewish Lord Mayor of London (1855) and the first Jewish doctor (1856). Slowly the English acceded to pressure from Jews and liberals and acquiesced to their own ethnic suicide, an acquiescence that continues to this day.

[1] 1964, pg. 249

[2] Ibid, pg 249

[3] Stanley, 1858, Vol. 1, pg. 316

[4] http://classics.mit.edu/Aristotle/politics.5.five.html

[5] Stanley, 1858, Vol. 2, pg. 39

[6] https://www.thejc.com/news/uk-news/revealed-why-wellington-was-no-friend-of-the-jews-1.67186

[7] Hibbert, pg. 84

[8] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1830/apr/05/the-jews

[9] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1830/may/17/bill-for-removal-of-jewish-disabilities

[10] Ibid

[11] Ibid

[12] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1833/apr/17/emancipation-of-the-jews

[13] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1833/may/22/emancipation-of-the-jews

[14] https://hansard.parliament.uk/Lords/1833-08-01/debates/beb03756-a5b9-4037-a2d5-514399d630f9/EmancipationOfTheJews

[15] https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/lords/1834/jun/23/disabilities-of-the-jews

Relenting pressure and obviously a few bribes and blackmail behind the scenes with salami tactics.

Interestingly, this and the earlier part of this piece made no mention that anyone was alarmed that jews had freedom in banking and commercial bill trading. This is the kernel of their power to achieve their gradual takeover.

Thanks for the articles, fascinating reading about it.

Ah, democracy. Like fertilizer, except when it is in excess, as in being buried in it and having it shoved up your nostrils. Only a select few should be empowered to vote, carefully vetted, with unblemished records of the highest integrity and empirical grounding.