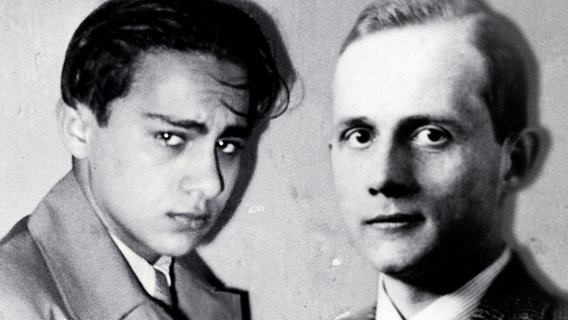

With today’s centennial of the death by lynching of Leo Max Frank, public attention has been fixed once again on the remarkable dual murders of Mary Phagan and Leo Frank. As is fairly well-known at this point, 13-year-old Mary Phagan was murdered in the National Pencil Factory in Atlanta on April 26, 1913. Leo Frank, her boss and last person to admit seeing her alive, was convicted of the murder.

His appeals went up to the Supreme Court of the United States and his conviction upheld at every level. Frank’s appeals to the administrative agencies of the State of Georgia also brought no change. Only when Governor John Slaton, a law partner of the Frank defense team, commuted the sentence to life imprisonment was Frank’s life apparently spared. But the outrage felt in Georgia over the impropriety of the Governor pardoning a client of his own law firm on his last day in office (and widely suspected of being bribed) resulted in a band of leading Marietta men planning and executing a daring break-in at the State Prison in Milledgeville, abducting Frank and driving over the primitive dirt roads of Georgia all night to hang him in Marietta at sunrise the next day.

The astonishing murder of Leo Frank has tended to soften the public’s view of his guilt in the murder of Mary Phagan.

Was Frank guilty of the murder of Mary Phagan?

His own subsequent murder is not material in establishing his innocence in the matter. It represents what might be called the “Ox-Bow Incident” mentality. We so dislike vigilante justice that we have a tendency to give the benefit of the doubt to the victims of such lynchings. Even in a case like this where Frank’s guilt was upheld at every level of the appellate legal system we recognize his subsequent murder as an assault on the entire legal system.

Francis X. Busch, a renowned trial attorney of a half century ago, pointed out one of the most powerful pieces of evidence against Leo Frank. “As has been argued in support of the jury’s verdict, that in the passage of nearly forty years since Frank’s brutal execution, not a single additional fact pointing to his innocence has come to light.”1

The Phagan family conducted a full and complete interview in 1934 with Jim Conley, the star witness of the State against Leo Frank. Conley was also the man the Frank defenders settled on as the most likely murderer instead of Leo Frank. The Phagan relatives’ interview with Conley convinced them that Conley was telling the truth about Mary’s murder. Mary Phagan Kean wrote “[t]here is no way my father would have let Jim Conley live if he believed that he had murdered little Mary.”2

Thus it came as something of a shock to the general public that in 1982 newspaper attention suddenly focused on the elderly Alonzo Mann. Mr. Mann was about the same age as Mary Phagan at the time of her death and had testified as a defense witness for Frank in his capacity as Frank’s office boy at the murder trial. Now Mann emerged from the shadows with the startling revelation that he had actually seen Conley carrying the apparently lifeless body of Mary Phagan down the front staircase when he re-entered the Pencil Factory on April 26, 1913. Jerry Thompson,3 Nashville Tennessean veteran reporter and anti-Klan investigator, worked up Mann’s story and brought before the public.

Mann was given lie detector tests and passed them. “Lie detectors” are not admissible in court in Georgia — unless all parties agree. They are of limited effectiveness because pathological liars and the very best of con artists often pass while persons of a more nervous disposition fail — even when the latter are telling the truth.

The Georgia Courts have mocked “lie detector” tests as follows:

There is simply no “lie detector,” machine or human. The first recorded lie detector test was in ancient India where a suspect was required to enter a darkened room and touch the tail of a donkey. If the donkey brayed when his tail was touched the suspect was declared guilty, otherwise he was released. Modern science has substituted a metal electronic box for the donkey but the results remain just as haphazard and inconclusive.4

On the national level the United States Supreme Court ruled in 1998 in United States v. Scheffer,5 that courts could bar the admission of the results of polygraph examinations in all cases without violating an accused’s constitutional rights. The Court did so because it noted that there is no consensus in the scientific community on the reliability of the “lie detector.” In short, the highest court in the land holds the “lie detector” to be “junk science.”

Mann’s ability to pass such a questionable test at best implies that he either completely believed his story or was an excellent story teller.

The Nashville Tennessean article was a tremendous hit; it was nominated for a Pulitzer Prize and picked up by newspapers all over the nation. On television and radio programs commentators gleefully announced that Mann’s testimony erased all doubts — baseless though they might have been — that Frank was actually innocent of the murder of Mary Phagan. As the Tennessean’s headline for the special supplement of March 7, 1982 shouted: “AN INNOCENT MAN WAS LYNCHED.” Books, docudramas and prizes for investigative journalism rained down on the heads of the crusading scribblers.6

Mann’s story was significant in that it directly contradicted Conley’s testimony of how Conley got the body of Mary Phagan to the basement of the factory after the killing. As the reader may recall, Conley was definitive in his testimony that he used the elevator to transport the corpse. The elevator had always interested the Frank partisans and Mann emerged as the last living witness to the case to discuss this exact issue.

The affidavit executed by Mann may be summarized as follows:

He was called as a witness for Frank, but he did not then reveal to any lawyer about his knowledge contained in the affidavit. Now, he was coming forward after the lapse of seventy years. “I want the public to understand that Leo Frank did not kill Mary Phagan.” He blamed his parents, his speech impediment and his fear of the crowds outside the trial “yelling things like ‘Kill the Jew!’” for his reluctance to speak up. Mann stated he was too young at the tender age of 14 to have realized that if he told what he saw that Frank would have been found innocent.

Here is what Mann claimed he saw the day Mary Phagan died. When Mann arrived at the factory at 8:00 a.m, Conley was seated under the stairwell of the first floor of the Pencil Factory. Conley had already consumed a lot of beer. Mann ignored Conley’s request for money and went up the stairway to assume his duties as Frank’s office boy. Frank arrived shortly afterwards. Mann worked till before noon when Frank permitted him to leave to join his mother for the Confederate Memorial Day parade. Mann promised Frank he would return after the parade and Frank allowed that he would probably still be at the Pencil Factory.

Leaving shortly before noon, Mann had not seen Mary Phagan come to collect her pay. Conley was still lounging in the stairwell when Mann left the factory. Mann did not pinpoint his departure time. He states he could have left between 11:30 or 11:45.

He stated “[I]t could not have been more [emphasis added] than a half hour before I got back to the pencil factory.” In other words, Mann returned somewhere between 12:00 and 12:15 based on his statement. Mann entered by the front door again, and looking to his right, saw Conley with Mary Phagan’s limp body (although he didn’t know Mary’s name at the time) standing between a trap door that led to the basement and the elevator shaft. He observed no blood or wound on the body of this limp, short white girl dressed in “pretty, clean clothes.” Mann was of the impression that Conley was about to dump the body down the trapdoor. He could not recall if the elevator was on the first floor; if it was not, then the shaft would have been open as well. “…[I]n a voice that was low but threatening and frightening to me he [Conley] said: ‘If you ever mention this I’ll kill you.’”

Mann started up the stairs to the second floor. He thought he heard movements up there, but thought better of it, turned and fled out the front door. Conley reached out for him, but Mann “raced away from the building.” Arriving at home, he told his mother — whom he was to have met at the parade — what he had seen. She immediately advised him never to tell a soul. “She told me that I was never, never to tell anybody else what I had seen that day at the factory. She said that she didn’t want me involved, or the family involved, in any way. She told me to go on about my business as if nothing had happened and that sometime soon I would have to quit working there. From then on, whenever I was at work, I steered clear of Jim Conley. I kept away from him and he did the same.”

“When my father came home my mother explained to him what I had seen and what Conley had said to me. My father told me to forget it and never mention it.”

Later, when questioned by detectives, Mann never told them about his return to the Pencil Factory building. At Leo Frank’s trial, while testifying as a witness for Frank, Mann only answered the questions he was asked. He following the advice of his mother and father and did not volunteer any further information. Mann offered his opinion that Conley was after Mary’s pay; he was not planning a sexual assault.

“Many times I have thought since all this occurred almost seventy years ago that if I had hollered or yelled for help when I ran into Conley with the girl in his arms that day I might have saved her life. I might have. On the other hand, I might have lost my own life. If I had told what I saw that day I might saved Leo Frank’s life. I didn’t realize it at the time. I was too young to understand.”

Family members continued to tell Mann not to tell anyone his story for years afterwards. An Atlanta newspaperman unnamed by Mann (but said by others to have been Ralph McGill, another crusading, Pulitzer Prize-winning liberal journalist) was disinterested in his story.

Mann also contradicted the testimony of the female factory employees who accused Frank of bringing women into the factory for immoral purposes. Mann never witnessed any such conduct.7 (Mann did not mention that he began working for Frank on April 1, 1913 so he had only been at the factory for twenty-six days at the time of murder.)

The Mann affidavit reopened the drive of the Jewish community for a “posthumous pardon” for Leo Frank. At a press conference at the Atlanta Jewish Community Center on April 1, 1982, the drumbeat began again. Jerry Thompson, at the press conference, was asked about the Phagan family’s reactions to all this information. “Jerry Thompson stated that some Phagan family members upheld their belief in the convicted Leo Frank’s guilt while others ‘were trying to be objective.’”8 “Sherry Frank (no relation to Leo Frank), area director of the American Jewish Committee, said Jewish leaders would like to make a possible exoneration of Frank an issue in the gubernatorial race this year.”9

Alonzo Mann, possibly because of his age and infirm heart, refused to respond to any questions except through his handlers at the Nashville Tennessean. This author contacted the Tennessean and was so informed at the time the news broke. Mary Phagan Kean was given the same answer, but because of her family connections she was finally able to meet Mr. Mann and form some impressions about him. She thought him “a fine gentleman; he believed what he had seen to be evidence of the truth.”10

Since Mann was never subjected to any cross-examination nor, evidently, even tough questioning about these matters, we are left with three possibilities concerning the worth of his testimony on an historical basis. It has long been held in Anglo-Saxon law that trial by affidavit is worthless and the cross-examination of a witness is essential to establish the truth or falsity of a proposition. So while Alonzo Mann’s affidavit is valueless from a legal standpoint, it does have historical significance and must be so analyzed as we find it.

Mann’s recollections could be (1) completely accurate and factual; or (2) weakened by seventy years of guilt and blurred memories, but basically accurate; or (3) a complete fabrication drawn up either by himself or with the assistance of other parties for a number of plausible reasons.11

Since Mann cannot be examined, having answered to the highest tribunal on March 19, 1985, let us look more closely at the statement itself.

First of all, Mann states that mobs were shouting things like “Kill the Jew” outside the trial. The most careful writers on the subject all agree that this is an urban myth with no basis in fact. Steve Oney, the most recent author on the subject, points out that there is no contemporary evidence for such a statement.12 Governor Slaton in his commutation order denied that Frank had been tried by a mob. But, like the typical urban myth, the legend persists. It is probably propelled by later events after the Slaton commutation and the assault of the “Knights of Mary Phagan” on the State Prison in Milledgeville.

In the statement Mann put himself as leaving the factory between 11:30 and 11:45. In his trial testimony, as recorded in the brief of evidence, Mann testified twice that he departed at 11:30.13 Since his testimony was given closer in time to the event in issue, we may presume that at least he was inaccurate in the later affidavit as to the time of his departure unless he was fudging on that topic when testifying for Frank at trial. So Mann’s affidavit is clearly at variance in this important matter with his own trial testimony given relatively shortly after the event. Given the heavy emphasis the defense attached to the timing of the assault on Mary, this is significant to say the least. It would seem highly unlikely that the skilled interrogation by Frank’s attorneys failed to unearth the later departure time (to say nothing of Mann’s return to the factory) given their theory of the case turned on the time element so heavily.

It is also noteworthy because of the importance attached to the timing of the arrival of Mary at the Pencil Factory. The defense made much of the testimony of streetcar operators that Mary could not have possibly arrived at the factory prior to 12:12 p.m. Although Dorsey seriously damaged this theory in his cross-examination, the defense steadfastly held to this narrative. If Mann’s recollections are correct, then pressing his affidavit times to the furthest, most favorable limit for Frank, the latest Mann could arrive back at the factory on the fatal day is 12:15 p.m. Under Mann’s time constraints, Mary had to be able to ascend the staircase, obtain her pay envelope from Frank, ask about work on Monday and descend the staircase, be attacked by Conley either upstairs or downstairs (without Frank hearing any struggle or screams in the otherwise quiet factory, as it was a holiday) be lifted up and carried by Conley to the point where he was seen by Mann next to the “hole” and elevator shaft. All this had to occur within an absolute maximum of three minutes. If Mann’s statement that he was away from the factory for not more than one-half hour is true, then in order to get Mary to the factory after Monteen Stover testified she arrived, Mann’s departure time had to change.

Stover’s unimpeached testimony is that she was in Frank’s outer office from 12:05 until 12:10 by the clock on the wall in the office. Frank was absent from his office and not a sound was heard by Stover. Consequently, the defense always asserted that Mary arrived two minutes after Monteen left — just enough time for the two of them to miss each other on the staircase and the street outside the factory. If Mann was gone for no more than thirty minutes, then his departure time must be shifted forward from his trial testimony or else he returns before Mary, by Frank’s testimony and the elaborate defense calculations, could have even arrived at the factory. No Frank defender has offered any explanation for the new time problems created for the defense by Mann’s affidavit.

Consider the plausibility of the affidavit statements concerning the response of Mann’s parents to the news that their son had witnessed what was doubtless the most sensational murder of their lifetimes. Conley returned to work on Monday, April 28th after the murder. Mann evidently returned to work as well according to his affidavit. Conley would continue to report to work until his arrest on May 1.

Can we believe that a fourteen year old lad would report to work alongside a black man who he had every reason to believe had committed the murder of Mary Phagan? Mann would have permitted an innocent man, the black night watchman Newt Lee, to languish in the jail while the sweeper Jim Conley, whom he feared — now with better reason than ever before — looked malignantly at him each day. Is that believable — even in present day America?

Gentle reader, life in 1913 Atlanta was considerably rougher. Keep in mind what Mann asked us to believe. Once he eluded Conley’s outstretched hand, he was on the sidewalk outside the factory. The streets of Atlanta were teeming with crowds attending the Confederate Memorial Day parade. If he raised his voice to call for help, a crowd would have quickly responded. The life expectancy for Mr. Jim Conley would have been very short if a crowd of 1913 whites found a black man holding the limp (and possibly dead) body of an adolescent white girl in that time and in that place. Yet Mann didn’t know what to do; he didn’t alert any policeman he may have chanced to meet nor the trolley crewmen on his way home. He didn’t speak to anyone till he got home. He raced straight home where his missing mother had already arrived. His parents, certainly not made of stern stuff, advised silence. Even after Frank was arrested the Mann clan remained mum.

The most amazing part of the affidavit is Mann’s statement that his loving parents, worried about the family getting involved in all this, still advised him to return to work where he would be in close proximity to the purported murderer, Jim Conley. Did it never occur to any of them that Conley could just as easily silenced the only witness to see him with the girl’s body? Why advise their beloved son to return to the zone of danger and yet remain silent?

But suppose all of this was true. The Manns thought Conley so dangerous to Alonzo’s safety that they remained silent and let their son go back to work with a homicidal maniac. Once Conley was in police custody that problem was resolved. What was more, a reward was offered for evidence leading to the conviction of the murderer. Did the Manns have no interest in talking about a murderer now in police custody with the additional attraction of a cash reward?

Conley is thought to have died about 1962. Why didn’t Mann come forward then? Surely he didn’t fear the powers of Conley to do him harm extended beyond the grave.

Finally, we come to Conley, “the Prince of Darktown.” To listen to the Frank defenders recite their narrative, Conley was a criminal mastermind who was able to outwit and frame poor Leo Frank and thereafter to withstand the pounding and intense cross-examination of the finest criminal defense attorneys in Georgia of their day. All the time, the criminal mastermind was well-aware that a white boy of fourteen had seen him with the body! Under these circumstances, would Conley have shown up at the National Pencil factory on the Monday after the murder insouciant and confident? Clearly, Conley appeared because he believed he was safe and protected from whatever role he had in this homicide. If Mann saw him on the first floor landing and Conley knew it, why would he loiter at the plant until he was arrested on May 1? Reason and experience with criminal defendants dictates that had the incident occurred as Mann related, Conley would had caught the first freight train headed out of Atlanta and “rode the rods” to any distant geographical point to escape the accusing finger of Mann and the pursuing lynch mob. If Conley did choose to remain in town, wouldn’t he have taken more effective steps to silence a witness than simply warning Mann to shut up?

Furthermore, why would the Moriarty criminal mastermind of Conley not incorporate the Mann incident into his statement and confession to the police? If Conley’s confession was concocted, why would he go to the trouble of inventing the tale of the elevator knowing that Mann stood able to give him the lie? He could have even used Mann to bolster his story by claiming that he carried Mary’s body down the steps at Frank’s direction and dropped it down the trapdoor. Furthermore, Mann could verify that story! “Bring in the office boy and question him!” Conley could have challenged Mann and turned an uncertainty into supporting evidence.

Conley, though, stuck to his version of how the body was transported to the elevator and never volunteered that Mann was a possible witness.

Conley was bringing Mary down the stairs. Where had they been? Why had Frank heard nothing if the assault took place virtually in his office? Additionally, the condition of Mary Phagan’s body when found was quite different than described by Mann. This can only be accurate if Mary was unconscious and then revived when Conley got her to the basement. When Mary’s body was found it was filthy, her dress was torn and she was so blackened by soot and dirt that some of the police could not tell what race she was. (Which could lead to a third explanation for her death. That explanation, unexamined by all the Frank apologists, is that Frank assaulted Mary in the metal room. She was knocked against a machine and fell unconscious. Frank thought her dead and summoned Conley. Conley then finished the job after she came to in the basement. Before dying, Mary apparently put up a real struggle. This explains some of the irregularities in both Frank’s and Conley’s stories. But the preference is to depict Frank as a martyr, a real mensch. This alternative doesn’t please the Frank community. Frank would still be a murderer under the law of almost every state in the union and in 1913 would have gotten the death penalty.)

One member of the Pardons and Parole Board considering Mann’s affidavit pointed out that Mann dropped out of school to work against his parents’ wishes. “Why would a man who wouldn’t obey his parents about school,” [Michael] Wing wondered, “obey them when it came to potentially letting an innocent man hang?”14

Furthermore, Mann showed no concern that day about Leo Frank, a man for whom he expressed respect in later years. Frank, after all, should have still been in the building when Mann returned to find Conley toting a dead girl in his arms. Mann stated he thought he heard movement upstairs. He evidently never considered the fact that Frank — whom he believed to be in his office upstairs — or anyone else still in the factory could have been in peril even decades later when reviewing the case.

And we have the issue of the defense attorneys and police investigators. Evidently, none of them were able to pierce the veil Mann and his family cast about his covert knowledge. This young lad was able to fool even trained investigators who were desperately trying to either free their client or uncover the real story. The defense attorneys interviewed him and decided to use Mann as a witness for Leo Frank. Nevertheless, this naive lad of 14, who had no idea that his information could save an innocent man’s life and who quaked in terror of the now incarcerated Conley, never gave his secret away.

Given the huge problems with the 1982 Mann statement on its face, it is impossible to believe that Mann told the truth in that document. All human experience runs directly contrary to the behavior he attributes to almost every participant in his affidavit.

The Phagan case was cursed from the very beginning with people volunteering “tips” and “clues.” It appears most likely that Alonzo Mann was merely the last of many to offer a fanciful solution to the case.

Since his solution was superficially suited to the Frank defenders’ longstanding press campaign to exonerate Frank, it has received fabulous coverage. Many articles and news statements flatly assert that it closes the case entirely.

As helpful as the Mann statement appeared to be at first blush to the Frank defenders, it does have a major defect; it merely disputes Conley’s testimony about how the body was transported to the place it was found. It does not establish whether Conley or Frank was the murderer.15 After all, Frank was still upstairs when Mann says Conley was carrying the body from that location. What was Frank doing upstairs when Mary Phagan was attacked?

Thus because of these shortcomings and infelicities in Mann’s statement, the document was not of sufficient gravitas or credibility outside of press newsrooms to create the expected popular groundswell which would impel the Georgia Board of Pardons and Paroles to issue a pardon or other exoneration of Frank from culpability in the murder of Mary Phagan.

But the shortcomings outlined above did not give serious pause to the Frank camp.

Because it disputed the Conley testimony, it was immediately ballyhooed, without close consideration, as a complete exoneration of the Leo Frank.

It does no such thing.

1 Busch, Francis X., Notable American Trials: Guilty or Not Guilty (London: Arco Publications, 1957), 74.

2 Phagan (Kean), Mary. The Murder of Little Mary Phagan (Far Hills, NJ: New Horizon Press, 1987), 28.

3 Thompson had worked as an informant infiltrating the Ku Klux Klan for the paper and afterwards became an ardent Frank advocate insofar as Leo Frank’s guilt in the Phagan murder was concerned.

4 State v. Chambers, 240 Ga. 76, 81, 239 S.E. 2d 324 (1977). While written in dissent, this language has been adopted by the Supreme Court in subsequent cases such as Carr v. State, 267 Ga. 701, 482 S.E. 2d 314 (1997). The author has had personal experience with “lie detectors” as well. He was unable to convince an examiner that while he had been a union member, he was not a labor organizer when required to take a test for employment. The job was denied. Georgia will admit lie detector tests if both sides agree, but the reader can envision the value of testimony that both sides see as helpful. Basically, the “lie detector” seeks to “bolster” the credibility of a witness. It is not admissible in most American courts. More recent concern about national security following the terrorist episodes of September 11, 2001 has further eroded the credibility of “lie detectors.” A CBS News, “Not Close Enough for Government Work,” report dated October 8, 2002 reported the National Research Council as stating “National security is too important to be left to such a blunt instrument.”

http://www.cbsnews.com/news/not-close-enough-for-government-work/

5 118 S.Ct. 1261 (1998)

https://www.dauberttracker.com/documents/authorities/Scheffer.pdf

6 Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 246

7 Ibid., 247–261.

8 Ibid., 262.

9 The East Cobb Neighbor of April 6, 1982 as quoted in Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 264–265. Indeed, it did become an issue. Candidate and eventual victor Joe Frank Harris stated he would pardon Frank — even though the governors of Georgia had no legal or constitutional authority to do so.

10 Phagan, The Murder of Little Mary Phagan, 311.

11 Neuroscience is pressing forward on the issue of memory function. Suggestibility in interrogation, memory distortion in the aging process and abuse of substances (such as alcohol) are all at issue in Mann’s recollections. Memories of traumatic events have been shown to change with time and it has been convincingly demonstrated that in some cases that physic phenomena in the nature of memories are often created for traumatic events that did not actually happen. These are all problems with honest witnesses, let alone witnesses that may have been influenced by a desire for fame, notoriety or mere lucre.

12 See Steve Oney, And the Dead Shall Rise (New York: Pantheon, 2003). An example would be at page 343. There were times when the audience would laugh or applaud, but the jury, when out of the courtroom, were not sure for whom the demonstrations were intended. In newspaper interviews and public appearances Oney flatly states there were no “Kill the Jew” chants.

13 Brief of Evidence contains the entire direct testimony of Alonzo Mann in 16 sentences, most of which deal with who was in the factory. The cross-examination was but three sentences dealing with the time Mr. Frank was out of the office.

Brief of the Evidence. In the Supreme Court of Georgia, Fall Term, 1913, Leo M. Frank, Plaintiff in Error vs. State of Georgia, Defendant in Error, 123.

14 Clark J. Freshman, “By the Neck Until Dead: A Look Back At a 70 Year Search for Justice,” American Politics, January, 1988, 31.

15 Logic would follow that disproving a critical part of Conley’s testimony does and should create doubt about other parts of his testimony: Falsum in unum, falsum in omnibus. But the same maxim applies to Mann’s statement — which was not exposed to days of grueling cross-examination by skilled attorneys.