Religion, Race, and Ethnicity in Greco-Roman Antiquity New Perspectives on The Lordship of Jesus, Judaism, and the “Truthiness” of Christianity, Part Three

The “Truthiness” of Christianity

In short, Miller “challenges the classic conception of what many regard as the most sacred narrative of Western civilization, namely, that the New Testament stories of Jesus’ resurrection provided alleged histories variously achieving credibility among their earliest readers.” Instead, he provides “the first truly coherent case that the earliest Christians comprehended the resurrection narratives of the New Testament as instances within a larger conventional rubric commonly recognized as fictive in modality.” Modern scholarship, by contrast, mistakenly assumes that these texts were intended to present “a credible, albeit extraordinary account of an historical miracle.” On that assumption, one may then approach the question “from one of two polarized loci: (1) with a faith-based interest in honoring (defending) the most sacred tenet of Christianity; (2) with an atheistic interest to disprove the claims of orthodox Christian doctrine.” Both positions are unsound. The first thesis mistakenly supposes that gospel writers proposed the resurrection of Jesus as a historical reality; the second, antithetical, possibility is that the narrative was peddled as an early Christian hoax. In dialectical terms, Miller advances an “authentic synthesis (tertium quid): the early Christians exalted the leader of their movement through the standard literary protocols of their day, namely, through the fictive, narrative embellishment of divine translation.”[i]

It should be obvious that a sincere, honest response to Miller’s investigation by Christian nationalists such as Stephen Wolfe will demand “a fearless, rational, unwavering commitment to the pursuit of truth.”[ii] Unfortunately, Christians, generally, appear ill-equipped to meet this intellectual challenge. Faith-driven presentations of the gospel resurrection tales seem historically plausible only so long as one’s audience knows nothing of their classical literary provenance. The quarantine protecting the New Testament resurrection stories from exposure to their ancient cultural analogues is unlikely to be lifted anytime soon.

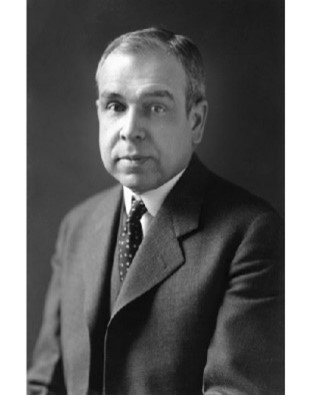

Given Wolfe’s personal preference for the work of older theologians, he has been isolated from critical currents in contemporary New Testament scholarship. On social media, Wolfe has expressed admiration for the work of the early twentieth-century Orthodox Presbyterian scholar, J. Gresham Machen (1881–1937). My guess is that Machen has influenced Wolfe’s understanding of the twin “supernatural truths” which upon which his case for Christian nationalism is grounded: “Jesus is Lord” and “Christianity is the true religion.” In 1921 Machen published a study entitled The Origins of Paul’s Religion. There, he argued that the truth of Christianity was to be found in a study of its origins. Machen acknowledged Jesus as the Founder of Christianity but, because He Himself wrote nothing and “the record of his words and deeds is the work of others,” Machen turned to the testimony of Paul as “a fixed starting point in all controversy.” As Paul was such a central figure in the early history of the Jesus movement, Machen was confident that if one could “explain the religion of Paul … you have solved the problem of the origin of Christianity.”[iii]

Gresham Machen

According to Machen, the religion of Paul “was something new.” His mission to the Gentiles “was not merely one manifestation of the progress of oriental religion, and it was not merely a continuation of the pre-Christian mission of the Jews.” Certainly, “the possession of an ancient and authoritative Book” was “one of the chief attractions of Judaism to the world of that day.” Authority in religion was in short supply. Paradoxically, however, “if the privileges of the Old Testament were to be secured … the authority of the Book had to be set aside. The character of a national religion was … too indelibly stamped upon the religion of Israel.” At best, Gentile converts could “only be admitted into the outer circle around the true household of God.” For Paul, Machen declares, Gentile freedom (i.e., from the law) “was a matter of principle.” This principle had, of course, been “anticipated by the Founder of Christianity, by Jesus Himself.” But, if so, the doctrine of Gentile freedom was based “upon what Jesus had done, not upon what Jesus, at least during His earthly life, had said.” It was unclear what He intended with respect to the universality of the gospel. The “instances in which He extended His ministry to Gentiles are expressly designated in the Gospels as exceptional.” Certainly, as far as his disciples were concerned, “Gentile freedom, and the abolition of special Jewish privileges, had not been clearly established by the words of the Master.” This meant that there was “still need for the epoch-making work of Paul.”[iv]

Machen contends that Paul’s distinctive achievement was not the geographical expansion of the Church. Seas or mountains were not “really standing in the way of the Gentile mission.” Instead, it was “the great barrier of religious principle.” Paul “overcame the principle of Jewish particularism in the only way in which it could be overcome; he overcame principle by principle.” The real apostle to the Gentiles, Machen believed, was Paul the theologian, not Paul the practical missionary. It was his achievement to exhibit “the temporary character of the Old Testament” by enriching the historical, logical, and intellectual understanding of the death and resurrection of Jesus. Consequently, “Gentile freedom, and the freedom of the entire Christian Church for all time, was assured.”[v]

Machen declares that, by convincing others, Jews, and Gentiles alike, that Jesus is Lord, Paul compelled the religion of Israel to go forth “with a really good conscience to the spiritual conquest of the world.” Henceforth, “when Christian missionaries used the word ‘Lord’ of Jesus, their hearers knew at once what they meant. They knew at once that Jesus occupied a place which is occupied only by God.” In the final chapter of his book, Machen defends “the historical character of the Pauline message.” The religion of Paul, he concludes, “was rooted in an event … the redemptive work of Christ in his death and resurrection.” It was based on “an account of something that had happened … only a few years previously.” The facts of that event, the death and resurrection of Jesus, “could be established by adequate testimony,” Machen writes. Moreover, “the eyewitnesses could be questioned, and Paul appeals to the eyewitnesses in detail” (cf., 1 Cor. 15:3-8). He staked everything on the truth of what he said about Jesus’ crucifixion, death, and resurrection. Machen poses the issue in uncompromising terms: If Paul’s account of that event “was true, the origin of Paulinism is explained; if it was not true, the Church is based upon an inexplicable error.”[vi]

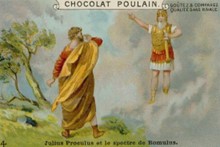

Richard C. Miller’s mimetic criticism of the gospel resurrection narratives presents defenders of Machen’s Christian apologetic, such as Stephen Wolfe, with a stark choice. If the Resurrection of Jesus was, as a matter of fact, just one among many classical fictive narratives of divine translation, in what sense (if at all) can one still proclaim that “Jesus is Lord” and that “Christianity is the true religion?” Neither Paul’s nor Machen’s appeal to “eyewitness” testimony will be sufficient to close the case. That possibility has been foreclosed by Miller’s detailed examination of the “eyewitness” tradition that became “the political protocol in the consecration of those most supremely honored in Roman government” during the Julio-Claudian dynasty.[vii]

The legendary example of Julius Proculus, the alleged “eyewitness” to the post-mortem appearance of Romulus, contributed to the “senatorial tradition of the eyewitness to the apotheosis of the Roman emperors” between 27 BC and 284 AD. The chief historians of the period typically devoted considerable space to the tale. The “senators (as an act of consecration), plebes, and successors assigned glory and deification to a deceased emperor through the process of formal “eyewitness” testimony to the monarch’s translation.” For example, following the death of Caesar Augustus, “the Roman senators carried an effigy of his body in grand procession to the Campus Martius, the location where Romulus achieved apotheosis.” In accordance with the structured requirements of the translation fable, this “public funeral did not involve the actual corpse of the emperor, but a substituted wax effigy.” According to tradition, “the witnesses must not find any charred bones, once the pyric flames have gone their course.” The scenario also provided for a prominent eyewitness “who took oath that he had seen the form of the Emperor on its way to heaven, after he had been reduced to ashes.”[viii]

One suspects, however, that Anglo-Protestant evangelicals are unlikely to be impressed by such scholarly skepticism as to the historicity of the Resurrection of Christ Jesus. Faith-based conservative evangelicals still condemn as a “heretic” any supposed Christian questioning—what Stephen Wolfe might call the “supernatural truth” of—the futurist eschatology outlined in various creeds. Accordingly, Pastor Douglas Wilson (whose Canon Press publishes Wolfe’s book on Christian nationalism) recently joined many other religious leaders in signing an open letter which calls upon Gary DeMar (head of the American Vision ministry) to recant his alleged refusal to affirm “the future, bodily, and glorious return of Christ, a future, physical, and general resurrection of the dead, the final judgement of all men, “and the tactile reality of the eternal state.” DeMar was accused of denying “critical elements of the Christian faith” by declining to label full preterism as “heretical”[ix] (preterists hold that all of God’s promises to Old Covenant were fulfilled at the time of the destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 70 AD).[x]

But what is “truth?” A correspondence theory of truth holds that a statement “is true if it corresponds to the facts; and, conversely, if it corresponds to the facts, it is true.” It would be difficult to maintain that any of the propositions put to Gary DeMar by his critics satisfies a correspondence theory of truth. On the other hand, the scholarly field of “mimetic criticism” lends credibility to a coherence theory of truth. Here, truth is defined “as a relation not between statement and fact, but between one statement and another.” On this view, “no actual statement … is made in isolation: they all depend upon certain presuppositions or conditions and are made against a background of these.”[xi] A practitioner of mimetic criticism such as Richard C. Miller might agree, therefore, that it is true that Romulus, Caesar Augustus, and Jesus Christ were all resurrected (or translated) from the dead through exaltation to divine status. But would Wolfe or Pastor Wilson concede that Jesus’ resurrection, along with the Second Coming of Christ, are truths anchored, not in history as it happened, but in the realm of myth, legend, or fiction? If not, creedal Christianity is characterized, at best, less by its demonstrable “truth” than by its “truthiness.”

Was Paul a Jew, an Israelite, or a Christian?

It may still be, however, that the religion of Jesus and Paul was true in another, pragmatic, sense. Miller hints at this issue when he observes that “the mythic dimensions of cultural stories, rather than being the mere arbitrary product of a supposed whimsical human imagination, arise out of the innate anthropological, psychic disposition of the peoples who produce and value them.” In other words, myths “arise out of the subconsciously discerned survival and adaptive needs” of individuals and groups in relation to their “social and physical environment.[xii] Robyn Faith Walsh more pointedly observes that Paul was “constructing a myth of origins for his audience.” Many of his rhetorical strategies were “constituent of Paul’s larger project of religious and ethnopolitical group-making.” She characterizes Paul as “a religious and ethnopolitical entrepreneur” for whom “ethnicity is not a blunt instrument; it is an authoritative frame for achieving cohesion among participants, and one that calls for a sense of shared mind and practice.” Accordingly, Paul “proposes that God’s pneuma is intrinsically shared among his addressees, binding them together.”[xiii] On a purely pragmatic view, Paul’s ethnotheology became true or false depending upon whether it worked. Of course, any assessment of the degree of practical success achieved by Paul and the Jesus movement turns on our understanding of the goals they pursued.

Practitioners of mimetic criticism, such as Walsh, Miller, and Dennis R. MacDonald, locate New Testament writers within the discursive realm of Greco-Roman literature.[xiv] They show that the work of Paul and the gospel writers functioned as a strategy for constructing new, or resurrecting old, social identities, aiming in the first instance at Hellenized Jews and God-fearing Gentiles in both Judea and, more broadly, throughout the Dispersion. Other scholars have moved beyond literary analysis to examine the geopolitical breadth of the movement’s aims as well as the deep historical roots of its ethno-religious identity. Together, both approaches effectively undermine J. Gresham Machen’s claim the “universalism of the gospel” was incarnate in both Jesus, whose redemptive work made possible the Gentile mission, and Paul, who discovered the true, theological significance of Gentile freedom.[xv]

Certainly, Machen found it difficult to deny that Jesus attached an ethnic identity to the God of Israel. He conceded that Jesus’ disciples would not have been “obviously unfaithful to the teachings of Jesus if after He had been taken from them they continued to minister only to the lost sheep of the house of Israel.”[xvi] Closer to our own day, another prominent Pauline scholar, James Dunn acknowledged that Jesus recognized the covenantal boundary around Judaism by “his choice of twelve to be his closest group of associates, with its obvious symbolism (12 = the twelve tribes)” and in “the picture of the final judgement in terms of the twelve judging the tribes of Israel (Matt. 19:28/Luke 22:30).” But, like Machen, Dunn gives Paul credit for making clear the importance of “Gentile freedom.” Paul brought the universal significance of the gospels into the light of day. He taught that “faith in Christ is the climax of Jewish faith, it is no longer to be perceived as a specifically Jewish faith; faith should not be made to depend in any degree on the believer living as a Jew (judaizing).” [xvii]

But did Paul really refuse to require his Gentile converts to judaize as Dunn claims? This raises an even more fundamental question: What were the goals of Paul and the Jesus movement? Were Jesus and Paul on the same page with respect to those goals? Jesus certainly looked forward eagerly to the imminent end of the age and the promised restoration of the twelve tribes of Israel. He was not alone. “Whether in the diaspora or (however defined) in the homeland,” restoration theology occupied a prominent place in the Jewish mind in the first century. Diaspora Jews may have lived in pleasant and prosperous circumstances but they never “dropped traditional restoration eschatology in favor of a more positive perspective on the dispersion.” In fact, educated Hellenistic Jews regularly portrayed diaspora as exile. At the same time, most believed that “the diaspora would ultimately turn out for the best.” Staples suggests that “exile and diaspora simultaneously serve[d] as punishment for sin and the means for redemption, the greater good brought out of redemptive chastisement.”[xviii] Amidst such a tense but expectant socio-cultural atmosphere, Jesus’ direction to his disciples to serve the lost sheep of Israel launched an apocalyptic, ethno-religious movement aiming to resurrect the twelve tribes of Israel.

But how could Paul’s mission to the Gentiles serve the goals of a restorationist theology focused on the idea of Israel? The standard Christian answer turns on a reading of Romans 11:25–26. There, Paul suggests that the salvation of “all Israel” will not happen “until the fulness of the Gentiles be come in.” Creedal Christian theologians, such as Manchen and Dunn, interpret such passages as downplaying the specifically, and narrowly, Jewish restoration eschatology in favour of an apocalyptic vision embracing the whole of humanity. Dunn, for example, writes that Paul’s “apocalyptic perspective … looked beyond the immediacy of the situation confronting his mission and the Israel of God.” In doing so, he “set the local or national crisis of Israel’s identity within a cosmic framework.” The coming Kingdom of God “had a universal significance.” Like Machen, Dunn maintains that Paul was against “Jewish privilege” and in favour of Gentile freedom and equality in the eyes of God. “No national or ethnic status, or we may add, social or gender status (cf. Gal. 3:28), afforded a determinative basis for or decisive assurance of God’s favour.” That universalist principle applied not just to Israel but to the world at large.[xix]

Paula Fredriksen and Derek Lambert of MythVision

Paula Fredriksen takes issue with this interpretation of Paul’s mission. She flatly rejects any reading of Paul’s letters from which he “emerges as the champion of universalist (‘spiritual’) Christianity over particularist (‘fleshly’) Judaism.” She sets herself in opposition to scholars such as Machen and Dunn for whom “Paul stands as history’s first Christian theologian, urging a new faith that supersedes or subsumes the narrow Ioudaϊsmos of his former allegiances.” In her view, far from superseding his Jewish identity, Paul preached “a Judaizing gospel, one that would have been readily recognized as such by his own contemporaries.” His “core message to his gentiles about their behavior was not ‘Do not circumcise!’ Rather, it was “Worship strictly and only the Jewish god.” He required Gentile “ex-pagans” to abandon the “lower gods” of their kinfolk. They would retain their native ethnicity but live, in a certain sense, outside and apart from their co-ethnics. Having received the holy spirit, these Gentiles “were to live as hagioi, ‘holy,’ or ‘sanctified’ or ‘separated-out’ ethne, according to standards of community behavior described precisely in ‘the Law.’” But he did not expect, much less require, Gentile males to undergo circumcision. On the other hand, he nowhere “says anything about (much less against) Jews circumcising their own sons. … He opposed circumcision for gentiles, not for Jews.” Israel must remain Israel. God’s coming Kingdom “was to contain not only gentiles, but also Israel, defined as that people set apart by God by his Laws (e.g., Lev 20.22–24).”[xx]

Paul, according to Fredriksen, “maintains and nowhere erases the distinction between Israel and the nations.” At the same time, however, his rhetoric erases “the distinctions between and among ‘the nations’ themselves.” The nations or “ethnē function as a mass of undifferentiated ‘foreskinned’ idol-worshippers (if outside the movement) or of ‘foreskinned’ ex-idol-worshippers (if within).” The God of Israel is also the god of other nations as well. “But the nations by and large will know this only at the End.” And the point to bear in mind here is that “Paul, a member of a radioactively apocalyptic movement, sees time’s end pressing upon his generation now, mid-first century.”[xxi] Moreover, “for Paul, the more intense the pitch of apocalyptic expectation, the greater the contrast between Israel and the nations.” It was this “ethnic-theological difference between Israel and the nations, the nation’s ignorance of the true god, is what binds all of these other ethnē together in one undifferentiated mass of lumpen idolators.” At the End, “this sharp dichotomy is resolved theologically, but not ethnically: Israel remains Israel, the nations remain the nations (cf. Isa 11.10; Rom 15.10).”[xxii]

According to Paul’s “eschatological arithmetic” the world consists of the seventy nations listed in the Table of Nations (Genesis 10) and the twelve tribes of Israel. At the End, all “will, somehow, receive Christ’s pneuma” (spirit).” Gentiles-in-Christ (who Fredriksen describes as “eschatological Gentiles”) will “rejoice with saved Israel, but they do not ‘become’ Israel. … Even eschatologically—that is, ‘in Christ’—Jews and Gentiles, though now in one ‘family’ are not ‘one’.”[xxiii] Yet, paradoxically, while Paul’s ethnē-in-Christ are not-Israel, they are not only “enjoined to Judaize to the extent that they commit to the worship of Israel’s god alone and eschew idol-worship,” they “must behave toward each other in such a way that they fulfill the Law.” For Paul, “the only good gentile is a Judaizing gentile.”[xxiv]

Clearly, there are unbridgeable differences between Fredriksen, a convert to Judaism, on the one hand, and Anglo-Protestants such as Machen, Dunn, and Pastor Doug Wilson, on the other. But, on one issue, at least, they all agree: both Jesus and Paul must be considered failed prophets. Fredriksen is confident that “the historian and theologian know something that the actors in this [eschatological] drama could not; namely, that Jesus Christ would not return to establish the Kingdom within the lifetime of the first (and, according to their convictions, the only) generation of his apostles.”[xxv] Unsurprisingly, atheistic/agnostic scholars such as Bertrand Russell, Bart Ehrman, and Richard C. Miller share that view.

Consequently, few scholars of any stripe, Jewish, Christian, or non-believer, will appeal to a pragmatic theory of truth to uphold the truth of the eschatology of the first-century Jesus movement. Fredriksen even expresses surprise that Paul remained convinced even at mid-century that the End would come within his own lifetime: How, after a quarter-century delay, could he reasonably assert that ‘salvation is nearer to us now than when we first believed?’”[xxvi]

Despite Fredriksen’s incredulity, Paul’s expectations turn out to have been reasonable on the assumption that he looked forward to the end of the Old Covenant age, not the end of the world. Tom Holland, to cite but one prominent scholar, suggests that both Jesus and Paul framed their eschatological expectations as a New Exodus. Paul insisted “that Israel’s experience of Exodus whether from Egypt or Babylon was only a rehearsal of the forthcoming eschatological salvation.” Israel was separated from God and “shut up under Sin,” refusing to heed the message of the gospel. Israel herself “was now behaving like Pharoah” in opposing the Exodus of the people of God. In the mimetic character of that New Exodus, Paul could hardly be surprised that forty years would elapse before judgement was visited upon Old Covenant Israel and “the holy city, new Jerusalem” came “down from God out of heaven” (Rev. 21:2).[xxvii] And, remembering the death of Moses, Paul must have known that he might not live to see that day (Deut. 34:1-8). In other words, prima facie, a pragmatic case can be made for the credibility of the eschatology foreshadowed in the religion of Paul. Certainly, the covenant eschatology of Don K. Preston and other preterist biblical scholars does just that.[xxviii]

The work of Jason A. Staples on Paul and the resurrection of Israel lends additional support to the biblical truth of both restoration theology and covenant eschatology. It is important here to note the difference between Staples’ thesis and Fredriksen’s claim that both Jesus and Paul were working “within Judaism.” Fredriksen has no doubt that Paul was “an ancient Jew, one of any number of whom in the late Second Temple period expected the end of days in their lifetimes.” She is no less confident that, in Paul’s mind, “whether ‘now’ (mid-first century) or in the (impending) End time, ‘Israel’ is the Jews.”[xxix] Staples calls both propositions into question. He points out that Paul prefers “to identify himself as ‘of the nation of Israel, of the tribe of Benjamin’ (Phil 3:5; Rom 11:1; 2 Cor 11:22) rather than using the more generic term ‘Jew’. In addition, Paul frames his ministry in ‘new covenant’ language, suggesting the centrality of the restoration of all Israel to his gospel.”[xxx]

Paul’s “new covenant” theology echoes Jeremiah 31:31 but, Staples reminds us, “Jeremiah’s prophecy primarily concerns the reconstitution of all Israel—that is, that both Israel and Judah will be restored by means of God’s writing the law on their hearts.” This implies, however, that “the covenant will be madeonly with Israel and Judah,” given that Gentiles are not mentioned in the prophecy. But it turns out “that faithful Gentiles (those with ‘the law written on their hearts’; see Rom 2:14–15) are the returning remnant of the house of Israel, united with the faithful from the house of Judah (cf. the ‘inward Jews’ of Rom 2:28–29).” It matters not “whether Paul actually imagines that all redeemed Gentiles are literal descendants of ancient Israelites.” Gentile inclusion was to be the means of Israel’s promised restoration because the seed of the northern tribes was mixed “among the Gentiles—thus God’s promise to restore Israel has opened the door to Gentile inclusion in Israel’s covenant.” Staples cites Hosea 8:8 to sum up the situation: “Israel [the north] is swallowed up; they are now in the nations [Gentiles] like a worthless vessel.”[xxxi]

By means of this process, God has provided for the salvation of the Gentiles by scattering the northern tribes “among the nations only to be restored.” By this means, the new covenant also “fulfills the promises to Abraham that all nations would be blessed, not ‘through’ his seed (i.e., as outsiders) but by inclusion and incorporation in his seed (Gal 3:8).” These faithful Gentiles need not, however, “become Jews (that is, Judah) in order to become members of Israel—rather they have already become Israelites through the new covenant.”

[i] Richard C. Miller, Resurrection and Reception in Early Christianity (New York: Routledge, 2015), 180–182.

[ii] Ibid., 182

[iii] J. Graham Machen, The Origins of Paul’s Religion; The James Sprunt Lectures Delivered at Union Theological Seminary in Virginia, Leopold Classical Library, [Original publication, 1921], 4-5.

[iv] Ibid., 12-15.

[v] Ibid., 17, 19.

[vi] Ibid., 13, 316.

[vii] Miller, Resurrection and Reception, 75.

[viii] Ibid., 66-75.

[ix] “An Open Letter to Gary DeMar of American Vision,”

https://reformation.substack.com/p/an-open-letter-to-gary-demar

[x] See, e.g., Don K. Preston, Who is this Babylon? (Ardmore, OK: JaDon, 2011) and https://bibleprophecy.com/

[xi] W.H. Walsh, Philosophy of History: An Introduction (New York: Harper Torchbooks, 1960), 73, 76.

[xii] Miller, Resurrection and Reception, 104.

[xiii] Walsh, Origins of Early Christian Literature, 37-39.

[xiv] Dennis R. MacDonald, Synopses of Epic, Tragedy, and the Gospels (Claremont, CA: Mimesis Press, 2022). This reference work based on MacDonald’s mimetic criticism provides a comprehensive collection of parallels between New Testament writers and classical Greco-Roman literature. There is no space here to discuss those examples.

[xv] Machen, Origin of Paul’s Religion, 13-14.

[xvi] Ibid., 15.

[xvii] Dunn, Partings of the Ways, 114, 133.

[xviii] Staples, The Idea of Israel, 204, 208.

[xix] James D.G. Dunn, The New Perspective on Paul, Revised Edition (Grand Rapids, MI: William B.Eerdmans, 2008), 328-329.

[xx] Fredriksen, Paul, 108, 111-113.

[xxi] Paula Fredriksen, “Paul, Pagans and Eschatological Ethnicities: A Response to Denys McDonald,” (2022) 45(1) Journal for the Study of the New Testament 51, at 56.

[xxii] Fredriksen, Paul, 114-116.

[xxiii] Ibid., 88; Matthew Thiessen and Paula Fredriksen, “Paul and Israel,” in B. Matlock and M. Novenson (eds.), The Oxford Handbook of Pauline Studies 365, at 378.

[xxiv] Fredriksen, Paul, 117, 125.

[xxv] Paula Fredriksen, “Judaism, the Circumcision of Gentiles, and Apocalyptic Hope: Another Look at Galatians 1 and 2,” (1991) 42(2) Journal of Theological Studies 532, at 533.

[xxvi] Ibid., 533 n.4.

[xxvii] Tom Holland, Contours of Pauline Theology: A Radical New Survey of the Influences on Paul’s Biblical Writings (Fern, Scotland: Mentor, 2004), 211.

[xxviii] Don K. Preston, “We Shall Meet Him in the Air:” The Wedding of the King of Kings! (Ardmore, OK: JaDon, 2010).

[xxix] Paula Fredriksen, “What Does it Mean to See Paul ‘within Judaism’?” (2022) 141(2) Journal of Biblical Literature 359, at 379; Fredriksen, “Reply to McDonald,” 60 (emphasis added).

[xxx] Staples, “What Do the Gentiles Have to Do with ‘All Israel,’” 378.

[xxxi] Ibid., 380-381.

Interesting section: Fredriksen (who converted to Judaism) proposes that Paul wanted Christians to be Judaizers–not Jews but sympathetic to Judaism and engaging in Jewish rites, etc. In other words, Paul wanted to make the new religion sympathetic to Judaism–a Jewish agenda.

Paula Fredriksen … flatly rejects any reading of Paul’s letters from which he “emerges as the champion of universalist (‘spiritual’) Christianity over particularist (‘fleshly’) Judaism.” She sets herself in opposition to scholars such as Machen and Dunn for whom “Paul stands as history’s first Christian theologian, urging a new faith that supersedes or subsumes the narrow Ioudaϊsmos of his former allegiances.” In her view, far from superseding his Jewish identity, Paul preached “a Judaizing gospel, one that would have been readily recognized as such by his own contemporaries.” His “core message to his gentiles about their behavior was not ‘Do not circumcise!’ Rather, it was “Worship strictly and only the Jewish god.” He required Gentile “ex-pagans” to abandon the “lower gods” of their kinfolk. They would retain their native ethnicity but live, in a certain sense, outside and apart from their co-ethnics. Having received the holy spirit, these Gentiles “were to live as hagioi, ‘holy,’ or ‘sanctified’ or ‘separated-out’ ethne, according to standards of community behavior described precisely in ‘the Law.’” But he did not expect, much less require, Gentile males to undergo circumcision. On the other hand, he nowhere “says anything about (much less against) Jews circumcising their own sons. … He opposed circumcision for gentiles, not for Jews.” Israel must remain Israel. God’s coming Kingdom “was to contain not only gentiles, but also Israel, defined as that people set apart by God by his Laws (e.g., Lev 20.22–24).”[xx]

Paul, according to Fredriksen, “maintains and nowhere erases the distinction between Israel and the nations.” At the same time, however, his rhetoric erases “the distinctions between and among ‘the nations’ themselves.” The nations or “ethnē function as a mass of undifferentiated ‘foreskinned’ idol-worshippers (if outside the movement) or of ‘foreskinned’ ex-idol-worshippers (if within).” The God of Israel is also the god of other nations as well. “But the nations by and large will know this only at the End.” And the point to bear in mind here is that “Paul, a member of a radioactively apocalyptic movement, sees time’s end pressing upon his generation now, mid-first century.”[xxi] Moreover, “for Paul, the more intense the pitch of apocalyptic expectation, the greater the contrast between Israel and the nations.” It was this “ethnic-theological difference between Israel and the nations, the nation’s ignorance of the true god, is what binds all of these other ethnē together in one undifferentiated mass of lumpen idolators.” At the End, “this sharp dichotomy is resolved theologically, but not ethnically: Israel remains Israel, the nations remain the nations (cf. Isa 11.10; Rom 15.10).”[xxii]

According to Paul’s “eschatological arithmetic” the world consists of the seventy nations listed in the Table of Nations (Genesis 10) and the twelve tribes of Israel. At the End, all “will, somehow, receive Christ’s pneuma” (spirit).” Gentiles-in-Christ (who Fredriksen describes as “eschatological Gentiles”) will “rejoice with saved Israel, but they do not ‘become’ Israel. … Even eschatologically—that is, ‘in Christ’—Jews and Gentiles, though now in one ‘family’ are not ‘one’.”[xxiii] Yet, paradoxically, while Paul’s ethnē-in-Christ are not-Israel, they are not only “enjoined to Judaize to the extent that they commit to the worship of Israel’s god alone and eschew idol-worship,” they “must behave toward each other in such a way that they fulfill the Law.” For Paul, “the only good gentile is a Judaizing gentile.”[xxiv]