Guillaume Faye Remembered

“Guillaume Faye was indeed an awakener.”

“Guillaume Faye was indeed an awakener.”

Pierre-Émile Blairon

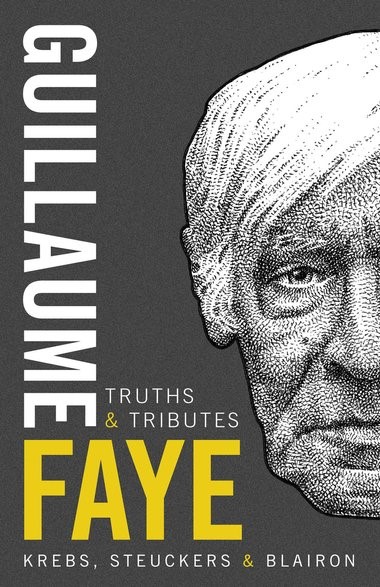

Guillaume Faye: Truths and Tributes

Robert Steuckers, Pierre-Émile Blairon, and Pierre Krebs

Arktos, 2020.

Guillaume Faye’s posthumously published Ethnic Apocalypse, or, to give it the original French title Guerre civile raciale (Racial Civil War), was one of my top three reads of 2019, so it was with great interest that I found out that Arktos was set to publish a volume of memories of Faye and reflections on his work. Faye passed away in March 2019, following a battle with lung cancer, and I recall thinking while reading Ethnic Apocalypse that its author seemed set to become one of those figures who make their greatest impact only after their death. Other than brief summaries of Archeofuturism: European Visions of the Post-catastrophic Age (1999), my primary encounter with Faye before reading Ethnic Apocalypse was a recording of the 2006 AmRen conference, during which David Duke took an opportunity in the middle of a question session following Faye’s speech to make known several historical facts relating to the specific issue of Jewish disloyalty. The footage shows Duke being interrupted and subjected to foul language by Jewish social scientist Michael Hart, apparently the sole malcontent, who then abruptly left the venue. The episode was certainly dramatic, and my sympathies firmly remain with Duke, but the chaos between Duke and Hart unfortunately overshadowed a very sophisticated response from the charismatic Faye that included the memorable line: “The Jews are good tacticians but have bad strategy — they do always too much, too much, too much.”

Faye’s relationship with the Jewish Question was very nuanced and, it must be admitted, at times completely wrongheaded, as illustrated by his handling of the topic in Ethnic Apocalypse which derived heavily from ideas conceived in his La nouvelle question juive (The New Jewish Question), published in 2007. The latter resulted in Faye being denounced at one point as a Zionist but, as I wrote in my 2019 review of the former text, “I firmly believe that Faye is not guilty here of subversion or fear of the Jewish lobby. If I did, I would hesitate to recommend this book. Instead, I see a paralysis-like error in thinking, brought about by a quite understandable reaction to the stark and visible Islamisation of France.”

This was one of my primary takeaway thoughts from that volume — that Faye was a great thinker, with wide interests and aptitudes, who at the end of his life was so gripped by the scale of the Muslim invasion of his beloved country that he could see no other threat, and perceive no other enemies. As such, I had an empathy for Faye, even where I could not agree with him, and I couldn’t help but be impressed with his authorial intensity and bluntness in expression. I was curious enough to start seeking out translations of his essays, particularly those concerning technology, civilization, and the system in which we now live. These have been educational and entertaining. I remained curious about the man behind them, however, and I therefore welcomed this new literary memorial from Arktos, which acts an illuminating, poignant, and unexpectedly tragic guide to Faye and his very considerable body of work.

The volume opens with a short and elegant Foreword by Jared Taylor, who performed the same task for Ethnic Apocalypse. Taylor, who also came relatively late to Faye but who appears to have become very good friends with him around 2003, rightly points out that “an intellectual history of Guillaume Faye is nothing less than an intellectual history of both the New Right and of the far bolder Dissident Right.” From there the text proceeds to a series of essays dominated by four contributions from Robert Steuckers, who knew Faye from the beginning of the latter’s career in the movement, and is able to flesh out a biography of his ideas and activism.

These essays by Steuckers are quite remarkable, and are impressive not only in their handling of the context and origins of Faye’s ideas, but also in the way the personality of Faye is always brought to the fore throughout. These are essays laced with sadness, even anger, however, because, in the perspective of Steuckers, Faye emerges as someone passionate but tragically naive — taken advantage of by organizational superiors. It must be stated that Alain de Benoist does not emerge well at all from this volume, described by Steuckers at various points in the text as lacking sincerity, seeking stardom, pallid, hyper-nervous, “the emblematic epitome of ingratitude,” and a boorish movement ‘pontiff.’” Above all, we see the energetic and talented Faye repeatedly pushed aside and paid minimal wages in order that other stars could shine brighter. The volume is thus a kind of fable for the darker side of movement politics and division that will probably always remain relevant.

But what of Faye? In his first essay, “Faye’s contribution to the ‘New Right’ and a brief history of his ejection,” we join Steuckers in the early 1970s, just as Faye was becoming politically active. Then in his early 20s, Faye “entered the scene virtually alone sometime between the departure of the partisans of the 1968 events and the arrival of the Reaganite ‘yuppies.’” His first involvement was with the ‘Vilfredo Pareto Circle,’ a political studies group loosely attached to, but later absorbed by, G.R.E.C.E. (Groupement de recherche et d’études pour la civilisation européenne (“Research and Study Group for European Civilization,” a thinktank that promotes the ideas of the New Right). Faye “was not attached to any branch of the conventional French Right,” nor had he any ties “to any Vichy or collaborationist circles, nor to those of the OAS [Organisation armée secrète, a paramilitary organization formed during the Algerian war] or the ‘Catholic-traditionalist’ movement.” Initially, Faye was not a nationalist in our understanding of the term, but rather a “disciple of Julien Freund, Carl Schmitt, Francois Perroux etc.” Steuckers describes Faye, the intense young political philosopher, as emblematic of a ‘regalian Right’ that “cast upon all events a sovereign and detached eye, which was not, however, devoid of ardour and ‘plastic’ will, sorting out in some way the wheat from the chaff, the political from the impolitic.”

In Steuckers’ eyes, “Faye was truly the driving force behind G.R.E.C.E., the New Right’s main organisation in France during the early 1980s.” He achieved this status through sheer hard work on weak wages, driven by passion and a desire to shock the ‘old Right” out of its comfort zone. Steuckers scathingly contrasts the idealistic Faye with a movement satisfied to “content itself with hastily camouflaging its pro-Vichy attitude, its colonial nationalism, its Parisian lounge-lizard Nazism, its purely material ambitions or its caricatural militarism under a few scholarly references.” Faye was quickly sidelined by the comfortable figures in the hierarchy, but “he never cared much about all those backstage intrigues; to him, what mattered was that texts were being published, and books and brochures spread to the public.” By the late 1970s, Faye’s charisma and intelligence is credited with bringing G.R.E.C.E. into contact with influential new circles, as well as students who “accepted the novelty of his speech and the essential notions it conveyed.”

One of Faye’s primary contributions to G.R.E.C.E. was his editorship of Éléments magazine, during which time he refined many ideas that would become characteristic of his later work: his criticism of the Enlightenment, his critique of Western civilization as something that has evolved into a “system that kills peoples,’ his concept of ‘ethnocmasochism,’ and his vision of technological progress as something that can be harnessed by nationalism rather than as something to be shunned or prevented. (Faye in this regard runs counter to more popular anti-technological positions adopted by Heidegger, Ellul, and Kaczynski.) Steuckers goes so far as to remark that “the glorification of technology and a rejection of archaising nostalgia are truly the main traits of Neo-rightism, i.e., of Fayean neo-rightism.”

Just how correct Faye was in this respect remains to be seen, but it is clear, in this age of increasing surveillance technologies and the mechanization of almost all aspects of life, that the question of technology is only going to become ever more prominent. Much as my own instincts tend to the anti-technological, it’s difficult to understand how one nation or ethnic group can divest itself from technological progress if this means ceding an advantage to other groups who won’t do the same. We may thus be locked into a technological arms race where our only option is to attempt to surpass all rivals in pursuit of what Faye called Archeofuturism.

In so many ways, Faye was a man ahead of his time — a fact that rises to the fore in the volume’s second essay, “Farewell, Guillaume Faye, after forty-four years of common struggle.” At a time when the youngest generation appears to believe it more or less invented shock humor tactics in politics, we gain some insight from this essay on Faye’s outlandish detour into prank comedy as the “Skyman” persona for the Skyrock radio station. This occurred in part due to his declining fortunes in G.R.E.C.E., which was in turn a result of the suppression or sabotage of his work. In one memorable instance, he was more or less forced by his superiors to follow up an intellectual exploration of Heidegger with an unironic piece on, of all things, Atlantis.

Operating on little more than enthusiasm, and lacking formal networking skills, Faye had nothing in place to support his work independently when he was finally ushered out in 1986 by a ‘core nucleus’ that had grown unhappy with his edgier direction and popularity. He then put his charisma and enthusiasm into a ten-year career in producing schoolboy-like sketches, hoaxes and jokes, one of which involved his fooling a substantial number of top-level French politicians by pretending to be on a secret mission from Bill Clinton to select the latter’s own secretary of state for European affairs. Faye played the role to a tee, presumably enjoying himself very much as these venal bureaucrats “jostled one another in a desire to get the job, maligning their own colleagues.”

Faye returned to political activism in 1997 in an interview for the then new magazine Réfléchir et agir. In the interview, Faye advised an intensification of associative action against “anti-European racism,” and when questioned about this in a later interview he trenchantly accused the French Right of engaging too much in infighting instead of pinpointing a common enemy:

The French national Right is undermined by the culture of defeat, petty bosses, gossip: the different groups of Muslims and Leftists can detest one other, but they have each and all the same enemies against whom they unite. Whereas for many people of our ideas, the enemy is at first his own political friend, for simple reasons of jealousy!

A year later, Faye returned to speaking engagements and published Archeofuturism, his response to “the catastrophe of modernity” and an attempt to provide an alternative to traditionalism. Although somewhat welcomed back into the New Right fold in 1998, when he published his edgy The Colonisation of Europe: True Discourse on Immigration and Islam in 2000, Faye attracted considerable hostile media and political attention. A move was apparently then undertaken by de Benoist and others to once against distance themselves from the more radical Faye in order to save face and respectability. One member was even discovered to have sent information on Faye to scores of journalists in an attempt to smear him as a “hothead” and “racist.” Steuckers alleges that de Benoist

proceeded to exclude him from all the bodies that he sponsored and banned his flock from spending time with him and publishing his books. Faye had thus suffered another terrible blow, one from which he would never recover and that would instill unabating despair into the very depths of his heart.

Faye would toil in relative obscurity for several more years until friendships with Americans like Jared Taylor and Sam Dickson, and a new relationship with Arktos Publishing under Daniel Friberg, brought Faye and his ideas into the Anglosphere in a serious way for the first time. Unlike the French scene, “within the vast American movement, no attempt to sabotage his books has ever taken place.” Within the American scene, Faye’s work received generous praise and treatment by websites like American Renaissance and Counter-Currents, and there are 20 essays at the Occidental Observer that touch in some way upon Faye’s writings. Anglosphere academics like Michael O’Meara have also given major attention to Faye, with O’Meara publishing his Guillaume Faye and the Battle of Europe in 2013. Faye’s books have been very well-received in the Anglosphere, as my own review of his last book indicates.

Although the biographical and bibliographical essays by Robert Steuckers form the backbone of Guillaume Faye: Truths & Tributes, I must say that one of my favorite essays in the volume is Pierre-Émile Blairon’s “Guillame Faye, an Awakener of the Twenty-First Century.” The tone is much little lighter than the previous essays, with less focus on the ways in which Faye was wronged, and a greater emphasis on his personal qualities as friend and political adventurer. Blairon recalls meeting Faye in the early days of his own activism and seeing in him “the brilliant spokesperson and inventive theorist for what would later be termed the ‘New Right’.” Blairon continues

I remember that, even back then, he was more than just an intellectual; he also had a sense of theatrics and farce and would delight us with improvised comedy playlets that made us laugh. Now, however, more than forty years later, History has issued its verdict — Guillaume Faye was much more than that.

For Blairon, Faye was “an Awakener:

Awakeners are men who come from an immanent , immutable, and permanent world, that ‘other world’ that lies parallel to ours, arriving here to accomplish a mission. These men have no other concern than to pass on their knowledge and energy; and their entire life ends up being devoted to this transmission. Awakeners appear in critical periods of history, when everything has been turned upside down and all values reversed, and when the situation seems desperate. They give their mission priority over their own person, their personal interest and comfort. Their rule of thumb is the following one: do what you must, without anticipating success.

The essay then moves to a succinct but excellent assessment of the main themes of Faye’s work: the fight against standardization and globalism; Europe as an entity of blood and soil rather than bureaucracy; Ethnomasochism; the convergence of catastrophes as a fundamental aspect of civilizational collapse; archeofuturism and technoscience; and, finally, Islam. For anyone new to Faye’s work, or seeking a refresher on some of the less well-known aspects of it, this volume is thus invaluable.

In addition to two poems by Pierre Krebs, the book significantly benefits from a section titled “Annexes,” which contains direct engagements with specific examples of Faye’s essays and books. The best of these, in my opinion, is Robert Steuckers’ review essay concerning Faye’s System to Kill People. In this work, Faye had argued that, diluted by massification and depersonalization, Western civilization no longer exists as a civilization but rather as a system that is directly hostile to the nationality of peoples and thus “kills” them. This basic idea is central to Faye’s anti-Westernism, which is itself founded on Faye’s general hostility to the Enlightenment. Faye lamented the reduction of our ethnic identities in a way that rendered them “folklorised,” “ornamentalised” and “transformed into a smoke screen that conceals the ‘progress’ of planetary homogenisation; they shall simply be a source of entertainment.” Some 30 or more years after Faye wrote these words, of course, the situation is immeasurably darker than even he predicted, since White identities are no longer even permitted as folklore or entertainment but are rather presented as oppressive and evil.

Faye was clearly, however, a prophetic and perceptive thinker. He foresaw the gradual replacement of genuine political leaders with “regulators,” adding that

the political decisions taken by states are therefore replaced by strategic choices made within the framework of various networks — those of large companies, banking organisations, public or private speculators, etc. All these separate strategies trigger a self-regulation mechanism that allows the System to work towards satisfying its own ends.

While my own tendency is to focus on “known actors,” by which I mean decision-makers and influencers rather than action in the abstract, Faye’s conceptualization of overlapping strategies makes it easier to understand how something like, for example, Jewish influence can seemingly persist and perpetuate “in the open.”

If I could make one minor criticism of this collection of essays, it would simply be that I would have liked to see at least one major essay contributed from the Anglosphere. Truths & Tributes is a translation of a French original, but the English edition may well have benefited from a longer essay from Jared Taylor, and perhaps also from Sam Dickson, who appears to have known Faye quite well and I’m sure could have shared some choice and entertaining anecdotes. I’d also have enjoyed reading a perspective from Daniel Friberg, who appears to have put in considerable work over the years in bringing Faye to English-speaking audiences. Alas, these perhaps can be relayed at a later time, maybe even in a further volume. Certainly, I do not believe we have heard the last word on Faye.

My final thoughts in closing this review are that I believe we could all benefit from adopting the attitude of this lively Frenchman, because even if we might disagree with some of his ideas, there is little doubting the benefits of embracing his contemporary Heraclitism of “innovative mobility.” For Faye, our situation is ever-changing and dynamic, and if we have any hope of meeting that challenge then we too must respond with energy, speed, and even joy, no matter how dark the context. Although his last book was very dark indeed, I hope Faye was able to find some of this joy in his final days. I leave the final word to Pierre Magué:

In a replete and slumbering France, Guillaume Faye was the one to raise the alarm, never worrying about whether or not it was a suitable time to do so, whether he risked interrupting idle chatter and academic speeches. … Such is the characteristic of prophets.

I only read one of the works of Benoist “On being a pagan”, I don’t how representative it is of his broader corpus but I found it incomprehensible. It basically boiled down to “paganism is whatever I like” and I found his “logos v mythos” dichotomy to be dumb, The noise was quite large compared compared to the signal.

Ive read of Faye’s “Archeofuturism” and “Sex and Deviance” and found them found to be very clear, creative & original. The writing is leaps and bounds better then Benoist.

I might have a unclear picture, maybe Benoist’s writing improved or the english translation was poor. If what Steuckers said is true on what happened at GRECE it is very unfortunate that Faye was sidelined.

https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/2021/01/29/gamestop-stocks-robinhood-reddit/ Move over “Occupy Wall St lol!

My wife and I were standing right behind David Duke at the 2006 Amren Conference when Duke was questioning Faye and Michael Hart got quite angry and stormed out of the room. Very interesting moment. I will never forget it.

Sad to see one of our own, who was a champion, expire. What I learned when I was somewhere around 16 years old –due to reflections with my grandfather– is that sometimes it is most pertinent to have an intelligent child under your wing. If you go through life’s cycle with a few of the noted youngsters listening to hx about our own City States, Europeans and the Dark Continent, there’s a chance they may become soldiers of enlightenment and open communique.

Anyone who has studied Alain de Benoist’s face will immediately recognize the crypto-Jew.

Crypto-Jews are 1000 times more cancerous because we don’t recognize their true identity.

Agree 100 percent.

In pictures of the older Alain de Benoist he does indeed look somewhat Jewish, but definitely not in pictures of his as a young man:

https://doorbraak.be/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/Alain-de-Benoist.jpg

Keep in mind that the French are a mixture of Cro-Magnons, Alpines, Mediterraneans and Germanics and that Mediterraneans are not always clearly distinguishable from Jews. Besides, in France a name with “de” indicates nobility and thus excludes Jews.

So, then is Mozart, Grieg, Michel Angelo, vivaldi and shakespeare also crypty jews.

I mean if you gonna make a racial judgement based on looks how peoples noses look and the like then look at these famous whites defining white history in many ways.

And people like Truffeat who was maybe half jewish, is he a problem?

I certainly know there are half jews or whatever that are anti white.

And if those famous people did have jewish heritage of some kind I would assume it to be from non semotic and non african kind (i.e. 100 % white Israelites, not mixed with semites or subsaharian africans, marrying white Christians).

Mozart, Grieg, Michel Angelo, vivaldi and shakespeare do not look crypto-Jews.

Have you seen the picture of Mozart with brown hair a small oil painting that was the closest to how he look according to his sister (ok I read that in a book published by a jewish company). But he had a “distinguished” nose.

Same for Grieg, look at the photo taken from the side of him.

And Michel Angelo also, the nose!

Vivaldi, the nose (look at the charicature on wikipedia).

But else how you gonna see if anyone is partly jewish especially if they are 100 % white jews that part of their heritage. And of course this would only have been part of their heritage if so is the case, all of them were christians and so were their parents and supposedly grandparents. Also Vivaldi was a pries so…

Again maybe these are “roman” noses, but I am not like really aware of the difference.

So who knows.

It’s just I assume maybe what people have historically those who racist towards jews claimed that many of them have. And of course they have, most of them their foreskin cut of.

And the Kellogs dude who made americans do it, do you think he was part jewish and did it as way to make it harder to identify jews? I CERTAINLY THINK THIS IS THE CASE.

SO YANKEEDDOOOODELIDOOS Yankees USA Christian whites stop cutting off foreskins it’s not for us Christians it’s most likely wopeedoo a FRAUD.

Yes part of your dick has been cut off as a jew fraud.

Again mabe it doesn’t make a huge difference. BUT THERE ARE NO HYGIENE REASONS THESE DAYS WE HAVE RUNNING WATER INVENTED BY THE WHITE MAN!!

There’s more to physiognomy than nose.

On France being invaded by Moslems, see

https://big-lies.org/hexzane527/2016-06-06-which-european-countries-will-be-muslim-controlled.html

After reading some of Mr. Faye’s writings, I concluded that we are no longer able to work through the existing power structures to save our nation-states and cultures. I concluded that we can only buy time, nothing else, by doing so. Now, watching events unfold, I am often reminded of a disturbing quote from Mr. Faye, which I am paraphrasing, perhaps somewhat poorly:

“When you are forced to choose between extinction and violence, the only morally correct choice is violence.”

This is a deeply troubling insight. It leaves us on a sandbar at low tide in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean. No one wants to engage in any literal battle. Yet no one wants to see their world drowned. And there is nowhere to which to flee.

When I look this reality full in the face, I greatly regret having procreated.