Evil Genius: Constructing Wagner as Moral Pariah, Part 2

Part 2: Jewish Responses to Wagner’s Ideas

Basically ignoring whether Wagner’s views on Jewish influence on German art and culture had any validity, a long line of Jewish music writers and intellectuals have furiously attacked the composer for having expressed them. In his essay “Know Thyself” Wagner writes of the fierce backlash that followed his drawing “notice to the Jews’ inaptitude for taking a productive share in our Art,” which was “met by the utmost indignation of Jews and Germans alike; it became quite dangerous to breathe the word ‘Jew’ with a doubtful accent.” Wagner’s critique of Jewish influence on German art and culture could not be dismissed as the ravings of an unintelligent and ignorant fool. Richard Wagner was, by common consent, one of the most brilliant human beings to have ever lived, and his views on the Jewish Question were cogent and rational. Accordingly, Jewish critics soon settled on the response of ascribing psychiatric disorders to Wagner, and this has been a stock approach ever since. As early as 1872 the German Jewish psychiatrist Theodor Puschmann, offered a psychological assessment of Wagner which was widely reported in the German press. He claimed that Wagner was suffering from “chronic megalomania, paranoia… and moral derangement.”

The long-time music critic for the New York Times, Harold Schonberg (who was a Jew), described Wagner in his Lives of the Great Composers (1997) as “amoral, hedonistic, selfish, virulently racist, arrogant, filled with gospels of the superman … and the superiority of the German race, he stands for all that is unpleasant in human character.” In 1968 the Jewish writer Robert Gutman published a biography of Wagner (Richard Wagner: the Man, his Mind and his Music) in which he portrayed his subject as a racist, psychopathic, proto-Nazi monster. Gutman’s scholarship was questioned at the time, but this did not prevent his book from becoming a best-seller, and as one source notes: “An entire generation of students has been encouraged to accept Gutman’s caricature of Richard Wagner. Even intelligent people, who have either never read Wagner’s writings or tried to penetrate them and failed … have read Gutman’s book and accepted his opinions as facts.”

Another prominent refrain from Jewish commentators like Jacob Katz, the author of The Darker Side of Genius: Richard Wagner’s Anti-Semitism, is that Wagner’s concern about the Jewish influence on German culture stemmed from his jealousy at the brilliant Jews around him like Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer and Heine. Taking up this theme, the music writer David Goldman insists that: “Wagner ripped off the scenario for his opera “The Flying Dutchman” from Heine and knocked off Mendelssohn’s “Fingal’s Cave” overture in the “Dutchman’s” evocation of the sea. Wagner tried to cover his guilty tracks by denouncing Jewish composers he emulated, including Giacomo Meyerbeer. Wagner was not just a Jew-hater, then, but a backstabbing self-promoter who defamed the Jewish artists he emulated and who (in Meyerbeer’s case) had advanced his career.” Boroson, writing in the Jewish Standard, likewise asserts that Wagner’s envy of Meyerbeer’s success “played a pivotal role in Wagner’s suddenly becoming a Jew-hater.”

Invoking Freud and the Frankfurt School, the Jewish music writer Marc A. Weiner in his Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination, claims that “Wagner’s vehement hatred of Jews was based on a model of projection involving a deep-seated fear of precisely those features within the Self (diminutive stature, nervous demeanour and avarice, as well as lascivious nature) that are projected upon and then recognized and stigmatized in the hated Other.” (p. 6) Weiner’s view echoes that of Theodore Rubin who views anti-Semitism as a “symbol sickness” that involves “envy, low self-esteem and projection of one’s inner conflicts onto a stereotyped other.” All these various theories, where Wagner’s criticism of Jewish influence is made entirely a scapegoat for his own psychological frustrations, vastly overemphasize the irrational sources of prejudice and effectively serve, as Higham put it, to “clothe the Jews in defensive innocence.” (p. 58) According to these theories, anti-Jewish sentiment is never rational, but invariably the product of a warped mind, while Jewish critiques of Europeans and their culture always have a rational basis.

Invoking Freud and the Frankfurt School, the Jewish music writer Marc A. Weiner in his Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination, claims that “Wagner’s vehement hatred of Jews was based on a model of projection involving a deep-seated fear of precisely those features within the Self (diminutive stature, nervous demeanour and avarice, as well as lascivious nature) that are projected upon and then recognized and stigmatized in the hated Other.” (p. 6) Weiner’s view echoes that of Theodore Rubin who views anti-Semitism as a “symbol sickness” that involves “envy, low self-esteem and projection of one’s inner conflicts onto a stereotyped other.” All these various theories, where Wagner’s criticism of Jewish influence is made entirely a scapegoat for his own psychological frustrations, vastly overemphasize the irrational sources of prejudice and effectively serve, as Higham put it, to “clothe the Jews in defensive innocence.” (p. 58) According to these theories, anti-Jewish sentiment is never rational, but invariably the product of a warped mind, while Jewish critiques of Europeans and their culture always have a rational basis.

Another well-worn theory has it is that Wagner may have been part-Jewish, and that his “rabid anti-Semitism” was his way of dealing this unedifying prospect (a variation of the “self-hating Jew” hypothesis). It is claimed that Wagner’s biological father was not his presumed father, Friedrich Wagner, but his stepfather, the successful actor and painter Ludwig Geyer. However, there is no evidence that Geyer had any Jewish roots. In his biography of the composer, John Chancellor states categorically that he had none, and that: “He [Geyer] claimed the same sturdy descent as the Wagners. His pedigree also went back to the middle of the seventeenth century and his forefathers were also, for the most part, organists in small Thuringian towns and villages.” (p. 6)

Chancellor blames Friedrich Nietzsche for first raising the question of Geyer’s possible Jewishness to add extra sting to his charge of illegitimacy, after the philosopher famously fell out with Wagner. In his 1888 book Der Fall Wagner (The Case of Wagner) Nietzsche claimed that Wagner’s father was Geyer, and made the pun that “Ein Geyer ist beinahe schon ein Adler” (A vulture is almost an eagle) — Geyer also being the German word for a vulture and Adler being a common Jewish surname. Despite these conjectures on the part of Nietzsche and then legions of music historians and biographers, there is no evidence that Ludwig Geyer was Jewish.

The lack of evidence did not deter Gutman, however, who contended that Richard Wagner and his wife Cosima tried to outdo each other in their anti-Semitism because they both had Jewish roots to conceal. While offering no proof that Geyer was Jewish, Gutman maintained that Wagner in his later years discovered letters from Geyer to his mother which led him to suspect that Geyer was his biological father, and thought that Geyer might have been Jewish. Wagner’s anti-Semitism was, according to Gutman, his way of dealing with the fear that people would think he was Jewish. Strahan recycles this theme in a recent article, noting that:

Geyer’s affair with Wagner’s mother pre-dated the death of Wagner’s presumed father, Friedrich Wagner, a Police Registrar who was ill at the time young Richard was conceived, and who died six months after his birth. Soon after this, Wagner’s mother Johanna married Ludwig Geyer. Richard Wagner himself was known as Richard Geyer until, at the age of 14, he had his name legally changed to Wagner. Apparently he had taken some abuse at school because of his Jewish-sounding name. Could his later anti-Semitism have been motivated, at least in part, by sensitivity to this abuse, and by a kind of pre-emptive denial to prevent difficulties and suffering arising from prejudice?

According to the only evidence we have on this point (Cosima’s diaries, 26 December 1868) Wagner “did not believe” that Ludwig Geyer was his real father. Cosima did, however, once note a resemblance between Wagner’s son Siegfried and a picture of Geyer (p. 1). Pursuing the theme that anyone who expresses antipathy toward Jews must be psychologically unhealthy, Larry Solomon draws a parallel between Wagner and Adolf Hitler in that “Both feared they had Jewish paternity, which led to fierce denial and destructive hatred.”

Wagner’s Music Dramas as Coded Anti-Semitism

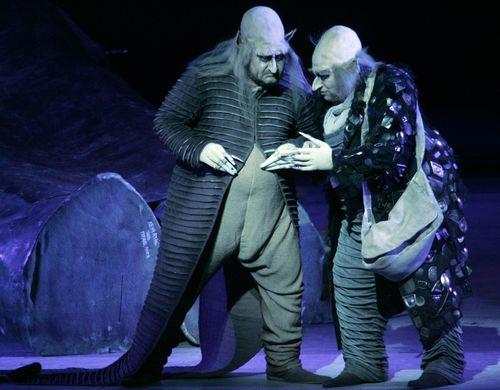

T.W. Adorno and Robert Gutman began a modern Jewish intellectual tradition when they proposed that Wagner’s antipathy to Jews was not limited to articles like Judaism in Music, but that there are hidden anti-Semitic and racist messages in Wagner’s operas. Numerous Jewish writers have taken up this theme and encouraged audiences to retrospectively read into Wagner’s operas latent signs of anti-Semitism. The gold-loving Nibelung lord Alberich in Siegfried is, for instance, supposedly a symbol of Jewish materialism. Solomon writes that Alberich is clearly “the greedy merchant Jew, who becomes the power-crazed goblin-demon lusting after Aryan maidens, attempting to contaminate their blood, and who sacrifices his lust in order to acquire the gold.”

Viktor Chernomortsev, left, as Alberich and Vasliy Gorshkov as Mime in the Kirov Opera production of Wagner's "Siegfried" at the Orange County Performing Arts Center in 2006.

In The Mastersingers of Nuremburg, Beckmesser, who is incapable of original work and resorts to stealing the work of others, is said to symbolize the lack of Jewish originality that Wagner highlighted in Judaism in Music. According to Gutman, Beckmesser was modeled after Eduard Hanslick, the powerful half-Jewish music critic who constantly disparaged Wagner. The characters of Mime in the Ring and Klingsor in Parsifal are also identified as Jewish stereotypes, although none of these were actually identified as Jews by Wagner in the libretto. Mime is, for Solomon, depicted by Wagner “as a stinking ghetto Jew” while “Siegfried represents the conscience-free, fearless Teuton, he feels no remorse… He is glorified as the warrior hero of the Ring, the archetypal proto-Nazi.”

Solomon is unconcerned at the lack of any real evidence for his thesis, maintaining that virulent racism “permeates all aspects of his music dramas through metaphorical suggestion. Wagner is always just a step away from actually calling his evil characters ‘Jews’, even though it was obvious to his contemporaries.” He claims that Wagner was too clever to identify Jews in his music dramas, especially after he had received critical reactions to his essay Judaism in Music. “His intent was far more artful and covert, but nevertheless still political: to reach his audience on an emotional, subliminal level, bypassing their critical faculties.” In the final analysis, Wagner’s operas are for Solomon “tools of racist, proto-Nazi hate propaganda, written for the purpose of redeeming the German race from Jewish contamination, and for expelling the Jews from Germany.” Moreover, the malign influence of Wagner sadly continues insofar as “the subtext of racist metaphors has not diminished in Wagner’s operas, so they will continue to exert a subliminal influence.”

In his book Richard Wagner and the Anti-Semitic Imagination (1997) Marc A. Weiner similarly argued that Wagner deliberately used his characters to promote his sociological theories of a pure Germany purged of Jewish influence. According to Weiner:

Wagner’s anti-Semitism is integral to an understanding of his mature music dramas. … I have analyzed the corporeal images in his dramatic works against the background of 19th-century racist imagery. By examining such bodily images as the elevated, nasal voice, the “foetor judaicus” (Jewish stench), the hobbling gait, the ashen skin color, and deviant sexuality associated with Jews in the 19th century, it’s become clear to me that the images of Alberich, Mime, and Hagen [in the Ring cycle], Beckmesser [in Die Meistersinger], and Klingsor [in Parsifal], were drawn from stock anti-Semitic clichés of Wagner’s time.

For Weiner, Wagner’s anti-Semitic caricatures can be readily identified from their manner of speech, their singing, their roles, and their body language. “All of the stereotypical cardboard, cookie-cutter features of a Jew … show up all over the place in his musical dramas.” Under Weiner’s deconstruction of Wagner’s characters it emerges that his Teutonic heroes are “invariably clear-eyed, deep-voiced, straight-featured and sure-footed. The Jewish anti-heroes have dripping eyes, high voices, bent, crooked bodies and a hobbling, awkward step, with these embodied metaphors all serving to reinforce the ideology of racism.” In response to Weiner’s critique one is reminded of the aptness of historian Goldwin Smith’s remark that “critics of Judaism are accused of bigotry of race, as well as bigotry of religion. This accusation comes strangely from those who style themselves the Chosen People, make race a religion, and treat all races except their own as Gentile and unclean.” (p. 56)

Numerous Jewish commentators cite Wagner’s Parsifal, the last of his music dramas, as “possibly his most racist opera.” For the Jewish writer Paul Lawrence Rose, in his 1992 book Wagner, Race and Revolution, Wagner intended his Parsifal to be

a profound religious parable about how the whole essence of European humanity had been poisoned by alien, inhuman, Jewish values. It is an allegory of the Judaization of Christianity and of Germany — and of purifying redemption. In place of theological purity, the secularized religion of Parsifal preached the new doctrine of racial purity, which was reflected in the moral and indeed religious, purity of Parsifal himself. In Wagner’s mind, this redeeming purity was infringed by Jews, just as devils and witches infringed the purity of traditional Christianity. In this scheme, it is axiomatic that compassion and redemption have no application to the inexorably damned Judaized Klingsor and hence the Jews. (p. 166)

Jewish music critics and intellectuals, like those cited above, have enthusiastically seized upon Wagner’s great grandson Gottfried for having backed their various theories about the inherently anti-Semitic nature of Wagner’s operas, and Wagner’s firm standing as a moral

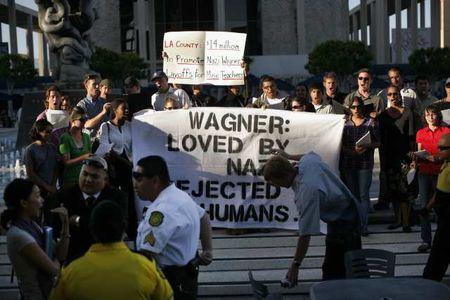

pariah. Gottfried Wagner has made a virtual career out of relentlessly attacking his ancestors — constantly denouncing his great-grandfather and other family members as evil anti-Semites. In his 1999 book, Twilight of the Wagners: The Unveiling of a Family’s Legacy, Gottfried Wagner, according to Solomon, “in an act of self-imposed moral obligation and great personal sacrifice, restored to his roots the conscience that Wagner and Hitler took away.” To the great satisfaction of Carol Jean Delmar (the Jewish leader of a campaign to have the LA Opera’s 2009 production of the Ring cancelled), the philo-Semitic Gottfried Wagner appeared at a symposium at the American Jewish University in 2010 where he continued “to set the record straight today. Always on the side of the Jews, he stopped off on Shabbos to mingle with congregants at a local temple.”

Despite all the claims made about the anti-Semitic nature of Wagner’s operas, Strahan points out that it is equally possible to point to cultural references in Wagner’s work that are sympathetic to the Jewish place in European culture. For Strahan, “the hero of the early opera The Flying Dutchman is synonymous with the ‘Wandering Jew,’ the Dutchman’s endless journeying analogous to that symbol of the Jewish Diaspora.” Wagner himself referred to his eminently non-Jewish personification of redemption through love, the Flying Dutchman, as an “Ahasverus of the Ocean.”

Wagner produced thousands of pages of written material analyzing every aspect of himself, his operas, and his views on Jews (as well as many other topics); and yet the purportedly “Jewish” characterizations identified by Adorno, Gutman and countless others are never mentioned, nor are there any references to them in Cosima Wagner’s copious diaries. None of Wagner’s supposedly obvious characterizations were ever used in the propaganda of the Third Reich.To identify such characters as Beckmesser, Alberich, Mime, Klingsor and Kundry as Jews is thus entirely speculative. The Jewish pianist and conductor Daniel Barenboim makes the point that: “Whoever wants to see a repulsive attack on Jews in Wagner’s operas can of course do so. But is it really justified? Beckmesser, for example, who might be suspected of being a Jewish parody, was a state scribe in the year 1500, a position that was unavailable to Jews.”

Wagner and National Socialist Germany

Wagner has long been reviled by Jews as the intellectual and spiritual precursor to Adolf Hitler, who according to William Shirer, once declared “Whoever wants to understand National Socialist Germany must know Wagner.” This line is spoken by the Hitler character in the 2008 Hollywood film Valkyrie. For Solomon, no other composer in history had a greater impact on world events than Richard Wagner; and that “his devastating political legacy is second only to Adolf Hitler.” In his book Anti-Semitism: A Disease of the Mind: A Psychiatrist Explores the Psychodynamics of a Symbol Sickness, Theodore Isaac Rubin states categorically that a psychologically sick Adolf Hitler “borrowed from the almost equally sick anti-Semitic Wagner.”

This widely accepted notion of a direct intellectual line of descent from Wagner to Hitler has, however, been challenged by the historian Richard Evans (a key witness on behalf of Deborah Lipstadt in her defense against the libel suit brought by David Irving) who pointed out that there is no evidence that Hitler even read any of Wagner’s writings. In the early twentieth century these writings were rarely reprinted or discussed outside of academic circles. Hitler seldom mentioned Wagner in his own writings, and rarely in public, and when he did, it was never in relation to Jews, but rather to his standing as a German leader and visionary. Wagner’s influence on Hitler was at best secondhand through the influence of his son-in-law Houston Stewart Chamberlain, who developed some of Wagner’s ideas in his bestselling 1899 book The Foundations of the Nineteenth Century, which did influence Hitler’s ideas on race and the Jewish Question. Despite the lack of a direct intellectual link between Wagner and Hitler, for the Jewish music writer David Goldman, Wagner’s name is eminently worthy of execration on the basis that he “mixed the compost heap in which the flowers of the 20th century’s greatest evil took root.” According to Goldman,

the Nazis embraced Wagner not by accident or opportunism but because they recognized in him the cultural trailblazer of the world they set out to rule. … Wagner may not have been the only anti-Semite among the composers of the 19th century, nor even the worst, but he did more than anyone else to mold the culture in which Nazism flourished. The Jewish people have had no enemy more dedicated and more dangerous, precisely because of his enormous talent. In a Jewish state, the public has a right to ask Jewish musicians to be Jews first and musicians second. With reluctance, and in cognizance of all the ambiguities, I think the Israelis are right to silence him. [Goldman here refers to the unofficial ban on performances of Wagner’s music in Israel]

For Goldman, Hitler’s intellectual debt to Wagner and the “proto-Nazi” nature of Wagner’s music dramas are unambiguous. Nevertheless, Evans dismisses the notion that Wagner’s works inherently support National Socialist notions of heroism, and notes that Wagner’s last opera Parsifal (frequently cited as Wagner’s most “racist” opera) was denounced by the regime in 1933 for being “ideologically unacceptable” and was not performed at Bayreuth during the war. Moreover, while Wagner’s music was often performed during the Third Reich, his popularity in Germany actually declined in favor of Italian composers like Verdi and Puccini. Evans notes that by the 1938–39 opera season, Wagner had only one opera in the top fifteen most popular operas of the season, with the list being headed by Leoncavallo’s Pagliacci. (p. 198–201)

It is well known that The Berlin Philharmonic’s last performance prior to their evacuation from Berlin in April 1945 was of Brünnhilde’s immolation scene at the end of Wagner’s Götterdämmerung to an audience that included Speer, Dönitz and Goebbels. This music has since been used in countless Third Reich documentaries — in the process consolidating the impression that Wagner’s music was uniquely bound up with the cultural politics of the National Socialist state. Although, as noted above, there is no evidence that Hitler’s attitudes on Jews derived from Wagner, it is clear that the National Socialist fascination with Wagner (to the extent it genuinely existed) was Hitler’s inspiration. In one of three brief references to Wagner in Mein Kampf, Hitler reflects on his early experiences attending Wagner’s operas: “I was captivated. My youthful enthusiasm for the master of Bayreuth knew no bounds. Again and again I was drawn to his works, and it still seems to me especially fortunate that the most modest provincial performance left me open to an intensified experience later on.” Hitler became a friend of Wagner’s children and grandchildren, and particularly of his English-born daughter-in-law Winifred. In 1933 he ordered that each Nuremberg Rally would open with a performance of the Meistersinger overture, though these performances were mostly unpopular with other Party functionaries who had be ordered to attend.

Guido Fackler claims that Wagner’s music was sometimes used at the Dachau concentration camp in 1933 and 1934 to “reeducate” political prisoners through the beneficial exposure to nationalistic music. There is, however, no documentary evidence supporting the widespread claims that Wagner’s music provided “a soundtrack to the Holocaust,” and was played at concentration camps during wartime.Larry David mocked this urban legend (and the unhealthy Jewish obsession with Wagner) in an episode of Curb Your Enthusiasm where he is rebuked by a Jewish stranger for whistling a Wagner tune in the street (see here).

The ethno-political motivation that underpins the construction of Wagner as moral pariah is highlighted by the contrasting way that Jewish commentators have reflected on the life and legacy of the Jewish composer Hanns Eisler who declared Wagner to be “a great composer, unfortunately.” A committed Marxist, Eisler began in 1930 a long-standing collaboration with the poet and playwright Bertolt Brecht. With Hitler’s ascent to power, Eisler left Germany and eventually settled in Hollywood, where he was nominated for Oscars for writing the music for Fritz Lang’s film Hangmen Also Die (1942) and None But the Lonely Heart (1944). In 1947 Eisler appeared before the Un-American Activities Committee, and despite the intercession of Albert Einstein, Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein, was deported to East Germany in 1948 where he remained for the rest of his life, writing music for the totalitarian state (including its national anthem, and the Comintern anthem). Eisler collaborated with Adorno in 1947 to produce the book Composing for the Films. Instead of reproaching Eisler for his ardent commitment to a regime and an ideology that destroyed millions of lives, Jewish commentators have invariably portrayed him as a victim of the anti-Semitism of the Third Reich, and then of the HUAC hearings and the Hollywood blacklist.

The Jewish-dominated intellectual and media elite will ensure that next year’s Wagner bicentenary is overshadowed by claims that, in celebrating Wagner, the world is cruelly denying the unique suffering of the Jewish people. The bicentenary will provide a platform for advancing the anti-White narrative by using Wagner’s life and legacy as a salutary lesson on the evils of anti-Semitism and European nationalism. The construction of Wagner as an anti-Semitic exemplar and moral pariah (a form of ethnic warfare through the construction of culture) benefits Jews in several ways. First, it ensures that a White genius like Wagner (whose achievement far surpasses that of any Jewish composer) can never become a locus of White racial pride and group cohesion. Secondly, it ensures that Wagner and his works can be always used as a springboard for intensive reflections on the Holocaust, the evils of White racial identity and the moral necessity of state-sponsored multiculturalism and non-White immigration to the West. Only these policies, after all, will ensure that Wagner’s “morally loathsome” intellectual legacy (which amounts to a proposal for a group strategy in opposition to Judaism) can never again find a receptive White audience, by progressively doing away with white people altogether.

Comments are closed.