It is said that Jews of a certain vintage would pick up the New York Times at the breakfast table, back when it was consumed in its physical form, and ask “well, is it good for the Jews?”

What is picked up at this morning’s breakfast table — in paper or I-phone format — is most certainly not good for the Jews.

Just when the Jewish people were about to bask in the greatest outpouring of American sympathy since the 1967 war, an idiot named Bill Ackman has seized defeat from the jaws of victory, launching a vicious attack on a bunch of Harvard students for dissenting from the approved Israeli war narrative — a dissent that would probably have been ignored by most but for his attack.

As is well known by this point, early on Saturday, self proclaimed members of Hamas, numbering about 2–3,000, stormed across the (so we are told) lightly guarded border of Gaza into Israel, apparently killing or raping everything in sight, in addition to taking somewhere around 100 hostages, all with typical middle-eastern barbarity. While some stories, like that of the decapitated infants, are in dispute at this point, see Blumenthal, Source of dubious ‘beheaded babies’ claim is Israeli settler leader who incited riots to ‘wipe out’ Palestinian village – The Grayzone, enough appears to be confirmed that the methods — if not the strategic object — of the attacks have been condemned by most Western nations. In a word, this was far from a “surgical” strike at solely military targets with some inevitable, unfortunate, “collateral” civilian casualties like the strikes the US claims to enact. It was obviously aimed at creating civilian casualties.

These events of course represent a tragedy for the people involved even if, from a Jabotinskyite point of view, such events were and will remain inevitable so long as Palestinians ring the borders of Israel. But the silver lining for Israel and its Jewish supporters — if there can be one to such killings — was the huge outpouring of support for Israel from most Americans and most members of the Western block, most of whose knowledge of history terminates with last night’s CNN broadcast.

Of course, not all Americans bought the narrative. Students at a number of universities, including that university to whom all heads must bow — Harvard — have pointed out the historically irrefutable fact (as is the case in most wars) that there are two sides to the story. Some even expressed solidarity with the Palestinians and with Hamas, justifying their positions by equally horrific (though differently delivered) Israeli barbarity against Palestinians.

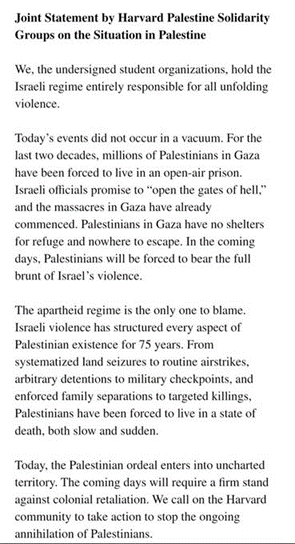

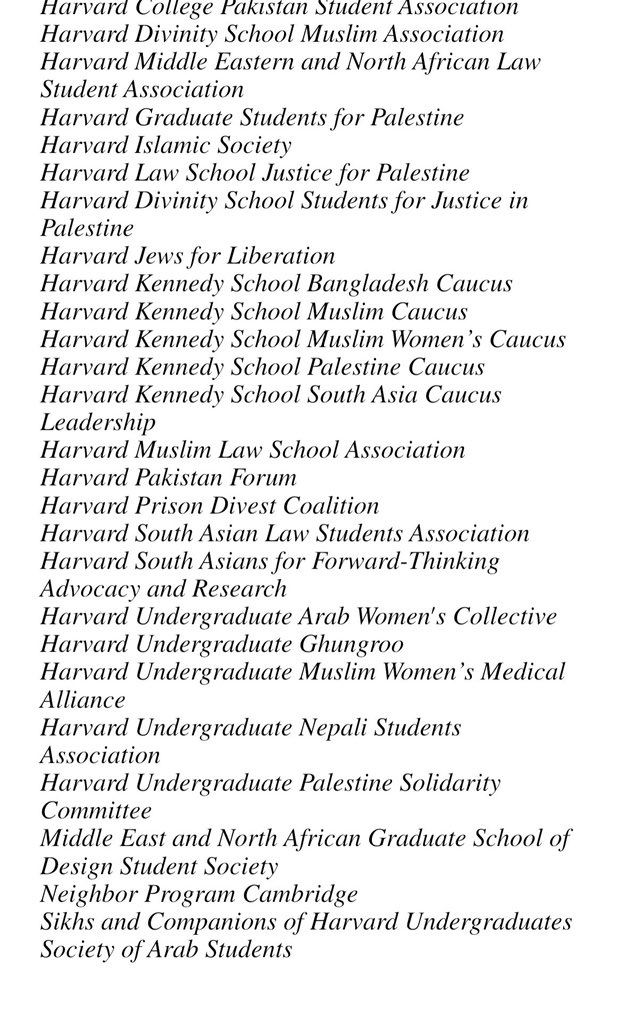

Although the Harvard groups’ letter has apparently been scrubbed from its original site on the internet, the following, taken from a purported copy on a Twitter (sorry, X) post, apparently represents a copy of the letter:

If this is the complete letter, frankly, it seems relatively anodyne. It expresses no rejoicing at the deaths nor even in the attack itself. It simply takes the point of view that the fault of this attack — and presumably all the violence of the last 75 years — is with Israelis, the people who evicted (or more accurately, were permitted by Britain and the US to evict) 700,000 Palestinians from their homes through massacres like Dar Yasein. Although most (though not all) Jews would disagree, the position certainly is a viable one based on the historic record. It also merely states what undoubtedly is (or is close to) the official position of the various groups representing the Palestinians. Even a number of (outlier and outcast) Jews, such as Max Blumenthal of Greyzone appear to agree with this analysis, and, in fact, add an edge totally absent from the Harvard statement.

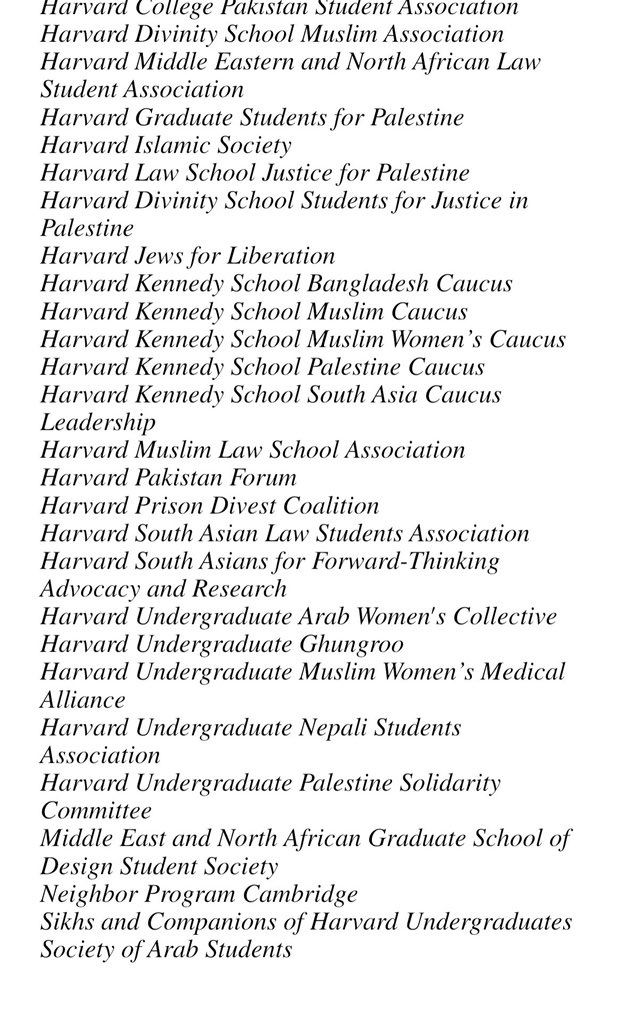

It should be noted that one of the organizations that signed the letter, at least according to the above partial reprint re-posted on Twitter, lists the “Harvard Jews for Liberation,” an apparently Jewish group, composed of persons who will undoubtedly be labeled self-hating Jews. The letter is certainly more restrained than the bloodthirsty statements by scores of “pro-Israel” commentators, including the Israeli defense minister who labeled the Gazans “human beasts” and who pledged to make the whole Gazan people — more than 2 million — accountable for last Saturday’s atrocities; or former member of the Knesset Michael Ben Ari, who states “There are no innocents in Gaza. Mow them down. Kill the Gazans without thought or mercy”; or Rabbi Yisrael Ariel, the Chief Rabbi of the evacuated Sinai Penninsula settlement of Yamit, waxing Biblical in September 2015: “If the Muslims and the Christians say from now on no more Christianity and no more Islam … then they would be allowed to live. If not, you kill all of their males by sword. You leave only the women.” All quoted at Information Clearing House.

Wow! No those are “no holds barred” statements. Not like the cucky, weakling, soy-boy Harvard “pro-Palestinians”! Where the hell was Bill Ackman when those statements were made and did he, for example, propose that Congress bar the entry of followers of such people into the United States or warn Wall Street firms not to interview them? Ho, ho, ho.

In fact, a member of the EU Parliament, Clare Daley, made the same point as the Harvard folks to the head of the EU in a response tweet.

Similarly, such former government officials as Ray McGovern, a CIA analyst who was the Presidential briefer for Reagan and Bush I, analyzes the situation much as does the infamous Harvard letter. “Can you give a brief synopsis of what’s happening in Israel?”; also talking on the “Israel as ally” issue at the National Press Club. Ray McGovern – Does Israel act like a U.S. ally? – YouTube .

The Jewish Norman Finklestein asked two days ago “What were they [the Gazans] supposed to do?”. He also agrees with the narrative set forth in the Harvard letter. The Palestinians Had NO OTHER OPTIONS — Norman Finkelstein – YouTube

To top it off, there are now reports that Israel was warned by Egypt 3 days before the attack and apparently chose to ignore the warnings. On purpose? Rachel Blevins on X: “How did Israeli intelligence miss that Hamas was planning such a massive attack? Well, it appears they didn’t. Reports are now revealing that Egypt repeatedly warned Israel of an attack coming from Gaza, but Israeli officials chose to ignore it and focus on their settlements in the West Bank instead. Also: Simon Ateba on X: “BREAKING: US confirms Egypt warned Israel ‘three days’ before Hamas attack. “We know that Egypt had warned the Israelis three days prior that an event like this could happen.”

Why? To create an excuse for a Jewish jihad into Gaza? This in addition to the fact that most experienced observers believe Israel — and Netenyahu himself — in the beginning helped promote Hamas to counter the then powerful Palestinian Fatah organization. Ron Paul: Hamas was created by Israel and the US to counteract Yasser Arafat… – Revolver News.

One thing for sure — we will never know. And if Ackman has his way, we will not be allowed to talk about any of these things either.

So, had the Harvard chicklings been better informed, and had they wanted to be truly nasty, they could have accused Netanyahu of working covertly with Hamas to create an horrific false flag attack justifying the taking of Gaza and its valuable gas fields. My God, what if they had said that!!

In any case, given that America thinks of itself as a free country with freedom of speech and given that Israel, after all, is not technically an “ally” of the U.S. — the U.S. has never entered into a formal security agreement with Israel such as it has through NATO with the European countries — Americans should be free without consequence to air their views on this difficult and complex subject, free from extortion, whether privately or publicly enforced, on any topic, particularly on Israel.

However, this is definitely not the case for Bill Ackman and a group of like-minded “CEO’s”.

Ackman, a Jewish hedge fund manager, has publicly demanded, on behalf of himself and a number of “CEOs” that he did not initially name, that Harvard release the names of the Harvard students behind the letter quoted above It appears that among the “CEO’s” Ackman is Abe Renick, the Jewish CEO of rental housing management startup Belong. In addition a number of other CEOs have followed suit, including Jonathan Newman, CEO of salad chain Sweetgreen (Newman is married to billionaire heiress Leora Kadisha who is a member of the Nazarian Clan, which is one of the world’s wealthiest Jewish Iranian families; she is the middle daughter of business tycoon Neil Kadisha and Dora Nazarian). Also: David Duel, CEO of health care services firm EasyHealth (David Duel is Jewish and “passionate” about giving back to the Jewish community), Hu Montegu, the CEO of construction company Diligent, Michael McQuaid, the head of decentralized finance operations at blockchain firm Bloq, Art Levy (presumably Jewish), head of strategy at payments platform Brex; Jake Wurzak, the CEO of hospitality group Dovehill Capital Management, and Michael Broukhim, apparently an Iranian Jew now a US citizen.A good number of these appear to be relatively small companies — perhaps a reason Ackman kept the names to himself initially.

And, as if on cue, we have Israel patriot Alan Dershowitz, former professor at the Harvard Law School (formerly the “Dane Law School” at Harvard, named for Nathan Dane, a donor who rescued the Law School in the early nineteenth century; he is long since forgotten, like most of Harvard’s non-Jewish donors). Dershowitz echoed Ackman, saying that students that “support murder and rape” should not be allowed to remain anonymous Students in groups that support rape, murder and Hamas should be named – YouTube No mention was made by Dershowitz of the many, many Jewish Harvard students that have over the years expressed support for Israel and implicitly its air strikes, use of phosphorous bombs, destruction of Palestinian homes, and use of collective punishment. Presumably, they’re all Goldman Sachs’ priority hires!

And today we read that a “big law” law firm named Winston & Strawn has just withdrawn an offer of employment to a Black NYU student, Ryna Workman, because of her tweet supporting the rights of the Palestinians. She was targeted specifically by Alan Dershowitz. See: Students in groups that support rape, murder and Hamas should be named – YouTube . The totality (apparently) of Workman’s tweet simply echoes the Harvard statement:

“I want to express, first and foremost, my unwavering and absolute solidarity with Palestinians in their resistance against oppression towards liberation and self-determination. Israel bears full responsibility for this tremendous loss of life. This regime of state-sanctioned violence created the conditions that made resistance necessary.”

Note that she references the “tremendous loss of life.” At least in this clip she does not, contra Dershowitz, “support rape [and] murder,” although, if one interprets Dershowitz to say that all Palestinians commit murder and rape (an astonishing charge which could be used to justify the genocide of the Palestinian people), then, perhaps. In fact, she appears, if anything, to decry the “tremendous loss of life.” What she says is that Israel’s policies are responsible. Dershowitz’s problem with her is obviously not that she supports murder, but that she holds the “wrong” party responsible.

Ryna Workman is now unemployed because of a nasty, vindictive Jewish supremacist law professor who is a fixture on conservative media in the US. She should talk to Norman Finkelstein, who was also pursued by the good professor for Norman’s apostasy on Israel, as well as his accusations that Dershowitz was guilty of plagiarism. Or ask Sue Berlach, Alan’s first wife, whom he left in the mid 1970’s for an affair with a young law aide, thereafter using his legal skills to get custody of her kids. She later simplified his life by committing suicide, jumping off the Brooklyn Bridge into the unforgiving waters of the East River 119 feet below. Dershowitz 1st Wife — Tragic Abuse, Divorce, Suicide) ; see also 5 Surprising Details From That New Yorker Alan Dershowitz Profile (forbes.com). So I guess Ryna can’t talk to Alan’s first wife after all, unless she’s a psychic medium and a really good swimmer to boot.

So, from Jews to Blacks: if you have an independent opinion on world affairs, fuck you. So much for the “Black-Jewish alliance”!

More recently, Ackman is reported to have doubled down on his demand, as follows:

“If you were managing a business, would you hire someone who blamed the despicable violent acts of a terrorist group on the victims? I don’t think so,” Ackman wrote. “Would you hire someone who was a member of a school club who issued a statement blaming lynchings by the KKK on their victims? I don’t think so. It is not harassment to seek to understand the character of the candidates that you are considering for employment.” Quoted at: Bill Ackman: It’s Not Harassment to Name Pro-Hamas Harvard Students (businessinsider.com)

The arrogant implication, of course, is that anyone who disagrees with the Israeli and Jewish opinion on this is of “low” character. But I guess that is what you get in a nation that now appears to operate on the principal, as E. Michael Jones would say, that truth is the opinion of the powerful.

It is worth noting that American statesmen like George Marshall (U.S. Secretary of State under Truman), the distinguished U.S. diplomat Loy W. Henderson, Ambassador to both India and Iran and Director of the State Department’s Office of Near Eastern Affairs under Roosevelt and Truman, and George Ball, Undersecretary of State under President Johnson, along with scores of other distinguished Americans, have been smeared with the “anti-Semite” label for raising significant questions about Israel’s activities — not to mention the propriety of its very creation; men who would undoubtedly have views not inconsistent with the letter issued by the Harvard students, having predicted 75 years ago events such as those just occurring. So, apparently, they would also be judged by the Jewish establishment today to have such “low character” as to be unemployable. The only Jewish pushback this author has seen is former president of Harvard, Larry Summers. Former Harvard president Larry Summers thinks Bill Ackman asking for lists of student names is the ‘stuff of Joe McCarthy])

It should be noted that a few radicalized Harvard students are not the only ones in the gunsights of these Jewish gangsters.

The Presbyterian Church of the United States has unequivocally endorsed boycotting and disinvesting from Israel and its products, as has the United Church of Christ, the Methodist Church, and the Quakers. The World Council of Churches has also called for divestment from Israel. Other Churches that have at least partially divested include the Alliance of Baptists, Church of the United Brethren in Christ, Mennonite Church USA, Roman Catholic Church, Unitarian Universalist Association, as well as the World Communion of Reformed Churches (a confederation that overlaps some of the above). Oy Vey, that’s a lot of Churches, bro. And the Jews thought the Catholic Church was their only enemy!!! Oops!!

Presumably congregants of these Churches will soon also make Ackman’s “unemployables” list for implicitly “blaming the victims”.

Student opponents of BDS certainly are on a very similar list, such as the list displayed on the so called “Canary Mission website, reputedly financed by Adam Millstein, another Jewish supremacist centimillionaire.

So will we soon come to a point where no member of the Presbyterian Church, the Congregational Church, or the Quakers — the denominations of most of the founding fathers including Thomas Jefferson, draftsman of the Declaration of Independence and James Madison, a principal architect of the Bill of Rights (Presbyterians) or John Adams or Roger Sherman (Congregationalist) — can ever again be offered a job on Wall Street or, perhaps, by a Fortune 500 company? Holy shit! We all better learn the “Hatikva” and throw that old musty painting of the signing of the Declaration in the waste bin if we want to earn a living in the America to come!

But at this point, it is worth noting whom these people pick on. Not on Max Blumenthal, who would just tell them to “go fuck themselves”. Not to Ray McGovern, who would just shake his head and smile “what’s new?” Not to Norman Finklestein, who would intellectually eviscerate them. Apparently Ackman is too scared even to take on the Harvard administration — adults. No, Ackman picks on soft targets, college kids, who, with some justification will believe their careers, and perhaps lives, are ending before they have begun. In a word, Ackman doesn’t dare pick on the strong. He picks on the weak. He is a cheap bully. The lowest form of scum.

And, we must ask, have we come to the point where, to get a degree from Harvard, to get a job, to keep a job, you need to kiss Jewish ass from morning until night?

The blunt fact is that Wall Street, the media, the universities, and the government are all now run by Jewish supremacists. In fact, it appears that, if the Jews get enough power, they will do to us in the U.S. exactly what they are doing in their other occupied territory to the Palestinians. Or as they did in the early decades of the Soviet Union. Ackman’s attack is just the start. Before the phosphorous bombs start raining down on our heads, if Ackman’s attitude is indicative of how Jews behave when acquiring positions of enormous power — and it clearly seems to be — perhaps we should ensure, au contraire, that a certain group should be barred from holding certain jobs, just as Ackman is proposing for people who disagree with his views on Israel. And that group is not comprised of the signatories to that Harvard letter, or George Marshall, or Loy Henderson, or George Ball.

Here’s some analogous proposals:

If this is how Jews use their power, how about barring them from any job in financial services?

How about barring Jews from holding any position as an officer or director in a publicly traded company?

How about barring Jews from holding any position of authority at any level of federal, state, or local government?

How about barring Jews from owning or operating any media assets?

How about barring Jews from voting, making campaign contributions, serving on juries?

How about offering physical protection to Jews but also preventing Jewish influence on the greater society?

Given the current viciousness of the Jews currently in power — Ackman, Schumer, Garland, are only the most prominent examples — would it be too much to ask for a Constitutional amendment depriving Jews of citizenship, replacing the passports they appear to disdain with residency certificates, revocable at will and requiring that the Jewish nation (both in and out of Israel) be represented by ambassadors rather than lobbyists, political fundraisers, and political hacks?

How would Bill Ackman like that? Maybe then he could actually go to Israel and sign up with the IDF. Then he could defend his true country — not the one of which he is a fake citizen, but his real one — Israel.

The proposal to bar Jews from financial service jobs is not so far-fetched as one might assume. In fact, a while ago, a number of Jews were indeed expelled from their chosen marketplace:

And Jesus went into the temple of God, and cast out all them that sold and bought in the temple, and overthrew the tables of the moneychangers, and the seats of them that sold doves, [13] And said unto them, It is written, My house shall be called the house of prayer; but ye have made it a den of thieves. Matthew 21:12–13

Perhaps the man that kicked them out remembered his earlier words:

Ye are of your father the devil, and the lusts of your father ye will do. He was a murderer from the beginning, and abode not in the truth, because there is no truth in him. When he speaketh a lie, he speaketh of his own: for he is a liar, and the father of it. John 8:44

Maybe our Lord and Saviour knew more than we think he did. Maybe He was actually pretty smart. Maybe we ought to listen to Him.

Thank you Bill Ackman, et. al. for reminding us — through your vicious, uncalled-for, activities — of that fact.

__________________________

1. The Jewish Revolutionary Spirit (Fidelity Press), by E. Michael Jones.