Oh, would some Power give us the gift

To see ourselves as others see us!

-Robert Burns

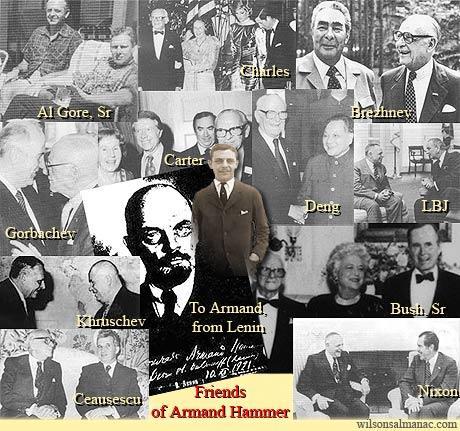

There are few things that provide quite as illuminating a contrast as comparing a man’s testament of his own life against those accounts given by others (friend and foe, alike). In that spirit, then, here is an account of the life of Armand Hammer, the Jewish businessman, oil magnate, concessionaire and art collector, who in his telling was a crusader for human rights and the scourge of cancer. The picture that emerges of Dr. Hammer in the eyes of others (and sometimes in declassified documents and secret recordings) is a quite different face than the one Hammer presented to the world. Here is Part One of a five-part series.

Lenin’s Willing Industrialist: The Saga of Armand Hammer, Part I: Roots and Russia

In public relations agent Carl Blumay’s account of his more than twenty years in service to Armand Hammer, The Dark Side of Power: The Real Armand Hammer, he relates how carefully Hammer crafted his “disarming, grandfatherly public persona” (Blumay 363) and how the man behind the meteoric rise of Occidental Petroleum never missed an opportunity to disprove the darker rumors surrounding his empire. During his career at Occidental, Blumay himself had become a prop in this campaign, conscripted against his will at times. When, for instance, word of “Occidental’s revolving door” (363) hire-and-fire policy was making the rounds, Dr. Hammer made a constant routine of asking the PR man in public how long he had been working with Hammer. He did this to present an image to the world of “the eighty-one-year-old paterfamilias of one of the world’s great multinational corporations standing side-by-side with his devoted sixty-eight-year-old retainer of a quarter century” (Ibid.). Hammer performed this routine using Blumay so frequently that it eventually approached the level of vaudeville with Blumay gritting his teeth in a forced smile while replying with the requisite “twenty-five years” to the day’s audience, whether it was at a board meeting, fundraiser, or an art gallery.

One would be hard-pressed to find a more auto-hagiographic tale than the one related in Steve Weinberg’s Hammer: The Armand Hammer Story, which “told the entertaining story of a saintly but shrewd man whose life consisted of one triumph after another” (Blumay 437). The book’s coauthor put it mildly when he said that “a lot of sanitizing went on” (Ibid.) in the writing. He was being a bit more candid when he related that “[Hammer’s] character was my creation in a fictional enterprise.” Although the author was compensated to the tune of $500,000 plus another roughly $72,000 in expenses for casting his quarry in a nigh-on saintly light, he still walked away from the project feeling as if he had “flogged every atom of my soul.”

The steps that Armand Hammer took to exaggerate (or even invent) certain aspects of his business abroad (especially in Russia) while downplaying others, were sometimes undercut by his vanity and paranoia.

Hammer’s Nixonian obsession with recording and espionage, “what he called James Bond stuff” (Edward J. Epstein, Dossier: The Secret History of Armand Hammer, 18), involved using moles, spies, and hidden surveillance techniques he’d picked up during his extensive stays in the Soviet Union to gain intelligence and leverage on others. “Hammer found this secret taping system especially useful for recording sensitive events, such as the disbursement of bribes to which he did not want even his confidential secretaries to be privy” (Ibid.). One of Hammer’s mistakes in this enterprise was to enlist his son Julian in the cloak-and-dagger. Julian Hammer was a quintessential case of affluenza, a princeling who seemed to be above the law. Armand Hammer’s son had been arrested for shooting and killing his friend at the age of 24. Numerous other violent and very public outbursts involving guns and drugs followed, but his police record eventually disappeared from the county files. (According to Armand Hammer, this was none of his doing and was probably attributable to poor clerical competency among California public sector employees.)

The main problem with Hammer’s bugging and surveillance operation, though, was not familial nepotism, but that he was unknowingly collecting a trove of evidence against himself that could be potentially damning one day, assuming it fell into the hands of a journalist who wasn’t a friend or on his payroll. Hammer counted the Sulzberger’s New York Times among his allies going back at least as far as when The Times’ notorious Walter Duranty (who won a Pulitzer for his work in covering up the Holodomor) helped him craft his first autobiography, The Quest of the Romanoff Treasure. This tight relationship with the Times might help explain why he initially let the Gray Lady’s own Edward J. Epstein into his orbit. The journalist who eventually defected from the standard effusive and glowing picture of Dr. Armand Hammer was able to gather enough information to write The Secret History of Armand Hammer, which forms a perfect tonic to the poisonous myths surrounding one of the most consummate sociopaths of the modern era. Carl Blumay claims that Epstein would have never gotten close to Armand Hammer during his tenure working PR for him. But Armand’s obsession with “the notion of using his friendship with Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger” (Blumay 392), along with an over-weaning desire for fame and attention, caused him to lower his guard. It also led to the first public revelations regarding just what Armand Hammer had been up to in Russia, and on behalf of the Communists in America.

***

To understand Armand Hammer, it is necessary to first know something about his father, Julius Hammer. Julius Hammer was a Jewish immigrant from Russia who came to New York ostensibly to practice medicine and thrive as a small businessman. He founded a pharmaceutical supplies concern called Allied Drug and Chemical Corporation. This company was created in “a secret partnership with the Bolshevik government” (Blumay 40). State Department files claim Armand’s father was “one of the first to establish one of the ‘front’ corporations and purchasing agencies” that were controlled by “Soviet-Jewish elements under the direction of the Soviet Government of Russia” (41).

The depth of Julius Hammer’s ideological zealotry is hardly disputed, even by Armand Hammer’s own account (though he soft-pedaled his father’s fanaticism as misguided, starry-eyed idealism – a standard (and largely false) account of Jewish involvement in Communism). Victor Hammer, Armand’s brother, said he got his name because it meant “victory over capitalism” (Blumay 38). Armand Hammer would sometimes claim his father named him after Armand Duval, a character in La Dame aux Camélias by Alexandre Dumas, fils, but later in life Hammer would admit that he was named in honor of the arm-and-hammer symbol of the Socialist Labor Party. “Decades later, Armand would use the arm-and-hammer-insignia as the flag on his yacht” (Epstein 35).

A Scotland Yard report confirmed the elder Hammer’s unalloyed ardor for Communism, and also that he worked in tandem with Ludwig Martens (a Russian-born communist appointed ambassador to the United States by Vladimir Lenin) to help grow the “Communist Party of the United States in America” (Blumay 36), especially in New York, alongside Jewish-American economist Isaac Hourwich.

Edward Epstein corroborates this report from across the pond, and also shows that Julius Hammer’s circle of fellow-travelers included not only intellectuals, but men of action, revolutionaries such as Boris Reinstein “who had been expelled first from Russia and then Germany, Switzerland, and France for his radical activities” (Epstein 34). Reinstein had done two years in prison for his involvement in a terrorist bombing, as well. He and Julius Hammer had both come “from Jewish ghettos in the same area of southern Russia” (34).

In later life Armand Hammer would try to downplay his father’s Jewish identity (and his own) to grease the wheels of his oil concessions in the Middle East, since Israel was not exactly enjoying popularity among the various pan-Arab revolutionaries when he made his successful wildcat play for Libya. Armand would even ridiculously claim that he and his family were Unitarians, but the record shows that Julius Hammer was a strongly-identified Jew. Like many Jews though, he yearned to have it both ways, to reap the benefits of assimilation while gaming the nepotistic perks that come with what John Derbyshire calls “absimilation” (sic). Although this attitude displayed by Julius Hammer (and inherited by his sons) may seem schizophrenic on the surface, it reveals itself as simply expedient when studied closer: When being Jewish proved an impediment to making money, the Hammers downplayed being Jewish. In those circumstances when it was advantageous to be Jewish, no such pains were taken.

Armand Hammer’s brother Victor claimed in his talks with Carl Blumay that his father was “violently anti-Semitic” (38), but to say that he was extremely cautious would be more accurate. Armand Hammer was given toward a tendency to invoke the specter of pogroms at a moment’s notice in his memoirs, but according to Victor Hammer “Pop’s parents were merchants who prospered under the Czar and denied being Jewish” (Ibid.). Dr. Julius Hammer’s obscurantism extended to his medical practice (more on that later), with Victor claiming that “every time he delivered a baby, if Jewish parents gave their children what he considered a Jewish-sounding first name, he changed the name on the birth certificate.”

Screenwriter Michael Herr (whose credits include Full Metal Jacket and Apocalypse Now) mentions in his book on Stanley Kubrick that Jews can comfortably be themselves (that is Jewish) only in the presence of other Jews. The phenomenon is repeatedly apparent in the lives of both Armand Hammer and his supposedly “violently anti-Semitic” father. Epstein describes this cultural milieu in which the younger Hammers came of age, in New York neighborhoods “strictly divided between Jewish and Irish immigrants” (34):

The burning issue was assimilation: should Jews remain within their own culture and seek a Judaic form of socialism, or should they seek a nonsectarian form? The Jewish radicals subscribed to the latter position. They passionately rejected ghettoization. In doing so, as social critic Irving Howe points out, “the Jewish radicals … hoped to move from the yeshiva to modern culture, from shtetl to urban sophistication, from blessing the Sabbath wine to declaring the strategy of international revolution. They yearned to bleach away their past and become men without, or above, a country” (34–35)

Despite such pronouncements, it was very typical for Jewish radicals to retain a strong Jewish identity, quite often implicitly and involving a great deal of self-deception.

That his father subscribed to radical, violent political revolution does not necessarily imply that Armand Hammer was foreordained to become a Communist, a Communist sympathizer, or a subversive agent of some kind. But it seems that the apple did not fall far from the tree. Despite enjoying all the advantages of American capitalism while incurring none of the costs of Communist revolution, Armand remained Red at heart. These paradoxes made life quite hard for PR man Carl Blumay since he was charged with making sure that allegations against Armand Hammer rarely made it to intelligence agency archives, that nothing unsavory would hinder Hammer’s position in politics or business, or be leaked to the press where the charges could hurt Hammer’s reputation with the public. When Carl Blumay was acting as aide-de-camp to Armand Hammer against one such round of allegations (this time from a member of the Catholic War Veterans), he took the complaint to Armand’s brother Victor and asked him “how to temper his brother’s Soviet ardor” (Blumay 36). Victor’s response was to laugh and to say, “Armand has always looked to the Kremlin with the same kind of reverential regard a deeply devoted Moslem pays to Mecca” (Ibid.).

Revolution (first in Russia and then in Libya) was good to Armand Hammer. Revolution was a kind of religion for him. And even better, revolution made him rich.

When Armand Hammer was pressed regarding his loyalties or his ideology, his answer rarely wavered. In Hammer, he says “I always … tell the Russians that I am a capitalist, that I believe our system is better than theirs and that I want us to coexist peacefully” (159). The pretext of peace glosses much of Armand Hammer’s description of his own philosophy. A claim to be helping the effort toward détente, a thawing of relations between East and West during the Cold War, and a desire to avert nuclear war (for the sake of future generations, of course) allowed him to increase his fortune as well as the influence of Communism, all while shifting attention away from his activities or hiding his true intent behind a veil of philanthropy.

As a result, his jaunts in his Gulfstream jet, OXY 1, to visit characters like genocidal dictator Nicolae Ceaușescu were written off as attempts to find some common ground between two opposing political systems. Incidentally, before Ceausescu was found guilty of genocide and executed, Hammer related to Carl Blumay that the General Secretary of the Romanian Communist Party was his “best friend” (251), not to mention “a great leader, a fine, warmhearted man, and a humanitarian who loves his people and has compassion for them” (Ibid.). The throwaway addendum that “he’s so easy to do business with” gets a little closer to the truth of why Hammer (as usual) was willing to look the other way to enrich himself while people were dying.

A memorandum from assistant director of domestic intelligence, William Sullivan, to J. Edgar Hoover classified “Hammer [as] a type who would do business with the devil if there was a profit in it” (Epstein 211). This was only slight hyperbole.

***

Although intelligence gathering had begun on the Communist activities of the Hammers since at least as early as 1921 (under the aegis of a young Justice Department assistant named J. Edgar Hoover), including “a tip from an informant alleging that Hammer was a courier for the newly-organized Communist International” (Epstein 22), it wouldn’t be the political activities of the Russian-Jewish émigré and his son that first exposed them to the light of the law. Rather it was the gross medical malfeasance of Dr. Julius Hammer and his son Armand, then still in medical school:

A woman had died after undergoing an abortion at the clinic at Hammer’s house. The dead woman was Marie Oganesoff, the 33-year-old wife of a Russian diplomat who had come to America from the Czarist regime. According to the testimony of her chauffeur, she had gone to the Hammer house for the abortion on July 5 and collapsed when she returned home later that day. … When questioned by prosecutors, Julius Hammer did not deny that an abortion had been performed, but he claimed that it was medically justified, and that he, as her doctor, had the right to make such a decision. Nevertheless, he was indicted (Epstein 42).

Julius Hammer had had earlier close calls with the law, having been surveilled in the belief that he may have been the one supplying material for bombs given to subversives and of furnishing dynamite to the radical Boris Reinstein. This suspicion was especially harbored by the NYC Red Squad formed initially “to counter a spate of anarchist bombings in Manhattan” (Epstein 36) and alluded to in an interview Victor Hammer gave to Carl Blumay, in which he admitted “Pop even gave dynamite to a young radical” (Blumay 39). Considering that Julius Hammer was a doctor involved in the pharmaceutical supply business, it would have been easy for him to amass precursors required to make explosives without arousing suspicion, although at this remove it is hard to say which violent crimes he either did or did not help facilitate.

But the law eventually caught up with him anyway.

On June 26, 1920, “the jury found Julius Hammer guilty of first-degree manslaughter. The judge then pronounced his sentence: three and one half to twelve years of hard labor at Sing-Sing” (Epstein 42).

The most provocative aspect of this whole morbid affair was that journalist Edward J. Epstein claims Armand Hammer knew that he had let his father go to prison as an innocent man (or at least one who wasn’t guilty of this specific crime in question):

He would keep his knowledge a secret for three decades. Then, afraid that he was dying, he explained to his longtime mistress that it was he, not his father, who had performed the illegal abortion in 1919. He was then only a first-year medical student, unlicensed to practice medicine, and would certainly have gone to prison if his father had not stepped in to take the blame. Ordinarily, doctors in New York State were permitted leeway in performing such abortions and were rarely prosecuted (46).

As with so many other aspects of Armand Hammer’s life (especially suspected crimes) there is an aura of mystery that remains, even after the files from the collapsed Soviet Union have been disgorged to prove Hammer’s guilt in other realms. Adding ‘back-alley abortionist’ and ‘manslaughter’ to his curriculum vitae would certainly run counter to the image Hammer yearned to project of himself, but it certainly rings truer than the implausible obstetrical escapades he describes in his autobiography. If Armand Hammer would have the reader believe that he “missed the lecture on breech deliveries” (Hammer 83) at Columbia College but was somehow able to skim through Cragin’s Obstetrics in the bathroom of an apartment, “memorize the illustrations on technique” (84) and then perform an emergency cesarean section on an imperiled woman giving birth, then one could be forgiven for thinking he was capable of killing a woman in a botched curetting, letting his father take the blame, and continuing on undeterred in his quest for money and power.

With the old radical warhorse Julius Hammer temporarily sidelined by his prison stint, his sons were ready to take up the mantle of world revolution. Armand was the older, more calculating, and ambitious of the two brothers, and it was while acting in his capacity as go-between for his father in prison and the Comintern on the outside that Armand Hammer would first execute his father’s wishes and then start to fulfill his own much grander schemes for power at any cost. Armand Hammer was about to become one of the most influential players on the global scene and would play no small part in shaping the twentieth century, mostly for the worse.

Go to Part 2.

Works Cited

Blumay, Carl. The Dark Side of Power: The Real Armand Hammer. Simon & Schuster, 1992

Epstein, Edward J. Dossier: The Secret History of Armand Hammer. Random House, 1996.

Hammer, Armand and Neil Lydon. Hammer: The Armand Hammer Story. Perigee Trade, 1988.

One such was revealed by Christopher Andrew, the official historian of Britain’s security service MI5, in 2009, when he said in his magisterial history, that at the end of the war there was a ban on the service recruiting any more Jews to its ranks because of fears they would be disloyal. This informal ban stood for thirty years. It was a startling revelation, but produced little further comment.

One such was revealed by Christopher Andrew, the official historian of Britain’s security service MI5, in 2009, when he said in his magisterial history, that at the end of the war there was a ban on the service recruiting any more Jews to its ranks because of fears they would be disloyal. This informal ban stood for thirty years. It was a startling revelation, but produced little further comment.