Tristan Tzara and the Jewish Roots of Dada — Part 1 of 3

Tristan Tzara (Samuel Rosenstock)

The twentieth century saw a proliferation of art inspired by the Jewish culture of critique. The exposure and promotion of this art grew alongside the Jewish penetration and eventual capture of the Western art establishment. Jewish artists sought to rewrite the rules of artistic expression — to accommodate their own technical limitations and facilitate the creation (and elite acceptance) of works intended as a rebuke to Western civilizational norms.

The Jewish intellectual substructure of many of these twentieth-century art movements was manifest in their unfailing hostility toward the political, cultural and religious traditions of Europe and European-derived societies. I have examined how the rise of Abstract Expressionism exemplified this tendency in the United States and coincided with the usurping of the American art establishment by a group of radical Jewish intellectuals. In Europe, Jewish influence on Western art reached a peak during the interwar years. This era, when the work of many artists reflected their radical politics, was the heyday of the Jewish avant-garde.

A prominent example of a cultural movement from this time with important Jewish involvement was Dada. The Dadaists challenged the very foundations of Western civilization which they regarded, in the context of the destruction of World War One, and continuing anti-Semitism throughout Europe, as pathological. The artists and intellectuals of Dada responded to this socio-political diagnosis with assorted acts of cultural subversion. Dada was a movement that was destructive and nihilistic, irrational and absurdist, and which preached the overturning of every cultural tradition of the European past, including rationality itself. The Dadaists “aimed to wipe the philosophical slate clean” and lead “the way to a new world order.”[1] While there were many non-Jews involved in Dada, the Jewish contribution was fundamental to shaping its intellectual tenor as a movement, for Dada was as much an attitude and way of thinking as a mode of artistic output.

Writing for The Forward, Bill Holdsworth observed that Dada “was one of the most radical of the art movements to attack bourgeois society,” and that at “the epicenter of what would become a distinctive movement… were Romanian Jews — notably Marcel and Georges Janco and Tristan Tzara — who were essential to the development of the Dada spirit.”[2] For Menachem Wecker, the works of the Jewish Dadaists represented “not only the aesthetic responses of individuals opposed to the absurdity of war and fascism” but, invoking the well-worn light-unto-the-nations theme, insists they brought a “particularly Jewish perspective to the insistence on justice and what is now called tikkun olam.” Accordingly, for Wecker, “it hardly seems a coincidence that so many of the Dada artists were Jewish.”[3]

It does seem hardly coincidental when we learn that Dada was a genuinely international event, not just because it operated across political frontiers, but because it consciously attacked patriotic nationalism. Dada sought to transcend national boundaries and deride European nationalist ideologies, and within this community of artists in exile (a “double Diaspora” in the case of the Jewish Dadaists) what mattered most was the collective effort to articulate an attitude of revolt against European cultural conventions and institutional frameworks.

First and foremost, Dada wanted to accomplish “a great negative work of destruction.” Presaging the poststructuralists and deconstructionists of the sixties and seventies, they believed the only hope for society “was to destroy those systems based on reason and logic and replace them with ones based on anarchy, the primitive and the irrational.”[4] Robert Short notes that Dada stood for “exacerbated individualism, universal doubt and [an] aggressive iconoclasm” that sought to debunk the traditional Western “canons of reason, taste and hierarchy, of order and discipline in society, of rationally controlled inspiration in imaginative expression.”[5]

Tristan Tzara and Zurich Dada

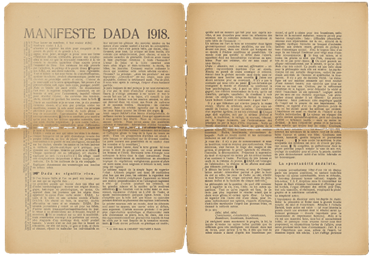

The man who effectively founded Dada was the Romanian Jewish poet Tristan Tzara (born Samuel Rosenstock in 1896). “Tristan Tzara” was the pseudonym he adopted in 1915 meaning “sad in my country” in French, German and Romanian, and which, according to Gale, was “a disguised protest at the discrimination against Jews in Romania.”[6] It was Tzara who, through his writings, most notably The First Heavenly Adventure of Mr. Antipyrine (1916) and the Seven Dada Manifestos (1924), laid the intellectual foundations of Dada.[7] Tzara’s Dadaist Manifesto of 1918, was the most widely distributed of all Dada texts, and “played a key role in articulating a Dadaist ethos around which a movement could cohere.”[8]

Tzara’s Dada Manifesto of 1918

In his book Dada East: The Romanians of Cabaret Voltaire, Tom Sandqvist notes that Tzara’s intellectual and spiritual background was infused with the Yiddish and Hassidic subcultures of his early twentieth-century Moldavian homeland, and how these were of seminal importance in determining the artistic innovations he would institute as the leader of Dada. He links Tzara’s revolt against European social constraints directly to his Jewish identity, and his perception of the Jewish population of Romania (and particularly of his native Moldavia) was cruelly oppressed by anti-Semitism. Under Romanian law, the Rosenstocks, a family of prosperous timber merchants, were not fully emancipated. Many Russian Jews settled in Romanian Moldova after being driven out of other countries and lived there as guests of the local Jews who only became Romanian citizens after the First World War (as a condition for peace set by the Western powers). For Sandqvist, the treatment of Jews in Romania fueled an attitude of revolt against the socio-political status quo in Tzara, and this was fully consistent with the anarchist impulses he exhibited at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich and later in Paris.

Agreeing with this thesis, the ethnocentric Jewish poet and Dada historian, Andrei Codrescu, claims the supposedly ubiquitous anti-Semitism suffered by Romanian Jews like Tzara extends into the present day, insisting: “The Rosenstocks were Jews in an anti-Semitic town that to this day does not list on its website the founder of Dada among the notables born there.” This is considered all the more egregious given that, despite its marginality, Tzara’s hometown Moineşti is, in Codrescu’s opinion, “the center of the modern world, not only because of Tristan Tzara’s invention of Dada, but because its Jews were among the first Zionists, and Moineşti itself was the starting point of a famous exodus of its people on foot from here to the land of dreams, Eretz-Israel.” For Codrescu, Tzara’s Jewish heritage was of profound importance in shaping his contribution to Dada.

The daddy of dada was welcomed at his bar mitzvah in 1910 into the Hassidic community of Moineşti-Bacau by the renowned rabbi Bezalel Zeev Safran, the father of the great Chief Rabbi Alexandre Safran, who saw the Jews of Romania through their darkest hour during the fascist regime and the Second World War. Sammy Rosenstock’s grandfather was the rabbi of Chernowitz, the birthplace of many brilliant Jewish writers, including Paul Celan and Elie Weisel [both of whom wrote about the Holocaust]. … Sammy’s father owned a saw-mill, and his grandfather lived on a large wooded estate, but his family roots were sunk deeply into the mud of the shtetl, a Jewish world turned deeply inward.[9]

For Codrescu, Tzara was one of the many “shtetl escapees” who was “quick to see the possibility of revolution,” and he became a leader within “the revolutionary avant-garde of the 20th century which was in large measure the work of provincial East European Jews.” Crucially, for shaping the intellectual tenor of Dada, Tzara and the other Jewish exiles from Bucharest like the Janco brothers “brought along, wrapped in refugee bundles, an inheritance of centuries of ‘otherness.’”[10] This sense of “otherness” was rendered all the more politically and culturally potent given the “messianic streak [that] drove many Jews from within.” Codrescu notes that: “By the time of Samuel’s birth in 1896, powerful currents of unrest were felt within the traditional Jewish community of Moineşti. The questions of identity, place and belonging, which had been asked innumerable times in Jewish history, needed answers again, 20thcentury answers.”[11] In this need for answers lay the seeds of Dada as a post-Enlightenment (proto-postmodern) manifestation of Jewish ethno-politics.

Tristan Tzara in Romania in 1912 (far left) with Marcel and Jules Janco (third and fourth from left)

While there is some controversy over who exactly invented the name “Dada,” most sources accept that Tzara hit upon the word (which means hobbyhorse in French) by opening a French-German dictionary at random. “Da-da” also means “yes, yes” in Romanian and Russian, and the early Dadaists reveled in the primal quality of its infantile sound, and its appropriateness as a symbol for “beginning Western civilization again at zero.” Crepaldi notes how the choice of the group’s name was “emblematic of their disillusionment and their attitude, deliberately shorn of values and logical references.”[12] Tzara seems to have recognized its propaganda value early with the German Dadaist poet Richard Huelsenbeck recalling that Tzara “had been one of the first to grasp the suggestive power of the word Dada,” and developed it as a kind of brand identity.[13]

Tzara’s own “Dadaist” poetry was marked by “extreme semantic and syntactic incoherence.”[14] When he composed a Dada poem he would cut up newspaper articles into tiny fragments, shake them up in a bag, and scatter them across the table. As they fell, they made the poem; little further work was called for. With regard to such practices, the Jewish Dadaist painter and film-maker Hans Richter commented that “Chance appeared to us as a magical procedure by which we could transcend the barriers of causality and conscious volition, and by which the inner ear and eye became more acute. … For us chance was the ‘unconscious mind,’ which Freud had discovered in 1900.”[15] Codrescu speculates that Tzara’s aleatoric poetry had its likely intellectual and aesthetic wellspring in the mystical knowledge of his Hassidic heritage, where Tzara was inspired by:

the commentaries of other famous Kabbalists, like Rabbi Eliahu Cohen Itamari of Smyrna, who believed that the Bible was composed of an “incoherent mix of letters” on which order was imposed gradually by divine will according to various material phenomena, without any direct influence by the scribe or the copier. Any terrestrial phenomenon was capable of rearranging the cosmic alphabet toward cosmic harmony. A disciple of the Smyrna rabbi wrote, “If the believer keeps repeating daily, even one verse, he may obtain salvation because each day the order of the letters changes according to the state and importance of each moment … .”

An old midrashic commentary holds that repeating everyday even the most seemingly insignificant verse of the Torah has the effect of spreading the light of divinity (consciousness) as much as any other verse, even the ones held as “most important,” because each word of the Law participates in the creation of a “sound world,” superior to the material one, which it directs and organizes. This “sound world” is higher on the Sephiroth (the tree of life that connects the worlds of humans with God), closer to the unnamable, being illuminated by the divine. One doesn’t need to reach far to see that the belief in an autonomous antiworld made out of words is pure Dada. In Tzara’s words, “the light of a magic hard to seize and to address.”[16]

That Tzara returned to study of the Kabbalah towards the end of his life certainly lends weight to Codrescu’s thesis. Finkelstein notes how Tzara’s poetry “sounds eerily like a Kabbalistic ritual rewritten as a Dadaist café performance,” and links Tzara’s Dadaist spirit to the influence of the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Jewish heresies that were centered on the notion of “redemption through sin” which involved “the violation of Jewish law (sometimes to the point of apostasy) in the name of messianic transformation.” The Jewish-American poet Jerome Rothenberg calls these heresies “libertarian movements” within Judaism and connects them to Jewish receptivity to the forces of secularization and modernity, leading in turn to the “critical role of Jews and ex-Jews in revolutionary politics (Marx, Trotsky etc.) and avant-garde poetics (Tzara, Kafka, Stein etc.).” Rothenberg sees “definite historical linkages between the transgressions of messianism and the transgressions of the avant-garde.”[17] Heyd endorses this thesis, observing that: “Tzara uses terminology that is part and parcel of Judaic thinking and yet subjects these very concepts to his nihilistic attack.”[18] Perhaps not surprisingly, the Kabbalist and Surrealist author Marcel Avramescu, who wrote during the 1930s, was directly inspired by Tzara.

Nicholas Zarbrugg has written detailed studies of the ways that Dada fed into the sound and visual poetry of the first phase of postmodernism.[19] Tzara’s poetry was, for instance, to strongly influence the Absurdist drama of Samuel Beckett, and the poetry of Andrei Codrescu, Jerome Rothenberg, Isidore Isue, and William S. Burroughs. Allen Ginsberg, who encountered Tzara in Paris in 1961, was strongly influenced by Tzara. Codrescu relates that: “A young Allen Ginsberg, seated in a Parisian café in 1961, saw a sober-looking, suited Tzara hurrying by, carrying a briefcase. Ginsburg called to him “Hey Tzara!” but Tzara didn’t so much as look at him, unsympathetic to the unkempt young Americans invading Paris again for cultural nourishment.” For Codrescu, it was a minor tragedy that “the daddy of Dada failed to connect with the daddy of the vast youth movement that would revive, refine and renew Dada in the New World.”[20]

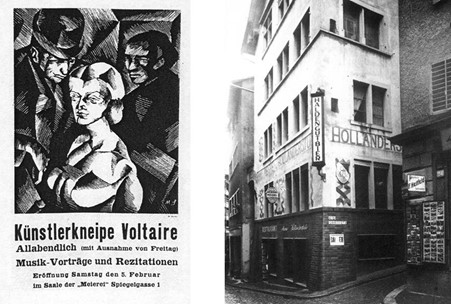

The Cabaret Voltaire

The Cabaret Voltaire was created by the German anarchist poet and pianist Hugo Ball in Zurich in 1916. Rented from its Jewish owner, Jan Ephraim, and with start-up funds provided by a Jewish patroness, Käthe Brodnitz, the Cabaret was established in a seedy part of the city and intended as a place for entertainment and avant-garde culture, where music was played, artwork was exhibited, and poetry was recited. Some of this poetry was later published in the Cabaret’s periodical entitled Dada, which soon became Tristan Tzara’s responsibility. In it he propagated the principles of Dadaist derision, declaring that: “Dada is using all its strength to establish the idiotic everywhere. Doing it deliberately. And is constantly tending towards idiocy itself. … The new artist protests; he no longer paints (this is only a symbolic and illusory reproduction).”[21]

Left: Poster for the Cafe Voltaire, Zurich 1916 / Right: Spiegelgasse 1, Zurich, Location of the Cabaret Voltaire

Evenings at the Cabaret Voltaire were eclectic affairs where “new music by Arnold Schoenberg and Alban Berg took its turn with readings from Jules Laforgue and Guillaume Apollinaire, demonstrations of ‘Negro dancing’ and a new play by Expressionist painter and playwright Oskar Kokoschka.”[22] The inclusion of dance and music extended Dada activities into areas that allowed a total expression approaching the pre-war (originally Wagnerian) ideal of the Gesamtkunstwerk (combined art work). In time the tone of the acts “became more aggressive and violent, and a polemic against bourgeois drabness began to be heard.”[23] Performances sought to shock bourgeois attitudes and openly undermine spectator’s templates for understanding culture. Thus, a June 1917 lecture “on modern art” was delivered by a lecturer who stripped off his clothes in front of the audience before being arrested and jailed for performing obscene acts in public.[24] Godfrey notes that: “This was carnival at its most grotesque and extreme: all the taste and decorum that maintains polite society was overturned.”[25] Robert Wicks:

The Dada scenes conveyed a feeling of chaos, fragmentation, assault on the senses, absurdity, frustration of ordinary norms, pastiche, spontaneity, and posed robotic mechanism. They were scenes from a madhouse, performed by a group of sane and reflective people who were expressing their decided anger and disgust at the world surrounding them.[26]

The outrages committed by Dadaists attacking the traditions and preconceptions of Western art, literature and morality were deliberately extreme and designed to shock, and this tactic extended beyond the Cabaret Voltaire to everyday gestures. For instance, Tzara, “the most demonic activist” of Dada, regularly appalled the dowagers of Zurich by asking them the way to the brothel. For Godfrey, such gestures are redolent of the “propaganda of the deed” of the violent anarchists who, through their random bombings and assassinations of authority figures, sought to “show the rottenness of the system and to shock that system into crisis.”[27] Arnason likewise underscores the serious ideological intent behind such gestures, noting that: “From the very beginning, the Dadaists showed a seriousness of purpose and a search for a new vision and content that went beyond any frivolous desire to outrage the bourgeoisie. … The Zurich Dadaists were making a critical re-examination of the traditions, premises, rules, logical bases, even the concepts of order, coherence, and beauty that had guided the creation of the arts throughout history.”[28] Jewish Frankfurt School intellectual Walter Benjamin, spoke admiringly of Dada’s moral shock effects as anticipating the technical effects of film in the way they “assail the spectator.”[29]

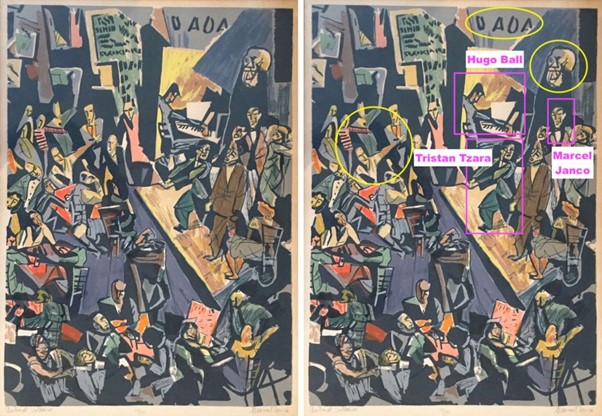

Left: Color lithograph of a painting by Marcel Janco from 1916, “Cabaret Voltaire”; Right: annotations identifying portrayals of Dada artists within the painting

The leadership of Zurich Dada soon passed from Ball to Tzara, who, in the process, “impressed upon it his negativity, his anti-artistic spirit and his profound nihilism.” Soon Ball could no longer identify with the movement and left, remarking: “I examined my conscience scrupulously, I could never welcome chaos.”[30] He moved to a small Swiss village and, from 1920, became removed from social and political life, returning to a devout Catholicism and plunging into a study of fifth- and sixth-century saints. Ball later embraced German nationalism and was to label the Jews “a secret diabolical force in German history,” and when analyzing the potential influence of the Bolshevik Revolution on Germany, concluded that, “Marxism has little prospect of popularity in Germany as it is a ‘Jewish movement.’”[31] Noting the makeup of the new Bolshevik Executive Committee, Ball observed that:

there are at least four Jews among the six men on the Executive Committee. There is certainly no objection to that; on the contrary, the Jews were oppressed in Russia too long and too cruelly. But apart from the honestly indifferent ideology they share and their programmatically material way of thinking, it would be strange if these men, who make decisions about expropriation and terror, did not feel old racial resentments against the Orthodox and pogrommatic Russia.[32]

Tzara, as Ball’s successor, quickly converted Ball’s persona as cabaret master of ceremonies into a role as a savvy media spokesman with grand ambitions. Tzara was “the romantic internationalist” of the movement according to Richard Huelsenbeck in his 1920 history of Dada, “whose propagandistic zeal we have to thank for the enormous growth of Dada.”[33]

In addition to the Jewish mysticism of his Hassidic roots, Tzara was strongly influenced by the Italian Futurists, though, not surprisingly, he rejected the proto-Fascist stance of their leader Marinetti. By 1916, Dada had replaced Futurism as the vanguard of modernism, and according to Jewish Dadaist Hans Richter, “we had swallowed Futurism — bones, feathers and all. It is true that in the process of digestion all sorts of bones and feathers had been regurgitated.”[34]

Nevertheless, the Dadaists’ intent was contrary to that of the Futurists, who extolled the machine world and saw in mechanization, revolution and war the logical means, however brutal, to solving human problems. Dada was never widely popular in the birthplace of Futurism, although quite a few Italian poets became Dadaists, including the poet, painter and future racial theorist Julius Evola, who became a personal friend of Tzara and initially took to Dada with unbridled enthusiasm. He eventually became disillusioned by Dada’s total rejection of European tradition, however, and began the search for an alternative, pursuing a path of philosophical speculation which later led him to esotericism and fascism.[35]

The entry of Romania into the war on the side of Britain, France, and Russia in August 1916 immediately transformed Tzara into a potential conscript. Gale relates that: “In November Tzara was called for examination by a panel ascertaining fitness to fight. He successfully feigned mental instability and received a certificate to that effect.”[36] At this time, living across the street from the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich were Lenin, Karl Radek and Gregory Zinoviev who were preparing for the Bolshevik Revolution.

After the November 1918 Armistice, Tzara and his colleagues began publishing a Dadaist journal called Der Zeltweg aimed at popularizing Dada at time when Europe was reeling from the impact of the war, the Bolshevik Revolution, the Spartacist uprising in Berlin, the communist insurrection in Bavaria, and, later, the proclaiming of the Hungarian Soviet Republic under Bela Kun. These events, observed Hans Richter, “had stirred men’s minds, divided men’s interests and diverted energies in the direction of political change.”[37] According to historian Robert Levy, Tzara around this time associated with a group of Romanian communist students, almost certainly including Ana Pauker, who later became the Romanian Communist Party’s Foreign Minister and one of its most prominent and ruthless Jewish functionaries.[38] Tzara’s poems from the period are stridently communist in orientation and, influenced by Freud and Wilhelm Reich, depict extreme revolutionary violence as a healthy means of human expression.[39]

Among the other Jewish artists and intellectuals who joined Tzara in neutral Switzerland to escape involvement in the war were the painter and sculptor Marcel Janco (1895–1984), his brothers Jules and George, the painter and experimental film-maker Hans Richter (1888–1976), the essayist Walter Serner (1889–1942), and the painter and writer Arthur Segal (1875–1944). After Zurich, Dada was to take root in Berlin, Cologne, Hanover, New York and Paris, and each time it was Tzara who forged the links between these groups by organizing (despite the disruption of the war and its aftermath) exchanges of pictures, books and journals. In each of these cities, Dadaists “gathered to vent their rage and agitate for the annihilation of the old to make way for the new.”[40]

Go to:

Brenton Sanderson is the author of Battle Lines: Essays on Western Culture, Jewish Influence and Anti-Semitism, banned by Amazon, but available here.

[1] Menachem Wecker, “Eight Dada Jewish Artists,” The Jewish Press, August 30, 2006. http://www.jewishpress.com/printArticle.cfm?contentid=19293

[2] Bill Holdsworth, “Forgotten Jewish Dada-ists Get Their Due,” The Jewish Daily Forward, September 22, 2011. http://forward.com/articles/143160/#ixzz1ZRAUpOoX

[3] Wecker, “Eight Dada Jewish Artists,” op. cit.

[4] Amy Dempsey, Schools and Movements – An Encyclopaedic Guide to Modern Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 2002), 115.

[5] Robert Short, Dada and Surrealism (London: Laurence King Publishing, 1994), 7.

[6] Matthew Gale, Dada & Surrealism (London: Phaidon, 2004), 46.

[7] Wecker, “Eight Dada Jewish Artists,” op. cit.

[8] Leah Dickerman, “Introduction & Zurich,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada (Washington D.C., National Gallery of Art, 2005), 10.

[9] Andrei Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess (Princeton University Press, 2009), 209.

[10] Ibid., 173.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Gabriele Crepaldi, Modern Art 1900-1945 – The Age of the Avant-Gardes (London: HarperCollins, 2007), 194.

[13] Dickerman, “Introduction & Zurich,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 33.

[14] Alice Armstrong & Roger Cardinal, “Tzara, Tristan,” Justin Wintle (Ed.) Makers of Modern Culture (London: Routledge, 2002), 530.

[15] John Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 1981), 179.

[16] Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess, 213.

[17] Jerome Rothenberg in Norman Finkelstein, Not One of Them in Place and Jewish American Identity (New York: State University of New York Press, 2001), 100.

[18] Milly Heyd, “Tristan Tzara/Shmuel Rosenstock: The Hidden/Overt Jewish Agenda,” Washton-Long, Baigel & Heyd (Eds.) Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Anti-Semitism, Assimilation, Affirmation (Lebanon, NH: University Press of New England, 2010), 213.

[19] See Nicholas Zurbrugg et al. Critical Vices: The Myths of Postmodern Theory (Amsterdam: OPA, 2000).

[20] Codrescu, The Posthuman Dada Guide: tzara and lenin play chess, 212.

[21] Sarane Alexandrian, Surrealist (London: Thames & Hudson, 1970), 30-1.

[22] Russell, The Meanings of Modern Art, 182.

[23] Jeffrey T. Schnapp, Art of the Twentieth Century – 1900-1919 – The Avant-garde Movements (Italy, Skira, 2006), 392.

[24] Ibid., 389.

[25] Tony Godfrey, Conceptual Art (London: Phaidon, 1998) 41.

[26] Robert J. Wicks, Modern French Philosophy: From Existentialism to Postmodernism (Oxford: Oneworld, 2003), 10.

[27] Godfrey, Conceptual Art, 40.

[28] H. Harvard Arnason, A History of Modern Art (London: Thames & Hudson, 1986), 224.

[29] Dickerman, “Introduction & Zurich,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, 9.

[30] Schnapp, Art of the Twentieth Century – 1900-1919 – The Avant-garde Movements op cit., 396.

[31] Boime, “Dada’s Dark Secret,” Washton-Long, Baigel & Heyd (Eds.) Jewish Dimensions in Modern Visual Culture: Anti-Semitism, Assimilation, Affirmation, 98 & 95-6.

[32] Ibid., 96.

[33] Dickerman, “Introduction & Zurich,” Leah Dickerman (Ed.) Dada, op cit., 35.

[34] Hans Richter, Dada – Art and Anti-art, (London & New York: Thames & Hudson, 2004), 33.

[35] Gale, Dada & Surrealism, 80.

[36] Ibid., 56.

[37] Richter, Dada – Art and Anti-art, 80.

[38] Robert Levy, Ana Pauker: The Rise and Fall of a Jewish Communist (Berkley: University of California Press, 2001), 37.

[39] Philip Beitchman, I Am a Process with No Subject (Gainesville: University of Florida Press, 1988), 37-42.

[40] Dempsey, Styles, Schools and Movements – An Encylopaedic Guide to Modern Art, op cit., 115.

Speaking of “Jewish roots” (of Dada): That Jews have always endeavored to prevent White fertility with all manner of social engineering “inventiveness” is no accident. After all, it is about the root of all evil, “Amalek”, which they strive to eradicate (ausrotten). After all, they not only popularized the condom and turned it into a mass-produced and used item (Julius Fromm), but also the contraceptive pill (“birth control”), which alone prevented the birth of dozens if not hundreds of millions of whites (Djerassi, Pincus). It is not without reason that the biological term gene and the religious term genesis have the same “root”. The greatest success of the Jews is the prevention of any future White “generations”. https://nationalvanguard.org/2023/04/they-cant-just-kill-us-outright-or-can-they/

“Why does Mark Potok, senior fellow at the SPLC, keep a list on his wall of the non-hispanic white population by the decade?” https://i.redd.it/ymzeipty47e21.png

“Because the conclusion that Jew Potok follows closely – if not with joyful satisfaction – the steady decline of the white share of the world population is not just is a malicious right-wing extremist insinuation but also a typical anti-Semitic conspiracy theory, trope and canard for no reason! Shalom, after all, means PEACE (and rest in peace for the goyim). Only that alone makes perfect logical sense, end of debate and Mazel tov!”

‘It’s what we do now that counts.’

The Jew is always present and involved where it goes to the core, to the root. He considers himself to be endowed with the privilege of intervening in the genetics of the white man in order to trigger changes that correspond to his sick psyche.

In the very good 2005 German documentary “Frozen Angels,” Bill Handel boasts: “We Jews are God, we are allowed to do anything, and we do it!” Also present in the film is his tribal bro Cappy Rothman, “fertility pioneer” https://www.dailybreeze.com/2023/03/27/how-mobsters-son-dr-cappy-rothman-became-a-fertility-pioneer/

https://de.zxc.wiki/wiki/Frozen_Angels

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bill_Handel

P.S. It is also no coincidence that Jews of all people run all these gene institutes, by means of which mainly Americans let themselves certify their (alleged) descent.

Handel’s brother is a notorious pornographer with a terrible reputation for viciousness even amongst his fellow pornographers. He specializes in brutal gang rapes and sadism. Yes indeed, they are like gods.

Those who are actually fertile are condemned to childlessness, while Mr. Rothman takes pride in procreating the infertile, who are normally eliminated by nature from the stream of life.

“I couldn’t find anything on him being a Jew” https://dailystormer.in/american-medical-association-finally-gets-its-first-ever-faggot-president/

“Jesse ‘Menachem’ (!) Ehrenfeld”, Herr Anglin!

Is this a revision of the article published in November 2011, or simply a reprint?

it’s much expanded, with a lot of new material.

I recall the original, too. I’d forgotten that 2011 was the year of publication, however. Thank you for the reminder, and thanks to Kevin for the clarification.

Given that everything written by Brenton Sanderson is insightful and revealing, I look forward to reading the remaining parts.

Speaking of (Cabaret) Voltaire: The nut jobs of “Renefart” publish today a poem by him called “The Temple of Friendship”. https://i.ibb.co/rQVpjWr/renefart.jpg

https://www.poetry.com/poem/37864/the-temple-of-friendship

In principle, there is nothing wrong with friendship. But since Voltaire was a Freemason, the use of a phrase like “Temple of Friendship” may unmistakably be interpreted as a reference to Jewish infested Freemasonry. There is even a masonic lodge of the same name (jewgle “Freimaurer” & “Zum Tempel der Freundschaft”). A noble lady named Friederike Brun once wrote a poem with the same title (“Der Tempel der Freundschaft”), but this was perhaps more a reference to Greek antiquity.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Friederike_Brun

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Temple_of_Friendship

A few decades ago when I used to listen to NPR during the evening commute, I would hear Andrei Codrescu‘s commentary and think, what the hell is this guy trying to say? At the time, I didn’t know he was jewish (there was no “Early Life” to confirm) but I did imagine him as looking jewish.

I wonder if the current absurd Woke movement in America has the same roots.

If you mean are Jews behind it: yes, yes they are.

For some idealistic reason I believe that the only hope for AMERICA…is building a (new nation) LOCAL STATE RED MAGA Nationalists regional/block power. Since it is quite obvious that DEMs are pushing for a cold/low intensity proxy Civil War II to strungle destroy RED MAGA state power. Unfortunately the RED MAGA STATES…end up usually backing down on their core issues specially transgender child/schools sexual mutilations..why? The National Divorce is coming sooner or later, the best option is to prepare for it. RED MAGA must work to see a Multiracial coalition of RED MAGA STATES..,to build a regional block of states, to fight the DEM trans subversion/terrorism. Once the new red block of states gains power..then they could start proposing key/core issues for Americas future like BUILDING the WALL, immigration, schools, Manufacturing, ..articulate a REBIRTH of America…BREAK away from the failed BLUE DEM TRANS ANTIAMERICAN TYRANNY…achieving this objective will take courage, valor, a love for America without any apologies.

Tzara and his subversive movement Dadaism is just another example of what E Micheal Jones calls the Jewish revolutionary spirit. The Jews are in a constant state of rebellion against the natural law as proscribed by God. I am convinced that there is spiritual component to this conflict. The jew is the instrument of satanic evil on earth. Lies, manipulation, usury, sexual deviance, corruption warfare and hatred are demonic attributes exemplified in the Jew. We will not defeat them without reconnecting to traditional Christianity.

This is it. Words obscure it.

You’re exactly right. Traditional Catholicism, actual Catholicism, is the only bulwark against these creatures. There is a spiritual element. When Satan offered the kingdoms of this world to the Jews in return for their worship, as he did to Our Lord, the Jews said: where do we sign?

” We will not defeat them without reconnecting to traditional Christianity.”

Wishful thinking .

Traditional Christianity was unable to prevent a disconnection of worshippers . How would reconnecting to the same old program prevent another disconnection ?

Perhaps it is time to consider a new religion that is designed to oppose rather than accommodate internal subversion .

I had heard Evola was involved with Dada and I wondered what sense that made. So, he left it. OK.

For Menachem Wecker, the works of the Jewish Dadaists represented “not only the aesthetic responses of individuals opposed to the absurdity of war and fascism”

A convenient bit of anachronism. What fascism was there in in the early 1900s?

Rosenstock (aka, S. Sabyro, aka Tristan Tzara) himself was far more accurate: “Dada is using all its strength to establish the idiotic everywhere. Doing it deliberately. And is constantly tending towards idiocy itself.” Nevertheless he was not doing it justice: the idiocy had poison, namely visceral hatred for the Christian world, its culture and traditions they wished to destroy.

The “otherness” they complain was projected on them by the anti-semites was self-imposed wherever they lived or relocated. They carried their ‘eruv’ with them like a slug carries its house on its back, and only Jews and few dependable philosemitic gentiles were admitted in. In Romania he was close to the Iancu (styed ‘Janco’ in France) brothers, with the painter Victor Braun (who later painted “Christ in the Cabaret) and with cryptojew Ion Vinea. For a movement that promoted “exaggerated individualism” its promoters had an astounding agglutinative propensity.

His poetry was like Jackson Pollock’s “drip” paintings: an insult to Western art and cultural heritage. Not surprisingly, although not Jewish himself, Pollock was quickly recognized as useful. Clement Greenberg wrote: “I took one look at it and I thought, ‘Now that’s great art,’ and I knew Jackson was the greatest painter this country had produced.”

He got married to Jewess Lee Krasner and his work got a bar mtzva: “Art dealer John Bernard Myers once said “there would never have been a Jackson Pollock without a Lee Pollock”, whereas fellow painter Fritz Bultman referred to Pollock as Krasner’s “creation, her Frankenstein”, both men recognizing the immense influence Krasner had on Pollock’s career.”

Rosenstock had it made: he was a certified Jew.

As for:

1.”“Tristan Tzara” was the pseudonym he adopted in 1915 meaning “sad in my country” in French, German and Romanian.” I know of absolutely not a single syntagm that is the same in French, German and Romanian.

2. Codrescu says: “Sammy Rosenstock’s grandfather was the rabbi of the birthplace of many brilliant Jewish writers, including Paul Celan and Elie Weisel.”

Embarrassing for a Jew like Codrescu to ignore Elie Wisel’s birthplace: Sighet in Transylvania, not Chernowitz in Bukovina.

Today, “Juice” is scheduled to fly to Jupiter (provided

the Ariane does not suffer a false start). This spicy as-

troturfed Juice is an ESA venture that took 8 years to

develop, just as long as its travel time to the gas giant.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Jupiter_Icy_Moons_Explorer

https://www.nytimes.com/2023/04/13/science/juice-jupiter-launch-esa.html

After all, the James Webb of Lies telescope

has just delivered the latest captivating ima-

ges of the creative inventors’ steel-blue God.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mBLmEu9HzQ0

On Ganymed, five German Nazi astronauts had

already landed in a bell-shaped UFO in 1977, al-

beit only in the mind of director Rainer Erler.

Three of them (Frank, Prochnow, Friedrichsen)

should have actually gone to the Gemini mission,

because they are actually zodiac signs Gemini.

Mr. Gärtner as Aries missed the arrival on Mars

and Mr. Laser (the inventor of laser beams) is

the only one in the movie who goes totally crazy

because he as Aquarius didn’t get to Uranus.

https://de.zxc.wiki/wiki/Operation_Ganymed

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YWq1vPKQ83I

https://murray-lab.caltech.edu/CTX/V01/SceneView/MurrayLabCTXmosaic.html

Developed by the “Waffle SS” and assembled

in a “concentration camp” in the British Chan-

nel Islands by 6 million “Holocaust” survivors.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Die_Glocke_(conspiracy_theory)

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dieter_Laser

https://wat32.tv/search-movies/dieter%20laser.html

Laser in his favorite role as Dr. Mengele

in space (concentration camp as a flying

object), who chastises perverted Jews.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=H3Ap5_zG-7M

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ezXc1cArWj4

In “Führer Ex,” Laser played a woman killer

who shares a prison cell with a “neo-Nazi”.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/F%C3%BChrer_Ex

Apparently, an American Jew had

personally helped a lot to bring this

“GDR Nazi” back on the right track.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tom_Reiss

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lev_Nussimbaum

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hanns_Heinz_Ewers

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Wolfgang_von_Weisl

This is it. Words obscure it.

…” the absurdity of war “…

Is that notion why most Nordics/Whites do nothing to oppose and are complacent about the ILLuminati sponsored UN genocidal assault against them ?

It should be obvious that pacifism in response to genocide is just as or more absurd than making war against a mortal enemy ?