Tristan Tzara and the Jewish Roots of Dada — Part 2 of 3

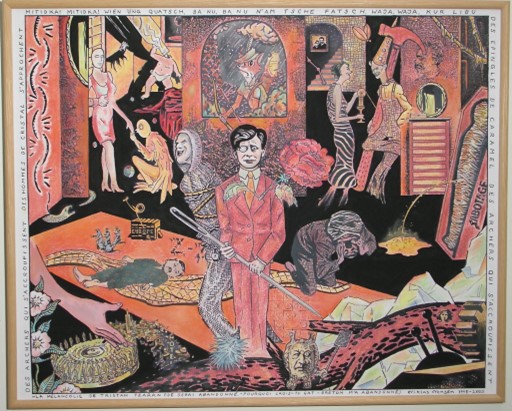

Tristan Tzara depicted in a contemporary painting

Tristan Tzara depicted in a contemporary painting

Go to Part 1.

Dada in Paris

By 1919, when Tzara left Switzerland to join the poet André Breton in Paris, he was, according to Richter, regarded as an “Anti-Messiah” and a “prophet”.[1] His 1918 Dada Manifesto had appeared in Paris, and, according to Breton, had “lit the touch paper. Tzara’s 1918 Manifesto was violently explosive. It proclaimed a rupture between art and logic, the necessity of the great negative task to accomplish; it praised spontaneity to the skies.”[2] The editors of the avant-garde literary review Littérature felt that Tzara could fill the gap left by the deaths of Guillaume Apollinaire and Jacques Vaché. Gale notes that “Tzara immediately became the most extreme contributor to Littérature,” and by the end of 1919, “the Littérature editors had to defend his work from nationalistic attacks in the Nouvelle Revue Française.”[3] A coordinated Dada insurgency was not, however, achieved until Tzara’s arrival in Paris in 1920.

In addition to his messianic zeal, Tzara brought to Paris Dada a skill in managing events and audiences, which transformed literary gatherings into public performances that generated enormous publicity. In the five months from January 1920 he helped organize six group performances, two art exhibitions and more than a dozen publications. Dempsey notes how “the popularity of these events with the public soon turned these revolutionary ‘anti-artists’ into celebrities. The cumulative effect of this first ‘Dada season’ as it became known, was to mark the movement as a nihilistic collective force leveled at the noblest ideals of advanced society.”[4] The performances with which Dadaists tested their Parisian audiences were consistently aggressive in nature, and psychological aggression characterized many of their artworks and journals. As one source notes: “Like the plays and stage appearances, individual works produced within Dada emanate a violent humor, ranging from vulgar to sacrilegious language to images of weapons and wounds, or references to taboos great and small: suicide, cannibalism, masturbation, vomiting.”[5]

Tzara (bottom left) with other Dada artists in Paris 1920

Tzara (bottom left) with other Dada artists in Paris 1920

It was widely observed at the time that the output of Paris Dada exhibited a “profound violence: physical hurt, damage to language, a wounding of pride or moral spirit,” that to native observers seemed wholly “uncharacteristic of French sensibility.”[6] Comoedia, a Parisian arts daily focused on theatre and cinema, soon became the central forum for debates over Dada and its effects on French audiences. Charges of enemy subversion, lunacy and charlatanism regularly appeared — just as it did in many German newspapers — pretexts to isolate what seemed to many a traitorous insurgency against bedrock national values.[7] Attacks on Dada in Paris soon took on an openly anti-Semitic tone when the French writer Jean Giraudoux, in explaining his rejection of Dada, pointed out: “I write in French, as I am neither Swiss nor Jewish and because I have all requisite honors and degrees.”[8]

The French cultural establishment looked askance at Dada from its arrival in Paris at the beginning of 1920. It was common knowledge that the Dadaists were avowed partisans of revolution and supported the communist uprisings in Berlin and Munich that had barely been put down. Trotsky’s red legions were, at that time, cutting a swathe of death and destruction in Poland, and many perceived a conjoined ethnic agenda behind Trotsky’s Bolshevism and Tzara’s Dada — especially given Dada’s appearance at socialist and anarchist venues throughout Paris. The connection was unambiguous in the mind of the Romanian nationalist Nicolae Rosu who noted that “Dadaism and French Surrealism exploit the moral and spiritual exhaustion of a war-torn society: the aggressive revolutionary currents in art seem to be an explosion of primal instincts detached from reason; post-war German socialism, largely developed by Jews, uses the opportunity of defeat to dictate the Weimar constitution (written by a Jew), and then through Spartakism, to install Bolshevism. Russian Bolshevism is the work of Jewish activists.”[9]

In October 1920, the messianic Jewish Dadaist Walter Serner arrived in Paris and reconvened with Tristan Tzara, who had just returned from his first visit to Romania since 1915. Serner’s campaign of shameless self-promotion, which included placing an advertisement in a Berlin newspaper describing himself as the world leader of Dada, was resented by Tzara, who was eager to establish his own priority as leader. By 1921, many of the original Dadaists had converged on Paris, and arguments among them created difficulties. By 1922, internal fighting between Tzara, Francis Picabia, and André Breton led to the dissolution of Dada.[10] Dada was officially ended in 1924 when Breton issued the first Surrealist Manifesto. Hans Richter claimed that “Surrealism devoured and digested Dada.”[11] Tzara distanced himself from Surrealism, disagreeing with its dream-centered Freudian dynamic, despite its anti-rationalism. Robert Short notes that

for Tzara, automatism [literary and artistic free association] was a visceral spasm, an explosion of the senses and the instinct that expressed the primitive and chaotic intensity in man and Nature. Where Surrealist automatism was introverted and sought to reveal patterns in the human unconscious, Dada art mimicked an objective chaos. … Surrealism was to prospect and exploit a vast substratum of mental resources which the Western cultural and economic tradition had deliberately tried to seal off. In place of science and reason, Surrealism was to cultivate the image and the analogy. In its efforts to restimulate the associative faculties of the mind, it turned its attention with respect and enthusiasm toward the thought processes of children and primitive peoples, towards the lyrical manifestations of lunacy and the synthesizing notions of occultism.[12]

Tzara also increasingly disagreed with the political orientation of Surrealism which evolved from the near-nihilist anarchism of the Dadaists to a strict adherence to the Communist Party line by the late 1920s, and then to Trotskyism following Breton’s personal meeting with Trotsky in Mexico in 1938.[13] Nonetheless, Tzara willingly reunited with Breton in 1934 to organize a mock trial of the Surrealist Salvador Dalí, who, at the time, was a confessed admirer of Hitler.[14]

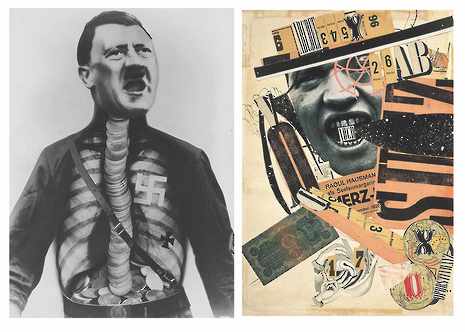

Left: Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk by John Heartfield (Herzfeld) (1923). Right: ABCD by Raoul Hausmann (1923—24)

Left: Adolf the Superman: Swallows Gold and Spouts Junk by John Heartfield (Herzfeld) (1923). Right: ABCD by Raoul Hausmann (1923—24)

Tzara’s own politics were profoundly radical, and with Hitler’s ascension to power in 1933 effectively marking the end of Germany’s avant-garde, Tzara threw his support behind the French Communist Party (the PCF). Codrescu notes that the secular Jews of Tzara’s parents’ generation “were capitalists whose practical materialism horrified Samuel. The French resistance to the Nazis was, of course, the reason he later joined the Communist Party, but there was also an oedipal reason for his joining the communists: as a mystic, he was viscerally opposed to capitalism. He had to kill his father.”[15] The allegiance of the great majority of Dadaists to Marxism was paradoxical given that Marxist dialectical materialism and forecast of the historical inevitability of communist revolution was based on a kind of mathematical rationalism that ran directly counter to the Dada spirit.

Tzara’s allegiance to Marxism-Leninism was reportedly questioned by the PCF and the Soviet authorities. This was because Tzara’s irregular vision of utopia made use of particularly violent imagery — shocking even by Stalinist standards.[16] Tzara backed Stalinism and rejected Trotskyism (at least publically), and unlike some of the leading Surrealists, even submitted to PCF demands for the adoption of socialist realism during the writers’ congress of 1935. Tzara nevertheless interpreted Dada and Surrealism as revolutionary currents, and presented them as such to the public.[17]

During World War II, Tzara took refuge from the German occupation forces by moving to the southern areas controlled by the Vichy regime. Back in Romania, he was stripped of Romanian citizenship, and his writings were banned by the Antonescu regime, along with 44 other Jewish-Romanian authors. In France, the pro-German publication Je Suis Partout made his whereabouts known to the Gestapo. In late 1940 or early 1941, he joined a group of anti-Nazi and Jewish refugees in Marseille who were seeking to flee Europe. Unable to escape occupied France, he joined the French Resistance and contributed to their published magazines, and managed the cultural broadcast for the Free French Forces clandestine radio station.

During 1945, he served under the Provisional Government of the French Republic as a representative to the National Assembly, and two years later received French citizenship. Tzara remained a spokesman for Dada, and in 1950 delivered a series of radio addresses discussing the topic of “the avant-garde revues in the origin of the new poetry.”[18] Towards the end of his life Tzara returned to his Jewish mystical roots, with Codrescu noting that “after the Second World War, after the Holocaust, after membership of the French Communist Party, Tzara returned to the Kabbalah.”[19]

In 1956, Tzara visited Hungary just as the hated government of Imre Nagy faced a popular revolt (with strong undercurrents of anti-Semitism), and while receptive of the Hungarians’ demand for political liberalization, did not support their emancipation from Soviet control, describing the independence demanded by local writers as “an abstract notion.” He returned to France just as the revolution broke out, triggering a brutal Soviet military response. Ordered by the PCF to be silent on these events, Tzara withdrew from public life, and dedicated himself to promoting the African art he had been collecting for years. He died in 1963 and was buried in the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris.

Dada in New York and Germany

According to the account of Marcel Duchamp, in late 1916 or early 1917 he and Francis Picabia received a book sent by an unknown author, one Tristan Tzara. The book was called The First Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine which had just been published in Zurich. In this work, Tzara declared Dada to be “irrevocably opposed to all accepted ideas promoted by the ‘zoo’ of art and literature, whose hallowed walls of tradition he wanted to adorn with multicolored shit.”[20] Duchamp later recalled: “We were intrigued but I didn’t know who Dada was, or even that the word existed.”[21] Tzara’s scatological message was the catalyst for the establishment of the antipatriotic and anti-rationalist Dada message in New York, and it may well have informed Duchamp’s decision to submit his infamous Fountain to the Society of Independent Artists in New York.

In 1917, Duchamp famously sent the Independent an upside-down urinal entitled Fountain, signing it R. Mutt (famously photographed by Alfred Stieglitz). By doing so, Duchamp directed attention away from the work of art as a material object, and instead presented it as an idea — shifting the emphasis from making to thinking. He later did the same with a bottle rack and other items. Through subversive gestures like these, Duchamp parodied the Futurist machine aesthetic by exhibiting untreated objets trouvés or readymade objects. To his great surprise, these readymades became accepted by the mainstream art world.

Marcel Duchamp’s Fountain (1917)

Alongside the Frenchman Marcel Duchamp (1887-1968) and the French-born Cuban Francis Picabia (1879-1953) were the American Jews Morton Schamberg (1881-1918) and Man Ray (1890-1977). The work of the New York Dadaists was focused around the gallery of the Jewish photographer Alfred Stieglitz and his publication 291, and the art collectors Walter and Louise Arensberg. Picabia later described this group as “a motley international band which turned night into day, conscientious objectors of all nationalities and walks of life into an inconceivable orgy of sexuality, jazz and alcohol.”[22] They hotly debated such topics as art, literature, sex, politics and psychoanalysis. Dada in New York stayed in contact with Dada in Zurich, though it ultimately failed to take hold, and in 1921 Man Ray wrote to Tzara, complaining that “Dada cannot live in New York. All New York is Dada and will not tolerate a rival, will not notice Dada.”[23]

Most of the artists of New York Dada left for Paris. Man Ray arrived there in July 1921, shortly after Duchamp, and remained there until 1940, becoming the youngest member of the Paris Dada group, and later of the Surrealists, even though this did not reflect any real modification of his art. With the arrival of Duchamp and Man Ray in Paris, New York Dada, which had not engaged in the kind of militant cultural protest seen in the European centers of Dada, came to an end. Their experiences were not dissimilar to those of other Dadaists “who were swept along, as they were, by the vehemence of André Breton into the coils of the new Surrealist movement which was, in many ways, an offspring of Dada.”[24]

Early in 1917, Richard Huelsenbeck, a twenty-four-year-old German medical student and poet, returned to Berlin from Zurich, where he had spent the preceding year in the company of the Zurich Dadaists under the leadership of Tristan Tzara. After the war ended, Dada activity in Germany increased as Dadaists dispersed to various sites throughout the country including, most prominently, Berlin, Cologne and Hanover. In Germany, alongside George Grosz, Walter Mehring, Johannes Baader, Hannah Höch and Kurt Schwitters were Jews like Johannes Baargeld (1876–1955), Raoul Hausmann (1886–1971), and Eli Lissitzky (1890–1941).

The political radicalism of the Berlin Dadaists was even more pronounced than that of the Zurich or Paris Dadaists, with most belonging to the League of Spartacus, a radical socialist group that became the German Communist Party in 1919. German Dada was also closer to the Eastern European avant-garde led by Jewish artists like Eli Lissitzky and László Moholy-Nagy. The new Soviet state that emerged after the Bolshevik Revolution initially adopted a policy in favor of radical experimentation. In Berlin, more than anywhere outside the Soviet Union, “a direct equation could be made between political reform and artistic radicalism. Despite the seeming absurdity of some of their activities, the Dadas’ reinvention of poetic language and artistic form could be seen as a prelude to reforming the whole of the decayed social system.”[25] A Dada Manifesto by Huelsenbeck and Hausmann, published in a Cologne newspaper, declared that Dada “is German Bolshevism”[26] and that “Dadaism demands: the international revolutionary union of all creative and intellectual men and women on the basis of radical Communism.” [27]

The Berlin Dadaists even condemned the Weimar Republic as representing a renaissance of “Teutonic barbarity,” and held Communism to be the best hope for freedom.[28] Robert Short notes that, among the German Dadaists, were those for whom “Dada was a political weapon and those for whom communism was a Dadaistical weapon. There was a faction which saw anarchy and anti-art as a sufficient programme in itself, and a second faction which saw anarchy as a provisional precondition for the introduction of new values.”[29]

Falling into the latter category was Johannes Baargeld. Born Alfred Emanuel Ferdinand Gruenwald to a prosperous Romanian-Jewish insurance director, “Baargeld” was the ironic, leftist pseudonym he adopted (Baargeld being the German word for cash or ready money). Growing up in Cologne in a wealthy home, he was exposed from a young age to contemporary art and culture, beginning with his parents’ collection of modernist paintings. He joined the Independent Socialist Party of Germany (USPD) — the radical left wing of the Socialist Party — and in the process “turned his back on his wealthy bourgeois upbringing and became actively involved in the leadership of the Rhineland Marxists.”[30]

Baargeld (also called “Zentrodada”) and Max Ernst cofounded Dada in Cologne in the summer of 1919. Baargeld’s father was anxious about his son’s political leanings and sought Ernst’s help. Robert Short notes that: “They succeeded in convincing him that Dada went further than Communism and that its combination of new-found inner freedom and powerful external expression could do more to set the whole world free. In return, Grunewald senior financed the publication of a new international Dada magazine Die Schammade.”[31]

In April 1920, Cologne Dada staged one of the most memorable of German Dada’s exhibitions. Entered by way of a public lavatory, it included “exhibits” like a young girl in communion dress reciting obscene verses, and a bizarre object by Baargeld consisting of an aquarium filled with red fluid from which protruded a polished wooden arm and on whose surface floated a head of woman’s hair.[32] The First International Dada Fair was held in Berlin in June 1920, and was the most significant Dadaist event organized in the Berlin milieu. The radical political orientation of the organizers was illustrated by a mannequin of a German officer with the head of a pig hanging from the ceiling with a notice “Hanged by the revolution,” which triggered fierce debate about its subversive and anti-military character.[33]

The First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920

The First International Dada Fair in Berlin in 1920

Given such provocative gestures and the extensive Jewish participation in Dada, it was not surprising that, between the two world wars, German nationalists linked Dada (and avant-gardism generally) to Jews, claiming these modern trends aimed to destroy the principles of classical beauty and eradicate national traditions. The Dadaists were said to express the “nihilistic Jewish spirit” (a common phrase at the time), if they were not actually mad. In response to the activities of Jewish Dadaists, “calls for ‘degenerate’ art to be banned were widely published in pre-Nazi and later in Nazi Germany, as well as in France.”[34]

Interestingly, Mein Kampf was composed by Hitler at the time of Paris Dada’s existence, and his comments about Jewish influence on Western art need be understood in this context. He mentions the “artistic aberrations which are classified under the names of Cubism and Dadaism,” and clearly has the Dadaists in mind when he observes that “Culturally, his [the Jew’s] activity consists in bowdlerizing art, literature and the theatre, holding the expressions of national sentiment up to scorn, overturning all concepts of the sublime and the beautiful, the worthy and the good, finally dragging the people to the level of his own low mentality.”[35] Likewise, when he recalls how he once asked himself whether “there was any shady undertaking, any form of foulness, especially in cultural life, in which at least one Jew did not participate?,” he subsequently discovered that “On putting the probing knife carefully to that kind of abscess one immediately discovered, like a maggot in a putrescent body, a little Jew who was often blinded by the sudden light.”[36]

In 1933, Hitler’s new government announced that: “The custodians of all public and private museums are busily removing the most atrocious creations of a degenerate humanity and of a pathological generation of ‘artists.’ This purge of all works marked by the same western Asiatic stamp has been set in motion in literature as well with the symbolic burning of the most evil products of Jewish scribblers.”[37] At the exhibition of degenerate art held in Munich in 1937 the Dadaist works were considered the most degenerate of all — the epitome of Kulturbolschewismus. In that year the Ministry for Education and Science published a pamphlet in which Dr. Reinhold Krause, a leading educator, wrote that “Dadaism, Futurism, Cubism, and other isms are the poisonous flower of a Jewish parasitical plant.”[38]

Hitler and Goebbels at the Degenerate Art Exhibition of 1937

British historian Paul Johnson points out that: “Hitler always referred to degenerate art as ‘Cubism and Dadaism’, maintaining that it started in 1910, and the ‘Degenerate Art’ exhibition bore a curious resemblance to the big Dada shows of 1920-22, with a lot of writing on the walls and paintings hung without frames.”[39] He also notes that the Nazi campaign against “degenerate art” was “the best thing that could possibly have happened, in the long term, to the Modernist Movement.” This is because since the Nazis, universally reviled by all governments and cultural establishments since 1945, tried to destroy and suppress such art completely, then its merits were self-evident morally, and anything the Nazis opposed was assumed to have merit — on the illogical basis that the enemy of my enemy must be my friend. “These factors,” notes Johnson, “so potent in the second half of the twentieth century, will fade during the twenty-first, but they are still determinant today.”[40]

The Legacy of Dada

Dada’s destructive influence has been seminal and long-lasting. As Dempsey points out, Dada’s notion that: “The presentation of art as idea, its assertion that art could be made from anything and its questioning of societal and artistic mores, irrevocably changed the course of art.”[41] The movement represented “an assertive debunking of the ideas of technical skill, virtuoso technique, and the expression of individual subjectivity. … Dada’s cohesion around these procedures points to one of its primary revolutions — the reconceptualization of artistic practice as a form of tactics.”[42] These tactics consisting, variously, of “intervention into governability, that is, subversions of cultural forms of social authority — breaking down language, working against various modern economies, willfully transgressing boundaries, mixing idioms, celebrating the grotesque body as that which resists discipline and control.”[43]

Dada’s iconoclastic force had enormous influence on later twentieth-century conceptual art. Godfrey notes that: “Dada can be seen as the first wave of conceptual art” which exercised an enormous influence on subsequent art movements. [44] In the late 1950s and 1960s, in opposition to the then dominant Abstract Expressionism and Post-Painterly Abstraction, Robert Rauschenberg and Jasper Johns resurrected the Dadaist tradition, describing the works they produced as “Neo-Dada” — a movement that, together with the “pre-emptive kitsch” of Pop Art, effectively relaunched the conceptual art of the original Dadaists, and which has plagued Western art ever since. The Neo-Dadaists themselves left a deeply influential Cultural Marxist legacy insofar as their

visual vocabulary, techniques, and above all, their determination to be heard, were adopted by later artists in their protest against the Vietnam War, racism, sexism, and government policies. The emphasis they laid on participation and performance was reflected in the activism that marked the politics and performance art of the late 1960s; their concept of belonging to a world community anticipated sit-ins, anti-war protests, environmental protests, student protests and civil rights protests that followed later.[45]

Another pernicious influence of Dada stemmed from its rejection of the identity between art and beauty. Crepaldi notes that “many artists before Dada had called into question the aesthetic canons of their contemporaries and had proposed other canons, destined to meet varying degrees of success.” The Dadaists went beyond this, and called into question “the notion according to which the goal of art is the expression of a value called ‘beauty.’”[46]

The Dadaists thus legitimized the idea that the artist has a right (nay a duty) to produce ugly works, and instituted a cult of ugliness in the arts that has since eroded the cultural self-confidence of the West.

Go to Part 3.

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, banned by Amazon, but available here.

[1] Richter, Dada. Art and Anti-art, 168.

[2] Fiona Bradley, Movements in Modern Art — Surrealism (London: Tate Gallery Publishing, 2001), 18-19.

[3] Gale, Dada & Surrealism, 180.

[4] Janine Mileaf & Matthew Witkovsky, “Paris,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 349.

[5] Ibid., 358.

[6] Ibid., 350.

[7] Ibid., 352.

[8] Ibid., 366.

[9] Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess, 174.

[10] Dempsey, Styles, Schools and Movements — An Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art, 119.

[11] Richter, Dada — Art and Anti-art, 119.

[12] Robert Short, Dada and Surrealism (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1994), 69; 83.

[13] Patrick Waldberg, Surrealism (London: Thames & Hudson, 1997), 18.

[14] Carlos Rojas, Salvador Dalí, or the Art of Spitting on Your Mother’s Portrait (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1993), 98.

[15] Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess, 215.

[16] Beitchman, I Am a Process with No Subject, 48-9.

[17] Irina Livezeanu, “From Dada to Gaga: The Peripatetic Romanian Avant-Garde Confronts Communism,” Mihai Dinu Gheorghiu & Lucia Dragomir (Eds.), Littératures et pouvoir symbolique (Bucharest: Paralela 45, 2005), 245-6.

[18] Hockensmith, “Artists’ Biographies,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 489.

[19] Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess, 211.

[20] Michael Taylor, “New York,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 287.

[21] Pierre Cabanne, Duchamp & Co., (Paris: Finest SA/Editions Pierre Terrail, 1997), 115.

[22] Taylor, “New York,” 278.

[23] Hockensmith, “Artists’ Biographies,” 479.

[24] Schnapp, Art of the Twentieth Century — 1900-1919 — The Avant-garde Movements, 412.

[25] Gale, Dada & Surrealism, 120.

[26] Bernard Blisténe, A History of Twentieth Century Art (Paris: Fammarion, 2001), 62.

[27] Dawn Ades, “Dada and Surrealism,” David Britt (Ed.) Modern Art — Impressionism to Post-Modernism, (London, Thames & Hudson, 1974), 222.

[28] Edina Bernard, Modern Art — 1905-1945 (Paris: Chambers, 2004), 86.

[29] Robert Short, Dada and Surrealism (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1994), 42.

[30] Doherty, “Berlin,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 220.

[31] Short, Dada and Surrealism, 42.

[32] Robert Short, Dada and Surrealism (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1994), 50.

[33] Schnapp, Art of the Twentieth Century — 1900-1919 — The Avant-garde Movements, 399.

[34] Philippe Dagen, “From Dada to Surrealism — Review” (The Guardian, July 19, 2011). http://www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/jul/19/dada-to-surrealism-dagen-review

[35] Adolf Hitler, Mein Kampf (trans. By James Murphy), (London: Imperial Collegiate Publishing, 2010), 281.

[36] Ibid., 58.

[37] Peter Adam, Arts of the Third Reich (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1992), 55.

[38] Ibid., 12-15.

[39] Paul Johnson, Art — A New History (New York: HarperCollins, 2003), 707.

[40] Ibid., 709.

[41] Dempsey, Styles, Schools and Movements — An Encylopaedic Guide to Modern Art, 119.

[42] Dickerman, “Introduction & Zurich,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 8.

[43] Ibid., 11.

[44] Godfrey, Conceptual Art, 37.

[45] Dempsey, Styles, Schools and Movements — An Encyclopedic Guide to Modern Art, 204.

[46] Gabriel Crepaldi, Modern Art 1900-1945 — The Age of the Avant-Gardes (London: HarperCollins, 2007) 195.

You stand in front of it in amazement and ask yourself, “Is this art?”

“Of course it’s art!” says the Jew, “And as long as you don’t grasp that, you’re an anti-Semite, racist and Nazi!”

Mr. Sanderson is expressly thanked for this elaborate work of clarification.

“Die Schammade” = the shame(less) maggot

Fits to the name of Jew “Morton Schamberg”

(Schamberg/Schamhügel means Mons pubis)

The link to the author’s book at the end says “Uh-oh, not available.” It is a Walmart site!

Please post a viable link for the book in the comments or edit the original essay.

I’ll ask him about it. Walmart must have gotten the memo.

A BookFinder search suggests that there are eight copies, perhaps a few more, of Dr. Sanderson’s book now available for purchase in the world, Karl. I shouldn’t be in the least surprised were this to turn out to be true.

The cult of ugly, from the ugly people who are at war with beauty.

Because god and nature represent beauty and (((these))) are godless freaks who have done nothing except profane and fight against god

Thank you for this excellent study.

There would be so much to say about it, but I will remain concise.

I vaguely knew this pseudo-artistic but real subversive garbage, Dadaism, and its initiator “tzara”, but without knowing all the details – these Jewish misdeeds being so tiresome in their recurrence.

Obviously this Tzara cumulates all the stereotypes : hatred for the white race and his achievements , envy, charlatanism, obsession for the ugly, the primitive… Negro fetishism, scatology, etc etc

Another example of Jewish pathology.

I don’t think that these sorts of Jews wish to tear down Israeli society.

No, just Western society.

“Seeds of Peace”

Dada-Dieter back on track in the middle of Wokland.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YU-Qw8gR9HM

He followed the midget into another universe.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iVkt7j9j9Fc

As several of the individuals included in the 1920 Paris group photo grew out of their Dadaist follies and excesses and still retain, at least in France, a certain measure of acclaim, it might be useful to identify them all: front row (l to r): Tristan Tzara, Céline Arnauld, Francis Picabia, André Breton; middle row (l to r): Paul Dermée, Philippe Soupault, Georges Ribemont-Dessaignes; back row (l to r): Louis Aragon, Theodore Fraenkel, Paul Éluard, Emmanuel Faÿ. Four of the eleven pictured—Tzara, Arnauld, Fraenkel, Faÿ—are Jews.

Everything about cultural marxism is a retrogression to the lowest common denominator. Under cultural marxism the superior have to be surpressed lest they offend the mediochre intelligence and poor sensibilities of the inferior. Cultural marxism is a big middle finger to anyone who has ever strove for godliness and human perfection.