M. R. James and Saki: Two Literary Greats and their Anti-Semitism

Megalomaniacs dream of ruling the world. Philosophers dream of understanding it — ideally from an armchair. Armchair-understanding is what I’m going to attempt in this article. After all, armchairs are good places for reading. I want to take two short stories by famous English writers and use them to address an important question: Do Jews seek to control gentile societies for their own ends?

Serpents and Waspes

This is also a dangerous question. Any Westerner who answers it in the affirmative will certainly lose his reputation and might lose his income and liberty too. These negative consequences prove the wickedness of the proposition, of course, and not its truth. Or do they? The writers M.R. James (1862–1936) and Saki, born Hector Hugh Munro (1870–1916), might have said otherwise. Each of them was responsible for poisoning the well of English literature with doses of anti-Semitism, which is sometimes called the Longest Hatred.

Painting by Burne-Jones for “The Prioress’s Tale”

It’s called that with good reason: the well had already been poisoned for centuries when those two writers were born. Geoffrey Chaucer (c. 1342–1400) is known as the “Father of English Literature” and was the author of The Canterbury Tales, which dates from about 1380. He wrote in “The Prioress’s Tale” of a pious Christian child ritually murdered by Jews at the instigation of “the serpent Sathanas,/That hath in Jewes herte his waspes nest … .” (see modern version) In the tale, a miracle reveals the crime to the grieving mother and the Jews responsible are hanged. Chaucer concludes his hate-narrative with a prayer to “yonge Hugh of Lyncoln, slayn also/With cursed Jewes.”

Montague’s Malice

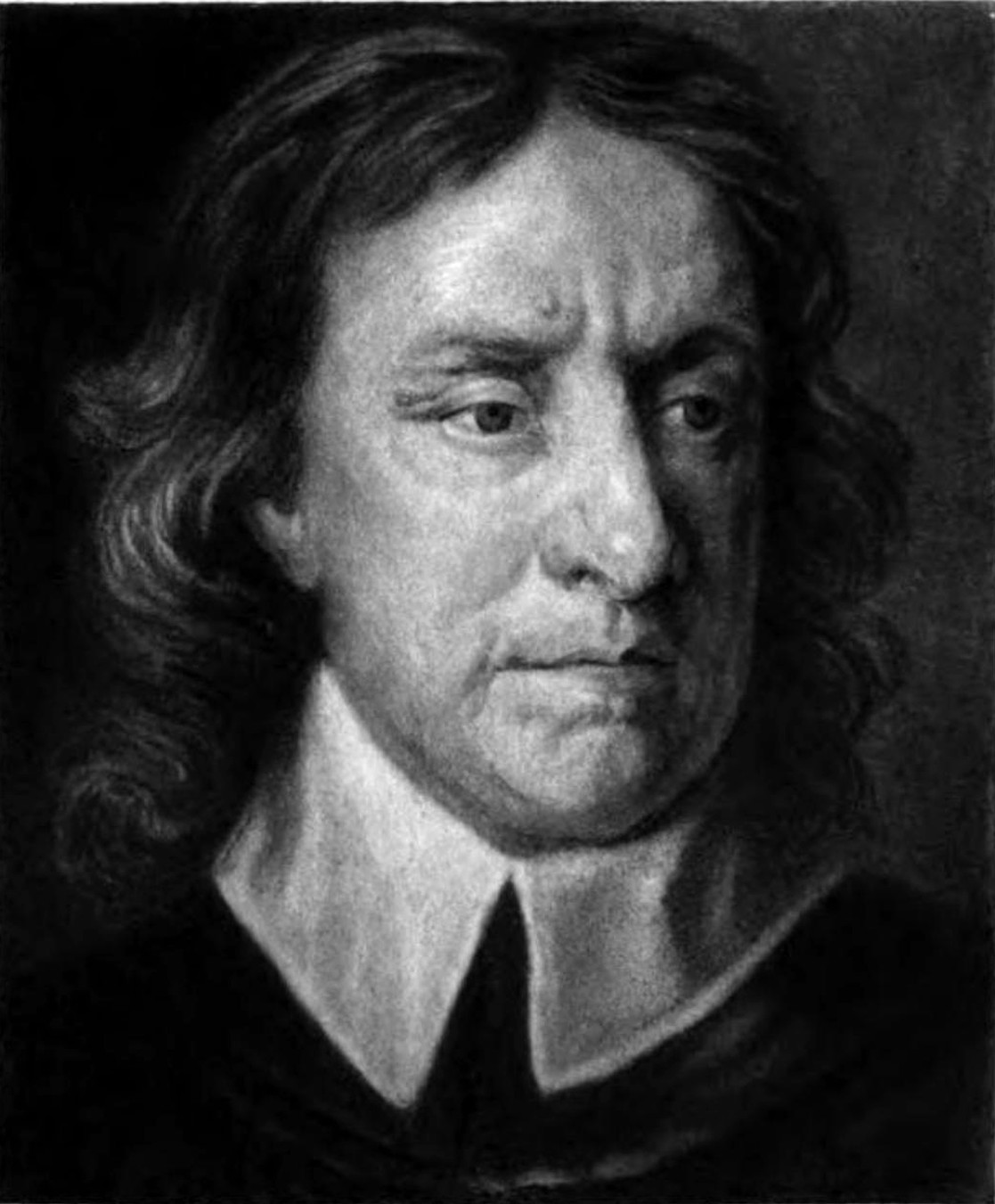

Six centuries later, the same anti-Semitism was festering in the work of the Christian scholar Montague Rhodes James, better known as M.R. James and acknowledged today as one of the world’s greatest writers of ghost-stories. He combined both scholarship and subtlety to conjure some of the most memorable and unpleasant spooks and phantasms ever to chill the spine of an armchair-reader. “The Uncommon Prayer-Book” (1921) is not one of his best or most famous stories, but is one of his most interesting. It describes an antiquary called Mr. Davidson who discovers a unique set of prayer-books at a remote country-house called Brockstone Court. The books were printed clandestinely during the despotism of Oliver Cromwell (1599-1658), who had banned the Anglican rites they contain, and now lie in an unused but regularly cleaned chapel.

M.R. James (1862-1936)

–

However, year after year the countrywoman who cleans the chapel has found the books mysteriously opened to “Psalm CIX.” It seems to happen on 25th April when the chapel is locked and deserted, so she cannot understand what is going on. Mr Davidson recognizes that this “savage psalm” is “a very odd and wholly unauthorized addition to the text.” After all, it’s a Jewish malediction that sits uncomfortably with the forgiveness and forbearance preached by Christianity:

109:2 For the mouth of the wicked and the mouth of the deceitful are opened against me: they have spoken against me with a lying tongue.

109:3 They compassed me about also with words of hatred; and fought against me without a cause. …

109:6 Set thou a wicked man over him: and let Satan stand at his right hand.

109:7 When he shall be judged, let him be condemned: and let his prayer become sin.

109:8 Let his days be few; and let another take his office.

109:9 Let his children be fatherless, and his wife a widow.

109:10 Let his children be continually vagabonds, and beg: let them seek their bread also out of their desolate places.

109:11 Let the extortioner catch all that he hath; and let the strangers spoil his labour.

109:12 Let there be none to extend mercy unto him: neither let there be any to favour his fatherless children.

109:13 Let his posterity be cut off; and in the generation following let their name be blotted out. (Psalm CIX in the King James Bible)

Furthermore, April 25th is Oliver Cromwell’s birthday and Brockstone Court was owned in his day by a fervent royalist called Lady Sadleir. Davidson wonders what “curious evil service” was being celebrated there during Cromwell’s reign. He resolves to return the following year on the date and investigate the mystery further.

Meet Mr. Homberger

But when he does so, accompanied by a friend, he finds that the prayer-books have been stolen since his previous visit. What has happened? Well, on that visit, Mr. Davidson stayed in a hotel and met “a small man in a fur coat,” “black-haired and pale-faced, with a little pointed beard, and gold pince-nez.” The man also has “a rather yapping foreign accent” and turns out to be a dealer in rare books:

[T]he dealer, whose name was Homberger, admitted that he was interested in books, and thought there might be in these old country-house libraries something to repay a journey. “For,” said he, “we English have always this marvellous talent for accumulating rarities in the most unexpected places, ain’t it?”

And in the course of the evening he was most interesting on the subject of finds made by himself and others. “I shall take the occasion after this sale to look round the district a bit; perhaps you could inform me of some likely spots, Mr. Davidson?”

But Mr. Davidson, though he had seen some very tempting locked-up book-cases at Brockstone Court, kept his counsel. He did not really like Mr. Homberger.

The Bibliophile Bit

Mr. Davidson’s instincts were right: Mr. Homberger is a thief and was responsible for stealing the uncommon prayer-books, having recognized their great value and tricked the woman who looks after the chapel. And Homberger isn’t his real name: he is in fact called Poschwitz. But he doesn’t profit from his crime. The same supernatural force that opened the books every year in the chapel is capable of much worse in Poschwitz’s London office, as the police find when they are called in after a sudden tragedy. Poschwitz has dropped dead in his office in the very act of opening the safe in which he was storing the stolen prayer-books. And although he was alone at the time, the death was certainly not natural or self-inflicted:

“Well,” said one of the inspectors, when they were left alone; and “Well?” said the other inspector; and, after a pause, “What’s the surgeon’s report again? You’ve got it there. Yes. Effect on the blood like the worst kind of snake-bite; death almost instantaneous. I’m glad of that, for his sake; he was a nasty sight.”

Friend of Israel Oliver Cromwell (1599–1658)

The words “Jew” and “Jewish” are never used in “The Uncommon Prayer-Book,” but James is clearly writing about a crooked Jew suffering supernatural retribution for preying on a naïve gentile. However, more is going on in the story than might be immediately apparent. James is being even more anti-Semitic than some might suppose, because Oliver Cromwell is not in the story by accident. Following his victory in the English Civil War, Cromwell gave the Jews permission to return safely to Britain for the first time since their expulsion by Edward I in 1290. How could he bring about his revolution? Some say that he was financed by Jewish bankers in Amsterdam. It is even possible that the execution of Charles I was, in part, an act of Jewish revenge on the English royal family, like the execution of Czar Nicholas II, a notorious anti-Semite, and his family after the Bolshevik Revolution.

M.R. James appears to have disapproved of Cromwell’s action and of the renewed Jewish presence in Britain. “The Uncommon Prayer-Book” contains an anti-Semitic revenge-fantasy, lightly disguised but unmistakeable. Furthermore, the anti-Semitism is given a specifically Christian context. A dishonest Jew dies because he steals Christian prayer-books and the name “Davidson” suggests not merely wise King Solomon, the son of David, but Jesus Christ too, who is also “the son of David” (see Matthew 1:1).

Hugh’s Hate

Christianity and anti-Semitism are similarly mingled in Saki’s “The Unrest-Cure,” which was first collected in The Chronicles of Clovis in 1911. However, unlike M.R. James, Saki was not a practising Christian and was probably agnostic or atheist. He uses Christianity merely for black comedy in the story. It begins when Saki’s young hero Clovis Sangrail is aboard a train and overhears a middle-aged man called J.P. Huddle being advised to take “an Unrest-cure” to shake himself out of “overmuch repose and placidity.” Clovis is en route to stay with an “elderly relative at Slowborough” and decides to entertain himself by supplying the “Unrest-cure.”

Saki (Hector Hugh Munro) (1870–1916)

Having noted Huddle’s address from a luggage label, he sends him a fake telegram, warning of an imminent visit by the local bishop. He then appears at Huddle’s house in the guise of the bishop’s “confidential secretary.” Clovis is a “thunderbolt” in the placid domestic routine to which Huddle and his sister are accustomed. But that’s the point: Clovis is supplying their Unrest-cure. Wrapping himself in mystery, he soon tricks Huddle into believing that the bishop has arrived:

“He is in the library with Alberti.”

“But why wasn’t I told? I never knew he had come!” exclaimed Huddle.

“No one knows he is here,” said Clovis; “the quieter we can keep matters the better. And on no account disturb him in the library. Those are his orders.”

“But what is all this mystery about? And who is Alberti? And isn’t the Bishop going to have tea?”

“The Bishop is out for blood, not tea.”

“Blood!” gasped Huddle, who did not find that the thunderbolt improved on acquaintance.

“To-night is going to be a great night in the history of Christendom,” said Clovis. “We are going to massacre every Jew in the neighbourhood.”

“To massacre the Jews!” said Huddle indignantly. “Do you mean to tell me there’s a general rising against them?”

“No, it’s the Bishop’s own idea. He’s in there arranging all the details now.”

“But — the Bishop is such a tolerant, humane man.”

“That is precisely what will heighten the effect of his action. The sensation will be enormous.” (“The Unrest-Cure”)

A Blot on the Century

Clovis next tells the horrified Huddle that the massacre will be performed at the house itself, whose garden, he warns, is already full of hidden and heavily armed men. They’re not really there, of course, but real local Jews soon are, having been summoned by further telegrams from Clovis. Huddle bundles them upstairs, frantically trying to think of ways to save their lives. When he protests to Clovis that the proposed massacre will place “a blot on the Twentieth Century!”, Clovis calmly replies:

And your house will be the blotting-pad. Have you realized that half the papers of Europe and the United States will publish pictures of it? By the way, I’ve sent some photographs of you and your sister, that I found in the library, to the Matin [i.e, Morning, a French newspaper] and Die Woche [i.e., The Week, a German magazine]; I hope you don’t mind. Also a sketch of the staircase; most of the killing will probably be done on the staircase.

Having horrified Huddle and his sister, filled their house with puzzled Jews and set the scene for an appalling massacre, Clovis slips away from the house and is never seen again. He reflects that Huddle will probably not be “in the least grateful for the Unrest-cure.”

Jews’ Shoes

And many early readers were surely “not in the least grateful” for the story when it was published before World War I. They must have been shocked by Saki’s attempt to wring humour from murderous anti-Semitism. It’s even worse today, after World War II, for the story is now read in the long and horrible shadow of public perceptions of the Holocaust. Modern readers who find it funny are plainly in urgent need of psychiatric help.

Accordingly, I hope that the National Security Agency and its British collaborator GCHQ are monitoring the reactions of all gentiles who visit web-pages that host it. But what about the reactions of Jews themselves to stories like “The Unrest-Cure” and “The Uncommon Prayer-Book”? What should we gentiles feel when we place ourselves in Jews’ shoes? “Disturbed” is the simple answer. Saki and M.R. James are highly intelligent, highly educated and highly sophisticated writers, minor but brilliant jewels in the crown of English literature. Yet both could write with apparent approval of a highly obnoxious prejudice: anti-Semitism, the Longest Hatred.

A suburb of Jerusalem

Indeed, Saki sinned elsewhere, describing the British empire as a “suburb of Jerusalem” in “Reginald at the Theatre” and basing a cruel practical joke in “A Touch of Realism” on the medieval expulsion of Jews from Spain. Worse still, Saki was a homosexual and well aware of the savage laws against his own kind. If Jews cannot trust a writer from a fellow persecuted minority, which gentiles can they trust?

None at all, it appears. Jews should be suspicious of all goyim. As the former Labour Member of Parliament Eric Moonan says: “I must admit, like most Jews, I see dangers everywhere.” The Jewish view of history is simple: for millennia, blameless Jews have been persecuted, massacred and expelled by Christian and pagan gentiles who are driven by nothing but irrational prejudice and malice. How, then, should they react to these omnipresent dangers?

There seem to be two solutions: Jews should either remove themselves from gentile societies or seek to control those societies and weaken the forces that underlie anti-Semitism. However, these solutions are not mutually exclusive: at present, Jews not only have their own nation, Israel, but also wield enormous power and influence in gentile-majority nations like America, Britain and France.

Motive, Means and Malice

But are they indeed seeking to control Western nations for their own ends? Or is that a hateful conspiracy-theory? It might be, but that doesn’t mean it’s false. It would surely be highly remiss of Jews not to seek control for their own ends. After all, the clear lesson of Jewish history is that gentiles are untrustworthy, irrational and murderous. If the Jewish version of history is true, then M.R. James and Saki must have based their hateful stories on fantasies about Jews, not on actual Jewish behaviour. How would you feel if, as a Jew, you saw malign fantasists like those two being rewarded with fame and riches by other gentiles? Would you not feel the urgent need to protect yourself?

But it’s noticeable, as the late Joseph Sobran pointed out, that every time Jews have been expelled from a Christian nation, they have immediately set about getting back in. Edward I officially expelled Jews from England, but they returned in secret and worked to rescind the expulsion. Oliver Cromwell duly obliged and let them back in, having been helped by Jewish money to win the English Civil War. That Jewish help raises an important point. It’s not enough for Jews to have the motive to control gentiles: they must also have the means to do so. Their higher average intelligence and financial acumen supply those means. It follows by simple logic that Jews should use their intelligence and wealth to counter gentile malice. Ethnically homogeneous Christian nations, with long histories of irrational anti-Semitism, are highly dangerous places for Jews.

Anti-Semitism and Jewish behaviour

Jews will naturally conclude that such nations should be made less ethnically homogeneous and less Christian. Merely by sitting in an armchair and reading M.R. James and Saki, one can see a plain motive for Jews to control and subvert the gentile societies that surround them. The question is whether they actually do so.

That question remains even if we discard the assumption that anti-Semitism is wholly disconnected from Jewish behaviour. Did M.R. James and Saki, so intelligent and sophisticated in other ways, really surrender to irrational, baseless hate on this single topic? Have gentiles always been malicious bigots and Jews always been blameless victims? As a great admirer of both M.R. James and Saki, I suggest that the truth might be much less simple than that.

Comments are closed.