Two Ingroup Morality Items

As noted ad nauseum at TOO, while Diaspora Jews in the West continue to promote immigration and multiculturalism as intrinsic goods and unquestioned moral ideals, in Israel the whole point of public policy is to retain its Jewish character. The most recent example is shipping to Sweden dozens of African refugees living in Israel. Patrick Cleburne’s account at VDARE says it all:

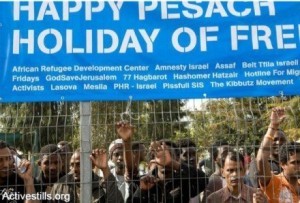

As noted ad nauseum at TOO, while Diaspora Jews in the West continue to promote immigration and multiculturalism as intrinsic goods and unquestioned moral ideals, in Israel the whole point of public policy is to retain its Jewish character. The most recent example is shipping to Sweden dozens of African refugees living in Israel. Patrick Cleburne’s account at VDARE says it all:

- The similar size and ethnic diversity of the two countries means that the only rationale for sending Africans to Sweden is that Sweden cares nothing about retaining a Swedish identity, whereas Israel cares deeply about remaining a Jewish state;

- While the U.S. government policy on immigration and multiculturalism remains at odds with the interests of the traditional people of the West, especially the working class (so, as Cleburne notes, we can expect many of these African refugees to end up in the U.S.), the Israeli government sticks up for their own people: Interior Minister Gideon Sa’ar said he was “not very impressed with all the crying and complaining” by business owners whose employees were on strike. “With all due respect to the restaurant and café owners in crisis, or those whose cleaning staff didn’t show up, this will not determine Israel’s national policy. On the contrary, let’s think about those Israelis who have lost their jobs [to migrant workers].”

Given that immigration and multiculturalism are presented as moral imperatives in the West, this results in a double moral standard—one morality for the ingroup and a quite different morality toward the outgroup; the theme of Jewish moral particularism. Unlike the addiction of the West to moral universalism, Jewish groups behave as a foreign policy realist (or evolutionary psychologist) expects states to behave. They simply pursue their interests with the aim of surviving and prospering.

And that means pursuing radically different strategies depending on whether Jews are a demographic majority or a tiny minority. In the West, the organized Jewish community avidly pursues displacement-level immigration and multiculturalism as tools to render the traditional majorities relatively powerless and incapable of mounting attacks on Jews. In Israel, the goal is to retain Jewish identity and minimize the presence and the influence of non-Jews—goals that are enthusiastically supported by Diaspora Jews and Jewish organizations.