Introduction

In my last article (“Jewish Bolsheviks and Mass Murder: Rozalia Zemliachka and the Jews Responsible for the Bloodbath in Crimea, 1920”), I described a group of Communist Jews and the slaughter they perpetrated in the early years of Bolshevik rule in Russia. Over the thirty-five years that spanned the rule of Lenin and Stalin, there were hundreds of similar massacres, carried out by various delegations of Cheka-OGPU-NKVD officers (with significant Jewish representation or even outright leadership), operating in every region of the USSR. These massacres cry out for more attention, and I hope to write about more of them. In the meantime, however, I will describe three depraved Jewish executioners, each of them richly deserving infamy and execration: Mikhail Vikhman, Revekka Plastinina-Maizel, and Isai Berg. Vikhman was a leading Cheka commissar in Odessa and Crimea in 1919–1921, where he personally shot hundreds of victims, including some of the highest rank. (His later career features an exquisite irony.) Plastinina-Maizel was a Party official who barbarically murdered thousands in the Far North of Russia together with her consort, a mad Cheka official. She later enjoyed a career at the highest level of the Soviet judiciary, a fine commentary on the perversities of Soviet society. Berg, a leading NKVD official in Moscow and executioner in the Great Terror, already boasts some notoriety among anti-Communists because he pioneered the homicidal gas van, which was meant to help him in his regular job: organizing nearly twenty thousand executions at the Butovo killing grounds in 1937–1938. These three Jews alone are responsible for the death of over twenty thousand people, and their names should be at least as well-known as Eichmann or Mengele, and for better reasons.

MIKHAIL VIKHMAN

Mikhail Vikhman was born in 1888, in or near Astrakhan on the Caspian Sea. His father Moisey was a dealer in fish. Mikhail graduated from the Realschule in Astrakhan in 1907, then worked as an electrician until he was conscripted in 1912. He served in a sapper battalion,[1] fought in the World War, and won the St. George Cross (4th degree). When the Revolution came, he suddenly ascended to positions of power, initially chief of police in Tsaritsyn (Stalingrad).[2] By 1918 he had joined the Bolsheviks, become a Chekist, participated in suppressing a Cossack uprising, and, as commander of the 1st Red Partisan Regiment, fought in Ukraine against various anti-Bolshevik forces. In the spring of 1919, he became a leader of the Cheka in Odessa, the third-largest city in Ukraine. The erstwhile sapper corporal now had the power of life and death over nearly half a million people. (The city was heavily Jewish, and its Cheka was too.) Here he won fame, not as a wise administrator or promoter of the common good, but as a bloodthirsty mass murderer. Sergei Melgunov in The Red Terror in Russia tells us that Vikhman employed six executioners but “would go into the cells, and slaughter prisoners for his personal pleasure.”[3] In the summer of 1919 forty or fifty prisoners were shot every night, and former White officers were killed “by chaining them to planks and then pushing them very slowly into furnaces . . .”[4] One source states that Vikhman shot over 200 people during his time in Odessa, including the former police chief Baron Sergei Vasilyevich van der Hoeven (1865–1919) and the rector of the Novorossiysk University, Sergei Levashov.[5] Melgunov gives another story, sadly typical of the era:

. . . there is on record a case where, on the lid of a coffin slowly opening and emitting a cry of “My comrades, I am still alive!” a telephone message was sent to the Che-Ka, and elicited the reply, “Settle him with a brick,” whilst a further appeal to the head of the Che-Ka himself [Vikhman] called forth the jest: “We are to requisition the best surgeon in Odessa, I suppose?” and finally a Che-Ka employee had to be dispatched to the scene, to shoot the victim a second time with a revolver.[6]

Vikhman seems to have worked in Odessa through part of the year 1920, but in the spring of 1921 he became the chairman of the Crimean regional Cheka.[7] The Red Army had recently conquered Crimea, and Bolshevik forces under the leadership of two repulsive Jews, Bela Kun and Rozalia Zemliachka, had subjected the peninsula to a horrific scourging. Now Vikhman, another remorseless Jew, headed all Cheka forces in the peninsula, and the killing proceeded. Remnants of the White forces had taken to the hills to wage guerrilla warfare (as much to survive as to resist Communist rule) and Vikhman organized forces to wipe them out; captives were liquidated. The Communists judged many others deserving of death, and Vikhman lent his hand and his Mauser to the task. Among others, he shot the former Ukrainian ministers Alexander Ragoza and Komorny. Years later he stated that in Crimea he personally shot “many hundreds” of “enemies of Soviet power … the exact number of which is written on my combat Mauser and combat carbine.”[8]

But there was trouble: the Crimean Bolshevik Party Committee became upset with Vikhman’s haughty manner. They charged him with arresting Party members and defiance of Party authorities. He was removed from his position and sent to the Caucasus, where he worked in the Stavropol Provincial Cheka. By the end of 1921, however, the Party expelled him and cashiered him from the Cheka.[9] It was the end of the first phase of his career.

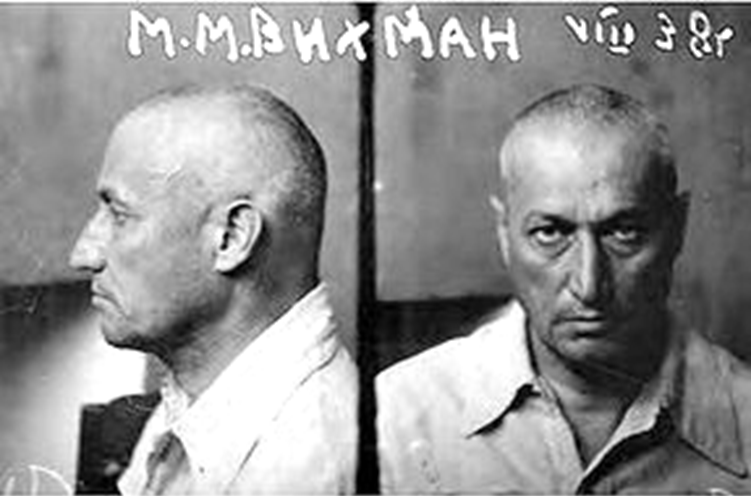

Vikhman returned to Odessa and worked in the administration of the city tram network, quite the fall for the menacing, all-powerful Cheka executioner. Before long, however, he gained readmittance to the Party and even the Cheka. After 1928 he worked in various mid-level capacities for the OGPU (successor organization of the Cheka), in Kharkov (Ukraine) and the Caucasus. He participated in suppressing peasant revolts, headed the Chernigov city department OGPU, and won the award “Honorary Worker of the Cheka-OGPU” (1932). By the year 1938 he was working in Vinnytsia as deputy head of the NKVD militia. Then there came a knock at the door. It was July 8, 1938, the height of the Great Terror, the absolute peak of the decades-long repression, and Stalin was beginning to liquidate the liquidators. Genrikh Yagoda, Jewish head of the NKVD, had been shot in March, and thousands more secret police perished in the next few years. Now it was Vikhman’s turn: the secret police searched his house, seized a cache of weapons, and took him to Lukyanivska prison in Kiev.

The Party was carrying out a major purge of the Ukrainian NKVD: Vikhman’s former boss, the Jewish head of the NKVD in Ukraine, Izrail Leplevsky, had been replaced in January, arrested in April, and shot in July. The new boss, the Russian Alexander Uspensky, had orders to clear out Leplevsky’s men, “who included large numbers of Jewish NKVD operatives.”[10] Hundreds were arrested, but not all: Leplevsky had been tortured during his interrogation by the Jewish NKVD men Lulov and Vizel,[11] and Vikhman now faced a similar experience: he was tortured by the Jews Kogan (Russian form of Cohen) and Ratner.[12] These men beat him mercilessly and forced him to stand continuously for up to four days. (How many people had Vikhman done this to?) By July 17 he gave in and admitted guilt. He was left badly damaged, even crippled, by this treatment.

Vikhman in the hands of Jewish interrogators

Vikhman in the hands of Jewish interrogators

It was an astonishing scene: in twentieth-century Russia, a man named Cohen, descendant of the ancient Hebrew priestly line, interrogating and torturing another Jew, both avowed atheists and ruthless members of the same secret police force, serving a Georgian tyrant ruling over Russia in the name of Marxist socialism![13]

Vikhman, understandably, was outraged that he was subjected to such treatment and appealed to higher authorities. In a letter to a deputy of the Supreme Soviet, he cited his work for the socialist motherland, proudly boasted that he had shot hundreds of the enemies of Soviet rule and appealed to “justice” and “Bolshevik Stalinist truth.”[14] In his desperate straits he suddenly found verities to cling to. In the end he escaped the bullet in the neck: he was sentenced to five years (November 1939), and a few months later the State ordered him released, probably because of his physical deterioration. He spent the next year in a neurological hospital, but eventually resumed work, in the Soviet electric power industry and in a shipbuilding plant in his hometown of Astrakhan. Eventually he retired but had to sell mineral water to supplement his meager pension. He won political rehabilitation in 1956. This was a process in which the state proclaimed some of the people repressed under Stalin innocent and restored them to their rights, including pensions. The courts would look at the evidence and make a ruling, and Vikhman saw his name “cleared” before his death.[15]

One wonders what he thought about it all as he neared the end of his life, the dreams of a socialist paradise, the prestige and power he enjoyed, flashbacks of the deafening crack of his Mauser in the death-cellars, the bitterness of his own arrest and torture. And finally, penury and physical impairment. He wasn’t an intellectual; perhaps he spent little time in reflection, assuaging his grievances by cleaving to the old vision of socialism, the one thing that could make it all seem worthwhile. Like other old Stalinist apparatchiks (even Kaganovich and Molotov)[16] he lived out his life in a threadbare apartment, waiting for the monthly pension check, playing checkers and reading Pravda. He died in 1963.[17]

REVEKKA PLASTININA-MAIZEL

Our second subject is Revekka Plastinina-Maizel. Plastinina was her married name, Maizel her maiden name. She was born in 1886 in Grodno, a typical city of the Pale of Settlement, near the junction of Belarus, Lithuania, and Poland, with a mixed population to match, nearly half Jewish. Her parents were Kivel and Olga; her brothers Moisey and Yakov emigrated to America, and her sister Anna later lived with her children near Revekka in Moscow. In 1904 Revekka joined the underground Russian Social Democratic Labor Party (RSDLP), and a couple years later she helped her cousin Eva, imprisoned for revolutionary activity, escape from Grodno prison.[18] By the year 1909 she was married to Nikandr Plastinina, a Russian revolutionary, and they were living in Switzerland, where Nikandr helped Lenin print his newspaper Iskra. They had a son, Vladimir.[19] They were of that class of professional revolutionaries who spent their time reading, writing articles, “organizing” the workers, and dreaming of the future. Revekka’s father, a lawyer, presumably supported her lifestyle.

Nikandr Plastinina, Vladimir, and Revekka in Geneva 1916

Nikandr Plastinina, Vladimir, and Revekka in Geneva 1916

When the Tsar fell from power, they hurried back to Russia, along with thousands of other exiles. Nikandr’s hometown was Shenkursk in north-western Russia, and that became their base. By January 1918 Revekka became secretary of the Shenkursk City Soviet and in June a member of the Archangelsk Provincial Executive Committee. Archangelsk, on the White Sea, was a much bigger city, the hub of Archangelsk Province. Revekka and Nikandr worked together to establish Bolshevik power, but quite soon an Allied intervention drove the Bolsheviks out of the area. In early August Archangelsk was taken by British and American troops, who drove south as far as Shenkursk. Russian uprisings against the Communists had aided the Allies in both cities; Revekka and other members of the Executive Committee had been seized by the rebels, but Revekka escaped.[20] Revekka and Nikandr then worked as political commissars in the Sixth (Red) Army, which was fighting in that area. In early 1920 Bolshevik forces retook the area and commenced a vengeful and murderous purge, in which Revekka played a leading role. It was a wave of terror very similar to that which took place in Crimea later that year.

Moscow sent a top Cheka official, Mikhail Kedrov, to Archangelsk to “pacify” the area. Revekka left Nikandr and took up with Kedrov, eventually marrying him. Some sort of quarrel had broken out between Nikandr’s family and Revekka, with the result that she ordered the death of his entire family, “whom she crucified in an act of savage revenge.”[21] Apparently, the family were disgruntled when Nikandr and Revekka executed the brother-in-law of Nikandr, and evinced insufficient revolutionary ardor for the liking of Revekka. Sergei Melgunov says that she “repaid petty insults once shown her by her first husband’s family by having that family crucified en masse . . .”[22] Petty insults and lack of revolutionary ardor repaid with mass crucifixion? She was clearly a homicidal maniac, but this was only the start. The result of the family holocaust was that Nikandr fled and took up work elsewhere.[23] He did not escape Stalin, however. He died in a camp after being arrested in 1938.

Kedrov, it seems, was inflicted with hereditary madness (his father died in a lunatic asylum), although he was a highly cultured man from the lower Russian nobility, a musician and doctor. He used to play Beethoven for Lenin in exile before the Revolution.[24] He had three sons with his first wife, one of whom, Igor, became a vicious NKVD interrogator in the 1930s. Now, in March 1920, Mikhail was sent north “as a member of a commission charged with the investigation of crimes perpetrated by White Guard and Allied . . . troops. In effect this was a punitive expedition . . . and it earned Kedrov a reputation for extreme cruelty.”[25] Revekka took full part in this campaign, matching the cruelty and madness of Kedrov, who reportedly had to be confined in a mental hospital afterwards.

Revekka, Mikhail Kedrov and his son Igor

Revekka, Mikhail Kedrov and his son Igor

Party leaders in Moscow placed Revekka on the Archangelsk provincial Revolutionary Committee.[26] She and Kedrov held untrammeled power over the area, and the killing began. White officers who managed to flee later reported that in Arkhangelsk they shot 60-70 people a day. The ancient monasteries of Solovetsky, Kholmogory, Pertominsky were turned into concentration camps, later famous as the dreadful White Sea camps of the Gulag. Kholmogory was set up as a simple extermination center. Thousands were shot in these camps in 1920 alone.[27] Kedrov “had 1,200 White Army officers machine-gunned aboard a barge at Kholmogory, killing half of them . . . whilst his second wife, Rebeka Plastinina-Maisel, drowned 500 refugees and [White] soldiers aboard a scuttled barge …”[28] The two would travel the region aboard their train and “question prisoners from their travelling saloon at railway stations, and then and there shoot the wretches as soon as Rebekah had finished belabouring them, and shouting at them, and attacking them with her fists as . . . she cried hysterically “To be shot! Put them up against the wall!”[29] Another White Russian refugee testified that Revekka “killed eighty-seven officers and thirty-three citizens with her own hand.”[30]

Archangelsk Oblast (Province)

Archangelsk Oblast (Province)

It was not long before the two alarmed even their superiors with their wild excesses. That summer an anti-Bolshevik uprising broke out and they suppressed it with such murderous abandon that they were removed from their posts. Kedrov was reportedly preparing to execute a schoolful of students. Party comrades noted officially that Revekka was a “sick woman” (the same diagnosis applied to Roza Zemliachka after she had descended into a bloody psychosis in Crimea a few months later.)[31] They were not punished, of course, merely reassigned. Kedrov “spent some time in psychiatric care before reemerging to work, just as cruelly, for the Cheka around the Caspian Sea. He retired from the Cheka after the civil war . . .”[32] Revekka presumably accompanied him in his various posts. Eventually they settled in Moscow, near her sister Anna and her family.

Kedrov would not live out his natural life, unlike Revekka. Kedrov had accused the new chief of the NKVD (November 1938), Lavrenty Beria, of being a double agent, and Beria arrested him in November 1939. Kedrov amazingly won an acquittal from the Supreme Court, but Beria simply ordered him shot in October 1941.[33] Revekka fared much better: she ascended to a seat on the Soviet Supreme Court in the same decade.[34] (Other than this, I found no other details of her later life.) She died at sixty in October 1946, and was buried in Donskoye Cemetery in Moscow, which was the site of secret mass burials in the Great Terror.[35] The Russian land breathed a little freer that winter.

Isai Berg

Isai Davidovich Berg was born in Moscow in 1905.[36] In the early 1920s he served in the Red Army. By 1926 he had joined the political police and completed the course at the OGPU School, after which he joined the OGPU border guards. In 1930 he joined the Communist Party, then worked undercover in several Moscow area factories, monitoring the attitudes and speech of the workers for his OGPU superiors. In 1932-35 he headed the Shchyolkovo District Department of the OGPU, just northeast of Moscow. In 1935-36 he worked in the Kuntsevo District Department of the NKVD.[37] Kuntsevo was also near Moscow, and there Berg became a member of the NKVD “clan” headed by Alexander Radzivilovski, a high-ranking officer and deputy head of the NKVD in Moscow Province. These clans, pervasive in the NKVD, were formed on the patron-client model and served to protect their members amid the dangers of the Stalinist state. Radzivilovski, you may recall, began his career in the Crimea under Zemliachka and Kun in 1920. He was a Jew, as was his right-hand man, Grigory Yakubovich. Radzivilovski’s clan included many NKVD officers—Russian as well as Jewish—in Kuntsevo, which served as a recruiting ground for higher appointments in Moscow.[38]

Berg worked in Kuntsevo until mid-1936. Radzivilovski and his henchmen often came to Kuntsevo to relax in his nearby dacha. Berg was responsible for laying on the amenities, and the officers involved later admitted under interrogation to “immorality and degeneracy.”[39] Whatever this involved, Berg played a central role, and at his next posting, as head of the Vereya District NKVD, he was caught attempting to rape a prisoner (1937). He was sentenced to 20 days’ solitary confinement, then promoted.[40] He became the assistant secretary to the head of the Moscow NKVD, Stanislav Redens (who was married to the sister of Stalin’s wife). That summer Radzivilovski recommended Berg to head the Administrative and Economic Department of the Moscow Province NKVD, and Redens approved the appointment. “Berg, who had a long history of official reprimands, went instantly from being a minor figure—the assistant secretary to the head of the province’s NKVD—to a person with considerable authority.”[41] His rank was Lieutenant of State Security, equivalent to major in the army.

Berg assumed his new duties in August 1937, the exact moment that Stalin was launching a massive new purge, later called the Great Terror,[42] which lasted until November 1938 and totaled over 700,000 executions in about sixteen months. The Politburo—prompted by Stalin—had raised the alarm in early July about “anti-Soviet elements” causing sabotage and crime, and called for preemptive mass arrests and executions.[43] Each NKVD jurisdiction was directed to prepare quotas for arrests and executions.[44] These were collated and finalized by Ezhov, head of the NKVD, whose resulting formal order, “Operational Order No. 00447,” called for 270,000 arrests and 75,000 executions. “Eighteen months later these targets had been exceeded ninefold,”[45] as the purge acquired a horrifying momentum, the NKVD officers terrified to be seen as lacking in vigilance. Killing and burying people on this scale was a massive project,[46] and Redens assigned Berg the job for Moscow (the quota for which had been set at 5,000). He was responsible for finding suitable execution sites, moving the prisoners from the jail to the site, managing the executions, and burying the bodies. The now-famous Butovo shooting range, about fifteen miles due south of the Kremlin, became the biggest execution site/burial ground in the Moscow area, and Berg managed most of the massacre that took place there.[47]

NKVD Lieutenant Isai Berg

Upon the receipt of Operational Order No. 00447, the NKVD went into action. In each district of the vast country, officers began arresting people, based on long-accumulated files, or social standing, or other information. They then forced the prisoners to confess to

a fictitious crime. Officers obtained confessions using various tactics, most often through torture and beatings . . . during the [Great Terror] the NKVD undertook falsification [of confessions] on an industrial scale. Agents had to create a huge number of documents each day …[48]

One officer stated, “During the day we . . . made up fabricated interrogations for the accused and at night we made them sign under compulsion.”[49] Some people were forced to sign blank sheets of paper. Agents then sent these signed confessions up the chain of command, where they landed on the desk of the “troika,” a special body erected for the purpose. The troika in each province consisted of the head of the NKVD, the prosecutor, and the local Communist Party secretary. (Because Moscow was the capital, it had three troikas, plus several other sentencing bodies, all extra-judicial.) The troikas would process hundreds of cases at a time, passing sentence (death or gulag) on each person with little deliberation. Almost all of them involved Article 58, counterrevolutionary activity. Radzivilovski’s ally Grigory Yakubovich chaired the second Moscow troika, and Berg later stated, “Semyonov competed with [Y]akubovich to see who was the faster.. . . Semenov always went over to [Y]akubovich’s room and boasted that he had dispatched fifty cases more than him . . . and they were both delighted to have been able to pass sentence so quickly without even having glanced at the dossiers.”[50]

Two other Jews sat for a time on one of the various Moscow troikas, and also condemned hundreds or thousands to death: Vasili Karutsky and Vladimir Tsesarsky.[51]

Grigory Yakubovich

Vasili Karutsky

The NKVD photographed the unfortunate people fated to die at Butovo from the front and side (as in Vikhman’s photo above), and had their names entered on a list; Berg had a copy of the list and the photos. Around midnight, prison vans or trucks holding up to fifty people each were dispatched from the Moscow prisons to Butovo. The area, wooded and secluded, had searchlights and a long wooden building. A deep, long ditch had been prepared beforehand with earth-moving equipment. NKVD personnel or militia herded the people into the building, where each person’s identification was carefully checked, a lengthy process. Then the prisoners were led out of the building one at a time towards the trench, where an executioner would shoot them in the back of the head and cast them into the pit. The executioners, a special small team of Russians, were given as much vodka as they wanted. After a final round of paperwork, the job was done and the killers were driven back to Moscow.[52] The next day the bodies were covered with a layer of earth and the operation was repeated. From August 1937 through July 1938,[53] there were an average of 1645 executions a month or about 55 a day, but a few nights the number exceeded 400, and once reached 562.[54] Berg’s role in the actual killing is unclear; one historian states he “took part in the executions,” which does not necessarily mean he shot people.[55] Given the fact that he was responsible for the operation (and worked practically under the nose of Stalin), he probably would have been on site, ensuring the operation proceeded smoothly and finalizing paperwork. It is at least possible he participated in the shooting, for there was a lot of shooting to be done—almost 21,000 people were executed at Butovo between August 1937 and October 1938.[56]

Vladimir Tsesarsky

Whether or not Berg personally shot people at Butovo, he was interested in making the process as efficient as possible. He oversaw the introduction of a van designed to gas its inmates on the way to Butovo.[57] Berg felt pressure to accelerate the rate of executions to keep up with the avalanche of names coming down from the troikas. He also desired to relieve the strain on the executioners, who may have been called upon to shoot forty or fifty people a night, and reduce the possibility of resistance among the prisoners. Sources do not indicate whether Berg himself originated the idea, nor how many of the vans were utilized. (The vans were described as trucks disguised as bread-delivery vans.) In the Soviet Union at the time there was a general mania for technology, which probably gave some impetus to the desire to find a cleaner and more efficient method of killing than drunken killers and revolvers.

One version has NKVD personnel taking the condemned from the prisons, stripping them naked, binding and gagging them, and throwing them into the van before driving off.[58] On reaching Butovo, some of them might still be alive, albeit not much, and had to be finished off, or thrown alive into the pit. Later investigation showed that some of the dead had been buried while still alive; perhaps these were from the gas van.[59] We know that there was at least one group of people buried there who had no gunshot wounds:

[W]e know from limited archaeological excavations at Butovo in 1997 that there was at least one van load of victims since 55 . . . bodies found . . . don’t have the standard bullet wound to the back of the head/neck that is the hallmark of NKVD executions of this period and thus are almost certainly victims of Berg’s gas van(s).[60]

One author speculates that Berg may have operated multiple gas vans, over the space of months, with as many as five or even ten thousand victims.[61] Logistical problems, however, lead me to believe their use was quite limited. First, if the secret police bound people and threw them into the van, fifty people would not fit inside without great pains being taken to stack them. This would reduce the numbers and efficiency. The best method would be to jam people in, standing upright. Next, arriving at the site, they would have to laboriously unload the dead and dying by hand and throw them into the ditch, a very difficult task, much harder than having victims walk to the ditch under their own power. If they unloaded the bodies in this way, they could make prisoners do it, but the sources do not mention it, and the task would have to be overseen by NKVD personnel.[62]

The most likely and optimal scenario would be to jam the maximum number of people into the van, drive roughly 40 minutes to the site, back up to the ditch, and have prisoners unload them. Gathering, identifying, and loading the prisoners at Butyrka or Lubianka prisons, driving to Butovo, unloading, and driving back would take at least two and a half hours. Realistically, this means that only two trips could be done in a night. If, say, three trucks were in use, they could dispatch 300 victims a night, but with mechanical breakdowns and other problems, that number would often be lower. Meanwhile, in six hours or so 500 prisoners could be transported, examined, shot, and cast into a ditch, with no need of help from other prisoners. Gas vans were simply not as efficient as shooting, and the proof comes from the aftermath. There is no evidence that such gas vans were ever utilized again, not at Katyn or Vinnitsia, nor anywhere else the NKVD wanted to kill many people quickly. In addition, had Berg deployed fifteen or twenty trucks and killed many thousands with them, it would have represented a major phenomenon, with a very high likelihood of showing up clearly etched in the documentary record, which, as it is, has all the earmarks of recording something ephemeral: vague references, few details, few witnesses even remembering it. In the final analysis, the Berg gas van could have been nothing more than a short-lived novelty.

Nevertheless, Isai Berg the Jew stands guilty before all mankind of pioneering this infernal killing machine.

Berg would not oversee the final ten weeks of killing at Butovo, for he was arrested on August 4, 1938. The ostensible reason was drunkenness and indecent behavior, but the real reason was the breakup of his NKVD clan and the loss of its protection. Radzivilovski and Yakubovich had been transferred away from Moscow and the new superiors began to notice the pervasive corruption in the Kuntsevo district NKVD. The head of that district was arrested, and Berg was hauled in too because of his connections to Kuntsevo. Berg was interrogated—continuing with our theme—by a Jewish officer, Matvei Titelman, who demanding he confess merely to abuse of authority and not the dreaded “counterrevolutionary activity.”[63] After Beria took over the NKVD in November 1938, however, the attitude of the leadership hardened. (Stalin had called an end to the Terror and needed scapegoats to blame for the massacre getting so far out of hand.) Berg and many of his clan members were now accused of operating a counterrevolutionary conspiracy in the NKVD in the Moscow area, which was nonsense, like all the other accusations that year. Titelman was arrested in late November and his successor beat Berg with a truncheon to make him confess.[64] On March 7, 1939, Berg was sentenced to death by the Military Collegium of the Soviet Supreme Court and executed. Titelman had been shot a few days before; Yakubovich was shot in late February; Radzivilovski was shot in January 1940. The era of Jewish domination of the NKVD was crashing to an end, but the damage had been done.

Conclusion

The three persons described above, bloodthirsty as they were, had innumerable counterparts in the Bolshevik state. The number of Jews in the top-level leadership of the Soviet Union has been the subject of much debate, but far more important for ordinary Russians was the huge number of Jews in power all over the country, in mid-level positions, particularly in the secret police, with its power over life and death.[65] Few of these Jews had definitively cut their ties with the Jewish nation, although they attempted to hide that fact, and worked in and through the Russian nation and under the guise of international socialism.[66] Yet they could no more cast off their Jewish identity and motivation than a leopard can shed its spots. They were bent on revenge not only for the wrongs they believed they had sustained in Russia, but also because of the deeply-ingrained hatred for non-Jews they had developed and nourished since ancient times. Once they gained a foothold in power in Russia, no matter how lowly or tenuous, they began killing, and they continued killing for three decades or more, because it was rooted in their nature. When the Soviet state began crimping the power of the Jews and phasing out massacre as a tool of governance, the Jews suddenly lost their enthusiasm for Communism, Russian style.

In the end, there were few Jewish Communists, only Jews.

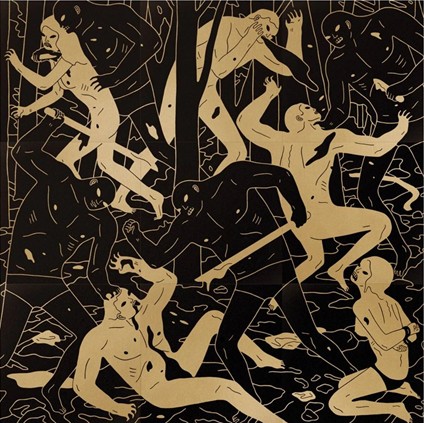

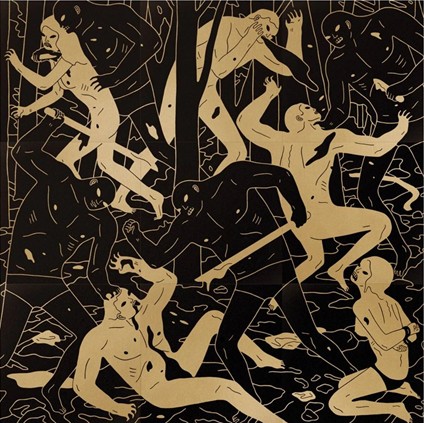

The Soviet Union and Jewish Bolshevism have passed away, but the Jewish nation—loaded with its grim memories and expectations—is stronger than ever. It has moved on to new venues and tactics, but the deep hatred still burns. We can see it in action almost everywhere in the modern world, at a time when the West is poised on the brink of dissolution. What will the next quarter century look like? If the Jews gain the power they dream of, it will look like this—

Rothschild-commissioned painting by Cleon Peterson

Rothschild-commissioned painting by Cleon Peterson

Fortunately, the West is awakening rapidly, largely because of the Jews themselves, who, with typical insolence, have exhibited their inner essence for the whole world to see. Their arrogance is stunning, their malice breathtaking, their power brazen. Events are clearly coming to a head. If God permits justice to triumph, the Jews will sustain a conclusive defeat in the coming war. The alternative is too terrible to contemplate. “If . . . the Jew conquers the nations of this world, his crown will become the funeral wreath of humanity . . .”[67]

[1] Sappers are combat engineers, building roads, bridges and fortifications, laying and clearing minefields, handling demolitions, etc.

[2] The sources on Vikhman are scant and can be contradictory. I’ve relied on the following:

a) Alexandra Polyak, Михаил Вихман — палач Одесской ЧК и жертва коммунистического режима (Mikhail Vikhman, Executioner of the Odessa Cheka and Victim of the Communist Regime) Jan 2020. https://zaodessu.com.ua/articles/mihail-vihman-palach-odesskoj-chk-i-zhertva-kommunisticheskogo-rezhima/

b) D. Sokolov, Чекист Вихман в необычной для себя роли (Chekist Vikhman in an Unusual Role) https://d-v-sokolov.livejournal.com/2189489.html?es=1

c) Tumshis M. and V. Zolotaryov. ЕВРЕИ В НКВД СССР 1936-1938 (Jews in the NKVD of the USSR, 1936-1938). 2nd edition, revised and expanded. Moscow: Dmitry Pozharsky University, 2017. Pages 192-94.

d) Abramov, Vadim. Евреи в КГБ (Jews in the KGB). Moscow: Izdatel Bystrov, 2006. Pages 142-43.

Abramov, Tumshis, and Polyak identify Vikhman as a Jew.

[3] The Red Terror in Russia (Westport CT: Hyperion Press, 1976), 203. Melgunov was a Russian writer and politician who opposed Bolshevik rule, was imprisoned and sentenced to death, then reprieved, whereupon he went abroad. He gathered information from Russian exiles (often witnesses to these events) in the voluminous Russian expatriate press in Western Europe and published it in 1924.

[4] George Leggett, The Cheka: Lenin’s Political Police (New York, 1981), 200, 198.

[5] This information appears in Polyak.

[6] Melgunov, Red Terror in Russia, 213.

[7] Two characteristics of early Communist rule in Russia were the rapid ascension of mediocre Jews to positions of power, and the constant shifting of personnel to different jobs and regions.

[8] Tumshis and Zolotaryov, Jews in the NKVD, 193.

[9] The sources give no details that might illustrate the story behind these events.

[10] Lynne Viola, Stalinist Perpetrators on Trial (New York: 2017), 27.

[11] Shimon Briman, “Stalin’s terror: Jewish victims and executioners,” at Forum Daily, https://www.forumdaily.com/en/politicheskie-repressii-evrei-zhertvy-i-palachi/

[12] Sokolov, “Chekist Vikhman in an Unusual Role.”

[13] It is amazing the permutations that the Jewish messianic ideal can go through when its one true object is overlooked.

[14] Sokolov.

[15] Cleared according to Soviet ideas of justice, of course. I doubt many of his own victims were rehabilitated.

[16] Kaganovich lived out his life alone in a sixth-floor apartment in the Frunze Embankment in Moscow. Like Molotov, his pension was a meager 120 rubles a month. His flat was described as “poor,” and he had no car or dacha. Certainly, Vikhman fared no better than that. From E. A. Rees, Iron Lazar: A Political Biography of Lazar Kaganovich (Anthem Press, 2013), 268.

[17] I found no hint of a wife or children for Vikhman.

[18] The sources I was able to access on Plastinina-Maizel were even scantier than those for Vikhman.

[19] Vladimir later worked for the NKVD, served in World War Two, and became an academic at Voronezh State University. He died in 1973. From Andrei Zhukov at Memorial: https://nkvd.memo.ru/index.php/Пластинин,_Владимир_Никандрович

[20] Natalia Golysheva, “Red Terror in the North “Did the civil war never end?” Dec 2017

https://www.bbc.com/russian/resources/idt-sh/red_terror_russian

[21] Orlando Figes, A People’s Tragedy: The Russian Revolution 1891-1924 (New York: Penguin Books, 1998), 647.

[22] Melgunov, 200.

[23] Rokiskis Rabinovičius, “Revekka Kedrova-Plastinina-Maizel” at his blog: http://rokiskis.popo.lt/2011/06/06/revekka-kedrova-plastinina-maizel/

[24] Leggett, The Cheka, 270.

[25] Leggett, 270.

[26] Alexander Solzhenitsyn, Zwei Hundert Jahren zusammen: Der Juden in der Sowjetunion (München, 2003), 141.

[27] Natalia Golysheva, “Red Terror in the North.”

[28] Leggett, The Cheka, 431 note 13.

[29] Melgunov, 199.

[30] Melgunov, 200.

[31] D. Sokolov, Михаил Кедров и Ревекка Пластинина (“Mikhail Kedrov and Rebeka Plastinina”) Sept 8, 2009 https://d-v-sokolov.livejournal.com/9061.html

[32] Donald Rayfield, Stalin and His Hangmen: The Tyrant and Those Who Killed for Him (New York: Random House, 2004), 84.

[33] Rayfield, 358.

[34] Solzhenitsyn, 141.

[35] It is also the site of Solzhenitsyn’s grave.

[36] Berg is a name common among Germans as well as Jews; Tumshis and Zhukov identify him as Jewish. Another note: two of our three subjects were born outside the Pale of Settlement, the vast area in which the Jews lamented they were “imprisoned.” Many Jews in Imperial Russia had the privilege of living outside it, and many more did so illegally.

[37] Tumshis and Zolotaryov, Jews in the NKVD, 125. The NKVD was the People’s Commissariat for Internal Affairs, equivalent to an Interior Ministry. It was established in July 1934 and absorbed the OGPU (the “Joint State Political Directorate”), the former Cheka, which became the GUGB (the “Main Directorate for State Security”). A Jew, Yakov Agranov, headed the GUGB, and another Jew, Genrikh Yagoda, headed the NKVD. Technically the OGPU/GUGB and the NKVD were separate but the terms are often used interchangeably.

[38] Alexander Vatlin, Agents of Terror: Ordinary Men and Extraordinary Violence in Stalin’s

Secret Police. (Edited & translated by Seth Bernstein. University of Wisconsin Press, 2016), 12-13.

[39] Vatlin, Agents of Terror, 14.

[40] Tumshis and Zolotaryov, 125.

[41] Vatlin, 15.

[42] By Robert Conquest, in his magisterial work, The Great Terror. This phase of Stalinist rule, 1937-38, came after an exhaustive succession of Communist massacres and upheavals: the Red Terror under Lenin, the destruction of the Church and murder of the clergy, forced collectivization of the farmers, breakneck industrialization with its dislocations, the vast expansion of the gulag and press-ganging its inmates into vast economic projects, and the Holodomor, to name just the highest peaks in the mountain range of Soviet atrocities.

[43] For a discussion of Stalin’s motives for the purge, see Vatlin, xi-xii and xxvi. Stalin wanted to eliminate a potential fifth column in case of war, which was considered imminent, clear out the old Bolshevik bureaucracy in favor of young Stalinist cadres, and cow the populace afresh to instill obedience.

[44] Seth Bernstein, Introduction, in Vatlin, Agents of Terror, xxiii. For the table of quotas for each region, see Karl Schlögel, Moscow 1937 (Polity Press, 2013), 495-96. It should not escape notice that a quota system for executions is the height of barbarity.

[45] Rayfield, 308.

[46] Unlike certain other genocides, a high percentage of the remains of the victims of the Great Terror have been found and identified. For information on burial sites, see “Map of Memory” at https://en.mapofmemory.org/

[47] There were several other major execution/burial grounds in the Moscow area: Donskoye Cemetery had a crematorium and thousands of executed prisoners were cremated there and buried in mass graves. Kommunarka was the site of over 6000 executions, mainly of high-ranking Bolsheviks.

[48] Vatlin, xiv.

[49] Vatlin, 31.

[50] Karl Schlögel, Moscow 1937, 482.

[51] Nérard François-Xavier, “The Butovo Shooting Range,” https://www.sciencespo.fr/mass-violence-war-massacre-resistance/fr/document/butovo-shooting-range

[52] Schlögel, 482-84.

[53] After early August, Berg was no longer involved.

[54] Schlögel, 472, 474.

[55] Schlögel, 482.

[56] 973 people were shot for being Christian Orthodox believers, including hundreds of priests, bishops, and abbots. Forty-nine priests were shot on one day, 10 December 1937. For comparison, two rabbis were killed. Schlögel, 487.

[57] At least five historians have stated that Berg used gas vans: Yevgenia Albats in The State Within a State: The KGB and its Hold on Russia—Past, Present, and Future (1994), Timothy Colton in Moscow: Governing the Socialist Metropolis (1998), Catherine Merridale in Night of Stone: Death and Memory in Twentieth Century Russia (2002), Alexander Solzhenitsyn in 200 Years Together (2002), and Robert Gellately in Lenin, Stalin, and Hitler: The Age of Social Catastrophe (2007). Merridale gives Colton as her source, but Colton quotes no source. Albats, Gellately, and Solzhenitsyn cite a 1990 Russian article by Evgeni Zhirnov, who read the original investigative record of Berg (when he was arrested by the NKVD) and provided details. A relevant portion of that article appears here, in a later article by Zhirnov: https://www.kommersant.ru/doc/1265324

In addition, at least six high-ranking Soviet secret police officers, from Berg’s time up to the 1990s, testified to the existence of Berg’s gas van. Karl Radl reviews the statements of five of them in “Stalin’s Willing Executioners: The Jewish Origin of Stalin’s Gas Vans,” https://karlradl14.substack.com/p/stalins-willing-executioners-the?utm_source=publication-search

[58] Tumshis and Zolotaryov, 126, citing the testimony of E. Zhirnov, who details the investigative record of Berg and testimony from contemporary NKVD men.

[59] Schlögel, 476.

[60] Karl Radl, “Stalin’s Willing Executioners.”

[61] Radl.

[62] A far-fetched idea: hydraulic dump-truck style vans, which could back up and dump the dead into the ditch automatically. There is no hint of such a truck in the sources, which all mention a vehicle disguised as a bread van. A dump truck would pose much greater technical problems to build than the described gas vans, and dump trucks were not widespread in Russia in 1937.

[63] Vatlin, 157-58, note 156.

[64] Vatlin, 67 and 157-58, note 156.

[65] For three decades I have collected data on Jewish Communists, and can testify that the number of Jews who held positions in the middle ranks of the Soviet State is immense. These were the people who governed the country on a day-to-day basis. The number of Jews in academia was equally large.

[66] Kevin MacDonald discusses this point cogently in the third chapter of The Culture of Critique.

[67] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (Reynal and Hitchcock, 1941), 84.

Given the suffocating interventionist hysteria of the time, major publishers declined to publish these volumes despite how many of them had been written by prominent, well-respected historians. Either the publishers were ardent interventionists themselves, or they feared backlash from anti-revisionists who wielded great power in America, just as they do today. Except for the Neilson volumes, which were self-published, these works found only two small publishing houses brave enough to publish them: Regnery and Devin-Adair.

Given the suffocating interventionist hysteria of the time, major publishers declined to publish these volumes despite how many of them had been written by prominent, well-respected historians. Either the publishers were ardent interventionists themselves, or they feared backlash from anti-revisionists who wielded great power in America, just as they do today. Except for the Neilson volumes, which were self-published, these works found only two small publishing houses brave enough to publish them: Regnery and Devin-Adair.

Vikhman in the hands of Jewish interrogators

Vikhman in the hands of Jewish interrogators Nikandr Plastinina, Vladimir, and Revekka in Geneva 1916

Nikandr Plastinina, Vladimir, and Revekka in Geneva 1916 Revekka, Mikhail Kedrov and his son Igor

Revekka, Mikhail Kedrov and his son Igor Archangelsk Oblast (Province)

Archangelsk Oblast (Province)

Rothschild-commissioned painting by Cleon Peterson

Rothschild-commissioned painting by Cleon Peterson