Review of Thomas Martin’s “The Victory of Humanism”

The Victory of Humanism: The Psychology of Humanist Art, Modernism, and “Race”

Thomas Martin

Palm Coast, FL: Backintyme, 2011; 177 pages

There can be little doubt that in historical perspective, perhaps the most important upheaval in Western culture has been the decline of aristocratic culture. This is apparent, for example, in two recent books that have influenced my thinking, Ricardo Duchesne’s The Uniqueness of Western Civilization and Andrew Fraser’s The WASP Question (my review will appear in the first issue (June) of Radix, a new magazine edited by Alex Kurtagic and Richard Spencer). For Duchesne, aristocratic individualism is the key to understanding the uniqueness and creativity of the West. Fraser laments the decline of Indo-European aristocratic culture, beginning with the Puritan revolution of the 17th century and carried to its logical conclusion in America with the defeat of the South in the Civil War.

Thomas Martin’s The Victory of Humanism focuses on the decline of aristocratic culture in Western art. Following the “perfection of antiquity,” the breakthrough occurred in the Renaissance with the work of Leonardo Da Vinci, Raphael, and Michalangelo.

A critical observation by Vasari is that those artists achieved perfection by only portraying the beautiful. They did this by using the most beautiful examples of the human body or nature. In this way, they achieved the idealization or perfection of both body and nature. In fact, Vasari goes so far as to say that Michelangelo was so wedded to the idea of perfection that he had a policy of never doing a portrait of a living person.This would have been descending away form the ideal in the “mind of God” or the human mind, and losing himself in the particular of the empirical.

Martin correctly points out that this sense of ideal human form is an innate part of human psychology. Evolutionary psychologists have shown that the faces that humans find attractive are generalized. That is, faces that are produced by averaging dozens of real photos are judged attractive. Martin expands on this by suggesting that “there is a certain nobility in the generalized face, which helps create the sense that it is ideal. Seeing the face that is in the mind takes the viewer above or out of this world and into the mind, the most powerful and noble part of our bodies.”

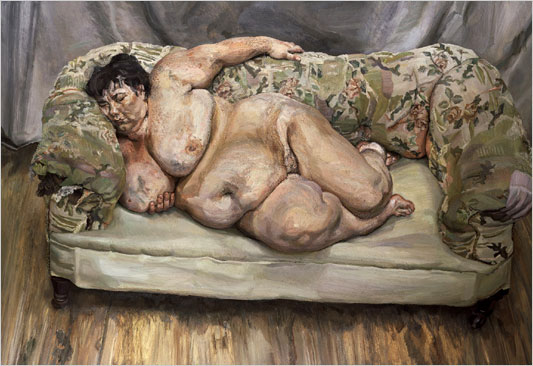

Martin then describes the decline of the ideal and the rise of egalitarianism, particularlity, and vulgarity in art. This did not happen all at once. In the 17th and 18th centuries, artists “took a dim view of raw nature”; Frederick Art, a historian, notes that “in the age of the Baroque, they evidently wanted to smooth and regulate all nature and make, as it were, domestic pets of the rivers and mountains.” Not until the end of the 19th century did the crudeness of nature become an artistic ideal. Martin notes that “Nature per se was viewed as vulgar and disgusting, while refined culture was viewed as beautiful and a relief from vulgar, oppressive and confining nature.”

Whereas nature was seen as confining and oppressive, in the long run “high art formalism” came to be seen as oppressive. Aesthetics was “displaced to oppose the confining upper class during the French Revolution”; already in the 19th century, “artists were beginning to find beauty and greatness themselves to be confining, and sought escape into the chaos and irregularities of nature and personal experience. This defines relativism, particularism and the decline of standards.”

Ultimately, this trend derives from egalitarian political philosophies emphasizing the natural rights of the individual and hostile to traditional social hierarchies that, as both Duchesne and Fraser note, are Indo-European in origin. Classical Western culture emphasized reason controlling emotion and political dominance by a natural aristocracy. “The ideal of modernism was that instead of reason and the upper class controlling the appetites and the lower class, respectively, the reverse should be the case.” As exemplifying this trend toward egalitarianism, Martin quotes an article by eugenicist John Glad who found that most people disagreed the idea that people with high intelligence should have more children.

These trends might be termed “egalitarian individualism,” as opposed to the aristocratic individualism described by Duchesne (see above) that has been so central to classical Western art. For Martin, modernism fundamentally reflects aspirations for “a deified and unlimited individualism.” This can be seen in everything from political thinking to advertising campaigns that appeal to people’s uniqueness and individuality—the “culture of narcissism” and the glorification of individual suffering at the hand of an oppressive social order. More and more art was designed to appeal to low and vulgar tastes, the aristocracy seen as corrupt and morally debased. “Over the last two centuries, evil was displaced from the body, from sexuality, and from the lower class, to the upper class, their art and proper morals or etiquette.” This was then extended to the bourgeois upper classes, as in the film Titanic. Whereas “classicists emphasize limits on behavior and intelligence, and the need for social control on native inclinations to evil, hostility or crime,” modernists “experience limits as claustrophobic imposition from the group. So they rebel against anything limiting, such as conceptions of class, sex, ‘race’, and native intelligence.” [Note that the word ‘race’ is in quotation marks, as it is in the subtitle. This suggests that Martin does not believe in the reality of race, but Martin informs me that it was because of the publisher’s insistence.]

Although ‘race’ appears in quotation marks, Martin notes at African-Americans and the non-West have benefited greatly from the general trends of modernism. Blacks now sit in judgment of White culture and are routinely deified in the media—literally, as with all those films where Morgan Freeman is portrayed as America’s “spiritual presence-in-chief) “Modernists today become worthy when they hate their own civilization, or feel unworthy in the face of non-Westerners. To consider oneself unworthy is a sure sign of social virtue today.”

As with Andrew Fraser in The WASP Question, Martin yearns for the classical world of hierarchy and the primacy of reason “able to suppress the worst of human nature.” He realizes that this world cannot be revived, but nevertheless hopes that we could “somehow return to rejecting our animal aspect.”

There is a lot to like about this book. Martin moves adeptly (but at times incongruously) between a wide range of genres, from high art and opera plots, to Hollywood films and television. The general thrust of the book certainly fits with the decline of aristocratic culture that is so central to the modern age. On the negative side, there is no mention of ethnic competition over the construction of culture, as emphasized in discussions of Jewish influence on this site (e.g., Edmund Connelly, Lasha Darkmoon and Michael Colhaze). My view is that we must understand both the ethnic roots of the egalitarian trends of Western culture stemming ultimately from evolution as northern hunter-gatherers, but also realize that the the rise of Jews as a hostile elite has been an important aspect of the debasement of Western culture in the direction of vulgarity and hedonic individualism since at least the beginning of the 20th century. Certainly, several of the movements discussed by Martin (the 1960s counter-cultural revolution, the rise of Blacks to the status of moral paragons, and the ideology of multiculturalism and hostility toward the people and culture of the West) cannot be understood without a consideration of Jewish influence.

Martin is correct that we can’t go back to earlier Western social forms which were based on a hereditary aristocracy that achieved their position as a result of the military accomplishments of ancestors. I do think, however, that in the early 20th century the West was headed in the direction of developing a natural aristocracy based on intelligence, moral probity, and the possibility of upward and downward social mobility. This was the heyday of eugenics as a belief system common among Western elites, both liberals and conservatives. An important component of this worldview included an understanding of the genetic basis of intelligence and behavior (see, e.g., Lothrop Stoddard’s Revolt of the Underman, republished by Alex Kurtagic’s Wermod & Wermod).

This world was shattered; ultimately it was a victim of the outcome of World War II, even though eugenics was not expunged from polite society until the 1960s as a result of an energetic campaign by Holocaust-haunted intellectuals bent on striking a blow against their ethnic competitors. If that vision of society had prevailed, and, correlatively, if the West had rejected the model of multiculturalism fueled by massive non-White immigration promoted by Jewish intellectual and political activism, it is quite reasonable to suppose that it would have had a very large and positive influence on the world of art.

Comments are closed.