The Extreme Hyper-Ethnocentrism of Jews on Display in Israeli attitudes toward the Gaza War

If you know anything about traditional Jewish ethics (i.e., Jewish ethics before a great deal of intellectual work was performed aimed at providing a rationale for Judaism as a modern religion in the West—apparent in the Wikipedia article on Jewish ethics), you know that pre-Enlightenment Jewish ethics was entirely based on whether actions applied to the ingroup or the outgroup. Non-Jews had no moral worth and could be exploited or even murdered as long as doing so did not threaten the interests of the wider Jewish community. I have written a great deal on Jewish ingroup morality, beginning with the Chapter 6 in A People That Shall Dwell Alone:

Business and social ethics as codified in the Bible and the Talmud took strong cognizance of group membership in a manner that minimized oppression within the Jewish community, but not between Jews and gentiles. Perhaps the classic case of differential business practices toward Jews and gentiles, enshrined in Deuteronomy 23, is that interest on loans could be charged to gentiles, but not to Jews. Although various subterfuges were sometimes found to get around this requirement, loans to Jews in medieval Spain were typically made without interest (Neuman 1969, I:194), while those to Christians and Moslems were made at rates ranging from 20 to 40 percent (Lea 1906-07, I:97). Hartung (1992) also notes that Jewish religious ideology deriving from the Pentateuch and the Talmud took strong cognizance of group membership in assessing the morality of actions ranging from killing to adultery. For example, rape was severely punished only if there were negative consequences to an Israelite male. While rape of an engaged Israelite virgin was punishable by death, there was no punishment at all for the rape of a non-Jewish woman. In Chapter 4, it was also noted that penalties for sexual crimes against proselytes were less than against other Jews.

Hartung notes that according to the Talmud (b. Sanhedrin 79a) an Israelite is not guilty if he kills an Israelite when intending to kill a heathen. However, if the reverse should occur, the perpetrator is liable to the death penalty. The Talmud also contains a variety of rules enjoining honesty in dealing with other Jews, but condoning misappropriation of gentile goods, taking advantage of a gentile’s errors in business transactions, and not returning lost articles to gentiles (Katz 1961a, 38).[ii]

Katz (1961a) notes that these practices were modified in the medieval and post‑medieval periods among the Ashkenazim in order to prevent hillul hashem (disgracing the Jewish religion). In the words of a Frankfort synod of 1603, “Those who deceive Gentiles profane the name of the Lord among the Gentiles” (quoted in Finkelstein 1924, 280). Taking advantage of gentiles was permissible in cases where hillul hashem did not occur, as indicated by rabbinic responsa that adjudicated between two Jews who were contesting the right to such proceeds. Clearly this is a group-based sense of ethics in which only damage to one’s own group is viewed as preventing individuals from profiting at the expense of an outgroup. “[E]thical norms applied only to one’s own kind” (Katz 1961a, 42).

Evolutionary psychologist/anthropologist John Hartung, referenced above, has continued his work on Jewish ethics on his website strugglesforexistence.com; note particularly “Thou Shalt Not Kill … Whom?.” The Jewish double ethical standard has been a major theme of anti-Semitism throughout the ages, discussed in Chapter 2 of Separation and Its Discontents; these intellectuals are good examples:

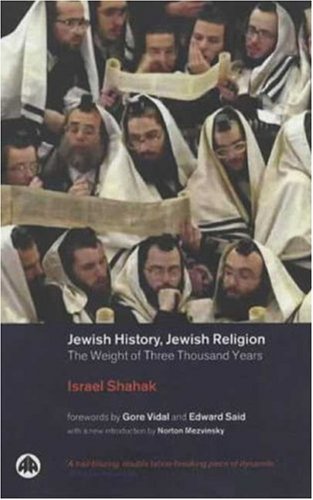

Beginning with the debates between Jews and Christians during the Middle Ages (see Chapter 7) and reviving in the early 19th century, the Talmud and other Jewish religious writings have been condemned as advocating a double standard of morality, in addition to being anti-Christian, nationalistic, and ethnocentric, a view for which there is considerable support (see Hartung 1995; Shahak 1994; PTSDA, Ch. 6). For example, the [Cornell University] historian Goldwin Smith (1894, 268) provides a number of Talmudic passages illustrating the “tribal morality” and “tribal pride and contempt of common humanity” (p. 270) he believed to be characteristic of Jewish religious writing. Smith provides the following passage suggesting that subterfuges may be used against gentiles in lawsuits unless such behavior would cause harm to the reputation of the entire Jewish ingroup (i.e., the “sanctification of the Name”):

When a suit arises between an Israelite and a heathen, if you can justify the former according to the laws of Israel, justify him and say: ‘This is our law’; so also if you can justify him by the laws of the heathens justify him and say [to the other party:] ‘This is your law’; but if this can not be done, we use subterfuges to circumvent him. This is the view of R. Ishmael, but R. Akiba said that we should not attempt to circumvent him on account of the sanctification of the Name. Now according to R. Akiba the whole reason [appears to be,] because of the sanctification of the Name, but were there no infringement of the sanctification of the Name, we could circumvent him! (Baba Kamma fol. 113a)

Smith comments that “critics of Judaism are accused of bigotry of race, as well as bigotry of religion. The accusation comes strangely from those who style themselves the Chosen People, make race a religion, and treat all races except their own as Gentiles and unclean” (p. 270).

[Economist, historian, sociologist] Werner Sombart (1913, 244–245) summarized the ingroup/outgroup character of Jewish law by noting that “duties toward [the stranger] were never as binding as towards your ‘neighbor,’ your fellow-Jew. Only ignorance or a desire to distort facts will assert the contrary. . . . [T]here was no change in the fundamental idea that you owed less consideration to the stranger than to one of your own people. . . . With Jews [a Jew] will scrupulously see to it that he has just weights and a just measure; but as for his dealings with non-Jews, his conscience will be at ease even though he may obtain an unfair advantage.” To support his point, Sombart provides the following quote from Heinrich Graetz, a prominent 19th-century Jewish historian:

To twist a phrase out of its meaning, to use all the tricks of the clever advocate, to play upon words, and to condemn what they did not know . . . such were the characteristics of the Polish Jew. . . . Honesty and right-thinking he lost as completely as simplicity and truthfulness. He made himself master of all the gymnastics of the Schools and applied them to obtain advantage over any one less cunning than himself. He took a delight in cheating and overreaching, which gave him a sort of joy of victory. But his own people he could not treat in this way: they were as knowing as he. It was the non-Jew who, to his loss, felt the consequences of the Talmudically trained mind of the Polish Jew. (In Sombart 1913, 246)

… Pioneering German sociologist Max Weber (1922, 250) also verified this perception, noting that “As a pariah people, [Jews] retained the double standard of morals which is characteristic of primordial economic practice in all communities: What is prohibited in relation to one’s brothers is permitted in relation to strangers.”

A common theme of late-18th- and 19th-century German anti-Semitic writings emphasized the need for moral rehabilitation of the Jews—their corruption, deceitfulness, and their tendency to exploit others (Rose 1990). Such views also occurred in the writings of Ludwig Börne and Heinrich Heine (both of Jewish background) and among gentile intellectuals such as Christian Wilhelm von Dohm (1751–1820) and Karl Ferdinand Glutzkow (1811–1878), who argued that Jewish immorality was partly the result of gentile oppression. Theodor Herzl viewed anti-Semitism as “an understandable reaction to Jewish defects” brought about ultimately by gentile persecution: Jews had been educated to be “leeches” who possessed “frightful financial power”; they were “a money-worshipping people incapable of understanding that a man can act out of other motives than money” (in Kornberg 1993, 161, 162). Their power drive and resentment at their persecutors could only find expression by outsmarting Gentiles in commercial dealings” (Kornberg 1993, 126). Theodor Gomperz, a contemporary of Herzl and professor of philology at the University of Vienna, stated “Greed for gain became . . . a national defect [among Jews], just as, it seems, vanity (the natural consequence of an atomistic existence shunted away from a concern with national and public interests)” (in Kornberg 1993, 161).

So we should not be surprised to find that a great many Jews view Palestinians as having no moral worth. They are seen as literally not human, as noted by the prominent Lubavitcher Rebbe Schneerson:

We do not have a case of profound change in which a person is merely on a superior level. Rather we have a case of…a totally different species…. The body of a Jewish person is of a totally different quality from the body of [members] of all nations of the world…. The difference of the inner quality [of the body]…is so great that the bodies would be considered as completely different species. This is the reason why the Talmud states that there is an halachic difference in attitude about the bodies of non-Jews [as opposed to the bodies of Jews]: “their bodies are in vain”…. An even greater difference exists in regard to the soul. Two contrary types of soul exist, a non-Jewish soul comes from three satanic spheres, while the Jewish soul stems from holiness. (see here)

Different species have no moral obligations to each other—predator and prey, parasite and host, humans domesticating cattle and eating meat and dairy products.

This ethic differs radically from Western universalism as epitomized by Kant’s moral imperative: “Act only according to that maxim whereby you can at the same time will that it should become a universal law.” Moral universalism is fundamental to Western individualism: Groups per se have no moral status—the exact opposite of Judaism.

Jews may often present themselves as the height of morality, but appearances can be deceiving. From my review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century:

In 1923, several Jewish intellectuals published a collection of essays admitting the “bitter sin” of Jewish complicity in the crimes of the Revolution. In the words of a contributor, I. L. Bikerman, “it goes without saying that not all Jews are Bolsheviks and not all Bolsheviks are Jews, but what is equally obvious is that disproportionate and immeasurably fervent Jewish participation in the torment of half-dead Russia by the Bolsheviks” (p. 183). Many of the commentators on Jewish Bolsheviks noted the “transformation” of Jews: In the words of another Jewish commentator, G. A. Landau, “cruelty, sadism, and violence had seemed

alien to a nation so far removed from physical activity.” And another Jewish commentator, Ia. A Bromberg, noted that: the formerly oppressed lover of liberty had turned into a tyrant of “unheard-of-despotic arbitrariness”…. The convinced and unconditional opponent of the death penalty not just for political crimes but for the most heinous offenses, who could not, as it were, watch a chicken being killed, has been transformed outwardly into a leather-clad person with a revolver and, in fact, lost all human likeness (pp. 183–184). This psychological “transformation” of Russian Jews was probably not all that surprising to the Russians themselves, given Gorky’s finding that Russians prior to the Revolution saw Jews as possessed of “cruel egoism” and that they were concerned about becoming slaves of the Jews.

At least until the Gaza war, Jews have successfully depicted themselves as moral paragons and as champions of the downtrodden in the contemporary West. The organized Jewish community pioneered the civil rights movement and have been staunch champions of liberal immigration and refugee policies, always with the rhetoric of moral superiority (masking obviously self-interested motivations of recruiting non-Whites who could be relied on to ally with Jews in their effort to lessen the power of the erstwhile White majority by making them subjects of a multicultural, anti-White political hegemony; here, p. 26ff).

This weighs heavily on my mind. This Jewish pose of moral superiority is a dangerous delusion, and we must be realistic what the future holds as Whites continue to lose political power in all Western countries. When the gloves come off, there is no limit to what Jews in power may do if their present power throughout the West continues to increase. The ubiquitous multicultural propaganda of ethnic groups living in harmony throughout the West will quickly be transformed into a war of revenge for putative historical grievances that Jews harbor against the West, from the destruction of the Second Temple by the Romans to the events of World War II. This same revenge was fatal to many millions of Russians and Ukrainians. It’s the fate of the Palestinians that we are seeing unfold before our eyes. Two recent articles brought this home vividly.

Megan Stack in The New York Times:

Israel has hardened, and the signs of it are in plain view. Dehumanizing language and promises of annihilation from military and political leaders. Polls that found wide support for the policies that have wreaked devastation and starvation in Gaza. Selfies of Israeli soldiers preening proudly in bomb-crushed Palestinian neighborhoods. A crackdown on even mild forms of dissent among Israelis.

The Israeli left — the factions that criticize the occupation of Palestinian lands and favor negotiations and peace instead — is now a withered stump of a once-vigorous movement. In recent years, the attitudes of many Israelis toward the “Palestinian problem” have ranged largely from detached fatigue to the hard-line belief that driving Palestinians off their land and into submission is God’s work. …

But Israel’s slaughter in Gaza, the creeping famine, the wholesale destruction of neighborhoods — this, polling suggests, is the war the Israeli public wanted. A January survey found that 94 percent of Jewish Israelis said the force being used against Gaza was appropriate or even insufficient. In February, a poll found that most Jewish Israelis opposed food and medicine getting into Gaza. It was not Mr. Netanyahu alone but also his war cabinet members (including Benny Gantz, often invoked as the moderate alternative to Mr. Netanyahu) who unanimously rejected a Hamas deal to free Israeli hostages and, instead, began an assault on the city of Rafah, overflowing with displaced civilians.

“It’s so much easier to put everything on Netanyahu, because then you feel so good about yourself and Netanyahu is the darkness,” said Gideon Levy, an Israeli journalist who has documented Israel’s military occupation for decades. “But the darkness is everywhere.” …

Like most political evolutions, the toughening of Israel is partly explained by generational change — Israeli children whose earliest memories are woven through with suicide bombings have now matured into adulthood. The rightward creep could be long-lasting because of demographics, with modern Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox Jews (who disproportionately vote with the right) consistently having more babies than their secular compatriots.

Most crucially, many Israelis emerged from the second intifada with a jaundiced view of negotiations and, more broadly, Palestinians, who were derided as unable to make peace. This logic conveniently erased Israel’s own role in sabotaging the peace process through land seizures and settlement expansion. But something broader had taken hold — a quality that Israelis described to me as a numb, disassociated denial around the entire topic of Palestinians.“The issues of settlements or relations with Palestinians were off the table for years,” Tamar Hermann told me. “The status quo was OK for Israelis.”

Ms. Hermann, a senior research fellow at the Israel Democracy Institute, is one of the country’s most respected experts on Israeli public opinion. In recent years, she said, Palestinians hardly caught the attention of Israeli Jews. She and her colleagues periodically made lists of issues and asked respondents to rank them in order of importance. It didn’t matter how many choices the pollsters presented, she said — resolving the Israeli-Palestinian conflict came in last in almost all measurements. …

or nearly two decades — starting with the quieting of the second intifada and ending calamitously on Oct. 7 — Israel was remarkably successful at insulating itself from the violence of the occupation. Rockets fired from Gaza periodically rained down on Israeli cities, but since 2011, Israel’s Iron Dome defense system has intercepted most of them. The mathematics of death heavily favored Israel: From 2008 until Oct. 7, more than 6,000 Palestinians were killed in what the United Nations calls “the context of occupation and conflict”; during that time, more than 300 Israelis were killed.

Human rights organizations — including Israeli groups — wrote elaborate reports explaining why Israel is an apartheid state. That was embarrassing for Israel, but nothing really came of it. The economy flourished. Once-hostile Arab states showed themselves willing to sign accords with Israel after just a little performative pestering about the Palestinians.

Those years gave Israelis a taste of what may be the Jewish state’s most elusive dream — a world in which there simply did not exist a Palestinian problem.

Daniel Levy, a former Israeli negotiator who is now president of the U.S./Middle East Project think tank, describes “the level of hubris and arrogance that built up over the years.” Those who warned of the immorality or strategic folly of occupying Palestinian territories “were dismissed,” he said, “like, ‘Just get over it.’”

If U.S. officials understand the state of Israeli politics, it doesn’t show. Biden administration officials keep talking about a Palestinian state. But the land earmarked for a state has been steadily covered in illegal Israeli settlements, and Israel itself has seldom stood so unabashedly opposed to Palestinian sovereignty.

There’s a reason Mr. Netanyahu keeps reminding everyone that he’s spent his career undermining Palestinian statehood: It’s a selling point. Mr. Gantz, who is more popular than Mr. Netanyahu and is often mentioned as a likely successor, is a centrist by Israeli standards — but he, too, has pushed back against international calls for a Palestinian state.

Daniel Levy describes the current divide among major Israeli politicians this way: Some believe in “managing the apartheid in a way that gives Palestinians more freedom — that’s [Yair] Lapid and maybe Gantz on some days,” while hard-liners like Mr. Smotrich and Security Minister Itamar Ben Gvir “are really about getting rid of the Palestinians. Eradication. Displacement.”

The carnage and cruelty suffered by Israelis on Oct. 7 should have driven home the futility of sealing themselves off from Palestinians while subjecting them to daily humiliations and violence. As long as Palestinians are trapped under violent military occupation, deprived of basic rights and told that they must accept their lot as inherently lower beings, Israelis will live under the threat of uprisings, reprisals and terrorism. There is no wall thick enough to suppress forever a people who have nothing to lose.

* * *

Ilana Mercer is a Jewish woman from South Africa who has posted on various conservative sites. Here she states the unmentionable about Israel—and by implication, a very wide swath of Jews living in the West: that sociopathy toward non-Jews is entirely mainstream among Jews. No one should be surprised by this. My only quibble is that real sociopaths have no guilt and even take pleasure in harming others without regard to their religion or ethnicity. But these same Jews who are reveling in slaughtering Palestinians are Jewish patriots and love their own people. But they have an extreme form of ingroup morality—a morality that is intimately linked to what I call Jewish “hyper-ethnocentrism” (e.g., here).

Ilana Mercer at Lew Rockwell.com: Sad To Say, but, by the Numbers, Israeli Society Is Systemically Sociopathic.

In teasing out right from wrong, discriminate we must between acts that are criminal only because The State has criminalized them (mala prohibita), as opposed to acts which are universally evil (malum in se). Israel’s sacking of Gaza is malum in se, universally evil. Gaza is clearly an easy case in ethics. It’s not as though the genocide underway in Gaza could ever be finessed or gussied up.

Yet in Israel, no atrocity perpetrated by the IDF (Israel Defense Forces) in Gaza is too conspicuous to ignore. One of the foremost authorities on Gaza, Dr. Norman Finkelstein, calls Israel a Lunatic State. “It is certainly not a Jewish State,” he avers. “A murderous nation, a demonic nation,” roars Scott Ritter—legendary, larger-than-life American military expert, to whose predictive, reliable reports from theaters of war I’ve been referring since 2002. That the Jewish State is genocidal is not in dispute. But, what of Israeli society? Is it sick, too? What of the Israeli anti-government protesters now flooding the streets of metropolitan Israel? How do they feel about the incessant, industrial-scale campaign of slaughter and starvation in Gaza, north, center and south?

They don’t.

In desperate search for a universal humanity—a transcendent moral sensibility—among the mass of Israelis protesting the State; I scoured many transcripts over seven months. I sat through volumes of video footage, searching as I was for mention, by Israeli protesters, of the war of extermination being waged in their name, on their Gazan neighbors. I found none. Much to my astonishment, I failed to come across a single Israeli protester who cried for anyone but himself, his kin and countrymen, and their hostages. Israelis appear oblivious to the unutterable, irreversible, irremediable ruin adjacent.

Again: I found no transcendent humanity among Israeli protesters; no allusion to the universal moral order to which international humanitarian law, the natural law and the Sixth Commandment give expression. I found only endless iterations among Jewish-Israelis of their sectarian interests.

For their part, protesters merely want regime change. They saddle Netanyahu solely with the responsibility for hostages entombed in Gaza, although, Benny Gantz (National Unity Party), ostensible rival to Bibi Netanyahu (Likud), and other War Cabinet members, are philosophically as one (Ganz had boasted, in 2014, that he would “send parts of Gaza back to the Stone Age”). With respect to the holocaustal war waged on Gaza, and spreading to the West Bank, there is no chasm between these and other squalid Jewish supremacists who make up “Israel’s wartime leadership.”

If you doubt my findings with respect to the Israeli protesters, note the May 11 droning address of protester Na’ama Weinberg, who demanded a change of government. Weinberg condemned the invasion of Rafah and a lack of a political strategy as perils to both hostage- and national survival. She lamented the “unspeakable torture” faced by the hostages. When Weinberg mentioned “evacuees neglected,” I lit up. Nine-hundred thousand Palestinians have been displaced from Rafah in the last two weeks. Forty percent of Gaza’s population. My hope was fleeting. It soon transpired that Weinberg meant citizens of Israeli border communities evacuated. That was the extent of Weinberg’s sympathies for the “slaughter house of civilians” down the road. Hers was nothing but a lower-order sectarian sensibility.

The grim spareness of Israeli protester sentiment has been widely noticed.

Writing for Foreign Policy, an American mainstream magazine, Mairav Zonszein, scholar with the International Crisis Group, observes the following:

‘The thousands of Israelis who are once again turning out to march in the streets are not protesting the war. Except for a tiny handful of Israelis, Jews, and Palestinians, they are not calling for a cease-fire or an end to the war—or for peace. They are not protesting Israel’s killing of unprecedented numbers of Palestinians in Gaza or its restrictions on humanitarian aid that have led to mass starvation. (Some right-wing Israelis even go further by actively blocking aid from entering the strip.) They are certainly not invoking the need to end military occupation, now in its 57th year. They are primarily protesting Netanyahu’s refusal to step down and what they see as his reluctance to seal a hostage deal.’

Public incitement continues apace. Genocidal statements saturate Israeli society. The “lovely” Itamar Ben Gvir has provided an update to his repertoire, the kind chronicled so well by the South Africans (this one included). On May 14, to the roar of the crowd, Israel’s national security minister urged anew that Palestinians be voluntarily encouraged to emigrate (as if anything that has befallen the Palestinians of Gaza, since October 7, has been “voluntary”). He was speaking at a settler rally on the northern border of Gaza, in which thousands of yahoos watched the “fireworks” on display over Gaza, and cheered for looting the land of the dead and dying there.

“It’s the media’s fault,” you’ll protest. “Israelis, like Americans, are merely brainwashed by their media.”

Inarguably, Israeli media—from Arutz 7, to Channel 12 (“[Gazans need] to die ‘hard and agonizing deaths’), to Israel Today, to Now 14 (“We will slaughter you and your supporters”), and the lowbrow, sub-intelligent vulgarians of i24—are a self-obsessed, energetic Idiocracy.

These media feature excitable sorts, volubly imparting their atavistic, primitive tribalism in ugly, anglicized, Pidgin Hebrew. And, each one of these specimen always has a “teoria”: a theory.

Naveh Dromi is a lot more appealing in visage and voice than i24’s anchor Benita Levin, a harsh and vinegary South African Kugel. Dromi is columnist for a Ha’aretz, the most highbrow of Israel’s (center-left) dailies. Ha’aretz once had intellectual ballast. In her impoverished Hebrew, Dromi has tweeted about her particular “teoria”: “a second Nakba” is a coming. Elsewhere she has rasped a-mile-a-minute about “the Palestinians as a redundant group.” Nothing crimsons her lovely cheeks.

Such statements of Jewish supremacy pervade Jewish-Israeli media. But, no; it’s not the Israeli media’s fault. The closing of the Israeli mind is entirely voluntary.

According to a paper from Oxford Scholarship Online, the “media landscape in Israel” evinces “healthy competition” and declining concentration. “[C]alculated on a per-capita basis,” “the number of media voices in Israel,” overall, “is near the top of the countries investigated.”

Israel has a robust, and privately owned media. These media cater to the Israeli public, which has a filial stake in lionizing the Israel Defense Forces (IDF), in which each and every son and daughter serve. For this reason, avers Ha’aretz’s Gideon Levi, in his many YouTube television interviews, the military is the country’s golden calf.

Mainstream public opinion, Levi insists, molds the media, not the obverse.

Levi attests that right-wing and left-wing media are as one when it comes to the subject of the IDF and the Palestinian People. And in this, Israeli media reflect mainstream public opinion. It is the public that wishes to see nothing of the suffering in Gaza, and takes care never to disparage or doubt the IDF. For their part, military journalists are no more than embeds, in bed with the military.

At least until now, Israelis have been largely indifferent to their army’s orgiastic, indiscriminate bloodletting in Gaza. Most were merely demanding a return of their hostages, and the continuance of the assault on Gazans, punctured by periodic cease fires.

So, is Jewish-Israeli society sick, too?

When “88 percent of Jewish-Israeli interviewees” give “a positive assessment of the performance of the IDF in Gaza until now” (Tamar Hermann, “War in Gaza Survey 9,” Israel Democracy Institute, January 24, 2024), and “[a]n absolute majority (88%) also justifies the scope of casualties on the Palestinian side”; (Gershon H. Gordon, The Peace Index, January 2024, Faculty of Social Sciences, Tel Aviv University)—it is fair to conclude that the diabolical IDF is, for the most, the voice of the Jewish-Israeli commonwealth.

Consider: By January’s end, the Gaza Strip had, by and large, already been rendered uninhabitable, a moonscape. Nevertheless, 51 percent of Jewish-Israelis said they believed the IDF was using an appropriate amount (51%) or not enough force (43%) in Gaza. (Source: Jerusalem Post staff, “Jewish Israelis believe IDF is using appropriate force in Gaza,” January 26, 2024.)

Note: Polled opinion was not split between Israelis for genocide and Israelis against it. Rather, the division in Israeli society appeared to be between Jewish-Israelis for current levels of genocide versus those for greater industry in what were already industrial-levels and methods of murder.

Attitudes in Israel have only hardened since: By mid-February, 58 percent of this Jewish cohort was grumbling that not enough force had been deployed to date; and 68 percent did “not support the transfer of humanitarian aid to Gaza.” (Jerusalem Post Staff, “Majority of Jewish Israelis opposed to demilitarized Palestinian state,” February 21, 2024.) [One wonders if the Biden admin’s humanitarian pier — the one that drifted into the sea shortly after it was installed — was sabotaged.]

Scrap the “hardened” verb. Attitudes in Jewish Israel have not merely hardened, but bear the hallmark of societal sociopathy.

When asked, in particular, “to what extent should Israel take into consideration the suffering of the Palestinian population when planning the continuation of the fighting there,” Jewish-Israelis sampled have remained consistent through the months of the onslaught on Gaza, from late in October of 2023 to late in March of 2024. The Israel Democracy Institute, a polling organization, found that,

‘[D]espite the progress of the war in Gaza and the harsh criticism of Israel from the international community regarding the harm inflicted on the Palestinian population, there remains a very large majority of the Jewish public who think that Israel should not take into account the suffering of Palestinian civilians in planning the continuation of the fighting. By contrast, a similar majority of the Arab public in Israel take the opposite view, and think this suffering should be given due consideration.’ (Tamar Hermann, Yaron Kaplan, Dr. Lior Yohanani, “War in Gaza Survey 13,” Israel Democracy Institute, March 26, 2024.)

Large majorities of the Israeli Center (71 percent) and on the Right (90 percent) say that “Israel should only take into account the suffering of the Palestinian population to a small extent or should not do so at all.”

Let us, nevertheless, end this canvas with the “good” news: On the “bleeding heart” Israeli Left; “only” (I’m being cynical) 47 percent of a sample “think that Israel should not take into consideration the suffering of Palestinian civilians in Gaza or should do so only to a small extent, while 50 percent think it should consider their plight to a fairly large or very large extent.” (Ibid.)

In other words, the general run of the Jewish-Israeli Left tends to think that the plight of Gazans should be considered, but not necessarily ended.

On the facts, and, as I have had to, sadly, show here, both the Israeli state and civil society are driven by Jewish supremacy, the kind that sees little to no value in Palestinian lives and aspirations. …

* * *

Again, any student of Jewish history, Jewish ethics, and Jewish hyper-ethnocentrism should not be surprised by this. The existential problem for us is that we have to avoid the fate of the Russians, the Ukrainians, and the Palestinians. Jews in power will do what they can to oppose the interests of non-Jews of whatever society they reside in, whether by promoting nation-destroying immigration and refugee policy or — when they have absolute power — torture, imprisonment, and genocide.

The contrast between the hyper-ethnocentric Israeli media described by Mercer and the anti-White, utopian, multicultural media in the West, much of it owned and staffed by Jews, couldn’t be greater. Whereas the Israeli media reflect the ethnocentrism of the Israeli public, the media in the West do their best to shape public attitudes, including constant and ever-increasing anti-White messaging — morally phrased messaging that is effective with very large percentages of White people, especially women, likely for evolutionary reasons peculiar to Western individualist cultures (here, Ch. 8). The state of the Western media is Exhibit A of Jews as a hostile elite in the West.

It should be obvious at this point that Western cultures are the opposite of Middle Eastern cultures where ethnocentrism and collectivism reign. Westerners have far less of the ingroup-outgroup thinking so typical of Jewish culture throughout history.

Individualism has served us poorly indeed and has been a disaster for Western peoples. Nothing short of a strong ingroup consciousness in which Jews are seen as a powerful and very dangerous outgroup will save us now.

“Britain’s anti-EU ‘Leave’ campaign has helped create a public discourse of prejudice and fear, couched in a parochial nationalism, that Jews in Britain must challenge.”

“Britain’s anti-EU ‘Leave’ campaign has helped create a public discourse of prejudice and fear, couched in a parochial nationalism, that Jews in Britain must challenge.”