The Life and Times of Fay Stender, Radical Attorney for the Black Panthers, Part 1

Introduction

Fay Stender earned fame as a radical attorney in the 1960s and 1970s, defending two of the most prominent Black Panthers in highly publicized court cases. During the course of her career in left-wing activism, she embraced numerous “causes” with a passion as flamboyant as it was unbalanced. She worked strictly within the stream of Jewish anti-White activism, but inside that framework her aims were essentially random, a consequence of her peculiar personality. She displayed during the course of her work a toxic combination of Jewish radicalism, selfishness, ambition, egotism, and unrestrained female emotion. The blend eventually destabilized social institutions and got people killed.

Fay was the personification of psychological intensity, a classic marker of Jewish activism. Her personality traits were etched in bold lettering. People “who knew her intimately . . . regarded her as one of the most forceful persons they had ever met.”[i] Her sympathetic biographer mentions her “extraordinary” ego, and even her husband was appalled by her “analytic, calculating ambition.”[ii] She was “deeply typical” of the radical movement, says a fellow 1960s leftist, “the paradigmatic radical—relentlessly pushing at human limits; driven to a fine rage by perceived injustices; searching for personal authenticity in her revolutionary commitments.”[iii] Like many subversives of the 1960s, she was also a strongly identified Jew, and consciously linked the supposed values of her Jewish heritage with her social activism.

Her life story is a revealing case study in Jewish activism.

Early Life and Education

Fay Stender was born in San Francisco in 1932, into a middle-class Jewish family. Her grandparents hailed from the old country: Brest-Litovsk, Hungary, and Germany. Her father, Sam Abraham, was a chemical engineer; her mother, Ruby, was a teacher. They were a conventional family, not “political” or activist. Sam was Orthodox, but Fay and her only sibling, Lisie, were raised Reform, and they observed the Sabbath and other Jewish rites.[iv]

Fay began piano lessons at four years of age, and quickly showed real talent. By the time she entered her teen years she was on track to become a concert pianist. She earned the privilege of performing Beethoven’s Emperor Concerto with the San Francisco Symphony when she was just fourteen years old.

Not long afterward, she rebelled against her rigorous schedule. She wasn’t happy with her stunted social life (she was attending private school to maximize practice time); she demanded to be allowed to attend Berkeley High School with her friend Hilde Stern. She also wanted to reduce her practice time. Her parents submitted only after much argument. She did not fit in very well in high school, however, because Hilde’s circle of friends considered her arrogant. She was “a loner, restless and impatient with frivolity.”[v] She read much in her spare time and made the National Honor Society.

Fay and her family evinced a good deal of neurosis. Her mother was “controlling” and “tended toward hypochondria,” frequently dragging Fay around to doctors and imposing unnecessary therapies on her. Fay herself suffered periods of serious depression throughout her life, and may have suffered from bipolar disorder.[vi] She also enjoyed provoking authority. At public institutions, she would open doors marked “private” and, boldly entering, implicitly challenging the White social order.

At seventeen, Fay followed Hilde Stern to Portland, Oregon, to study English at Reed College. Reed had a reputation as left wing and iconoclastic. Fay reveled in her freedom from parental control, and began dating for the first time. She was, like many young people, almost painfully idealistic. A letter of advice to her younger sister featured this earnest impression: “The real meaning of life is in three things, love, beauty and pain. And these three are all really one which is God or Truth. And you will only come to know and understand this by giving, and giving too much.”[vii]

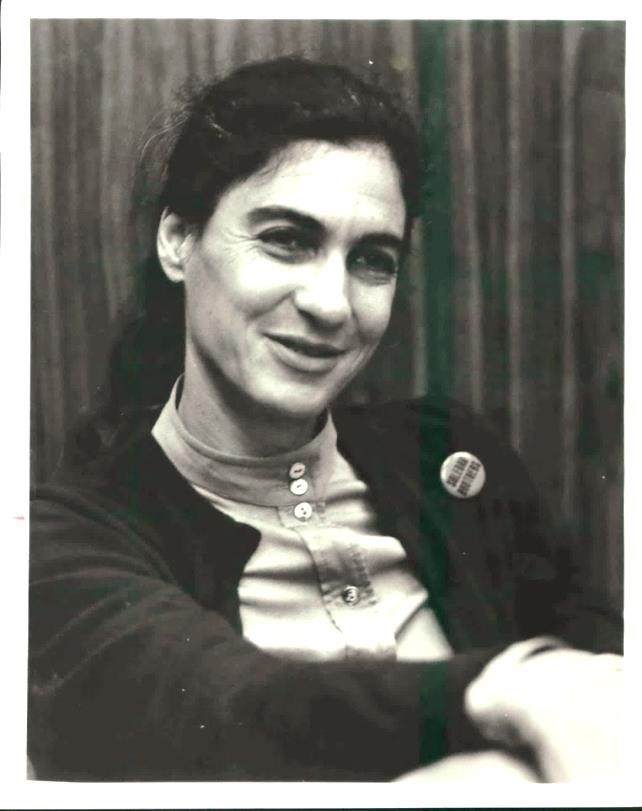

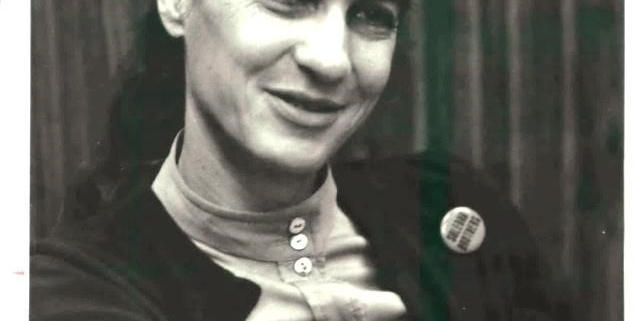

A young Fay Stender at Reed College

Jewish idealism does not frown upon unorthodox modes of sexual expression. Sex is also, of course, a well-known tool of revolutionaries. In her sophomore year she fell for a youthful professor, Stanley Moore, a womanizing Communist with a taste for bondage (Fay’s biographer Lise Pearlman describes the relationship as “sado-masochistic.”[viii]) Moore turned her strongly to the left and “convinced her to reject her cloistered upbringing and bourgeois Jewish values.”[ix] It began to dawn on Fay that “there was something wrong with this country, something I wanted to change.”[x] She quickly embraced radical ideas, a rare example of a Gentile converting a Jew to revolution.

In her junior year she transferred to the University of California at Berkeley. There she befriended a fellow student, Chinese immigrant Betty Lee, and, talking “a million miles a minute,” “passionately expounded on Communism, racism and imperialism.”[xi] Her knowledge of these issues must have been superficial, but her passion wasn’t. She was vocal enough with her new beliefs that the FBI opened a file on her and Betty as suspected Communists.[xii] The FBI would track Fay through much of her life.

Law School

At this point, Fay decided to become a lawyer; she felt the profession commanded influence. Her ambition fired, she took extra courses and graduated early (January 1953) with honors. She won a scholarship to the University of Chicago Law School, which was considered one of the best in the country at the time, at least by progressives. It was a center of “Legal Realism,” which was the idea “that the law was a flexible tool which balanced competing interests to accomplish particular public goals,” that is, liberal goals. The school had a large number of Jewish students and professors, in a city with the world’s third largest community of Jews.[xiii]

At this time very few women attended law school, and even fewer graduated. It was the almost universal belief within the profession that women lacked the emotional stability to become good trial lawyers; Stender’s career would provide tragic backing for that belief.

Fay entered the school that fall on the lookout for an outlet for activism. She was already alert to the plight of the “oppressed” and “disadvantaged.” She was aware that the school was surrounded by the Black ghetto of Chicago and gave visiting friends tours along its streets.[xiv] George Jackson, the Black convict with whom her fate later became entwined, was then a budding thug on those very streets.

In her first semester, Fay attended a meeting of the National Lawyers Guild (NLG). There she met the president of the student chapter, Marvin Stender, a third-year law student and native of Chicago. He was a tall, earnest, true-believing leftist. They quickly fell in love and married, a match described as “a relationship both saw as a joint venture on behalf of the oppressed.”[xv] Her parents were happy she finally settled upon—after many dalliances with Gentiles—a member of the tribe.

Fay and Marvin threw themselves into cauldron of leftist politics. Fay was “finding it increasingly difficult to suppress her disapproval of how the law aided the haves over the have nots.”[xvi] Fay assisted Professor Malcolm Sharp, president of the NLG, who was working on an appeal for Jewish atomic spy Morton Sobell. The NLG, a Communist front organization, would be the base of their activism throughout their lives. Marvin worked with Jewish Professor Hans Zeisel on a landmark study of trials and juries (The American Jury) that would have the effect of opening up juries to the machinations of identity politics, an opening that Fay later exploited, perverting justice and destabilizing institutions.[xvii] They both raised funds for the Rosenberg boys and worked on the electoral campaign of Congressman (and eventual judge and Bill Clinton presidential advisor) Abner Mikva.[xviii] Their activism was always aligned with the Jewish current.

The Stenders and their friends had closely followed the Rosenberg case, which had reached a jolting conclusion that summer of 1953. They watched the McCarthy hearings and cheered when in the spring of 1954 Army chief counsel Joseph Welch dramatically confronted Joseph McCarthy—“Have you no sense of decency, sir?”—in defense of a National Lawyers Guild member.[xix]

Early Career in Berkeley

In the summer of 1956, Fay obtained her law degree, finishing in the top third of her class. She prevailed upon Marvin to move to the Bay Area. There Fay got a position clerking for an elderly Gentile judge on the California Supreme Court, but was horrified to learn he supported anti-miscegenation laws. He was sexist too, so she quit. She and Marvin wanted to work for NLG stalwarts Barney Dreyfus and Charles Garry, the two most prominent Leftist lawyers on the West Coast, but they were facing subpoenas from the House Un-American Activities Committee at the time. They steered Fay to a Black lawyer, and she spent some time defending Black prostitutes, at least until her new boss was disbarred for perjury. Here she enlightened one dark corner of racist America: she “convinced judges to order the same lenient sentences as white prostitutes routinely received.” [xx] Are we to believe that the judges upholding the stern monolith of White supremacy saw the error of their ways merely because of the honeyed suasion of the young Jewish lawyer?

In September 1957, President Eisenhower sent the 101st Airborne Division to Little Rock, Arkansas, to enforce racial integration in the schools there. Fay would spend much of her career working in the civil rights movement.

In 1958, Fay gave birth to a son, Neal, and in early 1960, a girl, Oriane. She stayed home with them for three years even though “she could not keep up with the demands of motherhood and had no desire to manage a household.”[xxi] She was depressed; after all, she had a deeply racist and sexist society to set right. Worse, Marvin chose this time to begin an affair. Fay moved out of their house and rented an apartment. She still thought fondly of Stanley Moore—“obsession” is the word used by her biographer—and considered reuniting with him.[xxii]

Yet even as a full-time mother, Fay found time to agitate. Her new focus on children, as grudging it was, opened another part of American society to her gaze. Over the past century or so, activist Jews like Fay have relentlessly dragged every aspect of human society into the sphere of political agitation, usually with disastrous results. For a change, however, her work here had positive results. She advocated for natural home birth and breast-feeding, and successfully brought suit to change a California law that barred husbands from the delivery rooms of hospitals. She donated her time to help young mothers learn how to navigate the passage of childbirth, earning the devotion of a number of these women.

Working for Garry and Dreyfus

In 1961, Fay again asked Charles Garry for a job. This time he gave her a part-time position. Garry was Armenian; his main partner, Barney Dreyfus, was the product of an Irish-Jewish marriage. Both men were NLG members and former Communists. For decades they were at the center of most of the groundbreaking radical court cases in the Bay Area. Fay also gained entry to their social circle, particularly the group around leftist Jewish lawyer Bob Treuhaft and his wife Jessica Mitford, both also former Communists. (Most former Communists didn’t repudiate their ideology, needless to say, only the stifling party discipline.) The couple had connections galore, and “threw the best Leftist parties around.”[xxiii] A decade later, Fay and Jessica would work together on prison reform in California.

Fay joined the San Francisco branch of the NLG, of which Dreyfus was the long-time president. A couple years later he would take over the national organization, and place “civil rights” at the top of the agenda.[xxiv]

Fay mainly did research for the firm, filing motions or working on appeals; Garry did not consider her capable of trying cases in a courtroom. Her new bosses quickly learned that Fay would relentlessly pursue every possible angle to help win a case. She would identify herself totally with a case, even a minor one, as if it were a deeply important cause. Finally the firm allowed her and another lawyer to take charge of a case at trial, one they considered a loser. Fay promptly violated courtroom etiquette by challenging a routine police test, and waved her hands about “to underscore her arguments.” The judge was “unimpressed” and they lost.[xxv]

In 1963, still separated from Marvin (but not divorced), she re-connected with another lover from Reed, Bob Richter, for periodic nights together; this arrangement would last for eighteen years.[xxvi] She also saw a number of other men, including Stanley Moore. At the same time, she and Marvin enjoyed occasional pastimes together with the children.

Fay by this time reversed her earlier repudiation, however deep it may have been, of her Jewish heritage. She wanted her children to grow up Jewish. Every year her parents held a large family Passover Seder, and Fay usually attended. Now she brought her children too. Fay wanted them to “benefit from . . . the Torah’s ideals of justice and freedom.” (Ah yes, the Torah’s well-known ideals . . .)[xxvii]

Civil Rights Activism: Freedom Summer

By 1963, Marvin and Fay were following the burgeoning civil rights movement with growing excitement. They joined with others to form the East Bay Friends of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), which became a major fund-raiser for the national organization. The SNCC had grown out of the 1960 sit-in movement, meant to function as a student arm of the civil rights movement. Fay, Marvin and their (Jewish) friends held “hundreds” of fund-raising events over the next few years.[xxviii]

That fall, SNCC announced a summer campaign for 1964 to register Blacks to vote in Mississippi. SNCC chose Mississippi because it was the most militantly segregationist state.[xxix] The activists desired drama and clashes, and counted on shocking publicity like Bull Connor’s firehoses and dogs to help accomplish their agenda.[xxx] The effort was labelled “Freedom Summer.” Jews across the nation thrilled with excitement; an offensive against the most recalcitrant, racist White bastion was about to begin. (The Jewish liberal Allard Lowenstein shared responsibility for the idea.)[xxxi] Almost two-thirds of the approximately 900 White volunteers for Freedom Summer were Jewish.[xxxii] It was a movement closely aligned with radical Jewish sensibilities: a majority of the White volunteers “had parents affiliated with the Communist party and other Marxist organizations,” and the event “underscored SNCC’s declining religiosity and growing identification with sexual liberation and revolutionary communism.” [xxxiii] The original Christian pacifism of SNCC had rapidly turned into something quite different under the influence of its new “White” associates.

In early June 1964, Fay signed up to provide free legal help for the SNCC activists. She arrived in Jackson, Mississippi on August 10 for a short stint. Tensions in Mississippi were sky high when Fay arrived; the natives correctly regarded the coming of the Northern radicals as an invasion meant to break down their social structure; local papers often referred to “race-mixing invaders.”[xxxiv] Less than a week before, the corpses of civil rights activists Michael Schwerner, Andrew Goodman, and James Chaney had been discovered buried in an earthen dam only eighty miles away; angry locals had killed them.[xxxv] Schwerner and Goodman were—of course—New York Jews; Chaney was a Black Mississippian.

One aspect of Freedom Summer that still evokes very painful memories from many White participants is interracial strife, particularly concerning sex. This issue ties in with Fay Stender’s later career as prison reformer, as we will see. There was a great deal of sexual coercion on the part of Black men, who could be “persistent and aggressive,” with “scarcely veiled hostility.”[xxxvi] At the orientation of the White volunteers, a Black staff member had frankly warned of the possibility of rape: “The only way . . . a Negro man has been able to express his manhood is sexually and so you find a tremendous sexual aggressiveness . . . so, in a sense, what passes itself off as desire quite often . . . is probably a combination of hostility and resentment, because he resents what the society has done to him, and he wants to take it out on somebody who symbolizes the establishment . . .”[xxxvii] If a woman was strong enough to resist, “she generally became a focus for the hostility of the black men on the project.”[xxxviii]

By the end of Freedom Summer, Whites and Blacks had gotten a handle on each other—a strongly negative one. Blacks viewed whites—usually Jews—as “smug, superior, [and] condescending,” and Whites labelled Blacks with such terms as “slow,” “lazy,” or “bullshitting Negroes.”[xxxix] So much for the idea that interaction reduces bigotry.

Thus we see, according to Jewish author Debra Schultz, why it is “extremely difficult to talk about interracial sex in the southern civil rights movement.”[xl] The White women went through sexual hell, hard enough in itself to discuss, but they also didn’t want to air atrocious Black behavior, which would tend to discredit the movement. Very few of them were prepared to reconsider the basis of their activism, so silence was their only option. When Fay Stender finished working for Black rights, she didn’t want to talk about it, either.

[i] The main sources on the life of Fay Stender are David Horowitz and Peter Collier, “Requiem for a Radical” in Destructive Generation: Second Thoughts About the Sixties (New York, 1990), and Lise Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra: The Life and Times of Movement Lawyer Fay Stender (Berkeley, CA: Regent Press, 2018), and American Justice on Trial: People v. Newton (Berkeley: Regent Press, 2016). The quote is from Horowitz and Collier, “Requiem for a Radical,” 24.

[ii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 279; Horowitz and Collier, 28.

[iii] Horowitz and Collier, 22.

[iv] Pearlman covers Stender’s ancestry in Call Me Phaedra, 9-11.

[v] Horowitz and Collier, 25.

[vi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 11-12.

[vii] Ibid., 32.

[viii] Ibid., 91-2.

[ix] Ibid., 37, 40.

[x] Perry, Douglas. “Why Reedie and radical lawyer Fay Stender fought for prison reform — and paid with her life,” The Oregonian, June 27, 2015. Viewed September 14, 2017: http://www.oregonlive.com/living/index.ssf/2015/06/why_reedie_and_radical_lawyer.html

[xi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 37.

[xii] Ibid., 44. Betty went on to become a radical member of the Berkeley City Council.

[xiii] Ibid., 47, 49. Bernardine Dohrn of the Weathermen would later obtain a J.D. from this school.

[xiv] Horowitz and Collier, 26.

[xv] Ibid., 26.

[xvi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 69.

[xvii] Ibid., 68. Zeisel’s work “later played a key role in assuring a diverse and sympathetic jury for the Huey Newton murder trial.”

[xviii] Ibid., 68.

[xix] Ibid., 59.

[xx] Ibid., 74-7.

[xxi] Ibid., 80.

[xxii] Ibid., 81-2.

[xxiii] Ibid., 82-8. In 1971, Hilary Rodham would clerk for the former Communist Treuhaft.

[xxiv] Ibid., 96.

[xxv] Ibid., 90.

[xxvi] Ibid., 90-91.

[xxvii] Rabbi Yosef Ovadia, former Chief Rabbi of Israel and head of the Council of Torah Sages: “Goyim were born only to serve us. Without that, they have no place in the world . . .” See also Kevin MacDonald’s comments here.

[xxviii] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 95.

[xxix] Kenneth Heineman, Put Your Bodies Upon the Wheels: Student Revolt in the 1960s (Chicago: Ivan R. Dee, 2001), 36.

[xxx] Connor was the Chief of Police in Birmingham, Alabama, who used dogs and firehoses to break up civil rights demonstrations in May 1963. The resulting publicity produced widespread disgust and led to the first Civil Rights Act in July 1964.

[xxxi] Bruce Watson, Freedom Summer: The Savage Season of 1964 That Made Mississippi Burn and Made America a Democracy (New York: Penguin Books, 2010), 63.

[xxxii] Jonathan Kaufman, Broken Alliance: The Turbulent Times Between Blacks and Jews in America (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 98.

[xxxiii] Heineman, Put Your Bodies Upon the Wheels, 37, 39.

[xxxiv] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 97. Bruce Watson refers to Freedom Summer volunteers as “invaders” more than a dozen times.

[xxxv] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 97.

[xxxvi] Mary Aickin Rothschild, A Case of Black and White: Northern Volunteers and the Southern Freedom Summers, 1964-1965 (Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 1982), 138-39.

[xxxvii] Rothschild, A Case of Black and White, 138.

[xxxviii] Ibid, 139.

[xxxix] Bruce Watson, Freedom Summer, 267.

[xl] Debra Schultz, Going South: Jewish Women in the Civil Rights Movement (New York: New York University Press, 2001), 115.

Stender got what she deserved. That may sound harsh but what befell her was a direct result of what we see playing out every day in the US among the Left in the form of virtual signaling.

Nicely written, and largely convincing. I hate to carp, but it’s typical of all modern writing to completely suppress facts about Jewish money, notably that the Fed allows Jews to help themselves. You talk as though protest, activism, expensive study, travel, career change, campaigning, and all the rest are endogenous to these people and need no explanation. In fact they are expensive; most people can’t afford them however much they may want to. It’s a very serious gap.

Of course money is not only important but also vital for their undertakings. And not only vital, but obviously also abundant, as recently exhibited here by the uncountable organizations active in Maine.

Neither Nemmersdorf, nor any other writer here, should be expected to grope back to December 23, 1917, every time they reach for their pen.

Funding of thugs etc is essential to the way Jews operate. 1913 is more relevant than 1917. I don’t know if Nemmersdorf has any information on Jewish money sources; maybe not. But omission of it, and the related issues of newspaper, TV, film, academic, school etc biases, makes his articles shallow description, not helped by his failure to dig into stories from the same tribe of liars

Of course 1913 is more relevant than 1917, since the former made the latter possible: through the Jekyll Island conceived Fed., creating unlimited fiat currency, of which millions were funneled to the Bolsheviks through the German 4-D banks [ Dresdner-Dortmunder-Diskonto and Deutsche ]: this time around to thoroughly, and for ever after, take Christian Civilization off its hinges. Awaiting its final coup twelve months from now.

Clinton naturalized 230,000 grateful new citizens before his election: that will reoccur tenfold weeks before 2020.

But, what the hell, why should Nemmersdorf, or any other author waste his and our time by wasting untold pages on what is common knowledge anyway ?

Why don’t you write up fifty pages of what you deem absolutely essential, get it ready for paste and copy on your site, so anyone writing about music or the sex life of ants, can include it in their essays ?

At the end of the article, I see Nemmersdorf has not dealt with the impact of the US in Vietnam, which was Jew-driven; Jews knew this and had to control what little debate there was. Presumably Stender was part of the time-wasting/ sensational/ distraction. I’m afraid a big dose of skepticism is needed; for example it seems unlikely to me that Eldridge Cleaver would have got away with things he was credited with – but it made a good book. I’m also highly skeptical about Stender surviving five bullets from close range, and the rest of it. Her role may well have been to provide headlines for ‘news’. However, I do believe a commenter here who said she was very ugly.

Of course I meant Dec. 23, 1913 [ thirteen ], the passage of the Fed Reserve Act in Congress, by the quorum who did not need to be home for Christmas Eve.

Wow, what a story. What’s even more bizarre is the astonishing account of how Fay Stender ended up. Talk about white jewish radicalism gone haywire.

https://www.oregonlive.com/living/2015/06/why_reedie_and_radical_lawyer.html

I’m surprised I never heard of Fay Stendal. You’d think she’d still be a leftist celebrity. Might her legacy been purposefully kept quiet because it represents an embarrassing case study of the shadow side of the George Jackson case?

This was truly a wonderful article. Despite that anti-majorityite’s smarts it was Zyd networking, with other members of their us-against-them nationhood, that stands out for her anti-majority success. I’ve read about her kid all over the world, in various countries. Reading about her never-ending conflict against the values of her birth place, denotes that her life was full of turmoil. She reminds one of that Soviet Ambassador Alexandra Kollontay. She advocated free love and like the whore in this piece she copulated with an army of males. In all probability, Sender’s progeny will continue eliciting many of her traits within their Euro environments. sad.

Is there going to be more to this article in the future? Seems to lack a conclusion. Why did you write it? Should have been called ‘Book Report with Attitude.’

Frankly I find the article appalling. If Horowitz is your source– what makes you think he’s doing anything but bombing the hell out of the target? Also– you need to get a grip on your mind. How can you possibly know and judge another person’s life just based on your superior point of view? And you have failed to prove your point. Where is the evidence against her? You’ve simply assembled a set of pre-conclusions apparently based solely on your cultural attitudes. The pretentious contempt with which you treat the subject is absurd. You don’t really know anything about this person other than what you pretend to know. I also don’t know anything about this person but I’m starting to like her.

Do yourself a favor. Don’t write any more articles. Who can take this publication seriously when it prints smarmy justifications for outright murder 50 years after the fact?

I harbor serious doubt whether you will even deem Part 3 as your demanded Conclusion: as her serious resignation from everything but sex. What would happen to Literature, Philosophy or Historiography if no author were allowed beyond his own personally observed happenings ?

Be assured, the time has not yet arrived, to submit articles to you and/or your employers for approval.

The moderator banned me years ago, but I decided to reply to Issar. I’m familiar with Charles Garry prison law project and the rest of the Jewish commies operating in San Francisco and Oakland 1950-1990.

I don’t like David Horowitz either. But Tony knowledge every word in Fay Stender part 1 and 2 is absolutely right. I knew all these people and how they operated.

We in law Enforcement had a celebration when the Jew commie witch got what she deserved. Stender was really, really, really, ugly, something only a black man would touch.