The Race for Space: Repulsive Racist Reflections on Awesome Astronautic Aspirations

Stars and butterflies — no good life is complete without them. But alas, modernity has been waging war on them both for many decades. Light pollution has bleached and blasted the night-sky, depriving countless millions of the beauty and astrobrontic awe that should have been their birthright.[1] At the same time, butterflies have been blasted and battered by industrial agriculture and construction, by those mechanical Jacobins known as cars and by the general trash and detritus of modernity.

Richness, color and detail

So should there be a Minister for Stars and Butterflies in any serious White Nationalist government, battling on their behalf against the bleaching, blasting and battering? No! I think that would be a very bad idea. As Peter Simple might have said: better to let stars fade from all sight and butterflies flutter into oblivion than draw them into the world of bureaucracy and politics. But there’s been a paradox at work. The same science-stained, techno-toxic modernity that has waged war on stars and butterflies has enabled us to understand them in ever greater depth and to see them with a richness, color and detail that would have astounded the generations that lived before photography.

Butterflies and Stars: two of my favorite books about two of my favorite things

Butterflies and Stars: two of my favorite books about two of my favorite things

And yet there are no photographs in two of my favorite books about these twin glories of Creation. The World of Butterflies (1988) by Valerio Sbordoni and Saviero Forestiero, originally published in Italian as Il Mondo delle Farfalle, is lavishly illustrated with paintings and drawings of butterflies, not with photographs. It’s a serious scientific text but it’s also a work of art. And there are no photographs in Giles Sparrow’s A History of the Universe in 21 Stars (2020). Or almost none — the few that do appear are far out-numbered by hand-drawn sketches of constellations and asterisms by the artist Laura Barnes.

Prehistoric pattern-recognition: the Nebra Sky Disc from Saxony-Anhalt, Germany (image from Wikipedia)

Prehistoric pattern-recognition: the Nebra Sky Disc from Saxony-Anhalt, Germany (image from Wikipedia)

By sketching the stars, she was stepping far back into prehistory and using the most important mental tool not just in art but in science too. Our first steps towards understanding the Heavens came by bringing them down to Earth: we saw patterns in the stars and likened them to animals and human figures, from Taurus the Bull to Orion the Hunter. Pattern-recognition is what powers both art and science, but modern science relies on the most abstract and yet powerful method of pattern-recognition — and pattern-processing — ever devised.

Mundane models

It’s called mathematics. Almost all the discoveries described in Sparrow’s book are based on it, directly or indirectly. Mankind has not yet reached the stars, but has built models of them here on Earth using math and managed to explain how they’re born, grow and die. Stellar death can be extraordinarily violent, as Sparrow describes when he looks at novae and supernovae. But stars can live violently too, particularly when they’re part of a binary system. And they can live for an extraordinarily long time: it’s mindboggling to think that red dwarfs could be “functionally immortal,” shining not for billions but for trillions of years (ch 9, “Proxima Centauri,” p 123). From red dwarfs to red giants, from famous flammifers like Betelgeuse, Sirius and Algol[2] to obscurer orbs like Helvetios, RS Ophiuchi and Eta Aquilae, this book is an excellent survey of a bewildering — and brain-expanding — variety of stars and their galactic settings.

But I couldn’t describe A History of the Universe as a work of art or as a serious scientific text. No, it’s a popular introduction to some of the awe-inspiring discoveries made in the ever-quickening field of astronomy. Many more discoveries have been made in the half-decade since its publication, but like most of those that Sparrow writes about, most of the new discoveries have rested on something that is weightless, odorless and soundless, impossible to touch, taste, smell or hear. But we can certainly see it. The French philosopher Auguste Comte (1798-1857) risibly asserted in 1835 that “both the chemical composition and temperature of stars would remain for ever unknowable.” (ch 3, p 32) That is, his assertion was risible in the literal light of what was to come, but seemed perfectly reasonable at the time. How could Comte have guessed at the glorious gifts that resided in simple starlight? We can’t reach the stars, we can’t sample and test the substances that combine and combust within them, but it turned out that we didn’t need to. What Comte asserted, Fraunhofer had already annulled:

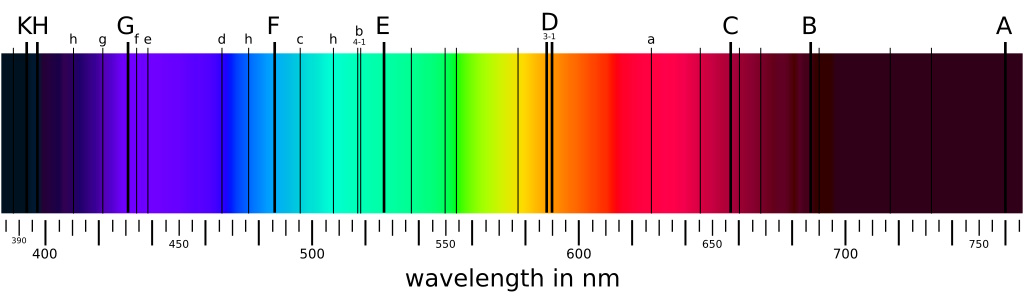

[An inventive German glassmaker called Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787-1826)] wanted to study the spectrum in detail, and realised that it wasn’t enough to just stick a prism into a broad beam of light as Newton had done — the dispersed colours from different parts of the beam overlapped each other and washed out detail. So, he narrowed down the beam by passing it through the narrowest possible slit, then sent it through a prism made from glass of his own secret recipe. He then studied the emerging beam through a telescope-like eyepiece that could pivot to see different parts of the refracted beam.

When Fraunhofer used this device (which we would today call a spectroscope) to study sunlight, he discovered that its rainbow-like “continuum” of colourful light was crossed by hundreds of narrow dark lines, varying in strength and intensity. This was weird — it suggested that the Sun either wasn’t producing very specific colours of light, or that these colours were somehow being prevented from reaching Earth. (ch 3, “Aldebaran,” p 31)

Voids in the visual — Fraunhofer lines (image from Wikipedia)

Voids in the visual — Fraunhofer lines (image from Wikipedia)

It was indeed weird. It was also wonderful, as would become apparent in time. Those voids in the visual wouldn’t be explained for another forty years. When they were explained, Comte’s assertion was annulled. It turned out that immaterial light could be barcoded by matter, whose elements absorbed or emitted photons at characteristic frequencies, leaving dark or bright lines in the spectra of stars and other astronomical objects. And that was how, by 1864, two English researchers could read the chemical composition of a giant red star called Aldebaran:

The pair identified 70 lines in the white, yellow, orange and red parts of the star’s spectrum. There were clearly many more towards the blue end, but here the background light grew so faint that it was impossible to pin them down. The measurable lines matched up to emissions from nine different elements — sodium, magnesium, hydrogen, calcium, iron, bismuth, tellurium, antimony and mercury. (ch. 3, “Aldebaran,” p. 34)

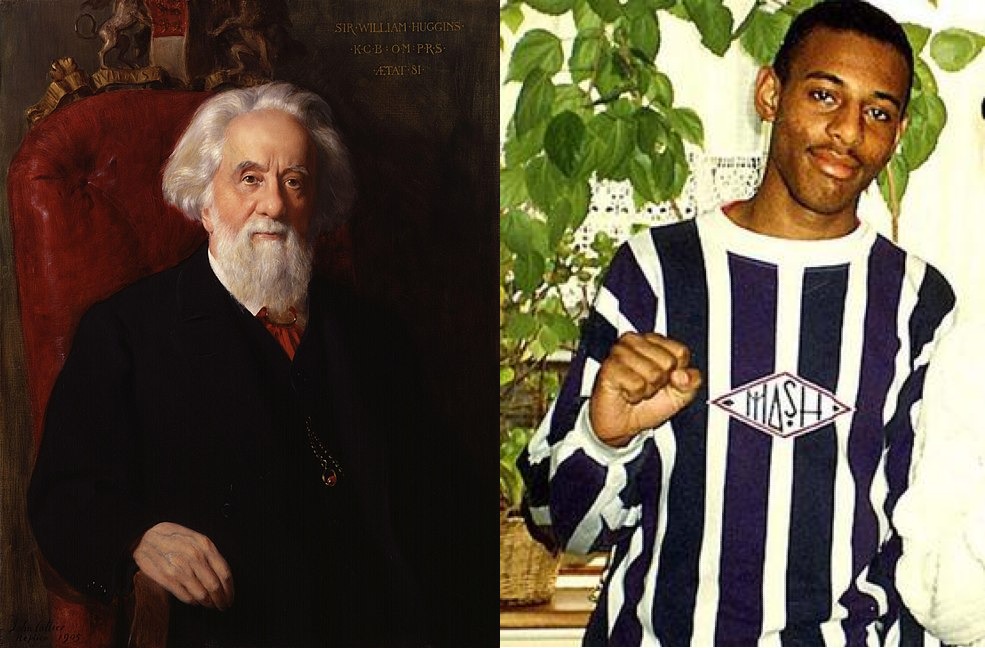

White achiever and Black martyr: William Huggins and Stephen Lawrence (images from Wikipedia)

White achiever and Black martyr: William Huggins and Stephen Lawrence (images from Wikipedia)

And who were those pair of pioneers? Not one in a hundred English schoolchildren could tell you nowadays. Not one in a thousand. And I mean genuine English schoolchildren — White ones belonging to the same race as that pioneering pair who pulled off that chemical coup. Appropriately enough, they were Bills who coup’d — William Huggins (1824–1910) and William Allen Miller (1817–70). But why are the names of those two White achievers and awe-inspirers far less known in modern England than the names of the two Blacks Stephen Lawrence and Rosa Parks?

The Pale Male Paradox

Well, that comes down to another barcode that was constantly in my mind as I read Sparrow’s book — the barcode of DNA. But the White writer Giles Sparrow himself will not have had DNA in mind as he wrote the book, just as the White writer Simon Winchester didn’t when he wrote a book called Exactly: How Precision Engineers Created the Modern World (2018). When I reviewed Exactly back in 2021, I described how it shed light on the Pale Male Paradox, namely, that White men achieve most and are vilified worst. Giles Sparrow’s book sheds light on the paradox too, because the great astronomical achievements he describes are overwhelmingly the work of stale pale males like Fraunhofer, Huggins and Miller. Some stale pale females come into the story too, but White women have never been essential to STEM — Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics — in the way that White men have been.

All that ultimately comes down to the barcode of human DNA, the helix of chemicals sculpted by evolution in subtly different but hugely significant ways as humans spread across the planet and entered new environments. Humans also created new environments for themselves: the invention of the bow relaxed selection for muscle and bulk; the invention of writing harshened selection for eyesight and intelligence. DNA explains both why human groups look different and why they behave different. And so it explains why some groups achieve so much and some so little. The Whites Huggins and Miller achieved the awe-inspiring; the Blacks Lawrence and Parks achieved the awe-undermining. Or rather, they were used to undermine the awe of White achievements by Jews, a group separated by their DNA from both Blacks and Whites.

Recognizing race isn’t good for Jews

Jews are another stale pale group that have been important in the story of modern astronomy and particularly of astrophysics. But they weren’t essential: like White women, they entered a field created by White men and the field would still have existed and flourished without their contributions. And although Jews have certainly made big contributions to STEM, they’ve also imposed big contractions on STEM. Jewish biologists like Stephen Jay Gould, Richard Lewontin, Leon Kamin, and Steven Rose have labored long and hard not to elucidate biological reality but to obscure and obfuscate it. They’ve denied the existence and importance of race, because recognizing race isn’t good for Jews. And that’s what governs Jewish ideas and ideology: not questions of truth or falsehood, but questions of advantage or disadvantage for Jews.

In other words, Jews are strongly ethnocentric, or centered on themselves. Whites, by contrast, are strongly exocentric, or centered outside themselves. Or White men are exocentric, at least. That’s why those two White men, William Huggins and William Allen Miller, devoted their energy and ingenuity to collecting and analyzing the faint light of distant stars, not to enriching themselves or advancing the cause of the White race or of humanity in general. After all, what Earthly use or practical importance is the chemical composition of Aldebaran? Well, there’s another paradox there: the highly impractical and abstract science of astronomy turns out to be central to the most practical question of all, that of survival for the entire human race. The stars and star-stuff fascinate some of us and should frighten all of us, because stars sometimes explode. And star-stuff sometimes falls from the sky.

Poisonous prophecy

An asteroid doomed the dinosaurs and sooner or later an asteroid might doom humanity too. If a solar hiccup or X-rays from a supernova or some other and yet unimagined disaster — literally a “bad star” — doesn’t get us first. The great White writer Arthur Conan Doyle, creator of Sherlock Holmes, raised the possibility of doom from the stars in a story published more than a century ago. His character Professor Challenger, who deserves some of the abundant fame still enjoyed by the detective, says this in one of Doyle’s typically inventive and far-sighted stories:

A third-rate sun, with its rag tag and bobtail of insignificant satellites, we float towards some unknown end, some squalid catastrophe which will overwhelm us at the ultimate confines of space, where we are swept over an etheric Niagara or dashed upon some unthinkable Labrador. [There are] many reasons why we should watch with a very close and interested attention every indication of change in those cosmic surroundings upon which our own ultimate fate may depend. (“The Poison Belt,” 1913)

Challenger was right. And would have been righter still if he’d said that watching wouldn’t be enough. We have to enter and permanently inhabit our “cosmic surroundings” to ensure our ultimate fate. Or at least postpone our demise. But which “we” will do that? That is, which human race will get off the Earth and establish permanent bases on the Moon and Mars, on the satellites of Jupiter and Saturn? Which race will begin the voyage to the stars? In short, which race is the race best-fitted for space? Giles Sparrow’s A History of the Universe in 21 Stars demonstrates that, in one sense, the race for space has been the White race. Modern astronomy has been created by stale pale males from Europe. They’ve gathered data by inventing and refining instruments like telescopes and spectroscopes,[3] then used that data to build mathematical models spanning vast stretches of space and time. Without those stale pale males — men like Isaac Newton, William Huggins and Fred Hoyle — it’s entirely possible that astronomy would have remained pre-modern, confined to classifying and cataloguing the stars, unable to study them in any detail or comb their light for clues of composition and cataclysm.

Awesome astronautic aspirations: this anti-Falun-Gong poster is cheesy, but China is serious about getting into space[4] (image from ChinesePosters.net)

Awesome astronautic aspirations: this anti-Falun-Gong poster is cheesy, but China is serious about getting into space[4] (image from ChinesePosters.net)

Stale pale males also brought astronautics — space travel — to fruition, building rockets and breaking Gaia’s gravitational embrace. But the promise of the Moon landings remains unfulfilled. Whites got there and walked there, but haven’t been back in over half-a-century. So who will be the race for space in future? Who will be the race that wins the race for space? And I think it will be a race that wins, that is, a distinct racial group, not the rainbow coalition imagined by another great White mind in a rare departure from realism:

I said a few years ago that I wanted Britain to advocate and start practical work with similarly minded players (e.g Bezos, Elon) on a permanent manned lunar base with whites, Chinese, Russians, Indians, blacks, Japanese etc all living up there building long discussed space infrastructure, a focus for humanity to think of us against the universe instead of us against each other. (“Q&A [Questions and Answers],” Dominic Cummings’ Substack, updated to August 2025)

Is Dominic Cummings serious when he proposes that Blacks should help staff a “lunar base” and build “space infrastructure” there? I hope he isn’t; I fear he is. If he is being serious, he’s also being ridiculous, not realistic. Let’s suppose that just the Chinese and Japanese tried cooperating on a project like that. Those two races could both supply intelligent, competent and psychologically stable teams for a lunar base. But I’d say the teams would find it very hard to succeed in tandem, working in the same base. As for a rainbow of races in a single base — that would reach ruin much more easily than success. And adding Blacks to the multi-racial mix? Well, the experiment of “Blacks in Bases” has been tried on Earth. The preliminary results have been exactly what any repulsive racist would expect:

Psychologists are in “constant” contact with a South African science team isolated for months at a base in Antarctica after physical assault and sexual harassment allegations were made, a government minister has said.

The environment minister, Dion George, whose department manages the country’s Antarctic programme, confirmed to the Guardian that psychologists and other experts were in “direct and constant” communication with the nine-member research team. […]

Dangers of life in close quarters on the three-module base, more than 2,600 miles south of Cape Town, were revealed last weekend with the publication of an email sent by a researcher accusing a male colleague of physical assault and making a death threat.

The person who made the allegations said they feared for their own and their colleagues’ safety, demanding “immediate action”, according to the South African Sunday Times newspaper, which published the email but removed the names.

“Regrettably, [his] behaviour has escalated to a point that is deeply disturbing. Specifically, he physically assaulted [name withheld], which is a grave violation of personal safety and workplace norms,” it said.

“Furthermore, he threatened to kill [name withheld], creating an environment of fear and intimidation. I remain deeply concerned about my own safety, constantly wondering if I might become the next victim.”

The letter said “numerous concerns” had been raised about the alleged attacker. (“Psychologists in touch with Antarctic base after assault allegation, South Africa confirms,” The Guardian, 19th March 2025)

Rainbow “research team” — the South African team roiled by criminality and chaos (image via Jared Taylor)

Rainbow “research team” — the South African team roiled by criminality and chaos (image via Jared Taylor)

I’m a repulsive racist and as soon as I read those basic details, I concluded that a simple principle could explain them: “Black Is Bountiful, Baby.” Black genetics and psychology create an abundance of crime and chaos wherever Blacks go. When I saw a photograph of the team in question, my conclusion was confirmed. The confident prediction of repulsive racists like me is that a Black was responsible for the criminality and chaos on that South African polar base. I’d say that an under-qualified Black was over-promoted onto the “research team” and made a typically Black contribution to its work. Why else would the newspaper have “removed the names”? Why else would the malefactor remain shrouded in mystery to this day? A Dindu dunnit, dammit. And I wouldn’t expect any different from Blacks on a lunar base. But I would expect worse. If you want murder on the Moon or rape in space, put Blacks up there. If you want success in space, there’s only one way to start it: with a team of carefully selected men — no women — sharing one racial heritage, one mother-tongue and one culture.

It was a team of White men for the first wave of Moon landings and it may be a team of Chinese men for the second. But Blacks? I think I can hear the Universe laughing. Yes, Blacks have been products of the Universe just as stars and butterflies have been, but that doesn’t give them equal value. If we reach the stars, I hope we take butterflies and not Blacks with us. But all three are products of the same universe and the same tool can be used to understand them: stars and butterflies on the one hand, Blacks on the other. The tool is called science and Giles Sparrow’s A History of the Universe in 21 Stars is an excellent guide to the power and pleasures of science. That’s why it abounds in stale pale males.

[1] If you take one thing from this essay, take the adjective “astrobrontic.” It comes from the ancient Greek ἀστροβρόντης, astrobrontēs, which means “thundering from the stars” and was used of the god Mithras.

[2] Arabic names like Betelgeuse and Algol are obvious examples of what modern astronomy owes to races living outside Europe, but it’s important to note that Arabic-speaking astronomers were not necessarily Arabs. As in mathematics, the Muslims who made important contributions to astronomy belonged to a single religion but not to a single race.

[3] Telescopes, spectroscopes and countless other scientific instruments depend on something in another favorite book that I hope to write about at TOO: The Glass Bathyscaphe. How Glass changed the World (2002) by Alan Macfarlane and Gerry Martin.

[4] The Chinese text on the poster, 崇尚科学,破除迷信, Chóngshàng kēxué, pòchú míxìn, means “Uphold science, eradicate superstition.”

All those photos and paintings of butterflies are nothing compared to seeing, and getting close to, the real ones in your garden. Sometimes, if you are lucky, one will sit on you. I don’t need to see photos of magnificent butterflies in South America or Africa; the ones here are just fine and I want them to continue with their life cycles right under my nose. Pictures are no substitute once they are gone compliments of the depredations of science, a god who didn’t know when to stop.

White Flight into space is absurd on its face…face meaning the laws of physics, space junk and cosmic radiation killing machines of human beings, etc.

Never mind economic realities, Jew-war as in right now and civil war/insurrection of niggers and even Mexicans as their beloved Mexico eclipses any attachments beyond free money to the USA. Ditto Europe and its darker cousins from the South and East. Europe is awakening to Race/LIberalism

Someone like Douglas Macgregor and his “50 million” aliens that must be removed from the US…is a great candidate for 2028 election.

Add depression into the mix and we have an explosive combination of factors… imminent.

Right now Trumpstein is equivocating on his various “finish the job” snarling rants on the Arabs and Persians. It is possible that someone like Macgregor/others are influencing the Emperor if for no other reasons than fear of the mid-terms trouncing Trump and his bellicose Jewish shit-eaters. The single fact of Trumpstein’s swollen ego and his obsession with winning may keep us alive for awhile….never mind the Palestinians whom Trump eats to satisfy the other zionist cannibals of Israel.

Getting back to Space Travel…it is a huge delusion, denoting a sickness with a normal existence on our planet with its beauties, immensity, and straits…from limits to death. Alienation from our Earthly life…Denial of limits, Refusal of Evolution’s demands and conditions….Pride, in one word.

Religion is gigantic delusion/narcisissism …that we demand of life the impossible, not content with our daily bread, work, family, friends and race.

Evolution is telling us Whites to kill our racial enemies. Kill or be killed. It is that simple. Evolution does not negotiate. Either/Or, Them or Us.

We got the Jewish Power on the run with Gaza -pilling of tens of millions of whites, especially young Whites. Give thanks to Palestine

“Someone like Douglas Macgregor and his “50 million” aliens that must be removed from the US…is a great candidate for 2028 election.”

MacGregor appears to believe Germans murdered 6 million jews with time release bug pullets in August when the temps were high enough to off gas with no heating source. Anyway, I don’t think he is this stupid so I am going with he is being paid as false opposition. Karen Kikotwatski too.