Becky Manning: “He just carried this tremendous guilt for everything, for our son doing drugs. Then he started getting depressed, and then my husband took his own life.”

Paul Solman: “How did he do it?”

Becky Manning: “He blew his head off. I came home to that.”

Paul Solman: “Best friend Marcy Conner’s husband also killed himself.”

Marcy Conner: “He developed alcoholism very young in life.”

Paul Solman: “An addiction he shared with lifelong friends.”

Marcy Conner: “One died with a heart attack, but drug use and alcohol use played all the way through his life. Another one died of cancer, drank up to the very end. And my husband actually had a G-tube in, a feeding tube in, and poured alcohol down his feeding tube until he died.”

Excerpted from a PBS interview conducted in Kentucky.

I was in high school the first time I used heroin. I had started with marijuana in the tenth grade, which, like it or not, is a gateway drug. Marijuana gave way to psilocybin mushrooms, and then to alcohol, and the deluge poured forth. Oxycodone, LSD, MDMA, DMT, Ketamine, and then opium and cocaine. It was as if I was ascending a ladder, and heroin was its apex. I snorted it, smoked it, and injected it into my veins. My friends were well on their way to full-blown addiction, along with me. I went to a top-three university, and fell in with a group of hardcore addicts, in a league of our own that was entirely separate from the ubiquitous casual substance abuse that pervades American colleges. My existence was a blur, a bottomless pit that I could never fill, no matter how hard I tried. And try I did, with Xanax and other benzodiazepines, GHB, methamphetamine, hydrocodone, codeine, oxymorphone, morphine, and a litany of synthetic hallucinogens and amphetamines so new that they only had chemical names. And, of course, more heroin. Fentanyl was certainly in the mix. I liked speedballs, and I loved heroin, but my favorite drug was always baby blue Roxicodone, or “Roxy,” pure 30-milligram oxycodone. I had dealers, but I rarely needed them; the United States Postal Service delivered my drugs straight to my door from dark web markets on Tor.

Near the start of my second year of college, one of my two closest friends died of an overdose, a mixture of opioids and benzodiazepines. He had suffered from worsening scoliosis, his back-pain part of the reason he had originally been attracted to opioids. We had purchased our needles and descended into addiction together. At least three other boys from our high school graduating class died of opioid overdoses that same year. Another friend blew his brains out. Two acquaintances in college hung themselves. Eventually, after suffering through heroin withdrawal, I stopped using drugs. I then ran into the open arms of what would become my longest-lived demon, alcohol, and slipped into full-blown alcoholism in no time. At its height, I was drinking more than a fifth of hard liquor every day. On one such day, I blacked out behind the wheel and ran off of the road, flipped two or three times into a ravine, and totaled my car, escaping — miraculously — unscathed. This went on for about three years. And then, concurrent with my racial awakening, I found God again, whose company I had fled in adolescence. With His grace, I overcame the yoke that had held me in bondage for so many years. I have been completely sober for almost two years now, and I will never look back. When I reflect upon what I did—and in what prodigious quantities, I realize how lucky I am to be alive, how lucky I am to have overcome what hundreds of thousands of other Whites have succumbed to, the abnegation, erasure, and stench of waking death perfumed in the cloak of warmth, euphoria, and belonging.

I came from a wealthy home, and had a wonderful childhood in a decently small White town in the South. My parents did everything that they could for me, yet none of that stopped me from straying into the darkness. Drug addiction and alcoholism are, consciously or not, slow-motion suicides. These slow suicides have wrought unfathomable devastation during the past twenty years, one of the most consequential attacks on the White race in our history. The twenty-first century opioid epidemic is an assault from which we may never recover. Its ramifications cannot be overstated, and will ripple for decades. There are many of us who, perhaps tainted by the cancer of libertarianism, see addiction as a moral failing, a weakness for which we have only ourselves to blame. For some people, myself included, this diagnosis is accurate. But that is not the story of the opioid epidemic, the White Plague, or, as some White Nationalists call it, the White Death. No, the birth of the White Plague was largely iatrogenic, meaning “brought forth from the healer,” as legally prescribed OxyContin gave way to an opioid sea, as waves of oxycodone, hydrocodone, heroin, and fentanyl crested and crashed ashore, consuming our nation in its wake.

The White Plague is the handiwork of an irredeemably evil pharmaceutical industry, aided by innumerable pharmacists and physicians who both wittingly and unwittingly served as its facilitators and footsoldiers. However, if we peek behind the curtains of the great monolith of Big Pharma, we find the true culprits, the names and faces of the demons who deliberately crafted, planned, and inseminated the White Plague — the New York Jews known as the Sackler family, the patriarch of which was the architect of Big Pharma itself. Just as the Great Recession of 2008 provided us with a glimpse of the Jewish corruption of the American financial system into a malevolent oligarchy of organized crime, the tale of the Sacklers’ rise to power, of the Jewish perversion of the pharmaceutical industry, provides us with an incredible glimpse into the Jewish coup of the twentieth century, into the Jewish corrosion of every single one of our institutions. The White Plague is emblematic of Jewish deception, greed, and hatred — not apathy, but hatred — for Whites. The White Plague is also, almost coequally with the Jewish promotion of sexual nihilism, a powerful, calculated instrument of White genocide and control. Yes, they want us high in artificial bliss, in a spray-painted heaven where we are ripe for the picking. How did this, the Jewish drugging of White America, happen? Thanks in large part to the work of Sam Quinones[i], Beth Macy[ii], Anne Case, Angus Deaton[iii], and, above all, Gerald Posner[iv], we now know.

The road to Hell was first laid in Germany in 1804, when Friedrich Sertürner first isolated the morphine alkaloid from the opium poppy, naming it Morpheus, named by Ovid as the god of dreams, son of Somnus, the god of sleep. In 1827, Heinrich Merck initiated commercial morphine production at his family’s Engel-Apotheke, or “Angel Pharmacy,” the pharmacy that would eventually become Merck. Morphine became a key product for Ernst Schering and Friedrich Bayer, as well as their eponymous companies. After the Mexican War, the German cousins Charles Pfizer and Charles Erhart launched Pfizer. During and after the War for Southern Independence, morphine demand burgeoned, spawning the companies now known as Bristol-Myers Squibb, Wyeth, Parke-Davis, Eli Lilly and Company, and Burroughs Wellcome. During the War, over ten million opium pills and three million ounces of opium tinctures and powders were doled out to Union soldiers. After the War, the hypodermic needle, which had only recently been invented, was widely used to facilitate opium-based pain relief. Intravenous injection was thought to reduce addictive potential by bypassing the digestive system. At least one hundred thousand veterans became addicted.

In 1874, C.R. Wright synthesized diacetylmorphine for the first time, and in 1898 the opioid was independently rediscovered by Felix Hoffmann, a Bayer chemist. Bayer brought it to market under the name heroisch, or, “heroic.” By this time, opium and morphine were ubiquitous across America, used even by children. Postwar addiction was especially common among White Southerners, whose entire world had been put to the sword and then to the torch, whose tear-dimmed eyes struggled to see through a vortex of ash. With Bayer’s introduction of heroin, which it sold as a nonaddictive morphine substitute, opioid demand surged. Many a mother gave her children heroin for a good night’s rest. In 1914, in response to skyrocketing opiate demand due in part to morphine overproduction in the First World War, the United States Congress enacted its first effort at drug enforcement with the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act. The Harrison Act prohibited most cocaine use and most opiate importation, with one gaping exception: major manufacturers, such as Bayer, were exempt. In 1916, Martin Freund and the Jew Edmund Speyer first synthesized oxycodone, and in 1920 another pair of German scientists synthesized hydrocodone. For the next few decades, drug addiction remained a minor subculture, and it appeared that crisis had been avoided.

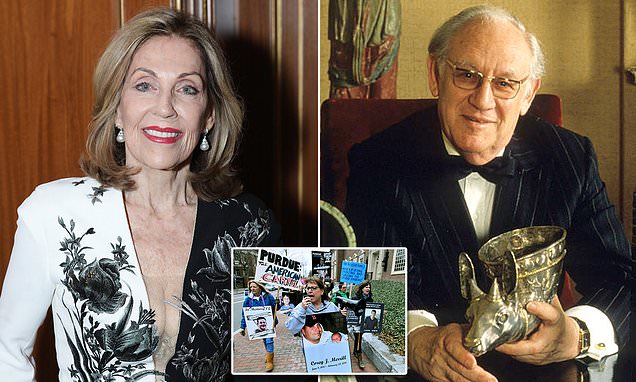

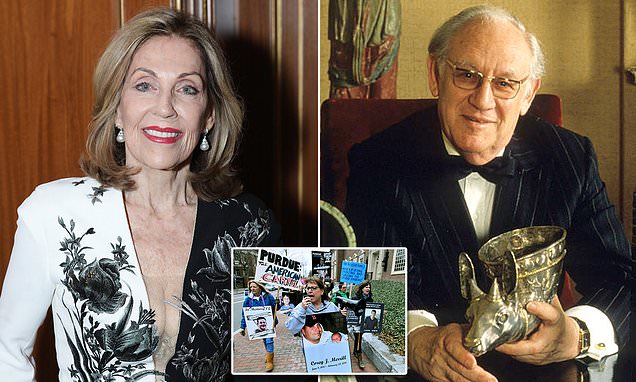

Arthur Sackler and his widow

In the early 1950s, Pfizer President John McKeen sought to develop an unorthodox, unprecedented marketing campaign to aggressively sell its new antibiotic, Terramycin. McKeen hired a young advertising executive and physician, a pioneer who was acknowledged by colleagues to be at the vanguard of the medical advertising industry, then in its nascency. His name was Arthur Sackler. Sackler, a self-described “Jewish kid from Brooklyn,” was born there in 1913 to Eastern European Orthodox Jewish immigrants, part of the deluge of two million Jews who swarmed into our nation from the Russian and Austro-Hungarian Empires from the 1880s to the 1920s. His parents named him Abraham, after his grandfather, but he preferred “the less Jewish-sounding” Arthur. Arthur had two brothers, Mortimer and Raymond, and, like his parents, he was a committed Marxist. Leftism predominated in his Jewish neighborhood, indeed in all Jewish neighborhoods, and the Sacklers resented “unrestrained capitalism” for the Great Depression which cost them their small grocery. New York Jews were the driving force behind the trade unions of the day, and the Sacklers subscribed to Forverts, or, “Forward,” a socialist daily that was also the world’s largest Yiddish newspaper. Jews accounted for at least forty percent of New York’s Socialist Party, and sixty percent of New York’s Jews had voted for socialist presidential candidate Eugene Debs.

In his last year of medical school, Arthur met a young Danish girl, the first of his three wives. His mother, “crushed” that her firstborn son would marry a despised Gentile, forced the girl to convert to Judaism. Arthur fundraised for Norman Bethune, a Canadian physician and Communist who volunteered as a battlefield surgeon for the Rojos in the Spanish Civil War before joining the Chinese Communists’ Eighth Route Army during the Second Sino-Japanese War, where he was commissioned by Mao Zedong himself to lead a mobile operating unit at the front. Later in life, when Arthur attended medical conferences in China, he told his hosts that nothing would be a greater honor to him than to be “a present-day Bethune.” The young Sackler also engaged in activism against blood bank segregation; it was of enormous importance to him that White and Black blood mixed. During the Second World War, Sackler got his first advertising post, working at Schering. The FBI, concerned about possible ties between the German-led Schering and the Third Reich, had six confidential informants placed within the company. Over the course of one year, one informant reported the emergence of “a Jewish influence,” and that the CEO, Julius Weltzien (whose mother was in fact Jewish), along with the other German emigrant executives, were “international Jews who would pour oil on both fires if a profit was in sight.”

To avoid the possible seizure of Schering, Sackler arranged for Alfred Stern, the American heir to a banking fortune, to purchase the company. Stern had been married to one of the daughters of Julius Rosenwald, part owner of Sears and Roebuck, and managed the family’s charitable foundation. Stern was enraptured by Freudian psychoanalysis, and funded the Institute for Psychoanalysis in Chicago. He remarried Martha Dodd, a Soviet asset who had been turned while in Berlin with her father, the then-American Ambassador to Germany, and Dodd recruited Stern in turn. Stern went on to become a director of the Leftist-controlled New York Citizens Housing and Planning Council. Stern and Dodd would later be outed and fled the nation, never again to return. In any case, Sackler was too late, and Schering was seized. Around this time, the philandering Arthur married his second wife, a Jewess named Beverly. They officially joined the Communist Party, the majority of whose membership was Jewish. The FBI file on Arthur and Beverly remained active from 1944 to at least 1968, and is thus far only partially declassified, with at least one file having been “routinely” destroyed.

The brothers Sackler worked at Creedmoor Psychiatric Hospital in Queens for a time, psychiatry and psychology being a perfect fit for Leftist Jews. From Schering, Arthur became Vice President of William Douglas McAdams, overseeing the then-fledgling medical advertising division, and soon became a one-third shareholder in the agency. Sackler detested the WASPs of Madison Avenue, later recalling, “You would sit at meetings where they would tell Jewish jokes, anti-Jewish jokes, and you had to sit there and swallow it, and laugh along with the boys.” The Jew would get the last laugh two generations later, taking his bloody vengeance upon the children and grandchildren of those patrician Whites whom he so hated. Arthur became fast friends with Ludwig Fröhlich, a Jewish sodomite emigrant from Germany. Both men actively concealed their Jewish identity. Fröhlich’s sister, Ingrid, obtained an influential position in high society through her brother’s connections, as a couture model for Sophie Gimbel, the American designer who ran Saks Fifth Avenue’s Salon Moderne custom dress shop. Ingrid was the favorite model of Wallis Simpson, the American divorcée for whom King Edward VIII abdicated the throne and thereby cleared the way for the Second World War. Ingrid, who hid her Jewish identity as painstakingly as her brother, was often heard to say, “Those Jewish people, I can’t stand them.”

The brothers Sackler incorporated their first of many joint businesses, Pharmaceutical Research Associates, and, setting the template for their future ventures, kept their ownership secret. Arthur, already a success, created the Arthur M. Sackler Foundation to shelter his art collection and make bequests; his brothers soon took the same course, and eventually all three set up parallel foundations and trusts in the United Kingdom. There are at least twelve Sackler foundations in New York alone. Arthur singlehandedly made McAdams the dominant medical advertising firm, its only comparable “competitor” an agency led by his dear friend Fröhlich, with whom Sackler regularly colluded. Unbeknownst to anyone else at the time, Sackler owned a controlling interest in that agency as well. At McAdams, Sackler pioneered direct drug sales to physicians; at the time, the FDA banned direct-to-consumer drug advertising. Arthur believed that “a drug company had to win the doctor’s loyalty for its entire product line,” and innovated several tactics that have since become standard practice, including promotional drug conferences, advertisements in medical journals, exhibits at medical conventions, and the saturation of physicians with free pharmaceutical samples. To bypass the aforementioned FDA ban, Sackler disguised product promotion as “news” in the consumer press, to induce patients to ask their physicians for the new drugs by name.

In 1948, Arthur approached Alfred Stern with another business proposition — he had set his sights on Purdue Frederick, a small patent pharmaceutical firm, and asked Stern to help him purchase it. By this time, the two had become good friends, with Arthur a regular visitor to his summer home, the same summer home that hosted meetings between Stern’s Soviet handlers and their other intelligence assets in the area. Stern nevertheless declined, and Arthur moved on for the time being. The next year, Sackler created the Medical and Pharmaceutical Information Bureau, or MPIB, the first company to specialize in seeding promotional articles, ostensibly about “new developments in medicine,” in the nonmedical press, part of his strategy to hype new, as yet unapproved drugs. Sackler practiced rampant insider trading, and concealed his ownership of MPIB, along with his large ownership stake in Pfizer. All the while, Sackler’s résumé expanded, and success gave way to success. In 1950, Arthur was appointed to chair the First International Congress of Psychiatry, he and his brothers having established themselves in biological psychiatry. Arthur, ever the greedy status-seeking Jew, missed the birth of his first son to deliver a speech. Money always came first. He became obsessed with collecting art, with the crates piling up in warehouses, unexamined; as his second wife would attest, most of the pieces were “known only by a packing list.” She would later write that Arthur “envisioned himself as the sun in his own solar system,” held in thralldom by a compulsive “necessity for prestige and recognition,” a deep “need to achieve…that his name not be forgotten by the world.”

In 1951, as aforementioned, Sackler singlehandedly plotted Pfizer’s Terramycin blitzkrieg, an unprecedently aggressive marketing campaign that directly gave birth to the legions of drug sales representatives that inundate physicians today. Arthur pioneered several mass pharmaceutical marketing strategies, including taking the campaign directly to physicians and blanketing medical journals, which were exempt from governmental oversight thanks to an FTC loophole that overlooked all advertisements directed at physicians, who were presumed to be capable of (and willing to) see deception; in doing so, Sackler transformed Pfizer into the powerhouse that it is today. The next year, Sackler helped Pfizer lead the other major pharmaceutical companies to lobby for a modification to American patent law, obtaining a lower innovation threshold and thus opening the floodgates for increased drugs on ever-shorter pipelines from development to market. Incidentally, this is the same year in which Pfizer lit the spark for the infernal Hell of factory farming, as well as antibiotic-resistant pathogens. Pfizer tested antibiotics on pigs and in short order began marketing them to farmers across the nation to accelerate the growth of their cattle, chickens, and pigs.

1952 proved to be an even more momentous year for Arthur Sackler. He finally bought Purdue Frederick Company, giving his brothers Mortimer and Raymond coequal shares. As per usual, none of the Sacklers’ names appeared on Purdue’s incorporation papers. At around this time, Arthur became acquainted with Félix Martí-Ibáñez, a Spanish psychiatrist and Marxist who worked for the pre-Franco Second Republic and represented it at the 1938 Universal Peace Congress. The Spaniard had also served in the Rojos medical corps. Together, Sackler and Martí-Ibáñez secretly formed a shell company, MD Publications, Inc. The two conspirators learned that the Washington Institute of Medicine, the publisher of the Journal of Antibiotics, was near bankruptcy; that publication’s editor was none other than Henry Welch, the head of the FDA Antibiotics Division. Welch’s superiors had no problem with his moonlighting position because Welch only received a small honorarium for the work. Sackler stepped in, agreeing to pay all of its debts, while MD Publications assumed control. Welch would receive 7.5 percent of all advertising income and 50 percent of net income from reprints sold to pharmaceutical companies; Sackler also agreed to publish Welch’s forthcoming book. Welch, for his part, disclosed none of this to the FDA, and his superiors went on believing that he was only receiving a trivial honorarium; Martí-Ibáñez assured him that no one would ever know the truth. Through MD Publications and a handful of other ventures, Arthur Sackler now personally controlled multiple medical journals, all of which were promptly packed to the gills with pharmaceutical advertisements.

Sackler operated an indescribably labyrinthine corporate shell game, creating new companies left and right, by which he concealed the fact that he and his brothers had a controlling interest in an inexorably expanding empire. At Arthur’s direction, Martí-Ibáñez and Welch established annual antibiotics conference, which Welch actually convinced the FDA to co-sponsor. At the inaugural conference, lavish receptions featured a tribute from President Eisenhower, and Welch and Martí-Ibáñez skewed the presentations to feature papers that favorably reviewed drugs from the biggest pharmaceutical firms, resulting in increased reprint sales, promoted as direct mail advertisements to physicians. The proceedings were printed, bound, and sold as a standalone book, while simultaneously the MD Encyclopedia was launched, a promotional tool disguised as a medical reference book. Meanwhile, the indefatigable Sackler patriarch used his old friend Fröhlich as the front man to incorporate what became International Marketing Service, or IMS, a data collection firm that paid physicians for their prescribing data.

Through IMS, Fröhlich fed Sackler prescribing data, which Sackler used to target sales at doctors who were large prescribers and most likely to be early adopters of new drugs. Simultaneously, Martí-Ibáñez published “scholarly” articles in Medical Encyclopedia to promote the same drugs, while Welch endorsed said drugs at the annual antibiotics conference in his official role, carrying the great weight of authority. By 1955, Sackler controlled over a dozen medical journals and marketing firms to seed promotional advertisements that appeared to be objective, his role totally hidden. Many of these advertisements reproduced the endorsements of “doctors,” complete with addresses, phone numbers, and office hours, all of which turned out to be, along with the “doctors,” nonexistent. Sackler’s chicanery did not stop here; indeed, he likely doctored the trial results of a Sackler product, L-Glutavite, and sold the one-product company for millions of dollars to a subsidiary of another company that was itself partially owned by the Sacklers.

Arthur maintained his Leftist affiliations, using his companies to hire dozens of blacklisted Communists and provide them a living until they could rejoin their respective fields. This, together with the extremely opaque corporate structures and funding sources for the Sackler empire, attracted the gaze of the FBI. Though federal agents were disconcerted by the fact that the Sackler businesses shared overlapping addresses and phone numbers, they were overwhelmed with other Soviet infiltration cases that they felt to be more pressing, and an official investigation was never undertaken. The FBI thus remained ignorant to the fact that, no matter who was listed on the incorporation papers, Arthur Sackler was the ventriloquist at the helm of it all. In 1959, Tennessee Senator Estes Kefauver took up the torch, spearheading a damning series of Senate hearings on the pharmaceutical industry that few paid any attention to. Kefauver’s investigative team was led by FTC veterans John Blair and Paul Dixon. Blair and Dixon, who uncovered evidence that the Sacklers were inordinately large shareholders in Pfizer and a number of other large pharmaceutical firms, wrote a 1960 memo with the subject: “Sackler Brothers.”

The investigators wrote, “During the course of the drug investigation, I have from time to time heard the rumors of the ‘Sackler Brothers’ or ‘Sackler Empire.’ … Any outfit which has been able to establish such close ties with the most powerful man in government with respect to antibiotics is hardly a fringe operation. … The clandestine manner in which they carry on their multitudinous activities also suggests there may be more here than meets the eye. Finally, the very number of organizations in every facet of the drug industry which are under their ownership, control, or influence, is such that they must be regarded as constituting a … large-scale operation.” Blair and Dixon concluded that “the Sackler empire is a completely integrated operation,” including creating “new drugs in its drug development enterprise,” ensuring that “hospitals with which they have connections” do the clinical trials and produce “favorable reports,” preparing advertising copy for publication in “their own medical journals,” and seeding articles in popular newspapers and magazines through “their public relations organizations.” For some reason that might not be so unfathomable, the Sacklers escaped unscathed and avoided public mention entirely. Henry Welch had no such luck; the millions of dollars that he had ferreted away were discovered and publicized, in response to which he had a heart attack and resigned from the FDA. Meanwhile, the Sackler empire continued its march; Arthur established the Medical Tribune and invited pioneer venture capitalist Georges Doriot to invest, marketing it as “the first independent paper for doctors,” again with the Sackler name concealed.

In 1957, under the aegis of Hoffmann-La Roche, Leo Sternbach (also Jewish) first synthesized benzodiazepines. Roche tapped Arthur to handle the saturation marketing campaign for Sternbach’s first creation, Librium. Fortuitously for Roche, Librium was granted FDA approval in 1960, perfectly coinciding with the creation of the Hamilton Anxiety and Depression Rating Scales by Max Hamilton (changed from Himmelschein). His Anxiety Rating Scale consisted of a fourteen-question survey, which laid the groundwork for the medicalization of anxiety as a psychiatric disorder. Roche distributed the Hamilton tests to tens of thousands of physicians, calculating that doctors would prescribe more Librium “if they felt they had a scientific basis for doing so.” As we will see, the Sacklers’ launch of OxyContin 34 years later would uncannily mirror the synergistic kismet under which Librium had been rolled out, with a reevaluation of “pain management” that included a ten-point “pain scale” by which physicians could supposedly “measure” patient pain. In order to bypass the FDA ban on direct-to-consumer drug advertising, Arthur created a promotional press release disguised as “news” about “advances in health,” containing grandiose claims about “taming” psychopathic prison inmates and aggressive zoo animals, dutifully repeated by magazines like Time, Life, Newsweek, National Geographic, and Esquire. Sackler presumed, correctly, that these magazines would make their way into patient waiting rooms across the United States. In less than three months, Arthur Sackler made Librium the best-selling tranquilizer in America.

In 1962, Arthur was questioned by the FBI over his ties to the since-departed Alfred Stern and Martha Dodd. He escaped unscathed by brazenly lying about his relationship with the Soviet agents. Called before Senator Kefauver’s subcommittee on another matter, Sackler perjured himself; with vile condescension, he exercised his skills as a master of obfuscation. If he could not deflect a question, he stonewalled or became combative, yet remained unfazed. In response to the horrific birth defects caused by thalidomide, Congress enacted the Kefauver Harris Amendment, tightening (though not by much) FDA oversight regarding drug efficacy and advertising claims. No matter; in 1963, Roche obtained FDA approval for Valium, another of Sternbach’s benzodiazepines, synthesized in 1959 to be the successor for Roche’s own Librium. As with that predecessor, Roche hired Arthur to wage his most aggressive blitz yet. Sackler’s favorite slogan: “No serious side effects.” In classic Sackler fashion, Arthur led Roche to finance the Network for Continuing Medical Education; by then, he had already started his own CME courses. Using prescription data collected by himself and Fröhlich’s IMS, Sackler personalized his Valium promotion and made the drug a tremendous hit—the best-selling drug on earth, the first hundred-million-dollar drug, making Roche the most expensive publicly-traded stock of its time.

As Valium took root, President Kennedy’s Advisory Commission on Narcotic and Drug Abuse released its final report, classifying Librium, the third best-selling drug in America, as addictive and dangerous. Roche, however, had nothing to fear; when the President’s face was blown apart, it took news of the report with it. The brothers Sackler, who, it will be remembered, were psychiatrists of the Freudian persuasion, specifically targeted Valium at women. In this effort, Arthur very likely authored Aspects of Anxiety, an attractive hardcover book released by Roche in 1965 and sent to the top ten thousand prescribing physicians in the nation. He had convinced Charles Branch, the President of the American Psychiatric Association, to write the preface. As with so many other Sackler efforts, the “informational tool” was just a marketing scheme in disguise, a method by which to bypass the FDA and FTC. Arthur also began sheltering of pharmaceutical intellectual property in overseas tax havens, utilizing a Swiss company that the Sacklers had incorporated in 1957. This innovation would later allow the family to evade hundreds of millions of dollars in taxes on their crown jewel, OxyContin.

In England, an early euthanasia advocate named Cicely Saunders took the first major incremental step toward the White Plague. Saunders almost singlehandedly introduced the “death with dignity” concept, experimenting with heavy opioid doses as a volunteer at St. Joseph’s. In 1967, she became the inaugural medical director at St. Christopher’s, the world’s first modern hospice, where she launched her quest to find a better painkiller than heroin, to revolutionize “pain management.” The Sacklers had purchased H.R. Napp Pharmaceuticals and Bard Pharmaceuticals the year before; when they became aware of Saunders’ quest, they promised her that they could deliver the magic bullet that she sought—thirty years later, the Sacklers would fulfill that dream and extinguish hundreds of thousands of others. Back in the United States, the Nixon Administration came to power on a promise of law and order, partially in response to the spiraling drug counterculture, including rampant heroin addiction among returning Vietnam veterans. Under the tenure of James Goddard, the FDA was more proactive than ever before, placing a ban on directly mailing free, unsolicited drug samples. Of course, there were still no limits to the quantity of pharmaceuticals that sales representatives could dole out, and drug firms responded in kind by adopting a vast array of perks for prescribing physicians, including all-expense-paid vacations, golf tournaments, and extravagant parties.

Arthur, ever the criminal mastermind, developed an ingenious marketing ploy for Purdue Frederick’s new disinfectant, Betadine. In 1968, Sackler had finagled himself a contract to supply the product in bulk to American soldiers in Vietnam. From there, he managed to sell it to NASA; when the Apollo 11 crew returned to earth, the very first action taken by the astronauts was to spray down their suits, module, and raft with Betadine. Arthur ran with it, placing full-page advertisements in all of the leading medical journals, with the headline: “Apollo 11 Splashdown! NASA Selects Betadine Antiseptic to Help Guard Against Possible Moon Germ Contamination.” Needless to say, Betadine boomed. So too did Arthur’s career; he was appointed to chair the International Task Force on World Health Manpower for the World Health Organization, delivered a report before the United Nations, and received lucrative grants from the Environmental Protection Agency. What did Sackler do with these taxpayer dollars? Primarily, he performed nihilistically cruel and utterly pointless experiments on defenseless animals, such as one in which he strapped rats into a tiny cage, attached them to a motorized shaker, and shook them violently from side to side 150 times per minute for half an hour while simultaneously bombarding them with recordings of New York subway trains. After four months of torture, the last of the rats died. And what grand conclusions did this indescribable suffering make possible? That stress can kill.

The Sackler empire continued to metastasize, unopposed. In 1969, the Sacklers placed their Swiss corporation on a project to develop a timed-release coating, filing an obscure patent in 1971. The next year, the Sackler-owned Napp Pharmaceuticals and Bard Laboratories developed the first working compounds that they believed might be adaptable as a controlled-release formulation for oral medications. In 1980, the project culminated with MST Continus, the first drug to feature a timed-release coating, releasing morphine steadily over twelve hours. This was an essential selling-point, for most doctors erroneously believed that timed-release narcotics would be “addiction-proof.” Here was the revolutionary painkiller that Cicely Saunders had dreamed of. Here was the technology that, sixteen years later, would unleash pestilence upon our people. By this time, Arthur’s network of medical publications reached over one million doctors internationally; one of his magazines was Sexual Medicine Today, targeted toward psychiatrists; articles included: “Nazi Sexual Practices”; “Do Sore Nipples Inhibit Sexual Foreplay?”; “Medical Story of the Castrati”; “Homosexual Prostitute: A Boy Prostitute”; “Aphrodisiacs and Drugs”; “Sex Change Surgery”; and, “Quest for the Ultimate Orgasm.”

As aforementioned, Sackler was pathologically obsessed with status and prestige. He bitterly resented the patrician WASP establishment of New York, the members of which saw him for the nouveau riche wannabe that he was. Arthur had developed a close friendship with another up-and-coming Jew, a young Department of Justice lawyer named Michael Sonnenreich. Sonnenreich went on to formulate the Controlled Substances Act, and eventually switched teams, joining Sackler’s legal army. His mother was an executive administrator at Manhattan’s Temple Israel, while his father was the membership director of B’nai B’rith; it was his connection with Sackler, though, that reaped him his fortune, and Sonnenreich is now an art collector and “philanthropist.” Sackler minimized his Jewish identity until he got a revealing “pep talk” from Sonnenreich: “Let me explain something to you, Arthur. If there is a pogrom, I don’t care what you tell them you are, you are going to be in the same cattle car as I am. Stop the games. … They are not going to work. You could marry all the Christian girls you want, it ain’t going to work. They are still going to put you on the train and that’s that.”

The ascendant Jew made his mark upon American high society, displacing the old WASP order just as the Jewish coup was enshrined within every single institution within our nation. Sackler, after creating a company expressly to bequeath 39 percent of its shares to Columbia University, was appointed to Columbia’s Advisory Council of the Department of Art, History, and Archaeology. The fabled Metropolitan Museum of Art, struggling with fundraising, allowed Arthur to step in and raise his profile further, donating inflated shares of Sackler-controlled companies and hundreds of thousands of dollars to gain a Sackler gallery and a highly irregular storeroom inside the museum to house his private collection. Later, Sackler bankrolled the Met’s new Egyptian Temple of Dendur, along with galleries for Assyrian and Egyptian art, an archaeological laboratory, and a newly-named Sackler Wing. The Met also agreed to add all Sackler donations to its permanent collection. Arthur Rosenblatt, the Jewish second-in-command at the Met, had no issue with taking Sackler’s money, stating that the Met needed “every rich Jewish real estate mogul” because they had “run out of WASPs with money.” When news of Sackler’s specially arranged personal storage room in the basement of the Met hit the press, a reporter called for comment, to which the Met’s General Counsel said that anything that happened at the Met was “none of the public’s damned business,” despite the fact that the Met was publicly funded. The New York Attorney General opened an investigation into why the museum had to date spent nearly one million dollars on storing Sackler’s personal collection.

After Arthur married his third wife, he purchased a 27-room triplex at 666 Park Avenue, his occupancy a sick mockery of a residence that had originally been commissioned by the Vanderbilt family in 1927. Amidst growing tensions between Sackler and the Met, Arthur agreed to donate four million dollars and one thousand pieces valued at fifty million dollars to the Freer Gallery, part of the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C. In return, the Smithsonian established the Arthur M. Sackler Gallery directly on the National Mall, the first modern structure on the Mall to be named for a private individual. Arthur underwrote construction of the Sackler School of Medicine in Tel Aviv, which, as of 2018, is Israel’s largest medical research facility. Along with the Arthur M. Sackler Museum at Harvard University, we have , among others, the Sackler Gallery for Chinese Art at Princeton, a research lab at Long Island University, the Arthur M. Sackler Sciences Center at Clark University, the Sackler Institute of Graduate Biomedical Science at New York University, the Arthur M. Sackler Institute at Tufts University, a Sackler Wing at the Louvre, the Sackler Center for Arts Education at the Guggenheim Museum, and the Sackler Institute for Comparative Genomics at the American Museum of Natural History. Sackler also donated to the National Academy of Sciences. As Arthur’s second wife said, Sackler “found safety and comfort in objects. … The irony, of course, was they made him their slave.”

Sackler had made Valium ubiquitous, his greatest success yet, with an estimated twenty percent of American women using regularly. It became the first ever billion-dollar drug, despite increasing reports of addiction, which, of course, Roche denied was possible. The DOJ upgraded both Librium and Valium to Schedule IV, slowing the juggernaut, although Valium still remained the top drug in America. In 1964, Roche had patented Klonopin, another of Leo Sternbach’s benzodiazepines; in 1977, Sackler was chosen to handle its national rollout. A Roche competitor, Upjohn Laboratories, was about to blow them out of the water with its new benzodiazepine, patented in 1971 and approved in 1981. Xanax was an instant hit, thanks in no small part to the addition of “panic disorder” to the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. By using a DSM anxiety diagnosis and getting FDA approval for a biological solution on which it had a patent, Upjohn set a new template that would be seized upon by many a pharmaceutical firm since, as the DSM has inexorably enlarged the number of recognized “mental illnesses.” Gilbert Cant wrote a famous piece for the New York Times Magazine, “Valiumania,” which Arthur took care to clip and save. Sackler underlined its last two sentences: “A drug has no moral or immoral qualities. These are the monopoly of the user or abuser.”

As aforementioned, the 1980 release of MST Continus by the Sacklers’ Napp Pharmaceuticals was heralded as the first extended-relief oral narcotic painkiller. Physicians were unconcerned about the fine-print warning that the tablets must be swallowed and not chewed, blissfully ignorant or dismissive of the fact that if the tablets were chewed, the entire dose of morphine, up to one hundred milligrams per pill, would be released. By some strange coincidence, the true story of which will likely never be known, the Sacklers benefited from a concurrent reevaluation of opioid prescription, itself part of a revolutionary “pain management” movement. Chronic pain was a massive medical problem that had been found intractable by the major pharmaceutical companies; morphine, oxycodone, hydrocodone, and other opiates were effective, but were all designated controlled substances because of their extremely high addiction potential. A small vanguard of physicians set out to change that, positing that opioids were unfairly maligned and that as such, they should be dispensed far more freely. Until this time, there was no “pain management” industry; American physicians generally considered pain to be a symptom of some underlying condition, not an independent issue. John Bonica, a former professional wrestler, carnival strongman, and light heavyweight world boxing champion turned anesthesiologist, became the “founding father of pain relief,” publishing a massive monograph in 1953 and cofounding in 1974 the International Association for the Study of Pain, whose Pain journal is the field’s leading publication. In 1977, a team of physicians and researchers used Bonica’s research to launch the American Pain Society.

1980 marked a watershed with the publication of a 99-word letter to the editor, only five sentences long, published in the New England Journal of Medicine and authored by Hershel Jick, a leading physician at a drug surveillance program partially funded by the National Institutes of Health and the FDA, along with his graduate student, Jane Porter. Jick and Porter summarized their examination of Boston University Hospital patient records, finding in over ten thousand patients only “four cases of reasonably well-documented addiction in patients who had no history of addiction.” From that cursory research, the duo extrapolated the bizarre, wild, and inexplicable conclusion that went on to upend the world: “Despite widespread use of narcotic drugs in hospitals, the development of addiction is rare.” Their letter cited two prior drug surveillance studies; both involved only hospitalized patients who were given small doses of opioids in that controlled setting, with only a handful taking opioids for more than five days. Furthermore, not one of them was given painkillers after his discharge from the hospital.

The letter drew such attention precisely because it had been published in the prestigious New England Journal of Medicine. Very few people knew that the journal almost never hired outside experts to review letters to the editor. As Gerald Posner notes, if Jick and Porter’s letter had been subjected to peer review, its conclusion would have been reformulated to instead read that “‘the development of addiction is rare’” in the controlled setting of a hospital.” Of course, that did not happen, and, over the next twenty years, that letter was cited more than six hundred times in textbooks, medical journals, and other publications to draw far broader conclusions regarding the safety of opioids. Scientific American called the letter “an extensive study” and rewrote its conclusion to say that “when patients take morphine to combat pain, it is rare to see addiction.” Time called it “a landmark study,” proving that the “fear” of addiction “is basically unwarranted.” The WHO cited the letter as a “cornerstone.” In 1986, Russell Portenoy and Kathleen Foley, respectively a physician and palliative care specialist, took things a step further. Portenoy and Foley published the results of a clinical study in Pain, involving 38 patients, concluding that opioids were “a safe, salutary, and more humane alternative to the options of surgery or no treatment in those patients with intractable non-malignant pain and no history of drug abuse.”

Portenoy and Foley’s paper was merely the first of dozens of such articles published in medical journals over the next few years; always predicated upon anecdotal reports or statistically insignificant trials, these articles softened the public image of opioids and buttressed the claim that they were extremely “effective in treating long-term chronic pain.” Buried in the footnotes, one could find that “long-term” usually only meant twelve to sixteen weeks, while “effective in treating” simply meant “superior to placebo.” Portenoy sacralized opioids as a “gift from nature” and lambasted doctors whose “opiophobia” prevented them from heavily prescribing them. Along with the American Pain Society, physicians formed the American Academy of Pain Medicine and the American Society of Addiction Medicine, and urged chronic pain patients to form special interest groups and petition Congress and the FDA to loosen dispensing restrictions. In 1990, Mitchell Max of the American Pain Society wrote a popular editorial in the Annals of Internal Medicine arguing that pain must be prioritized as a vital sign in a prominent position on patient charts, echoed more impactfully by another Pain Society doctor, James Campbell, who suggested “pain as the fifth vital sign.” Just as the Hamilton Rating Scales had provided “standardized diagnostic tests” for numerically quantifying anxiety and depression, several “pain assessment” tools came into use in the mid-1980s.

In 1989, J. David Haddox, an anesthesiologist and dentist who went on both to become President of the American Academy of Pain Medicine and work for Purdue Pharma, wrote in Pain about his theory of “pseudoaddiction.” According to Haddox, “pseudoaddiction” was a syndrome that caused “behavioral changes” that only looked like addiction, whereas, in reality, Haddox argued, it was caused when doctors did not prescribe enough opioids. Indeed, Haddox contended that it was “only evidence that the patient was desperate to get enough medication for pain relief,” and that the only solution was to dispense more narcotic painkillers. Cynically, the three leading pain associations embraced “pseudoaddiction,” hook, line, and sinker, and released a joint statement stating that it “can be distinguished from true addiction in that the behaviors resolve when pain is effectively treated.” Twenty-five years later, a comprehensive study would reveal that, of the 224 “scientific” articles in which “pseudoaddiction” was cited, only eighteen provided even skimpy anecdotal evidence. This study concluded that the term had “proliferated in the literature as a justification for opioid therapy for non-terminal pain.”

The same month that Haddox’s article was released, a dozen prominent physicians published the “Physician’s Responsibility Toward Hopelessly Ill Patients” in the New England Journal of Medicine. Although that statement only concerned the terminally ill, its conclusion became a rallying cry for the opioid reevaluation movement: “The proper dose of pain medication is the dose that is sufficient to relieve pain and suffering.” Portenoy et al thus contended that opioids should be a first treatment option, with no maximum dosage, positing that opioids must be dispensed until a patient’s pain has been “relieved.” A few years earlier, New Jersey had become the first State to pass “intractable pain treatment” law, stating that patients had a right to pain treatment and shielding physicians from criminal or civil liability if the prescribed narcotics resulted in addiction. Over the next couple of years, eighteen other States followed suit. It should by now be evident that the Sacklers could not have designed a better prelude to their OxyContin release, only a decade away, if they had planned everything themselves. By the time pain was on its way to becoming “the fifth vital sign,” however, OxyContin was barely past its embryonic stage.

For the next ten years, Purdue spent tens of millions of dollars subsidizing the very physicians, advocacy groups, and “pain societies” that worked tirelessly to liberalize opioid drugs. “Pioneers” like Portenoy and Haddox received lucrative speaking contracts, while Purdue poured money into medical schools, professional conferences, and continuing education courses. Many a retired FDA and DOJ official made their way through the revolving door to the Sackler feeding trough. Later, as cascading reports of opioid addiction, overdoses, crime, and pill mills began to blanket the nation, these early opioid advocates stuck to their original stories. One may only guess as to why; aside from malevolence toward rural and suburban working-class Whites, and aside from Big Pharma money, it would appear that egoism played a role. In other words, the most charitable explanation that we can supply is that these men simply did not wish to admit how brutally wrong they were, thus avoiding the acceptance of any responsibility for the millions of White lives their work brought to absolute ruin. As late as 2010, Russell Portenoy held the party line in a Good Morning America appearance, assuring the American public—and, more specifically, the suburban White mothers who make up that program’s audience—that “addiction, when treating pain, is distinctly uncommon. If a person does not have a history…of substance abuse, and does not have a very major psychiatric disorder, most doctors can feel very assured that that person is not going to become addicted.” And yet that same year, Portenoy had no qualms about confiding privately in another doctor that “I gave innumerable lectures in the late 1980s and ‘90s about addiction that weren’t true.”

Due to the slow FDA approval process for controlled substances, MST Continus was not given the green light for the American market until 1987, seven years after its release in the United Kingdom. For the United States, Arthur renamed the drug MS Contin. With only five years before generic manufacturers would be allowed to undercut them, Richard Sackler, Raymond’s son and thus Arthur’s nephew, spearheaded a project that he believed would protect Purdue’s profits for the long haul — a new, improved, controlled-release narcotic painkiller targeted not just at the terminally ill, but everyone. Robert Kaiko, Purdue Frederick’s Vice President of clinical research, enthusiastically agreed with Richard. The two men believed that the active ingredient of MS Contin, morphine, was problematic, as its reputation had grown too notorious, with a stigma even among physicians that it should primarily be used for end-of-life palliative care, rather than a product for “every application.” Eventually, they settled on oxycodone.

Though there were two other pharmaceutical companies developing extended-release narcotic painkillers, neither were utilizing oxycodone. Additionally, while there were oxycodone-based painkillers on the market, like Percodan (oxycodone-aspirin) and Percocet (oxycodone-acetaminophen), they were immediate-release pills. So, in classic Sackler style, Purdue’s extended-release oxycodone-only pill would be the first of its kind. Shortly before the OxyContin launch, as the Sacklers entertained the idea of concealing its abuse potential and selling it as an uncontrolled drug outside of the United States, Kaiko emailed Richard to express his concerns over the possibility of selling OxyContin uncontrolled. Kaiko wrote that, “if OxyContin is uncontrolled … it is highly likely that it will eventually be abused.” Richard Sackler’s response: “How substantially would it improve your sales?” As with all of the other Sackler ventures, the family used their impenetrable corporate shell game to assign the patents for each different part of the development process to different subsidiaries. Richard lobbied Arthur to create a new company, Purdue Pharma, as an independent corporation spun out of Purdue Frederick. For the time being, this went nowhere, as Arthur, the progenitor of Big Pharma, was preoccupied. In 1985, Arthur had joined the board of directors of Scientific American, and, the next year, Linus Pauling, the American biochemist and recipient of the Nobel Prize in Chemistry and the Nobel Peace Prize, dedicated his book to Sackler. Pauling shared Sackler’s fervor for Leftism. In 1987, Arthur gave the world his greatest gift—he died from a heart attack, thereby igniting decades of internecine legal battles between his relatives. The Sacklers, undaunted by the death of their patriarch, were only just getting started on consummating Arthur’s depraved legacy. Soon, they would release their White Plague.

Go to Part 2.

[i] Quinones, Sam. Dreamland: The True Tale of America’s Opiate Epidemic (Bloomsbury, 2015).

[ii] Macy, Beth. Dopesick: Dealers, Doctors, and the Drug Company that Addicted America (Little, Brown and Company, 2018).

[iii] Case, Anne, & Deaton, Angus. Deaths of Despair and the Future of Capitalism (Princeton University Press, 2020).

[iv] Posner, Gerald. Pharma: Greed, Lies, and the Poisoning of America (Avid Reader Press, 2020).

Of course, the Sacklers and their Purdue executives were not the only demons who facilitated the White Plague. We must not lose sight of the fact that the Jewish-dominated American healthcare system itself, by far the most expensive on earth, is not only failing to halt the precipitous fall of White life expectancy, but is actively fueling the conflagration. The Sacklers are indeed singularly responsible for the White Plague; without their deception, greed, and anti-White animus, it could not have occurred. However, while the Sacklers were certainly the heart (or rather, the gaping black hole where a heart should be) of the Hydra, the Beast had many heads. As Gerald Posner cautions, “By putting the responsibility for the crisis so squarely on Purdue and the Sacklers, there is a risk [that] others who played material roles in creating and feeding the epidemic may not pay a price. That is the hope among thousands of others, sales representatives and executives of rival pharma companies with their own opioid products, overprescribing doctors, FDA bureaucrats who did not want to restrict OxyContin, pharmacists who diverted prescriptions to the black market, and pain management experts who preached that opioids were not addictive when prescribed for pain.” In this respect, the Sacklers appear to be another sacrificial scapegoat for the Jewish ruling class; in other words, the Elders of Zion occasionally sacrifice one of their own for the good of the whole. For example, Bernie Madoff was sacrificed as the avatar for the entire Great Recession. “#MeToo” was created and Harvey Weinstein was sacrificed, in order to further conceal the pervasive pedophilia in Jewish Hollywood. Jeffrey Epstein was suicided, and, though it remains to be seen what will become of Ghislaine Maxwell, she certainly intended to be arrested and thus poses no threat to the System.

Of course, the Sacklers and their Purdue executives were not the only demons who facilitated the White Plague. We must not lose sight of the fact that the Jewish-dominated American healthcare system itself, by far the most expensive on earth, is not only failing to halt the precipitous fall of White life expectancy, but is actively fueling the conflagration. The Sacklers are indeed singularly responsible for the White Plague; without their deception, greed, and anti-White animus, it could not have occurred. However, while the Sacklers were certainly the heart (or rather, the gaping black hole where a heart should be) of the Hydra, the Beast had many heads. As Gerald Posner cautions, “By putting the responsibility for the crisis so squarely on Purdue and the Sacklers, there is a risk [that] others who played material roles in creating and feeding the epidemic may not pay a price. That is the hope among thousands of others, sales representatives and executives of rival pharma companies with their own opioid products, overprescribing doctors, FDA bureaucrats who did not want to restrict OxyContin, pharmacists who diverted prescriptions to the black market, and pain management experts who preached that opioids were not addictive when prescribed for pain.” In this respect, the Sacklers appear to be another sacrificial scapegoat for the Jewish ruling class; in other words, the Elders of Zion occasionally sacrifice one of their own for the good of the whole. For example, Bernie Madoff was sacrificed as the avatar for the entire Great Recession. “#MeToo” was created and Harvey Weinstein was sacrificed, in order to further conceal the pervasive pedophilia in Jewish Hollywood. Jeffrey Epstein was suicided, and, though it remains to be seen what will become of Ghislaine Maxwell, she certainly intended to be arrested and thus poses no threat to the System.