Tristan Tzara and the Jewish Roots of Dada, Part 3

Dada in New York

According to Marcel Duchamp’s own account, in late 1916 or early 1917 he and Francis Picabia received a book sent by an unknown author, one Tristan Tzara. The book was called The First Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine and had just been published in Zurich. In this work Tzara declared Dada to be “irrevocably opposed to all accepted ideas promoted by the ‘zoo’ of art and literature, whose hallowed walls of tradition he wanted to adorn with multicolored shit.”[i] Duchamp later said: “We were intrigued but I didn’t know who Dada was, or even that the word existed.”[ii] Tzara’s scatological message was the catalyst for the establishment of the antipatriotic and anti-rationalist Dada message in New York, and it may well have informed Duchamp’s decision to submit his infamous Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

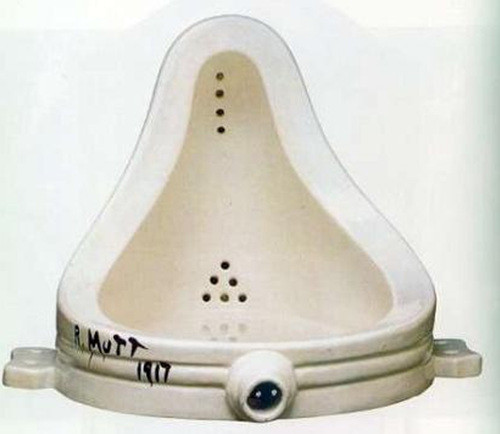

In February 1917 Duchamp famously sent the Independent an upside-down urinal entitled Fountain, signing it R. Mutt (famously photographed by Alfred Stieglitz). By doing so Duchamp directed attention away from the work of art as a material object, and instead presented it as something which was an idea. In doing so he shifted the emphasis from making to thinking.

Duchamp later did the same with a bottle rack and other items. Through subversive gestures like these he parodied the Futurist machine aesthetic by exhibiting untreated objets trouvés or readymade objects. To his great surprise these became accepted by the mainstream art world.

Alongside the Frenchman Marcel Duchamp (1887–1968) and the French-born Cuban Francis Picabia (1879–1953) were the American Jews Morton Schamberg (1881–1918) and Man Ray, (1890–1977). The work of the New York Dadaists was focused around the gallery of the Jewish photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his publication 291, and the collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg. Picabia later described this group as “a motley international band which turned night into day, conscientious objectors of all nationalities and walks of life living into an inconceivable orgy of sexuality, jazz and alcohol.”[iii] The group members hotly debated such topics as art, literature, sex, politics and psychoanalysis. Dada in New York stayed in contact with Dada in Zurich, with Stieglitz regularly corresponding with Tristan Tzara who even sent Walter Arensberg his own hand-drawn rendition of the Dada symbol.[iv] The American art critic Thomas Craven, discussing in 1925 the famous Forum Exhibition of Modern American Art of 1916, indicated his displeasure with the number of Jewish artists posing as Americans, and thought that Alfred Stieglitz, “a Hoboken Jew” and major modernist proselytizer was not fit to lead American art.[v]

Duchamp’s Fountain directly influenced Morton Schamberg who was born in Philadelphia to middle-class German Jewish parents, and Man Ray, who was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia to Russian Jewish immigrants. Arnason notes that “Relatively unburdened by tradition and always somewhat bumptious toward it” artists like Schamberg and Man Ray had “little difficulty entering into the Dada spirit”. Dempsey notes that “The delight in paradox and interaction of the visual and the verbal are also integral features of Schamberg’s blasphemous God (c. 1917), a plumbing trap on a box.”[vi] Schamberg was to die soon after producing God at the age of 37, a victim of the 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic.

Man Ray was to become a leading figure in the Dada movement. At age seven his father moved the family to Brooklyn to take a higher-paying job in a garment factory. Ray’s father also and ran a tailoring business, and his mother was a seamstress. At the suggestion of his brother the family changed its name to Ray in 1912, and from then onwards Man Ray signed his work with that name. In 1915 Walter Arensberg, a wealthy poet and patron of modern art, took Marcel Duchamp to meet Man Ray, and that same year Ray moved into Manhattan and became involved in the circle of avant-garde writers and intellectuals gathered around the Arenbergs.

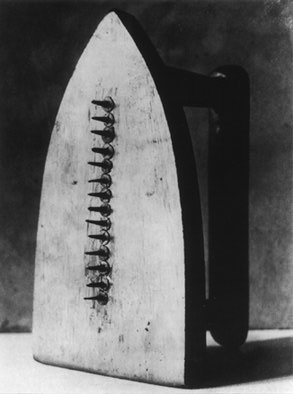

According to one source, Ray tried to disassociate himself from his Jewish family background, but he continued to use props with familiar significance: tailor’s dummies, flat irons, sewing machines, needles, pins, threads and swatches of fabric. An example of this is “Cadeau” (Gift), which is an iron with tacks attached to it. Instead of ironing clothing, Ray’s Cadeau promises to rip it to shreds.

Man Ray collaborated with Duchamp in in the publication of New York Dada in April 1921. This took the form of a large sheet of paper printed on one side only and folded twice. There were several articles, including one by Tzara, translated by Man Ray. However, by 1921 the atmosphere in New York had changed dramatically from wartime, and New York Dada was a flop. Several months after it appeared, Man Ray wrote to Tristan Tzara, complaining that “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada and will not tolerate a rival, will not notice Dada.”[vii] Most of the artists who had lived there had left the city, and Stieglitz had closed his gallery. Duchamp could no longer extend his residency permit for the United States and prepared to return to Paris where the Dada group had invited him to show his work at their June 1921 exhibition.

Man Ray arrived in Paris in July 1921, shortly after Duchamp, and remained there until 1940, becoming the youngest member of the Paris Dada group, and later of the Surrealists, even though his involvement in the new movement did not reflect any real modification of his art. With the arrival of Duchamp and Man Ray in Paris, New York Dada, which had not engaged in the kind of militant cultural protest seen in the European centers of Dada, effectively came to an end. Duchamp’s and Ray’s experiences were not dissimilar from that of many other Dadaists “who were swept along, as they were, by the vehemence of André Breton into the coils of the new Surrealist movement which was, in many ways, an offspring of Dada.”[viii] Man Ray became an established figure in the Parisian avant-garde, gaining fame and a good living with photographs of artists and art, as well as in fashion photography.

1940, becoming the youngest member of the Paris Dada group, and later of the Surrealists, even though his involvement in the new movement did not reflect any real modification of his art. With the arrival of Duchamp and Man Ray in Paris, New York Dada, which had not engaged in the kind of militant cultural protest seen in the European centers of Dada, effectively came to an end. Duchamp’s and Ray’s experiences were not dissimilar from that of many other Dadaists “who were swept along, as they were, by the vehemence of André Breton into the coils of the new Surrealist movement which was, in many ways, an offspring of Dada.”[viii] Man Ray became an established figure in the Parisian avant-garde, gaining fame and a good living with photographs of artists and art, as well as in fashion photography.

Dada in Germany

Early in 1917, Richard Huelsenbeck, a twenty-four-year-old German medical student and poet, returned to Berlin from Zurich, where he had spent the preceding year in the company of the Zurich Dadaists under the leadership of Tristan Tzara. After the war ended Dada activity in Germany increased as Dadaists dispersed to various sites throughout the country including, most prominently, Berlin, Cologne and Hanover. In Germany alongside George Grosz, Walter Mehring, Johannes Baader, Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters were several Jews, including Johannes Baargeld (1876–1955), Raoul Hausmann (1886–1971), and Eli Lissitzky (1890–1941).

The political radicalism of the Berlin Dadaists was even more pronounced than that of the Zurich or New York Dadaists; most of them belonged to the League of Spartacus, a radical socialist group that became the German Communist Party in 1919. German Dada was also closer than the others to developments in eastern Europe where a vigorous artistic avant-garde had existed before the war (led by Jews like Eli Lissitzky and László Moholy-Nagy). The new Soviet state that emerged after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917 adopted, at least initially, a policy in favor of radical experimentation. Gale notes how “in Berlin, more than anywhere outside the Soviet Union, a direct equation could be made between political reform and artistic radicalism. Despite the seeming absurdity of some of their activities, the Dadas’ reinvention of poetic language and artistic form could be seen as a prelude to reforming the whole of the decayed social system.”[ix]

In a new Dada Manifesto by Huelsenbeck and Hausmann, which was published in a Cologne newspaper, they enunciated the purposes of Dada: “Dada is German Bolshevism”[x]; “Dadaism demands: the international revolutionary union of all creative and intellectual men and women on the basis of radical Communism… The Central Council demands the introduction of the simultaneist poem as a Communist state prayer.”[xi] The Manifesto, parodying Woodrow Wilson’s fourteen points, also called for an international revolutionary union of all creative men and women; for progressive unemployment through the mechanization of all fields of activity; for the abolition of private property; for the provision of free daily meals for creative people and intellectuals; for the remodeling of city life by a Dadaist advisory council; and for the regulation of all sexual activity under the supervision of a Dadaist sexual center.[xii]

The Berlin Dadaists condemned the Weimar Republic as representing a renaissance of “Teutonic barbarity,” and held Communism to be the best hope for freedom.[xiii] The Berlin Dadaists were politically vocal and caused a stir not by formulating policies, but by fulfilling their self-appointed role to “react to the contemporary crisis, to seize the moment and to open people’s eyes through their provocative imagery and words which might indeed influence wider decisions.”[xiv] Short notes that among the German Dadaists were those for whom “Dada was a political weapon and those for whom Communism was a Dadaistical weapon. There was a faction which saw anarchy and anti-art as a sufficient programme in itself, and a second faction which saw anarchy as a provisional precondition for the introduction of new values.”[xv]

Falling into the latter category was Johannes Baargeld. Born Alfred Emanuel Ferdinand Gruenwald to a prosperous Romanian Jewish insurance director, Johannes Baargeld was the ironic, leftist pseudonym he adopted (‘Baargeld’ being the German word for cash or ready money). Baargeld grew up in Cologne in a wealthy home, and was exposed from a young age to contemporary art and culture, beginning with his parents’ collection of modernist paintings. He joined the Independent Socialist Party of Germany (USPD), which was the radical left wing of the Socialist Party, and in the process “turned his back on his wealthy bourgeois upbringing and became actively involved in the leadership of the Rhineland Marxists.”[xvi]

Baargeld (who was also called “Zentrodada”) and Max Ernst cofounded Dada in Cologne in the summer of 1919. Baargeld financed and collaborated with Max Ernst to produce Der Ventilator, a radical periodical which they distributed at factory gates before it came to the attention of the British censors and was promptly banned by the British Army of Occupation. This short lived journal, steeped in radical politics and aesthetics was “a signal moment in the formation of a brief but important avant-garde movement in Cologne.[xvii] According to Hans Richter, Baargeld’s father was anxious about his son’s political leanings and sought the help of Jean Arp and Max Ernst. Short notes that “They succeeded in convincing him that Dada went further than Communism and that its combination of new-found inner freedom and powerful external expression could do more to set the whole world free. In return, Grunewald senior financed the publication of a new international Dada magazine Die Schammade.”[xviii]

Although Baargeld’s initial contributions to Cologne Dada were in the form of political texts and poetry, he later ventured into visual art, preferring non-traditional media of collage, photomontage, assemblage and typography. In his work he subverted traditional systems of structure and logic by simultaneously imitating and undermining them in his artwork. In Ordinaire Klitterung: Kubischer Transvestit vor einem vermeintlichen Scheidewege (Vulgar Mess: Cubistic Transvestite at an Alleged Crossroads) Baargeld “deepens his critique of Western society’s patriarchal structures and founding myths” by conflating the “Greek myth of heroic Hercules at a moral crossroads with the odd drama of a cubistic transvestite.”[xix]

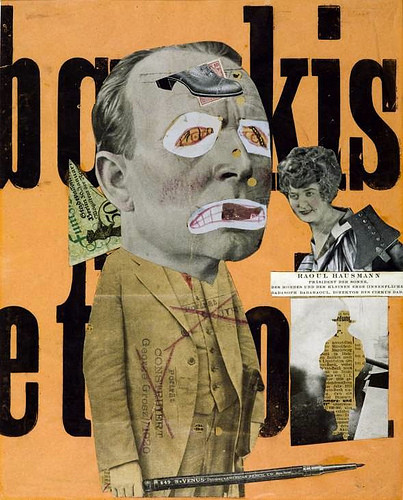

The leading Jewish Dadaist Raoul Hausmann, who was co-founder of Club Dada in Berlin, played a key role in organizing Dada events, including the First International Dada Fair, and numerous Dada matinees and soirées. Kriebel notes that “Hausmann understood himself to be a pioneer for the birth of the new man. The notion of destruction as an act of creation was the point of departure for Hausmann’s Dadasophy, his theoretical contribution to Berlin Dada.”[xx] Hausmann was one of the inventors of photomontage, making up pictures from scraps of photographs. Dada’s destruction/creation dialectic is well illustrated by this medium, and Hausmann’s own artistic contribution to Dada is well represented by photomontages like “The Art Critic.”

Schnapp notes that it was “the exponents of Berlin’s Dada that developed the expressive potential of the collage on a polemical and political level. In the creation of the photomontage, whether it was the invention of Hausmann and Höch or Grosz and Heartfield, it is implicit that its original purpose was propagandistic. The targets were, variously, the militaristic ruling class that lead Germany to war, the bigoted bourgeoisie, and the spirit of Weimar.”[xxi] For the Berlin Dadaists, the use of photographs and the technique of photomontage became primary tools in their work. They were influenced by the Futurists and the Russian avant-garde, whose artists “had wedded art to the Russian Revolution, and a faith in technology that held promise for their own communist future.”[xxii]

Dada in Hanover was inaugurated (and relabeled MERZ) by Kurt Schwitters who was the dominant proponent and practitioner of Dada in that city. Joining Schwitters at Hanover between 1922 and 1925 was the Russian Jewish artist El Lissitzky. Eliezer Markovich Lissitzky had illustrated the “Chad Gadya” and many Yiddish children’s books, and belonged to the Yiddish publishing house Kultur-Lige. Lissitzky’s main artistic activity before 1916 had been his involvement with a national movement to revive Yiddish secular culture in Russia. His endeavors in this cause gained particular momentum after the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917, an event which Hockensmith notes “resulted in the removal of all Tsarist restrictions on Jews.”[xxiii]

Lissitzky was closely associated with Constructivism which was viewed in the West as the art of the Bolshevik Revolution and associated with the functionalism of engineering. Lissitzky first came to Berlin as Soviet Cultural ambassador in 1921 and while there he actively promoted Constructivism. The desire on the part of the Soviet leadership for more efficient communication with the people brought increasing restrictions which encouraged many Constructionists to move to Germany in the 1920s. These included Lissitzky and the Hungarian Jewish artist László Moholy-Nagy, who were soon drawn into the orbit of the Bauhaus, the pioneering school of art and design at Weimar.

Lissitzsky met Schwitters at the Congress of Progressive Artists in Weimar in 1921 and was invited to Hanover. While Lissitzky initially criticized Dada as anachronistic, and in a review complained that Schwitters was not advancing beyond his artistic beginnings, the two soon formed a collaboration that would last from 1922 until Lissitzky returned to the Soviet Union in 1925. Lissitzky pushed Schwitters work toward a more constructivist style of geometric shapes and gridded compositions. Meanwhile Lissitzky was prompted by the Dadaist sensibility “to accommodate the irrational and the organic within his predominantly technophilic philosophy.”[xxiv] Gale makes the point that “The Constructivists and Dadas shared political beliefs in the imminent triumph of the proletariat over the decayed bourgeoisie of the West.”[xxv]

In April 1920, Cologne Dada staged one of the most memorable exhibitions of the entire movement. It was mounted in the courtyard of the Winter Brewery and could only be entered by way of a public lavatory. Among the “exhibits” in this “Dada Spring Awakening” was a young girl in communion dress reciting obscene verses, Ernst’s destructible object with an axe beside it and an invitation to hack at it, and a bizarre object by Baargeld consisting of an aquarium filled with red fluid from which protruded a polished wooden arm and on whose surface floated a head of woman’s hair.[xxvi] The First International Dada Fair was held in Berlin on 5 June 1920, and remained the most significant artistic event organized in the Berlin milieu. The radical political orientation of the organizers was illustrated by the mannequin of a German officer with the head of a pig hanging from the ceiling (with a notice “Hanged by the revolution”), which triggered fierce debate with its subversive and anti-military character.”[xxvii]

Dadaists at the First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920. A mannequin of a German officer with the head of a pig hangs from the ceiling

Given such provocative gestures and the integral and extensive Jewish participation in Dada, it was hardly surprising that, between the two world wars, German nationalists linked Dada and avant-gardism generally to Judaism, claiming these modern trends aimed to destroy the principles of classical beauty and eradicate national traditions. The Dadaists were said to express the “nihilistic Jewish spirit” (a common phrase at the time) if they were not actually mad. In response to the activities of Jewish Dadaists, “calls for ‘degenerate’ art to be banned were widely published in pre-Nazi and later in Nazi Germany, as well as in France.”[xxviii]

Interestingly, Hitler’s Mein Kampf was written just as Dada hit a peak in Paris, and Hitler’s comments about Jewish influence on Western art need be understood in this context. He discusses the “artistic aberrations which are classified under the names of Cubism and Dadaism,” and clearly has the Dadaists in mind when he observes that: “Culturally, his [the Jew’s] activity consists in … holding the expressions of national sentiment up to scorn, overturning all concepts of the sublime and the beautiful, the worthy and the good, finally dragging the people to the level of his own low mentality.”[xxix] Likewise when he recalls how he once asked himself whether “there was any shady undertaking, any form of foulness, especially in cultural life, in which at least one Jew did not participate?” Subsequently he discovered that “On putting the probing knife carefully to that kind of abscess one immediately discovered, like a maggot in a putrescent body, a little Jew who was often blinded by the sudden light.”[xxx]

In 1933 Hitler’s new government announced that “The custodians of all public and private museums are busily removing the most atrocious creations of a degenerate humanity and of a pathological generation of ‘artists’. This purge of all works marked by the same western Asiatic stamp has been set in motion in literature as well with the symbolic burning of the most evil products of Jewish scribblers.”[xxxi]

At the exhibition of degenerate art held in Munich in 1937, Dadaist works were considered the most degenerate of all – the very epitome of Kulturbolschewismus. In that year the Ministry for Education and Science published a pamphlet in which Dr Reinhold Krause, a leading educator, wrote that “Dadaism, Futurism, Cubism, and other isms are the poisonous flower of a Jewish parasitical plant.”[xxxii]

Paul Johnson points out that “Hitler always referred to degenerate art as ‘Cubism and Dadaism’, maintaining that it started in 1910, and the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition bore a curious resemblance to the big Dada shows of 1920–22, with a lot of writing on the walls and paintings hung without frames.”[xxxiii] He also notes that the National Socialist campaign against “degenerate art” was “the best thing that could possibly have happened, in the long term, to the Modernist Movement.” This is because since the National Socialists—universally reviled by all governments and cultural establishments since 1945—tried to destroy and suppress such art completely, then its merits were self-evident; anything the Nazis opposed was assumed to have merit – on the illogical basis that the enemy of my enemy must be my friend. “These factors,” notes Johnson, “so potent in the second half of the twentieth century, will fade during the twenty-first, but they are still determinant today.”[xxxiv]

Go to Part 4.

REFERENCES

Adam, P. (1992) Arts of the Third Reich, Harry N. Abrams, New York.

Ades, D. (1974) ‘Dada and Surrealism,’ In Modern Art – Impressionism to Post-Modernism, Ed. By David Britt, Thames & Hudson, London.

Bernard, E. (2004) Modern Art – 1905-1945, Chambers, Paris.

Blisténe, B. (2001) A History of Twentieth Century Art, Fammarion, Paris.

Cabanne, P. (1997) Duchamp & Co., Finest SA/Editions Pierre Terrail, Paris.

Dagen, P. (2011) ‘From Dada to Surrealism – Review,’ The Guardian, July 19. View at: http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jul/19/dada-to-surrealism-dagen-review

Dempsey, A. (2002) Styles, Schools and Movements – An Encylopaedic Guide to Modern Art, Thames & Hudson, London.

Doherty, B. (2005) ‘Berlin,’ In: Dada Ed. By Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Gale, M. (2004) Dada & Surrealism, Phaidon, London.

Hitler, A. (2010) Mein Kampf (trans. By James Murphy), Imperial Collegiate Publishing.

Hockensmith, A. (2005) ‘Artists’ Biographies,’ In Dada Ed. By Leah Dickerman, Dada, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Johnson, P. (2003) Art – A New History, HarperCollins, New York.

Kriebel, S.T. (2005) ‘Cologne,’ In: Dada Ed. By Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

Leslie, R. (2005) Surrealism – The Dream of Revolution, New Line Books, London.

Russell, J. (1981) The Meanings of Modern Art, Thames & Hudson, London.

Schnapp, J.T. (2006) ‘The Dada revolution’ In: Art of the Twentieth Century – 1900-1919 The Avant-garde Movements, Skira, Italy.

Short, R. (1994) Dada and Surrealism, Laurence King Publishing, London.

Taylor, M.R. (2005) ‘New York,’ In: Dada Ed. By Leah Dickerman, National Gallery of Art, Washington D.C.

ENDNOTES

[i] Taylor p. 287

[ii] Cabanne p. 115

[iii] Taylor p. 278

[iv] Ibid. p. 281

[v] Washton-Long et al. p. 6

[vi] Dempsey p. 118

[vii] Hockensmith p. 479

[viii] Schnapp p. 412

[ix] Gale p. 120

[x] Blisténe p. 62

[xi] Ades p. 222

[xii] Russell p. 182

[xiii] Bernard p. 86

[xiv] Gale p. 121

[xv] Short p. 42

[xvi] Doherty p. 220

[xvii] Ibid.

[xviii] Short p. 47

[xix] Kriebel p. 229

[xx] Ibid. p. 472

[xxi] Schnapp p. 409

[xxii] Leslie p. 39-40

[xxiii] Hockensmith p. 478

[xxiv] Ibid.

[xxv] Gale p. 158

[xxvi] Short p. 50

[xxvii] Schnapp p. 399

[xxviii] Dagen

[xxix] Hitler p. 281

[xxx] Ibid. p. 58

[xxxi] Adam p. 55

[xxxii] Ibid. p. 12-15

[xxxiii] Johnson p. 707

[xxxiv] Ibid. p. 709

Comments are closed.