The Life and Times of Fay Stender, Radical Attorney for the Black Panthers, Part 3

George Jackson and the Soledad Brothers

Meanwhile, Fay met George Jackson.

Huey Newton had told Fay about George Jackson and asked if she could help him. Jackson (whose family had relocated to California) was serving a life sentence in Soledad Prison for a $70 robbery, according to his sympathizers. The truth is a bit otherwise. He had committed a long string of muggings and burglaries, and the State of California finally wised up and sentenced the teenager to one year to life.[i] He could have gotten out in a year or two, if he had behaved. He didn’t. He and a buddy formed a prison gang, ran a gambling ring, sold drugs and alcohol, and pimped homosexual prisoners.[ii] He fought with guards and beat other prisoners. The prison administration considered him a violent sociopath. Consequently, his sentenced was continually extended, and he spent years in solitary with his cell door welded shut.[iii]

Jackson was intelligent and could express himself well. Like Cleaver, he read revolutionary literature—Marx, Lenin, Mao, Fanon—and wrote feverishly. He believed that America’s Blacks were a “colonized” people (an idea picked up by the Weathermen); that “the country’s institutions depended on their continued enslavement and subjugation; and that this state of affairs could only be reversed by an armed, violent revolution.”[iv] While his yearning for violent revolution was genuine, he would admit that Marxism was his “hustle.”[v] Jackson was a leader and a good organizer, and formed a group of dedicated followers.

In mid-January 1970, shortly before Newton told Fay about him, Jackson had murdered a White prison guard in cold blood. It was his response to the killing (by White prison guards) of three Blacks who were engaged in a prison-yard fight with Whites. Jackson and two others were charged with the murder and became famous—the subversive publicity machine roared into action—as the “Soledad Brothers.”

Fay visited Jackson in Soledad in early February. He spoke to her with feigned diffidence and her “heart melted.”[vi] She immediately felt a strong attraction to him, and decided to take on his case. She assembled a legal team, the Soledad Brothers Defense Committee, and worked almost round the clock. Some of her friends smiled at her insistence that this undertaking was (now) the most important cause in the world.

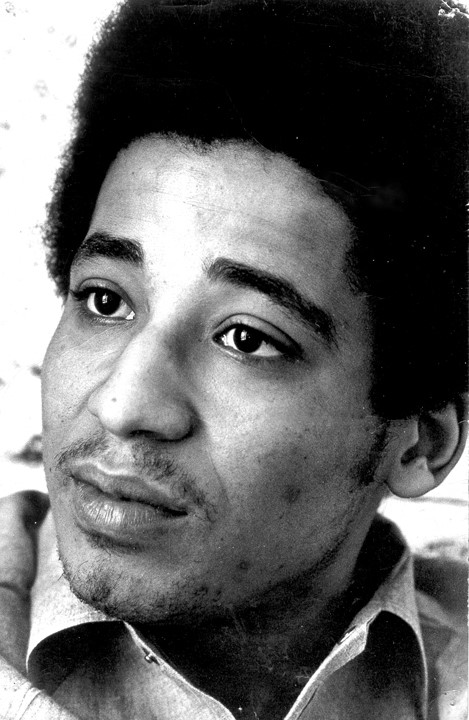

George Jackson

She issued a leaflet: “Three young Black inmates . . . may soon be murdered by the State of California . . . They are innocent. Their right to a fair trial is being systematically and intentionally destroyed by the prison administration . . . They will be railroaded to the gas chamber unless we move to stop this injustice.”[vii] It was a typical effusion from Stender: literally hysterical.

Fay interviewed many Soledad inmates in connection with the Jackson case. Few of them had knowledge of the murder but all of them had grievances to share. Fay believed every word they said, and conceived a major effort at prison reform. This reform was firmly connected in her mind with revolution. Fay was convinced the prisoners were “going to be in the vanguard of the social revolution.”[viii] She “embraced the need for social revolution [and] recognized people might die,” flippantly justifying it all: “People are dying all the time. The important thing is that they die in the right cause.”[ix] She would come to regret these sentiments, but not before blood was spilled.

Newton Freed and Fay Spurned

On May 29, 1970, the appellate court decision in the Newton case was unsealed; it was a totally unexpected reversal of conviction. The court ordered a new trial, and Newton was released on bail in August.[x] Fay, who was entirely responsible for the appeal, had sprung a murderer, and basked in the sort of fame that only subversives could value. At a party the night of his release, reveling Panthers declared that Newton needed a woman; they corralled Fay and escorted the two to a bedroom. Fay was ecstatic and later bragged about it to female colleagues, some of whom were appalled. Fay thought it meant that the Panthers viewed her as a real comrade, but Pearlman suggests that Newton simply regarded her as another woman he could use.[xi] In fact, it wasn’t long before he coldly snubbed her in public, and that was that. She had spent thousands of hours laboring joyfully for a psychopathic murderer, and garnered the natural reward.

Newton in the meantime lived the high life: he hobnobbed with lefty Hollywood celebs, snorted cocaine and hosted various beautiful women in his penthouse in downtown Oakland, paid for by Jewish movie producer Bert Schneider.[xii] In saving him from the electric chair, Fay would ensure that many other people would fall victim to Newton’s violence, including numerous murders that he committed personally or ordered his henchmen to carry out. Huey lingered on for years, a thug posing less and less plausibly as public benefactor, until a younger thug shot him down on the street in 1989.

Fay and Huey Newton at a press conference upon his release, August 5, 1970.

Working for George Jackson

Meanwhile Fay worked with her customary manic energy on Jackson’s case, seventy hours a week. She brought in a lead counsel, and planned to put “the system” on trial as in the Newton case. She couldn’t see that Jackson was using her as Newton had. She raised hundreds of thousands of dollars with speeches and appeals, and chaired fund-raising events featuring Jane Fonda and Dick Gregory. She was riding high on hectic activism and fame.

It was a time heavy with portents. The Black Panther Fred Hampton had been shot dead the previous December in what was portrayed as a police assassination; Charles Garry charged the police with genocide against the Panthers; the Weathermen went underground and began bombing shortly after; in early May 1970 the Kent State shootings claimed the lives of four students amid enormous antiwar demonstrations. It seemed to many as if the system was on the point of dissolution. The revolutionaries were living day to day in a state of acute excitement, and Fay was as giddy as any of them.

Fay began collecting and editing the letters Jackson had written in prison, hoping to duplicate the success Beverly Axelrod had had with Soul on Ice. Publication would generate funds for the defense, provide favorable publicity, and promote her career. Jackson had written at length about his violent revolutionary fantasies (waging guerrilla warfare, poisoning the water supply of Chicago, taking bloody revenge on the system, etc.), but Fay deleted the worst of it because she wanted to portray him as a sympathetic victim of racism.[xiii] She thought she could win at trial with that strategy, but he had no faith in that avenue and was intent on a prison breakout.

She took to visiting Jackson in a miniskirt and high boots. She thought she was perfectly fit to relate to prisoners: “our interaction is more flowing, more natural, because I’m a woman. It might also be because they know I regard them as brothers and believe in them.”[xiv] She believed in them, all right: she began having sex with Jackson in the semi-private visiting rooms that attorneys could use, and on one occasion prison guards dragged her out half disrobed.[xv] At other times, she would embrace Jackson libidinously in front of other (appalled) lawyers, letting him rub against her “for relief.”[xvi] She had also initiated a lesbian affair with a young female legal assistant.

Fay recruited volunteers to help with the Jackson case as well as with other prisoners—often young female volunteers. It became a dangerous mixture of ultra-violent felons, heady social activism, and hormones. Fay actually encouraged her volunteers to “comfort” the inmates any way they could, meaning sex.[xvii] And they did:

The inmates courted any woman who expressed interest in them. With few exceptions . . . the women responded like besotted rock star groupies. One guard confiscated a nude picture of a paralegal. Women legal assistants or attorneys . . . surprised the wardens when they used private conference rooms for trysts.[xviii]

Needless to say, Fay and her horny assistants earned the burning contempt and anger of the prison administration. Fostering the resentment of the inmates and encouraging their violent revolutionary fantasies made the California prisons a ferment of discontent. Correctional officers could see an explosion on the horizon.

The Break with Jackson

Fay’s partnership with Jackson would not last long. He had no desire to pose as a downtrodden victim in a courtroom and was planning a breakout. He had followers training for guerrilla warfare in the California hills, and planned to lead them personally in a war against America after making his escape. He thirsted for revenge against the White man. He began to demand that Fay and others smuggle weapons and explosives into the prison.[xix] Fay denied this request, but others hesitated.

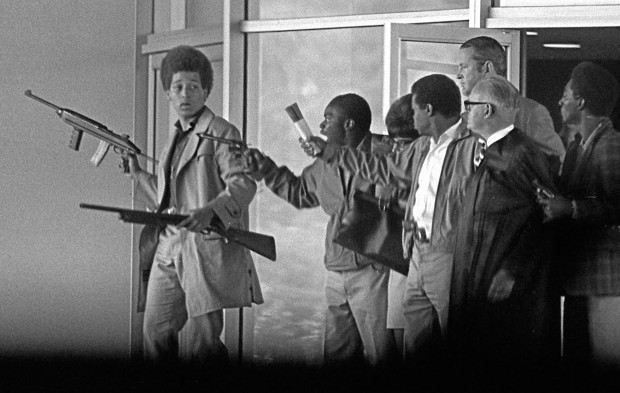

Jackson’s first attempt to escape was a spectacularly bloody failure. On 7 August 1970, Jackson’s seventeen-year-old brother Jonathan invaded the Marin County Courthouse armed with guns purchased by the notorious Communist Angela Davis, who had fallen in love with George and become involved in his defense. (The lovebirds had bonded over the prospect of killing White people; she gushed to him in a letter, “We have to learn to rejoice when pig’s blood is spilled.”[xx]) Jonathan intended to take hostages and force the liberation of the Soledad Brothers. He armed several convicts who were testifying in court and they seized the judge, prosecutor, and three jurors. The judge, Jonathan, and two of the convicts perished in a shoot-out before they could make their getaway. (Davis eventually faced trial for murder, but was acquitted, permitting her to forge a career as lifelong pain-in-the-ass to White America.)

Jonathan Jackson leading hostages out of the Marin County Courthouse. The judge has a shotgun taped around his neck.

In October 1970, Soledad Brother, Fay’s collection of George’s prison letters, was published. This led to a crisis. Jackson was unhappy that Fay toned down his image by deleting his more homicidal musings, and Jackson’s family and Black supporters were angry that White lawyers were claiming the royalties from the book for the Soledad Defense Committee. White supporters had already been the target of paranoid denunciations and even violence from Blacks around the case who didn’t understand the work they were doing or simply resented White solicitude.

The book portrayed prison officials as vicious racists and brought crushing press attention to bear on conditions in California prisons. It created a highly volatile situation in the prison system, endangering both guards and inmates.[xxi]

Jackson demanded that the money from his book, and other monies going to his Defense Committee, be diverted to his guerrilla army “training” in the Santa Cruz hills. Fay refused to cooperate, insisting they go to trial. It appears she shrank from a real plunge into violent revolution, although she considered Jackson a “comrade” in the “struggle.” Jackson somehow managed to divert defense money to his real comrades, and deceived his family about where the money went; the result was that his family and friends conceived a hatred for the “thieving” White lawyers. The disagreement between Fay and Jackson over the book royalties culminated in an “epic shouting match,”[xxii] and Jackson fired her, whereupon she quit.

It was February 1971. She was emotionally exhausted and sought comfort at home, reading novels in her bathrobe and putting on weight. Her marriage was turning sour again as well. Her departure from the case drained much of the life out of the effort: “quiet hopelessness has taken possession of everyone,” lamented a friend.[xxiii] Tragically, however, Fay would never be free of George Jackson. His Black followers quickly jumped to the conclusion that she was a “turncoat,” and their hatred would pursue her for years. The police would later uncover a “hit list” with Fay’s name on it. The only thing Fay had gained from working for Blacks was a deep sense of fear.

Fay and Prison Reform: the Prison Law Project

California wasn’t getting off that easy, however. Fay quickly floated a new venture, the Prison Law Project, with nine young female lawyers and assistants, including her lover. They intended to work on prison reform in general and render legal help to individual prisoners. Fay brought suits against the California prison system, gained grants from the federal government, and sparked legislative investigations of the prisons. Prison officials (who were working with poor human and financial resources) began to feel even more besieged. Conditions in the main prisons were bad, and some reform was necessary, but coupling this reform to a revolutionary agenda was equivalent to lighting a powder keg.

As soon as word got around the prisons about the project (and the young White females running it), letters flooded in from inmates pleading for their help. Again, the women were intoxicated in the presence of purported outlaws and revolutionaries. One of them later said, “Every visit was like a first date, like a drug.”[xxiv] Fay herself resumed her old ways; she was kicked out of one prison for making out with yet another Black convict, a man who later murdered two people.[xxv]

In late June 1971, Newton again went to trial for the murder of Officer Frey; it resulted in a hung jury thanks to a Hispanic female.[xxvi] A third trial also ended with a hung jury, and District Attorney Lowell Jensen reluctantly but wisely decided to drop the case.

Two months later, on August 21, the saga of George Jackson came to an end in San Quentin Prison, where he had been transferred. Somehow, he got hold of a gun, probably slipped to him by one of his radical lawyers. After a meeting with his new lawyers, he was taken back to his cell block, stopped and searched:

A clip of bullets hidden in his Afro wig clattered to the floor. Suddenly he was brandishing a 9-millimeter automatic . . . “The Dragon has come,” he said to the guards

. . . he ordered the cell blocks opened . . . There was a moment of euphoria and then the realization that there was nowhere to go. In the next few minutes, Jackson and his group of supporters released friends and rounded up guards and enemies. The scene quickly careened out of control; within minutes, three [White] guards and two White convicts lay in Jackson’s cell choking on their own blood, their throats slit by razor blades embedded in toothbrushes [Jackson shot one of the guards in the head point-blank]. As authorities moved to isolate the uprising, Jackson realized that the game was up. True to his vision of himself, he yelled to his friends, “It’s me they want!” and charged into the prison yard, firing blindly at the guard towers above, where sharpshooters lay on their bellies, waiting for him to come into their sights. The first of the two shots . . . splintered his shinbone; the next one caught him in the tenth rib, ricocheted up his spine, and exited the roof of his skull.[xxvii]

The news hit Fay very hard; she clearly still loved him. A week later the Weather Underground carried out three bombings in Jackson’s honor; later that year Bob Dylan recorded “George Jackson,” calling the vicious murderer “a man I really loved.” In early September, the inmates of Attica Prison in New York rose in rebellion; although they had not planned the uprising, the death of Jackson had triggered strong emotions among the prisoners. The revolt ended with the deaths of twenty-nine inmates and nine guards after a very heavy-handed suppression of the revolt.[xxviii] One can blame the cops for brutality, but obviously their fears had reached a pitch from years of agitation and the specter of prison revolt. Several factors combined to cause the unrest in American prisons in this era, but Fay Stender must take her share of the blame for her shamefully ignorant activism.[xxix] She made herself liable for blood.

When Fay decided not to defend Jackson’s prison buddies who carried out the bloodbath on the day he died (the “San Quentin Six), her Prison Law Project broke apart bitterly. The young hard-liners could not brook abandoning these prison “comrades.” Fay’s lesbian lover became her most severe critic, accusing her of running the law “collective” as an autocrat. Half of the Project split away to form a new legal team, and some of them never spoke to Fay again.[xxx]

Fay plunged ahead. In December 1972, she won a major “victory” against indeterminate sentences. Under these old guidelines, offenders would be sentenced to (say) “one to ten years,” and the system could then evaluate an offender and release him when he deserved it, or continue to hold him. When the California Supreme Court ruled against indeterminate sentences, it opened the door for—something Fay should have foreseen—mandatory longer sentences.[xxxi] The result was more prisoners and longer sentences. As so often, Fay’s activism had made conditions worse because she could not see the value of compromise.

By early 1973, her funds had run out, and Fay shut down the Prison Law Project. She was actually relieved. By this time, Fay had finally come to see the real nature of the convicts she had tried to help. She told Marvin that of all the men she had freed, “only one, absolutely only one, stayed out.” More than one had committed rapes or murders after being freed. She told a friend that hardcore convicts “had a screw loose somewhere . . . there was always a reason they were incarcerated.”[xxxii] What a tangled complex of feelings must have accompanied the epiphany! To her credit, she admitted her mistake to friends.

[i] Paul Liberatore, The Road to Hell: The True Story of George Jackson, Stephen Bingham, and the San Quentin Massacre. (New York: The Atlantic Monthly Press, 1996), 15-16.

[ii] Liberatore, 16-17.

[iii] Horowitz and Collier, 32.

[iv] Max Nelson, “Extreme Remedies” in The Paris Review, December 7, 2015. Accessed November 19, 2017: https://www.theparisreview.org/blog/2015/12/07/extreme-remedies/

[v] Horowitz and Collier, 32.

[vi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 168.

[vii] Ibid., 173.

[viii] Horowitz and Collier, 36.

[ix] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 205.

[x] Ibid., 157-58. The decision did not accept Fay’s argument about jury composition, but rather faulted the jury instructions of the judge.

[xi] Ibid., 214-15.

[xii] Ibid., 223-24.

[xiii] Horowitz and Collier, 37; Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 186-87.

[xiv] Douglas Perry, “Why Reedie and radical lawyer Fay Stender fought for prison reform – and paid with her life,” The Oregonian, June 27, 2015. Accessed September 14, 2017: http://www.oregonlive.com/living/index.ssf/2015/06/why_reedie_and_radical_lawyer.html

[xv] Horowitz and Collier, 36.

[xvi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 204

[xvii] Ibid., 204.

[xviii] Ibid., 242.

[xix] Horowitz and Collier, 40.

[xx] Liberatore, 82.

[xxi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 228-29.

[xxii] Horowitz and Collier, 40.

[xxiii] Horowitz and Collier, 41.

[xxiv] Eve Pell, We Used to Own the Bronx: Memoirs of a Former Debutante. (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009), 175. The quote is from Erlinda Castro.

[xxv] Ibid., 182-83, 186.

[xxvi] Pearlman, American Justice, 394.

[xxvii] Horowitz and Collier, 42-3.

[xxviii] Larry Getlen. “The True Story of the Attica Prison Riot.” New York Post, August 20, 2016. Viewed October 1, 2019: https://nypost.com/2016/08/20/the-true-story-of-the-attica-prison-riot/

[xxix] A commission called by California Governor Reagan to investigate the Jackson affair placed much blame on Stender and the “bad press Stender had generated about Soledad Prison . . . Prison officials insisted Stender had egged on the prisoners’ rights movement by spreading false and incendiary charges of inmate mistreatment and baseless and lawsuits.” Pearlman, American Justice, 404.

[xxx] Horowitz and Collier, 44-45.

[xxxi] Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 281.

[xxxii] The first quote is from Horowitz and Collier, 46; the second is from Lise Pearlman, Call Me Phaedra, 283.

https://12bytes.org/17748/important-rosa-koire-un-agenda-2030-exposed-video

“abolition. . .of private property”. . .Marx, Communist Manifesto

Excellent series of articles. Back in the days of the Weathermen, SDS, hippies, and the rest of the juvenile delinquents running amok across the country, our local paper carried a series of articles explaining the motives behind the radicals and their vision for a new America. While some people were sympathetic to the idea of formal racial equality, they all got sick once they read about the violent and perverted shenanigans of the main leftist players. That’s why Richard Nixon trounced liberal snowflake McGovern in 1972 – who got on board with some of the milder left-liberal recipes for transforming America.

America’s founding was a great event in the history of the world. But the founding and its eventual establishment into the 19th and 20th centuries allowed for the incorporation of alien peoples that were never going to be assimilated into a basically Northwestern European cultural setting. This in my view comprises America’s past and current tragedy. That’s why we had Fay Stender and all of her buddies.

If our civilization degrades, there will be some people who’ll be determined to do something about it. Arguing for an ideal of no planning, won’t impress them; as the clean water disappears, etc. So, something will get done. A call to resist, even for people to join together in resistance, isn’t actually presenting a positive alternative. The only real/sustainable path, is to develop an alternative planning process. Sure, socialism-from-above is a nightmare; which means, we must do socialism-from-below. Free individual neighbors must pool some resources, for common, community projects. Corporate-control is our default societal condition. We can submit to that; or, we can co-operate. Indulging in our individual freedom, may be a romantic stance; but, socially, it’s a dead end. We can work together, and learn group-decision-making (or so I want to believe…). Assuming, of course, that we wanted to leave the 7th-generation-yet-unborn, with a well world. As for the leftist lawyers here portrayed, at least they were trying to take some responsibility for an overwhelmingly mismanaged country. Naturally, they made stupid mistakes, especially when young; but that’s normal. And, yeah, sure, we can learn from their mistakes. Then, we can make new mistakes. Most people just pursue their own advantage, with no concern for the benefit of the whole. Is that truly natural? Rather, it’s natural to sacrifice, to some degree, for the benefit of the whole; because no tribe could survive without that characteristic within its members. That’s what we mean by, ‘Duty’ & ‘Honor.’ We erect monuments to the people who stepped up. Were any of those heroes perfect? No, they represent an ideal. Like the wacky leftist lawyers of the ’60s and ’70s. Wildly imperfect, but at least they cared for the big picture. They weren’t all about covering their own asses. They stuck their necks out; with all their Human foibles attached. America, including (perhaps even especially) some of her Jews, takes Freedom and runs with it, every which way. Long may it wave.