Mark Rothko, Abstract Expressionism, and the Decline of Western Art, Part 2 of 3

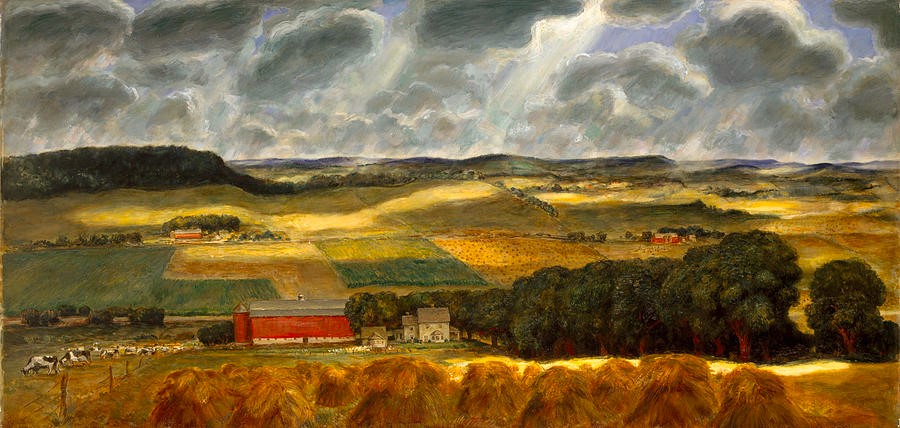

Wisconsin landscape by John Steuart Curry (1938-39)

Creating a New “American” Art

Before the rise of Abstract Expressionism in the 1940s, the American art scene was defined by two main currents. The first were the Regionalists (e.g. Grant Wood, Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry) who used their own signature styles to portray the virtues of the hard-working rural American population. The second group were the artists of Social Realism (e.g. Ben Shahn and Diego Rivera), whose work reflected urban life during the Great Depression and their devotion to international socialism. Neither was interested in abstract art, and despite their political radicalism the Social Realists held rather conservative attitudes to figurative representation. While these two styles dominated, the artists of the nascent New York School “met frequently at the legendary Cedar Bar, where they discussed their radical theses. They argued endlessly about the problems of art, about how to effect a total break with the art of the past, about the mission of creating an abstract art that no longer had anything to do with conventional techniques and motifs.”[i]

The Museum of Modern Art did not yet exist; the Metropolitan Museum tended to “look down its WASP patrician nose at modernism;” and the Whitney favoured exactly the kind of American painting young Rothko most despised: scenic, provincial, anecdotal, and conservative.[ii] For a Jewish outsider like Rothko, who in 1970 declared that he would never feel entirely at home in a land to which he had been transplanted against his will, urban America was his America.

But what was on the mid-town gallery walls was, for the most part, another America altogether: big Skies, fruited plain, purple mountain majesty, the light of providence shining on the prairie. About that America Rothko knew little and cared less. Early on, he had the sense that America ought to offer an art that was as new and vital as its history; but he also wanted that art to play for high stakes, to be hooked up somehow to the universal ideas he was chain-smoking his way through. Just what such an art might look like, however, he had as yet not the slightest idea.[iii]

The New York Intellectuals (who were overwhelmingly Jewish) associated rural America with “nativism, anti-Semitism, nationalism, and fascism as well as with anti-intellectualism and provincialism.” By contrast, urban America was associated “with ethnic and cultural tolerance, with internationalism, and with advanced ideas.” Their basic assumption was that rural America “with which they associated much of American tradition and most of the territory beyond New York” had “little to contribute to a cosmopolitan culture” and could therefore be dismissed.

Artistic Expression as “Unrelated to Manual Ability or Painterly Technique”

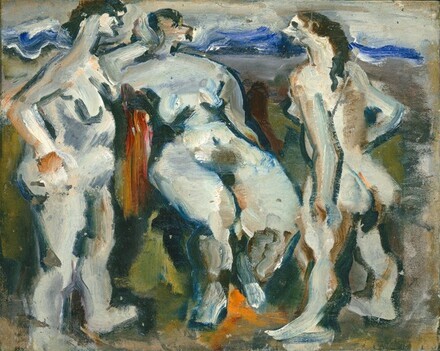

Rothko’s skill in rendering the human form was poor, which is evident in early works like Bathers or Beach Scene (Untitled) (1933/4). Schama admits as much, noting that: “When he [Rothko] stood in the Brooklyn [Jewish Center] classroom [where he taught art classes from 1929–46] it all seemed so easy. He would tell the children not to mind the rules — painting, he said, was as natural as singing. It should be like music but when he tried it came out as a croak. It’s the work of a painfully knotted imagination. No not very good.”[iv] According to the general consensus, Rothko “never stood out as a great draughtsman and could even at times appear clumsy in the execution of his oil paintings.”[v]

Bathers or Beach Scene by Mark Rothko (1933–34)

Rothko, in a speech in the mid-thirties, offered a quasi-philosophical rationale for the unimportance of technical skill, stressing “the difference between sheer skill, and skill that is linked to spirit, expressiveness and personality.” He insisted that artistic expression was “unrelated to manual ability or painterly technique, that it is drawn from an inborn feeling for form; the ideal lies in the spontaneity, simplicity and directness of children.”[vi] Such grandiloquent pronouncements from Rothko were not unusual, with Collings noting that “Rothko was outrageously over-fruity and grandiose in his statements about art and religion and the solemn importance of his own art.”[vii]

This tendency on his part prompted one writer to declare: “What I find amazing … is how a painting which is two rectangles of different colors can somehow prompt thousands upon thousands of words on the human condition, Marxist dialectics, and social construction.” He suggests a good rule of thumb is “the more obtuse terms an artist and his supporters use to describe a work, the less worth the painting has. By this definition Rothko may be the most worthless artist in the history of humanity.” Another critic humorously observed that:

Rothko needed to be fluent in rationalizing his existence and validating himself as a relevant artist to the average idiot who spent tens of thousands of dollars on paintings which could be easily reproduced by anyone with a pulse and a paint brush. Rothko … learned to garner attention to his paintings by getting into a frenzied drama-queen state and hysterically claiming that his works were deep, profound statements and not just indiscriminate blobs of color. They were expressions that rejected society’s expectation of technical expertise, actual talent and an artist’s evolution over time.

As well as self-interestedly seeking to redefine the nature of great art, Rothko often spoke out for the importance of “artistic freedom,” which in practice meant artistic freedom for those on the left. He became involved in the famed 1934 incident between John D. Rockefeller and the Social Realist painter, Diego Rivera. This began when Rivera was commissioned to paint a huge mural in the lobby of the main building of Rockefeller Center, the newly completed showcase of the oil baron’s ideals. Shortly before Rivera completed his work, Rockefeller dropped in and saw that the mural had a defiantly socialist message based on a heroic depiction of Lenin. He ordered the removal of the mural, resulting in its destruction. After this incident, a group of 200 New York artists gathered to protest against Rockefeller, and Rothko marched with them.[viii]

Part of Diego Rivera’s mural for Rockefeller Center

Jewish Ethnic Networking and “The Ten”

In 1934 Rothko was one of the original 200 founding members of the Art Union and Gallery Secession which was devoted to the newest artistic tendencies. A year later he became a member of the group who called themselves “The Ten” (the minimum number of Jews that can pray together). This unashamed exercise in Jewish ethnic networking was an opportunity for Rothko and his colleagues to engage in mutual admiration and promotion, and agitate in favor of “experimentation” and against “conservatism” in museums, schools and galleries.[ix] Among “The Ten” were Ben Zion, Adolph Gottlieb, Louis Harris, Yankel Kufeld, Louis Schanker, Joseph Solman, Nahum Chazbazov, Ilya Bolotovsky and Rothko. Gottlieb, in describing the group, later recalled: “We were outcasts, roughly expressionist painters. We were not acceptable to most dealers and collectors. We banded together for the purpose of mutual support.” “The Ten” acted as an alliance against the promotion of Regionalist art by the Whitney Museum of American Art, which to them was too “provincial” for words.[x]

Rejecting the local artists’ Regionalist perspectives, they were unable to define themselves as mere U.S. citizens. Instead, they presented themselves as cosmopolitan internationalists, freer and more open to incorporate the intercultural lessons of the European Modernist avant-gardes. When the fascist regimes began to decapitate these new art movements (with the closing of the Bauhaus in 1933 and the mounting of the exhibition Entartete Kunst [Degenerate Art] in Munich in 1937), great masters like Josef Albers and Piet Mondrian made their way to the United States, and American Jewish artists welcomed them with open arms.[xi]

The pronounced ingroup-outgroup mentality of “The Ten” mirrored that within the Jewish intellectual movements reviewed by Kevin MacDonald in Culture of Critique, where he notes how Norman Podhoretz described the group of Jewish intellectuals centered around Partisan Review as a “family” – a sentiment derived from their “feeling of “beleaguered isolation shared with masters of the modernist movement themselves, elitism – the conviction that others are not worth taking into consideration except to attack, and need not be addressed in one’s writing; out of the feeling as well as a sense of hopelessness as to the fate of American culture at large and the correlative conviction that integrity and standards were only possible among ‘us.’”[xii]

Within these alienated and marginalized Jewish groups was an atmosphere of social support that fostered an intense “Jewish ingroup solidarity arrayed against [what they saw as] a morally and intellectually inferior outside world.”[xiii] Despite the ethnic superglue, there were tensions within the Jewish milieu of “The Ten,” with Schama pointing out that, ”Amidst the usual Talmudic bickering of leftist factions, the denunciations and walk-outs, Rothkowitz and his comrades were all burning to make an art that would say something about the alienation, as they saw it, of modern American life.”[xiv] For Rothko, “the whole problem of art was to establish human values in this specific civilization.”[xv]

Isolationism as “Hitlerism”

Jewish gallery owners like Sam Kootz decried the “nationalist” art of the Regionalists and promoted the internationalist art of a rising generation of (often Jewish) expressionist, surrealist and abstract artists. “America’s more important artists are consistently shying away from Regionalism and exploring the virtues of internationalism,” he commented at the time. “This is the painting equivalent of our newly found political and social internationalism.”[xvi] For Rothko, like for most American Jews, the Second World War was a moment of universal moral crisis. He had only become an American citizen in 1938 and like many American Jews, “he was worried about the rise of the Nazis in Germany and the possibility of a revival of anti-Semitism in America, and U.S. Citizenship came to signify security.” Following the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact of 1939, Rothko along with others left the American Artists’ Congress to protest its continuing support for the Soviet Union.

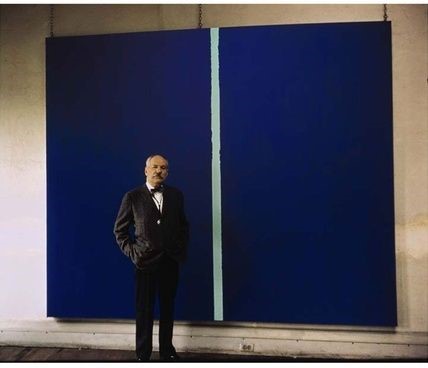

When on the first anniversary of Pearl Harbor, the Metropolitan Museum organized an exhibition entitled Artists for Victory, consisting of 1,418 works by contemporary artists—John Steuart Curry took first prize—the Federation of Modern painters vehemently criticized the works, denouncing them as “realist and isolationist.”[xvii] Jewish abstract artist Barnett Newman took a clear stand against local American artists, declaring: “Isolationist painting, which they named the American Renaissance, is founded on politics and on an even worse aesthetic. Using the traditional chauvinism, isolationist brand of patriotism, and playing on the natural desire of American artists to have their own art, they succeeded in pushing across a false aesthetic that is inhibiting the production of any true art in this country…. Isolationism, we have learned by now, is Hitlerism.”[xviii]

Jewish artist Barnett Newman with his “true”art untainted by “Hitlerism”

Jewish artist Barnett Newman with his “true”art untainted by “Hitlerism”

Rothko enthusiastically celebrated American entry into the war, insisting that it represented “an escape from narrow-minded isolation,” and “a reconnection with the destinies of modern history.” Schama observes that:

Now Rothko and his painter friends — so many of them originally European Jews — wanted American art to go the same way. With European civilization annihilated by fascism, it was up to the United States to take the torch and save human culture from a new Dark Ages. It was not just a matter of offering safe haven to the likes of Piet Mondrian or Guernica, but rather the authentic American way — doing something bold and fresh, taking the fight to the enemy which had classified modernism as “degenerate” and had done its best to destroy its partisans. … The Nazis had art (as well as everything else) entirely the wrong way round. The modernism they demonized as “degenerate” was in fact the seed of new growth, and what they glorified as “regenerate” was the stale leavings of neo-classicism. Their mistake was America’s — and particularly New York’s — good fortune.

This was a time when many American Jews were changing or modifying their names to sound less Jewish. In January 1940 Marcus Rothkowitz officially became Mark Rothko. During the war years Rothko’s art changed too: he produced a series of surrealistic pictures inspired by Freud’s interpretations of dreams, C.G. Jung’s theories of the collective unconscious, and ancient Greek mythology. Nietzsche’s The Birth of Tragedy was an important influence at this time.[xix] One source claims that “Amid an era of rising anti-Semitism, such themes enabled Rothko to address the unfolding catastrophe in Europe without publically proclaiming his status as a Jew.”

The Jewish Ethnic Networking Finally Pays Off

In the 1940s, Rothko’s intensive Jewish ethnic networking started to bear tangible fruit. He befriended Peggy Guggenheim, “the most voracious patroness of American avant-garde art,” who had migrated to New York in 1941. Guggenheim’s artistic consultant, Howard Putzel, “convinced her to show Rothko in her Art of This Century gallery, where she had opened in 1942, during the low point of the war.”[xx] In 1945, Guggenheim decided to put on Rothko’s first one-man exhibition at her gallery.[xxi] In 1948, Rothko invited a coterie of mainly Jewish friends and acquaintances to view his new “multiforms.” The prominent Jewish art critic Harold Rosenberg found these works “fantastic,” and called the experience “the most impressive visit to an artist” in his life.”[xxii] Rothko returned the favor, lauding Rosenberg as “one of the best brains that you are likely to encounter, full of wit, humaneness and a genius for getting things impeccably expressed.”[xxiii]

One of Rothko’s “fantastic” multiforms

When, in late 1949, Sam Kootz inaugurated his new gallery, he asked Rosenberg to select the artists for the opening show, and Rothko was inevitably among them. That year Rothko produced his first “color field” paintings, describing his new method as “unknown adventures in unknown space,” free from “direct association with any particular, and the passion of organism.” 1949 was also the year Jewish art critic Clement Greenberg expressed the hope that “national pride will overcome ingrained philistinism and induce our journalists to boast of what they neither understand nor enjoy.” Greenberg’s article appeared in the Nation on June 11, and two months later, journalist Dorothy Seiberling took up Greenberg’s challenge in an article in Life Magazine entitled: “Jackson Pollock: is he the greatest living painter in the United States?” This article, published in a magazine with a circulation of five million, made Pollock and the Abstract Expressionists famous.[xxiv] Subsequent articles by Sieberling sought to “make Abstract Expressionists like Mark Rothko, Willem de Kooning and Franz Kline accessible to a somewhat perplexed public.”

When, in 1950, the Metropolitan Museum announced an exhibition entitled American Painting Today, Rothko’s Jewish colleagues Adolph Gottlieb, Barnett Newman and Ad Reinhardt, in a letter published in the New York Times, lashed out at the curator for being hostile to “advanced art,” accusing the director of “contempt for modern painting,” and lamenting that “a just proportion of advanced art” had not been included in the upcoming exhibition.[xxv] Rothko was moved at the time to flatly reject the “whole tradition of European painting beginning with the Renaissance.” “We have wiped the slate clean,” he declared. “We start new. A new land. We’ve got to forget what the Old Masters did.”[xxvi]

In the 1950s, Rothko had arrived at his mature style, and with Katherine Kuh and Sidney Janis as his professional agents, “enjoyed both fame and material success at last.”[xxvii] Rothko’s professional ascent was fostered by these two eminent personalities of the art world: Kuh was the curator of the Art Institute in Chicago; and Janis an art dealer with the power to make or break reputations. In her biography of Rothko, Annie Cohen-Solal emphasizes the role of Jewish ethnic networking in Rothko’s rise from obscurity to celebrity in the American art scene. “Of all the ‘dynamic players’ instrumental to anchoring Rothko’s position as artist in American society,” she notes, “how not to mention that these two, in particular, were ‘assimilated’ Jews?”[xxviii]

Influential Jewish art dealer Sidney Janis

As soon as she became curator of the Art Institute’s painting department in 1954, Kuh proposed a solo show of Mark Rothko, and following the exhibition, the Institute “proudly announced that the museum had purchased No. 10, 1952, for its permanent collection. ‘It is needless to tell you how greatly this transaction contributes to the peace of mind with which my present work is being done,’ Rothko admitted to Kuh.”[xxix] Meanwhile, taking on Sidney Janis as his dealer in 1954 “marked a shift into higher gear” that resulted in a “spectacular windfall for Rothko.”[xxx] Janis signing up and actively promoting Rothko settled his status “as a protagonist of international importance in the post-war art scene.” After this, Rothko’s art was declared a good investment by Fortune magazine, which led to his relationship with colleagues Clifford Still and Barnet Newman deteriorating to the point where “They accused Rothko of harbouring an unhealthy yearning for a bourgeois existence, and finally stamped him as a traitor.”[xxxi] Sales of Rothko’s work would only improve when, a few years later, Congress passed a new tax law particularly advantageous to art collectors.

The Seagram Murals

In 1958, Rothko received a contract to paint murals for the Four Seasons restaurant in the Seagram’s Building in New York. The man who approved the commission was Seagram’s American subsidiary head Edgar Bronfman Sr.—later to become President of the World Jewish Congress. The fee offered was $35,000 (a huge sum at the time). Rothko was, however, uncomfortable with the commission and the damage it might do to his bohemian reputation, and subsequently refunded the money and asked for the completed murals to be returned. The idea that his “Seagram murals,” conceived as deep metaphysical statements, would become mere background decorations, was intolerable. Nine of them were permanently installed in a room at the Tate Gallery in London in 1970.

According to an unsigned source, Rothko’s color field paintings of the 1950s and beyond “can be seen as profound mediations on the Holocaust,” with their rectangular forms inviting “associations with the haunting images of mass graves seen in American newspapers and magazines during and after the war.” The dark tones of Rothko’s Seagram murals are described as “doorways to Hell” and “likened to the rims of flames: responses with obvious Holocaust resonance.” These paintings are widely held to be Rothko’s greatest achievement. Rothko certainly thought so, immodestly equating them with Michelangelo’s frescoes in the Sistine Chapel.[xxxii]

Rothko’s Seagram Murals at the Tate Modern

1961 marked the climax of Rothko’s public recognition as an artist with a comprehensive exhibition of his work at MoMA. The man responsible, MoMA’s Jewish curator, Peter Selz, raved about “these silent paintings with their enormous, beautiful, opaque surfaces [that] are mirrors, reflecting what the viewer brings with him. In this sense, they can be said to deal directly with human emotions, desires, relationships, for they are mirrors of our fantasies and serve as echoes of our experience.”[xxxiii] Selz, alongside fellow Jew Alan Henry Geldzahler at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, was one of “New York’s reigning curators,” was, like Rothko, “born into a European-Jewish family, but he came from Munich and had immigrated to the United States in 1936, driven out of Germany by the rise of Nazism.”[xxxiv] For Rothko, “who had already encountered various secular Jews in his professional trajectory—from Peggy Guggenheim to Sidney Janis, Katherine Kuh, and Phyllis Lambert”—Peter Selz would be the one to stage Rothko’s most prestigious exhibition in the United States.”[xxxv]

Despite the cheerleading of New York’s Jewish-dominated art establishment, a few critics resisted the enthusiasm for Rothko, most notably the gentile Howard Devree who, regarding Rothko’s paintings, noted that “the impact is merely optical rather than aesthetic, the validity as a work of art negligible. Seemingly it has become necessary for the color group to increase the size of their paintings, with corresponding emptiness; to make impact and size equivalent; and, as a corollary, they escape making any valid statement.” Devree compared Rothko’s paintings with “a set of swatches prepared by a house painter for a housewife who cannot make up her mind.”[xxxvi]

Works of ineffable genius or “a set of swatches prepared by a house painter

for a housewife who cannot make up her mind?”

Critic Emily Genauer described Rothko’s paintings as “primarily decorations,” which for Rothko was the ultimate insult. Rothko’s works were, she opined, “less paintings, as a painting is generally conceived, than theatrical curtains or handsome wall decorations.” Leading art critic and historian, John Canaday, observed “Mr Rothko’s progressive rejection of all the elements that are the conventional ones in painting, such as line, color, movement and defined spatial relationships,” before dismissing his work as “high-flown nonsense.”[xxxvii] Doubtless with Devree, Genauer and Canaday in mind, Rothko, who was intensely protective of his memory and paintings, once declared: “I hate and distrust all art historians, experts and critics.”[xxxviii]

The Rothko Chapel

In 1965 Rothko was commissioned by the oil tycoon John de Menil and his wife Dominique to paint a series of panels for a chapel in Houston, the city where they lived. Rothko adorned this chapel — a small, windowless, geometric, postmodern structure — with a collection of dark (almost black) murals essentially devoid of any content. The Jewish head of MoMA, Peter Selz, inevitably declared these paintings masterpieces, insisting that “like much of Rothko’s work, these murals seem to ask for a special place apart, a kind of sanctuary, where they may perform what is essentially a sacramental function…”[xxxix] Dominique de Menil claimed to be similarly impressed, asserting that Rothko’s colors “became darker, as if he were bringing us to the threshold of transcendence, the mystery of the cosmos, the tragic mystery of our perishable condition.”[xl]

Rothko Chapel Murals: bringing us to the “threshold of transcendence?”

Rothko’s place at the summit of the New York art world was threatened three years after his MoMA exhibition when the Golden Lion was awarded to Robert Rauschenberg at the Venice Biennale of 1964. This gave prominence to the emerging artists of the Neo-Dada and Pop Art movements, and made Abstract Expressionists like Rothko seem passé.

In 1968, Rothko was diagnosed with a mild aortic aneurysm. Ignoring his doctor’s orders, he continued to drink and smoke heavily, avoid exercise, and ignore dietary prescriptions—which also exacerbated his depression and seclusion. He died in his studio on February 25, 1970 after overdosing on anti-depressants and cutting his right arm with a razor blade. He was 66 years old and left no suicide note. After Rothko’s death, 798 of his works were “procured” by his then dealer, Frank Lloyd, the Jewish director of the Marlborough Gallery, in dubious circumstances. The lengthy legal proceedings this initiated became emblematic of mounting financial corruption in the art world, and led to a growing distrust of art dealers among Americans.[xli]

Conclusion

Opinions vary widely about Rothko’s work and legacy. Many within the Jewish-dominated art establishment hail him as a genius, a creator of transcendental, spiritual works for secular times. Others cannot believe that any sane person would pay hundreds of millions of dollars for what amounts to nothing more than a large, empty canvas occupied by two colors divided into separate rectangles by a third color. What is clear, however, is that Rothko’s career and burgeoning posthumous reputation have been overwhelmingly the result of shameless barracking and hyping on the part of the Jewish intellectual and cultural establishment. Rothko’s son had the chutzpah to draw a parallel between his father’s work and that of Mozart, insisting that his father’s paintings are “the visual embodiment of a Mozart composition.”

Jews have long used their cultural dominance to construct “Jewish geniuses” to foster ethnic pride and group cohesion. It has been (and remains) a standard feature of Jewish intellectual life in the West to wildly exaggerate the significance of Jewish scientists, writers, composers, artists and intellectuals (often while downplaying the achievement of their non-Jewish peers). The absurdly exalted status accorded to Mark Rothko and his oeuvre is emblematic of this practice. Rothko is surely an artist for whom the expression “the emperor has no clothes” is particularly apposite.

[i] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 10.

[ii] Schama, Simon Schama’s Power of Art, 403.

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Schama, Simon Schama’s Power of Art TV Series.

[v] Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko, 64.

[vi] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 24.

[vii] Matthew Collings, This is Modern Art (London: Weidenfeld & Nicholson, 1999), 169.

[viii] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 26.

[ix] Schama, Simon Schama’s Power of Art, 405.

[x] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 26.

[xi] Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko, 7

[xii] In MacDonald, Culture of Critique, 217.

[xiii] Ibid., 218.

[xiv] Schama, Simon Schama’s Power of Art, 406.

[xv] Schama, Simon Schama’s Power of Art TV Series.

[xvi] Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko, 90.

[xvii] Ibid., 79.

[xviii] Ibid., 88.

[xix] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 33.

[xx] Ibid., 38.

[xxi] Ibid., 39.

[xxii] Ibid., 45.

[xxiii] Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko, 97.

[xxiv] Ibid., 116.

[xxv] Ibid., 121.

[xxvi] Ibid., 126.

[xxvii] Ibid., 153.

[xxviii] Ibid., 138.

[xxix] Ibid., 144.

[xxx] Ibid., 117.

[xxxi] Baal-Teshuva, Rothko, 50.

[xxxii] Norbert Lynton, The Story of Modern Art (Oxford: Phaidon, 1989), 242.

[xxxiii] Cohen-Solal, Mark Rothko, 174.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 175.

[xxxv] Ibid.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 147.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 176.

[xxxviii] Ibid., 161.

[xxxix] Ibid., 185.

[xl] Ibid.

[xli] 206

Truly an excellent example of “The Emperor Has No Clothes” tale. I pity the throngs of people standing silently in front of his works – everyone afraid to be the first to say “Really??? Does this guy really think he can pass this off as anything more complicated than a childish painting practice?”

I expect to be in the minority here, but I must say articles like this which bring the old punching bag of abstraction out for a few hearty, group-bonding attacks are a bit too predictable. This is not a simple issue. Realism in art entered a period of crisis in the mid-19th c. as photography developed. Art had to find other ways to earn value and relevance for itself apart from more-or-less exact or skillful imitation.

If you value manual skill above all else there is plenty of art, both historical and modern, to enjoy. One of the problems with realism is that it must always steer a course between “prettiness” and kitsch. There is a good deal of Art from the period under review that is realist and quite good. Thomas Hart Benton is an exemplar of American values and he produced quite good art,including some masterpieces.

On the other hand, the faux-childish and over-rated figurative art of the Jew Marc Chagall manages to be both (somewhat) realist and cloying; Jewish sentimentality made manifest.

The real crisis of realism has much to do with the increasing capabilities for graphic reproduction in the late-19th and early 20th centuries. Salon-style paintings began to find their way onto calendars, advertisements, and candy boxes. It’s only about a half-step from the technically magnificent work of a Bouguereau to the sugary disposability of Victorian souvenir china.

Perhaps in part because of the physical ugliness of most Jewish men, I do think they are capable of deep feeling in their particular areas of expertise. Not nobility or heroism, mind you. But profundity- yes, not unlike the profundity of some sections of the Hebrew Old Testament.

More generally, large art movements tend to respond to, and eventually represent, their own time. Abstract Expressionism, for better or worse, is the American art par excellence for the 1940’s and 1950’s (only to be displaced by Pop Art in the 1960’s).

This doesn’t even begin to address the commodity issue; if we are going to be outraged by the price of a Rothko, we might as well be outraged by the price of a Van Gogh, or a Rembrandt. There are plenty of skilled artists who could whip you up a dead-on copy of “Laboureur dans un champ”, but don’t expect it to be worth 81 million dollars. In fact, I personally know artists who could paint an even more realistic, tightly-rendered version of that work, if that’s where you place the value.

But no, the actual Van Gogh is fantastically valuable due to who painted it; same with the Rothkos that find their way to market.

Yes, there was a Jewish conspiracy of sorts to market avant-garde art; just as there are Jewish conspiracies to market Hip-Hop music; Jews are quite good at manipulating markets, and even creating them in the first place. The question of the value of the product can be discussed aside from the mechanisms that were used to monetize them. I would maintain that some Abstract Expressionist works were and are capable of conveying meaning and from which aesthetic pleasure can be derived.

I don’t think abstraction, per se, is the target here. It’s certainly not for me. Rather, it’s abstraction coupled with what one might call “anti-realism” and the “deconstruction” of traditional western art. Combine these with heavily Jewish control and Jewish dislike for the host nation’s traditions and culture, and you’re no longer talking about a mere dispute over aesthetics.

I’m surprised anyone would suggest that realism in art became problematic because of the rise of photography or of cheap reproductions on china and so on. People admire art for the skill with which it is executed and the imaginative vision of the artist. Photography has not eliminated the pleasure we take in seeing fine art close up and in person.

“…must steer a course between ‘prettyness’ and kitsch…”

Is beauty kitsch? This sounds like a Marxist critique of bourgeois aesthetics. But it was the bourgeoisie — broadly defined to include kings, emperors and popes — that gave us the opportunity to experience art in the first place.

Art cannot exist without leisure and/or patronage. The working classes are too busy working, the serfs too busy reaping and sowing, the slaves too busy serving their masters, to create art. And they don’t have the money to pay artists.

Marxist art criticism (which is pretty much all art criticism today, I gather) is necessarily anti-art. Being heavily Jewish — with Jews having no talent for art — what we end up with is propaganda and “anti-art” in the form of “deconstruction” of past art.

If the “avant-garde” presumes to actually make art instead of just criticizing and gatekeeping, then you can only have art in the form of passing fashions.

That’s what began to happen at the end of the nineteenth century and continues to this day. It is an art fit only for an alienated and fad-driven people. Given that both capitalism and communism are forms of alienation, this unappealing art can get by. The powers that be — governments, foundations, philanthropists — will prop it up and support it.

But it isn’t loved or even liked. It would disappear altogether if it didn’t serve some unartistic useful purpose. What would that purpose be? Social engineering. By the Jews. They want to control the culture of their host nations. And they want to use that control to “socially engineer” the goyim to their liking.

To pull that off, control must be total. The Jews must take leading roles as curators, dealers, gallery owners, agents, philanthropists, critics, art professors, even artists themselves. And that is what they have done.

The question, then, is whether there is some great art out there — abstract or realist, or some combination thereof — that we are missing. The same could be asked about other fields whose “choke points” are controlled by the Jews. The answer is: We don’t know.

@Eric-

Thanks for your thoughtful and intelligent response. It was interesting to read, unlike the dreaded “my kid could make better paintings” type of argument one still encounters when the subject is abstraction in art.

One of the problems with framing these discussions as examples of Jews trying to tear down Western ideals of beauty is that Jews also profit from the sales of realist works. When Abstract Expressionism fell out of fashion, it was succeeded by Pop (representational) and a brief vogue for Super-Realism (hyper-representational). So to make a particular case of Abstract Expressionist art as a battering ram against the gates of Culture is somewhat inadequate. That argument had its cultural moment, but the Jews have more than one string to their bows, and Abstract Expressionism has long since stopped being any kind of threat to Western culture, if it ever even was one in the first place.

Also recall that Hitler scorned German Expressionism, even though there were some obvious bridges between that school and Nat. Soc. A missed opportunity, in my opinion; an embrace of the Expressionists could have won some cultural cachet for the Reich, and there is an undeniably “Germanic” quality to it. Some Nat.Soc. party luminaries had to dump their collections of the German Expressionists when Hitler voiced his rejection of the movement.

As for the issues of kitsch and mechanical reproduction, you are quite correct that much has been made of this subject by Jewish writers; however, they aren’t making it up in this case; there *are* certain conundrums involved with the multiple nature of machine reproduction v. the “original work of art”.

I would suggest that art is to some extent de-sacralized by its commercially infinite reproducibility. Is that a Marxist critique? I’m afraid it can’t be declared innocent of that charge, but my own eyes tell me that a rack of postcards reproducing the Mona Lisa complicates our relationship with the original. I don’t say it ruins our response, but it definitely complicates it.

If we make realism the gold standard of art’s qualitative worth, we somewhat impoverish ourselves.

You’re right that Jews would want to see a return on their investments in various kinds of art, including representational art. I’m would expect that Jews are even the proud owners of some Old Masters.

That doesn’t alter the fact that “deconstruction” of Western (goy) culture is a prime Jewish motivation.

I myself have never considered abstract expressionism to be an attack on Western culture. As I said before, it was the added elements of dogmatic anti-realism and manifest Jewish hostility to the host nation’s cultural traditions that that were — and remain — problematic.

Under Jewish influence, art has become like fashion. You’re either “in” or you’re “out,” and it’s the Jews who now make that decision.

Of course, art always evolved (or “progressed”) from one variety of expression to another, and it was possible to be regarded as “old fashioned” and irrelevant even when Jews did not have a lot of influence.

But they have heightened that tendency. And what they have promoted in recent years is frankly an insult to the host culture: outright obscenity, assaults on Christianity, art as crude (always left-wing) propaganda, constant denunciations of whites and Western civilization, and conceptual art that really does justify someone saying “my kid could do that.”

I agree with you about Hitler. He had a particular vision — one that I am afraid was limited. He was trying to restore what we might call “family values” to a decadent Germany. In the process of so doing, he tossed the baby out with the bath water.

But this only serves as more evidence of the bad influence of Jews on their host cultures. They basically drive them insane.

@Eric-

I completely agree with your assessment of the pernicious influence of the Jews on Western culture. I agree that certain schools of art, to which you refer, are almost entirely about attacking Western ideals and nullifying cultural norms. And Jews certainly use philosophical and attitudinal deconstruction as a weapon against social decency and especially any cultural nobility they find which might have so far escaped their efforts to eradicate it.

Where I take exception is to the rather simplistic appraisals of art works and movements based on a yardstick of verisimilitude. I find the Paleolithic cave paintings of Lascaux quite beautiful, but they are not terribly realistic. They convey an essence however, more vital than many a more accurate or detailed rendering.

I think an argument can be made that an artist like Jackson Pollock was expressing a Faustian and very Aryan quest for some eternal or transcendent state- though his ultimate sadness and failure to live a noble life should also serve as a cautionary note: perhaps about nihilism, or perhaps about self-indulgence.

What I argue against is oversimplification of the complex relationship we have to art. Abstract Expressionism carries some value imho, though I don’t believe that the painters who practiced it obviated other art styles. Realism retains its own satisfactions.

Nor does the fact that Abstract Expressionism has value automatically mean that all forms of non-representational art are created equal. Much of current art has no value other than its refusal of European heritage, a mere attempt at negation, as you seem to be (rightly) saying.

My original misgivings about the Rothko article are that it encourages a kind of knee-jerk ridicule which if not occasionally challenged, can lead to intellectual complacency.

JRM: Well said.

I think we are now in total agreement on all of these points.

Reminds one of a 1960 rock song MONA LISA by art critic Carl Mann: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZDqBIzbNt10

When I hear the word culture I release the safety catch on my squirt gun.

@ TJ

Good one! “kek” as they say on a certain other site…

In the ten years I spent in Denmark, I visited a lot of art galleries. Except for a few, all portrayed art that was basically garbage, garbage being too kind a word to describe the psychotic crap that was shown. And no one should take “modern” art seriously even if the point is to damn it. It’s beyond damnation and even damnation allows it a certain amount of legitimacy.

A favorite thing for me to do in the galleries was to observe the actions of the people coming in. Invariably, most patrons simply walked from one end of the gallery to the other in two or three minutes flat, barely pausing to gaze or study an art piece. After all, there really was nothing to look at. Attending a gallery event was more like simply something to do to trade one boredom for another.

I am pleased but not surprised he committed suicide. It seems like artistic types and entertainers are often mentally unbalanced. Rothko’s “creations” certainly showed this was tge case with him.

Everything the Jews touch turns to shit. Art, anthropology, psychology, corporate business, government, movies, music…everything.

The only solution for us is to get rid of these people. Peacefully if we can get it but by any means we must get rid of them. It’s the only solution that’s ever worked with these psychopaths. Ship them all to their shitty little country in Israel and let them rip each other off instead of us.

Couldn’t agree more.

I have it from reliable sources, that the woman pictured above at the Tate, engrossed by the masterpiece on the right, of the Seagram murals, has been waiting since they were first hung there, wondering when the video on this large screen will finally start.

I remember 20 years ago going to visit a modern art exhibit that was comprised by paintings someone had described in the newspaper as “degenerate garbage.” I remember studying the paintings and thinking, “How does that designation not apply to this crap?”

On another occasion, I visited the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C., which had included some barn board paintings alongside paintings of the great master artists of Europe. The barn board paintings, which were of cartoon-like quality, depicted the great migration of U.S. Negroes from the South to the North in the last century. At the end of the barn board exhibit was a book for comments, overseen by a closed circuit camera. I read through the comments, and was astonished to find they all gushed with praise and excitement. Somehow, I suspect that if the Phillips Collection had included some of those notorious paintings created by zoo elephants, the commentary would have been equally effusive.

The Jewish “fake intellectuals” have tried to destroy all kinds of classical achievements,including architecture, classical music & operas, poetry & literature,through their Jewish” pioneers of modernity”(sic),each in his field.

But I think they failed miserably, and succeeded only in enhancing the supremacy of the classical concepts arts & literature over the degenerate modern claims.

It’s amazing how the Jews can be so arrogant & ignorant in comparing the work of Michelangelo & Mozart to that of Rothko, I would like to ask anyone of those Jews: if there are two events at the same time, one for Mozart Don Giovanni & the other one is Rothko’s exhibition, and there is a free ticket to go to only one of them, which one they’ll chose?!

Actually, such outrageous claims exposes their hatred of geniuses like Mozart, Beethoven & Michelangelo, they know deep inside themselves that Stravinsky,Mahler, Schoenberg et all, are dwarfs next to those giants, so how come they are the “chosen people” when the gentiles are proving that they’re far superior?!

I hope that when the majority of people become fully aware of their repulsive & evil nature, they’ll be isolated and quarantined like virus infected carriers.

Stravinsky was not a Jew. Stravinsky is not a dwarf. Oy!

The remnants of Western Christian culture are almost as much at risk from soi-disant friends named Ahmad as from outright enemies named Rothko or Rosenberg.

Thank you, Pierre for mentioning my mistake about the religion of Stravinsky, But his music fits in serving the Jewish agenda mentioned in the article, and he’s still a dwarf to me,compared to Beethoven, Brahms, Sibelius…etc.,and you can have your own opinion.

But to equate me,(not for my mistake, but actually for my name),as “so-called” friend,and equally dangerous as a Jewish enemy, shows your racism,and intolerance of non Christians being accepted in criticizing the Jews.

Thanks Pierre for correcting my mistake about Stravinsky’s religion, but his music fit’s with the Jewish agendas & targets,and this is more important than whatever religion is.

And compared to Beethoven, Brahms, Sibelius, Mozart…etc, he IS a dwarf in my opinion, and you can have your own opinion;

But it seems that it’s not my mistake that upset you and made you equate me as dangerous as the Jewish enemies, and you put me in the soi-disant (so called) friends, but it was my name, which is not European, and not Christian, probably Muslim, and that’s unacceptable to you, because I think that you’re a racist, and you prefer a Jewish enemy over a non-Christian stranger.I wish you good luck in trying to preserve the soi-disant Judaic Christian culture.

Is there any sphere of life in America that has not been tainted by their sociopathy?

One can only fantasize what kind of a country America would be today without any of their harmful influences.

Draw two imaginary diagonal lines through his Beach Scene. From the upper left to the lower right, and from the upper right to the lower left: which, pursuant to geometry would be the exact center.

Where might they intersect ? The protruding hyena snouts of the women aside. Acceptable ART ? At least useful to cover a knothole in an Adirondacks cottage outhouse during winter !

Just as Rothko’s “art” is devoid of soul and content, any possible comment leaves me speechless and devoid of words. The jews are antithetical with nature and beauty. They seem to be agents of destruction regarding all things. What possible purpose do they serve in existence?

In short, he sucked at art.