Triggered by Beethoven: The Cultural Politics of Racial Resentment

2020 was meant to be a year of celebration for Beethoven who was baptized 250 years ago (his exact date of birth is unknown) in Bonn on December 17, 1770. COVID-19 prompted the cancelation of commemorative concerts of Beethoven’s music, but the pandemic didn’t quell efforts by anti-White activists to attack the composer’s reputation and dominant place in the cultural pantheon of the West. Rather than a year full of performances of the great composer’s sonatas, string quartets, concertos and symphonies, 2020 saw repeated attacks on Beethoven for the crime of being a White male genius and for embodying the European musical tradition.

Beethoven is the most-performed composer in the repertoire, and his anniversary year was planned to be no exception. Before the widespread cancellation of concerts, 15 to 20 per cent of the repertoire programmed by leading orchestras was music by Beethoven. Widely regarded as the greatest composer of all time, Beethoven is inescapable because he remade almost every genre of concert music that matters. The concerto and symphony in his hands became driving musical narratives of heroic struggle. His late string quartets open a profound window on to the soul. Unlike his predecessors who were craftsmen who supplied a commodity to a paymaster, Beethoven ushered in the age of Romanticism by insisting on his creative independence and the absolute importance of self-expression: “What is in my heart must come out so I write it down.” This was manifested in his refusal to take a secure, salaried position like his one-time tutor Joseph Haydn who was the master of music for a feudal landowner in what is now Hungary.

Beethoven’s heroism in overcoming the worst thing that can happen to a composer — worsening deafness from young adulthood — to compose some of the greatest music ever has awed generations and become emblematic of triumph over adversity. All the stories of Beethoven’s misanthropy, his eccentricity and wildness, date from the decline in his hearing, which often caused him acute physical pain. Only his art prevented him from taking his own life: “It seemed to me impossible to leave the world until I had brought forth all that I felt was within me.” While Beethoven’s confidence as a pianist and conductor gradually diminished with his creeping deafness, his imaginative powers as a composer grew stronger and stronger, and he cast a daunting shadow over his successors: Brahms did not feel confident tackling a symphony until he was in his forties.

Beethoven excelled at his trade because he was born with a gift and worked at it as hard as it is possible to work. Swafford notes how his sketches and manuscripts reveal that:

Nothing came easily to him, least of all composing. Where Mozart could dream up a whole piece in his head while playing billiards, Beethoven had to worry and whip every note into place in his sketches. The sketchbooks are amazing documents: gold being refined from raw ore, pedestrian ideas becoming revolutionary concepts, incoherence being forged into clarity and purposefulness. Even the final manuscripts are a morass of scrawls and blots and revisions on top of revisions.[1]

Beethoven’s Faustian spirit made him into the kind of figure that dominated the imagination of nineteenth century Europeans: the superhuman genius, the revolutionary hero, the master of his own fate and transformer of the world. This reputation carried over into the twentieth century with the influential French writer Romain Rolland holding the composer up as a role model for a less heroic age, epitomizing personal sincerity and self-denial — in a word, authenticity.[2]

Attacks on Beethoven

Laudatory references to White male geniuses like Beethoven inevitably trigger rage from anti-White commentators who huff that it has “long been an argument of white supremacists, Nazis, Neo-Nazis, and racial separatists that ‘classical music,’ the music of ‘white people,’ is inherently more sophisticated, complicated, and valuable than the musical traditions of Africa, Asia, South America, or the Middle East, thus proving the innate superiority of the ‘white race.’” Seen through the Cultural Marxist lens of critical race and gender theory, Beethoven’s music dominates the concert repertoire not because of its exceptional quality, but because White-male privilege and assumptions about White-male genius keep it there. Linda Shaver-Gleason insisted Beethoven’s dominant place in the canon was the result of a White supremacist conspiracy which “intentionally suppressed” the music of non-White composers “in the service of a narrative of white — specifically German — cultural supremacy (because, alas, that too is part of Western culture).”

Slate online recently rebuked Beethoven for his mononym: the fact he is known by a single name, like Michelangelo or Shakespeare. This practice supposedly gives the pedestal of nomenclature to “straight white men at the expense of everyone else.” White male composers, it is claimed, “became so ensconced in elite musical society’s collective consciousness that only one word was need to evoke their awesome specter. Mouthfuls of full names became truncated to terse sets of universally recognized syllables: Mozart. Beethoven. Bach.” The works of composers with mononyms are therefore assumed to be “on a different plane,” whereas this assumption is, we are told, actually the product of “centuries of systematic prejudice, exclusion, sexism and racism.”

In a recent Vox podcast and article, musicologist Nate Sloan and songwriter Charlie Harding claim the opening bars of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (the famous da-da-da-DUM motif) should not be given their traditional interpretation — the sound of fate knocking on the door and Beethoven’s resilience in the face of encroaching deafness — but should be construed as the sound of the gate slamming shut on minorities, such as “women, LGBTQ+ people, people of color.” They assert (without evidence) that “wealthy white men” embraced the Fifth Symphony as a “symbol of their superiority and importance.” Black clarinetist Anthony McGill agrees, likening the inescapability of the Fifth Symphony to a “wall” between classical music and new, racially-diverse audiences.

Jewish music writer Norman Lebrecht defended Beethoven against Sloan and Harding’s polemic by citing Beethoven’s “liberal” credentials, claiming, for example, that they “fail to explore how Beethoven’s Fifth served for millions as a symbol of freedom in the war against Nazism.” Unmentioned by Lebrecht is the fact that, despite Beethoven’s politics — which were liberal for their time (he had republican sympathies) — the composer made repeated comments critical of Lebrecht’s own ethnic group. On one occasion, he rejected the idea of selling his Missa Solemnis to the Jewish music publisher Adolf Schlesinger in favor of the German publisher C.F. Peters, informing the latter that: “In no circumstances will Schlesinger ever get anything more from me, because he too has played me a Jewish trick.” Beethoven’s disgust with Schlesinger was prompted by repeated experiences of being short-changed with “such insulting niggardliness, the like of which I have never experienced.”[3] In a letter of 1823, Beethoven called Schlesinger “a beach peddler and rag-and-bone Jew.” In his negotiations with another publisher, Beethoven noted the publisher was “neither Jew nor Italian” and that as he himself was also neither of these, “perhaps we shall come to some agreement.”[4]

Sloan and Harding are on stronger ground in arguing the thematic complexity of the Fifth Symphony necessitated unprecedentedly close listening to fully grasp, and this, in turn, led to the establishment of new norms of concert behavior. These norms — sitting still, staying quiet and not clapping mid-piece — led to the strict culture of classical music that persists to this day, and which allegedly oppresses non-Whites who cannot reasonably be expected to conform to such standards of behavior. Sloan and Harding lament that classical concerts are the sole remaining American institution that typically insists on starting on time. Rather than a sign of respect for all parties involved, these behavioral and procedural norms are, they insist, symbols of White supremacy which alienate “diverse audiences,” and their origins can be traced to Beethoven.

Jewish music writer for The New Yorker, Alex Ross, labelled the planned 2020 Beethoven celebrations “a gratuitously excessive celebration of the two-hundred-and-fiftieth birthday of a composer who hardly needs any extra publicity.” He insists that, in the wake of the Black Lives Matter riots, an examination of the relationship between classical music, which he labels “blindingly white, both in its history and present,” and racism is “sorely needed” because of the genre’s “extreme dependence on a problematic past.” Ross claims that when the classical music tradition was transplanted to the United States, the “white majority tended to adopt European music as a badge of its supremacy. The classical-music institutions that emerged in the mid- and late nineteenth century — the New York Philharmonic, the Boston Symphony, the Metropolitan Opera, and the like — became temples to European gods. … Little effort was made to cultivate American composers; it seemed more important to manufacture a fantasy of Beethovenian grandeur.”

For Ross, classical music can only “overcome the shadows of its past” if it commits itself to a “much more radical confrontation with the white European inheritance,” and by programing more non-White composers like Julius Eastman — a Black composer whose “improvisatory structures, his subversive political themes, and his openness about his homosexuality give him a revolutionary aspect, yet he also had a nostalgic flair for the grand romantic manner.’”

In the frontline of attacks on Beethoven in 2020 was Black music writer and Hunter College academic Philip Ewell, who penned an article titled “Beethoven was an Above-Average Composer — Let’s Leave it at That.” Ewell begrudges the laudatory epithets routinely applied to White composers like Beethoven and their works. For Ewell, adjectives like “genius” and “masterwork,” evoke slavery (master-slave) and sexism (master-mistress), and the classical music lexicon is, in his assessment, overflowing with euphemisms that disguise and reinforce the “white-male frame.”

In addition to “master’ and its derivatives, here are some of the other common euphemisms for white and whiteness in music theory’s white racial frame: authentic, canonic, civilized, classic(s), conventional, core (“core” requirement), European, function (“functional” tonality), fundamental, genius, German (“German” language requirement), great (“great” works), maestro, opus (magnum “opus”), piano (“piano” proficiency, skills), seminal, sophisticated, titan(ic), towering, traditional, and western. Even terms such as “the long nineteenth century” and “fin de siècle” can be considered euphemisms for whiteness and white framing for their close associations with dates and events (and languages) significant to Europe and Europeanism. Such euphemisms are intended to sublimate whiteness into less objectionable forms, thus mitigating the effect of whiteness on music theory and hiding its existence.

Rather than enjoying a merited reputation for the brilliance and originality of his oeuvre, Ewell insists Beethoven’s fame has been upheld by such lexical scaffolding, claiming Beethoven, “along with countless other white males, has been propped up by the white-male frame, both consciously and subconsciously, with descriptors such as genius, master and masterwork.” In Ewell’s jaundiced assessment, Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony is “no more a masterpiece” than Esperanza Spalding’s 12 Little Spells (click the links and judge for yourself). The status of Beethoven’s Ninth is purely, he argues, a product of music theory’s “white-male frame” which “obfuscates race and gender.”

Ewell’s attack on Beethoven is an adjunct of this broader hostility to classical music’s “white racial frame” which, he insists, reinforces the hierarchy of White male composers, and “works in concert with patriarchal structures to advantage whiteness and maleness while disadvantaging POC and non-males.” This frame purportedly encompasses Western tonality itself (with its major-minor harmony and its equal-tempered scale) which is assumed to be the “master” language. Ewell even regards the Gregorian calendar as “white racial framing writ large,” insisting “no one can deny the racial element behind how the world now understands the linear and cyclic nature of time.”

Phillip Ewell

In an article for the journal Music Theory Online entitled “Music Theory and the White Racial Frame,” Ewell argues that “music theory is white [it is]” and the discipline is undergirded by a deep-seated ideology of White supremacy calculated to thwart Black and Brown (but strangely not East Asian) achievement in classical music. The main target of Ewell’s critique is the early twentieth-century music theorist Heinrich Schenker (1868–1935) who initiated the parsing of musical structures into foreground, middle-ground and background to tease out the tonal formulas that underpin large-scale movements. Drawing on poststructuralist critiques of Western civilization, Ewell claims this kind of score-driven analysis of musical works as part of Western musicology (what he dubs the “drive to scientificize music analysis”) represents an effort to “shore up whiteness in music theory’s white frame” and to insulate “whiteness from potential criticism.” In attacking Schenker (who was an Austrian Jew), Ewell inadvertently strayed into forbidden fields of inquiry and faced unexpectedly fierce blowback and accusations of “Black anti-Semitism.”

Ewell’s “white racial frame” purportedly extends to musical education where, in the most commonly used theory textbooks in the United States, only 1.63% of musical examples come from non-White composers. This is also problematic for Linda Shaver-Gleason because studying a particular piece “reaffirms its canonical status; enshrining it in a textbook is deeming it worthy of study.” Constantly referencing White composers “reinforces the idea that they’re the ones who deserve the most respect, as if to say, ‘Marvel at the many techniques Mozart used so perfectly!’” Ethan Hein, a (presumably Jewish) doctoral fellow in music education at NYU, likewise decries the stubbornness of music teachers in teaching “European-descended” classical music over that of “music descending from the vernacular traditions of the African diaspora.” Orienting music education towards the European classical tradition, an “implicit racial ideology,” is, he declares, “insidious” in its “affirmations of Whiteness.”

In 2020, college-level music pedagogy responded to Black Lives Matter by “dramatically reconsidering which composers and musical traditions we do and don’t discuss in the classroom.” Similar dynamics were at work within other musical institutions. The Metropolitan Opera, upon cancelling its 2020–21 season, announced that it would begin its next season with Black composer Terence Blanchard’s Fire Shut Up in My Bones, the first opera by a Black composer to appear on the Met’s stage. Despite such gestures, for Slate journalist Chris White, musicians, academics, and teachers still “have a lot of work ahead to confront the racist and sexist history of classical music.”

Music theory’s white racial frame is also sustained, according to Ewell, by the “citational chain” of white men citing other white men in the musicological literature. He wants to break this chain “in which whiteness begets whiteness and maleness begets maleness.” Meanwhile, Ewell’s own utterly conventional and establishment beliefs are the unreflective product of his engagement with a group of predominantly Jewish critical race and gender theorists: he borrowed the term “white racial frame” from Harvard sociology professor Joe Feagin. Arguing that the entire Western art music tradition is inherently White supremacist, Ewell advocates “overthrowing the existing structure and building a new one that would accommodate non-white music a priori [prior to listening to it??] — no reaching for ‘inclusion’ necessary because non-white composers would already be there.”

Beethoven and the “New Musicology”

Ewell postures as an outsider bravely challenging sinister norms entrenched in Western musicology when, in reality, his perspective has been utterly conventional since the advent of the “New Musicology” in late 1980s — when Cultural Marxists to a significant extent overran the discipline. Musicology was one of the last frontiers for poststructuralism and critical theory which had already infested most of the humanities and social sciences by the early 1980s. The New Musicology was founded by the Jewish-American critic and musicologist Joseph Kerman (born Zukerman) whose journalist father William Zukerman (1885–1961) was a prominent figure in the Jewish media and author of the 1937 book The Jew in Revolt: The Modern Jew in the World Crisis.

A key figure in the ascent of the “New Musicology” was Susan McClary whose 1991 book Feminine Endings: Music, Gender and Sexuality is considered a trailblazing text for the movement. McClary gained fame and notoriety for her feminist “analysis” of the first movement of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, where she claimed: “The point of recapitulation in the first movement of the Ninth is one of the most horrifying in music, as the carefully prepared cadence is frustrated, damming up energy which finally explodes in the throttling murderous rage of a rapist incapable of attaining release.” This risible statement was an elaboration of her belief the Western musical convention of sonata form is inherently sexist, misogynistic and imperialistic: that “tonality itself — with its process of instilling expectations and subsequently withholding promised fulfilment until climax — is the principle musical means during the period from 1600 to 1900 for arousing and channeling desire.” The primary “masculine” key (or first subject group) is said to represent the male self, and the secondary “feminine” key (or second subject group) represents the “other,” a territory to be explored and conquered, assimilated into the self and stated in the tonic home key.

Virtually all Cultural Marxist critiques of Western classical music fall back on these kind of entirely speculative metaphors. While purporting to offer additional insight into music, the New Musicology systematically imposes an anti-White male ideology on its subject, and, in this endeavor, happily discards all standards of proof and evidence. The conceit that, before the advent of the New Musicology, the discipline was limited to the rigid boundaries of empiricism and positivism is false; awareness of the context and reception of music has always been a core topic of musicology. There was, however, also a belief in purely musical elements and in the value of studying them. The problem with such “objective” technical analysis, for the likes of McClary and Ewell, is that it invariably leads to “White supremacist” conclusions about the relative quality of different musical traditions. The “problematic dimension” of analyzing “music as simply music,” McClary notes, is that people inevitably point to Western classical music “as evidence of the superiority of European and European-descended people, which marginalizes the rest of the world and, also, minority groups in the U.S.”

Constructing Beethoven as Black

The main alternative to the Cultural Marxist deconstruction (and proposed anti-White reconstruction) of the Western musical canon, has been attempts by Blacks to appropriate Beethoven for themselves. Given Beethoven’s status as the archetypical musical genius, it is unsurprising that aggrieved Blacks have, since the early twentieth century, attempted to propagate the myth that Beethoven had some African ancestry. The basis for this entirely spurious claim was the composer’s slightly swarthy complexion, and the fact part of his family traced its roots to Flanders, which was, for a period, under Spanish monarchical rule. Because Spain had a longstanding historical connection to North Africa through the Moors, a degree of blackness supposedly trickled down to the great composer — this despite the fact the Moors as an ethnic group weren’t even Black.

The myth was eagerly disseminated by Jamaican “historian” Joel Augustus Rogers (1880–1966) in works like Sex and Race (1941—44), the two-volume World’s Great Men of Color (1946–47), 100 Amazing Facts About the Negro (1934), Five Negro Presidents (1965), and Nature Knows No Color Line (1952). Rogers, whose intellectual rigor was basically non-existent, claimed that Beethoven — in addition to Thomas Jefferson, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Robert Browning, and several popes, among others — was genealogically African and thus Black. Despite being thoroughly debunked, the myth still lingers in contemporary culture: in 2007 Nadine Gordimer published a short story collection called Beethoven Was One-Sixteenth Black: And Other Stories. The determination, contrary to all available evidence, to make Beethoven Black is, of course, a desperate attempt to make the composer and his oeuvre a glorious symbol of Black accomplishment.

A pearl of wisdom from Jamaican historian Joel Augustus Rogers (1880–1966)

Otherwise sympathetic commentators have cautioned that such efforts are self-defeating, merely serving to treat the Western canon as fundamental and all other styles as deviations from this norm, thus reinforcing “the notion that of classical music as a universal standard and something that everyone should aspire to appreciate.” Trying to make Beethoven Black and desperately scouring the historical records for examples of non-Whites who wrote symphonies is to accept “a white-centric perspective that presents symphonies as the ultimate human achievement in the arts.”

Among those routinely cited by those desperate to prove the racial diversity of the Western art music tradition are the mixed-race composers Chevalier de Saint George, Samuel Coleridge-Taylor and George Bridgetower. These figures are remembered solely because they were non-White, not because of the excellence of their compositions. Beethoven personally knew Bridgetower, a talented violinist whose father was from the West Indies. Indeed, Bridgetower was the original dedicatee of one of Beethoven’s most celebrated violin sonatas. Beethoven called it the “mulatto sonata” after Bridgetower (before the word took on a more pejorative sense) and the pair gave the first performance but fell out soon afterwards, whereupon Beethoven renamed the piece for another violinist, Rudolphe Kreutzer.

Conclusion

Classical music, like other aspects of Western culture, has been a casualty of the anti-White diversity mania that now infests Western intellectual life. The Cultural Marxist critique of classical music (and of Beethoven) wallows in bad faith arguments and cognitive dissonance: Western classical music is nothing exceptional, yet cannot be invoked to praise White people because this necessarily implies the inferiority of other races; a White supremacist conspiracy thwarts Black and Brown achievement in the genre, but utterly fails to prevent East Asian interest and success; Black composers have written symphonies (and, indeed, Beethoven himself was Black), yet the Western classical music tradition is inherently White supremacist and needs radical deconstruction.

Ultimately, the reason the classical music canon (and Beethoven’s status as a titan of European civilization) is so keenly resented by anti-White activists, is because the gap in civilizational attainment it underscores is an embarrassing affront to regnant egalitarian assumptions. Western art music (with Beethoven as its leading exponent) stands as a glaring testament to the pre-eminence of European high culture, and implicitly of the race responsible for it. The attacks on Beethoven in 2020 are yet another example of warfare waged against White people through the construction of culture.

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, available here and here.

[1] Jan Swafford, The Vintage Guide to Classical Music: An Indispensable Guide for Understanding and Enjoying Classical Music (Knopf, 1993), 184-85.

[2] Romain Rolland, Beethoven the Creator (Rolland Press, 2008)

[3] Jan Swafford, Beethoven: Anguish and Triumph (Faber, 2015), 760.

[4] Lewis Lockwood, Beethoven: The music and the Life (Norton, 2005), 533.

Mystery writer Clark Howard’s history of the case,

Mystery writer Clark Howard’s history of the case,

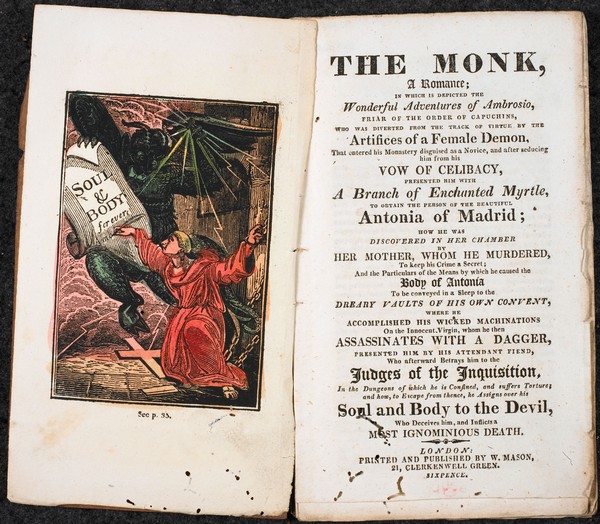

Early edition of The Monk by Matthew Lewis

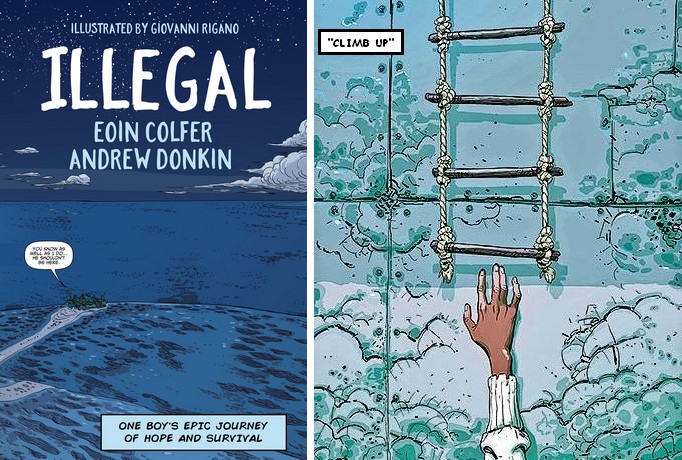

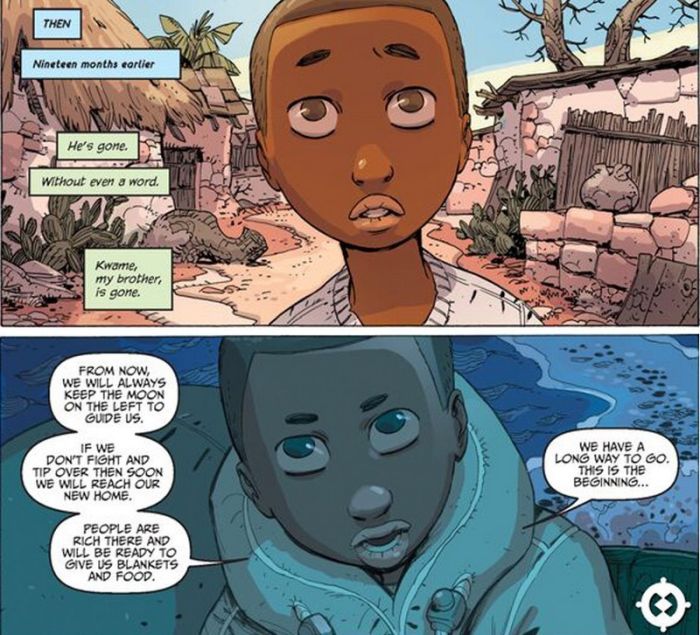

Early edition of The Monk by Matthew Lewis The blatantly sentimental and dishonest graphic novel Illegal (2017)

The blatantly sentimental and dishonest graphic novel Illegal (2017)

Ibram X. Kendi’s Anti-Racist Baby

Ibram X. Kendi’s Anti-Racist Baby