Differences between the Eastern European immigrant community in the US and the older German-Jewish establishment — and their commonalities

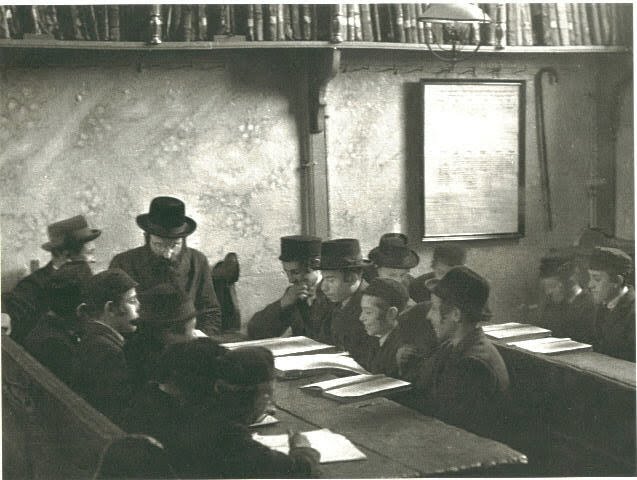

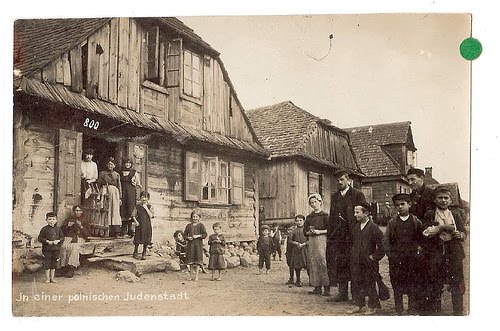

Eastern European Shtetl Jews; photos from “Rare Photographs and Images of Shtetl Life“

In his VDARE article of April 22, “Eastern European Jews And The Case Of the Marginalized Elite,” Paul Gottfried claims that I fail to make important distinctions among Jewish groups:

Though Kevin MacDonald argues his theory about Jewish group behavior ably, I believe it is unwarranted to generalize about the social behavior of all Jews simply because of the behavior of Eastern European Jews. …We are clearly dealing with a group that embraces all kinds of Leftist causes, most of which have a destabilizing effect on what remains of a traditional Christian society. Let me repeat: I don’t find anything about this behavior that has characterized all Jews at all times (unlike MacDonald).

This article summarizes some of my comments on different groups of Jews, some of which may have gotten a bit lost in the shuffle. In fact, beginning with my first two books on Judaism, I have repeatedly discussed differences among Jewish groups (e.g., IQ differences between Ashkenazi and Sephardic groups in chapter 7 of A People That Shall Dwell Alone). This includes the important distinction between Eastern European Jews and Western European Jews, beginning with Chapter 6 of Separation and Its Discontents (1994) on Jewish strategies to minimize anti-Semitism.

It has often been critically important for Jews to be able to present a divided front to the gentile society, especially in situations where one segment of the Jewish community has adopted policies or attitudes that provoke anti-Semitism. This has happened repeatedly in the modern world. A particularly common pattern during the period from 1880 to 1940 was for Jewish organizations representing older, more established communities in Western Europe and the United States to oppose the activities and attitudes of more recent immigrants from Eastern Europe (see note 20). The Eastern European immigrants tended to be religiously orthodox, politically radical, and sympathetic to Zionism, and they tended to conceptualize themselves in racial and national terms—all qualities that provoked anti-Semitism. In the United States and England, Jewish organizations (such as the American Jewish Committee [AJCommittee]) attempted to minimize Jewish radicalism and gentile perceptions of the radicalism and Zionism of these immigrants (e.g., Cohen 1972; Alderman 1992, 237ff). Highly publicized opposition to these activities dilutes gentile perceptions of Jewish behavior, even in situations where, as occurred in both England and America, the recent immigrants far outnumbered the established Jewish community.

This difference between the Eastern European immigrant community and the German-Jewish establishment in the US is a central theme of “Jews, Blacks, and Race” (in Samuel Francis (Ed.), Race and the American Prospect: Essays on the Racial Realities of Our Nation and Our Time [The Occidental Press, 2006]):

Anti-Jewish attitudes that had been common before [World War II) declined precipitously, and Jewish organizations assumed a much higher profile in influencing ethnic relations in the U.S., not only in the area of civil rights but also in immigration policy. Significantly this high Jewish profile was spearheaded by the American Jewish Congress and the ADL, both dominated by Jews who had immigrated from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1920 and their descendants. As indicated below, an understanding of the special character of this Jewish population is critical to understanding Jewish influence in the United States from 1945 to the present. The German-Jewish elite that had dominated Jewish community affairs via the American Jewish Committee earlier in the century, gave way to a new leadership made up of Eastern European immigrants and their descendants. Even the AJCommittee, the bastion of the German-Jewish elite, came to be headed by John Slawson [in 1943], who had immigrated at the age of 7 from the Ukraine.

The AJCongress, a creation of the Jewish immigrant community, was headed by Will Maslow, a socialist and a Zionist. Zionism and political radicalism typified the Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe. As an indication of the radicalism of the immigrant Jewish community, the 50,000- member Jewish Peoples Fraternal Order was an affiliate of the AJCongress and was listed as a subversive organization by the U.S. Attorney General. The JPFO was the financial and organizational “bulwark” of the Communist Party USA after World War II and also funded the Daily Worker, an organ of the [Communist Party USA], and the Morning Freiheit, a Yiddish communist newspaper. Although the AJCongress severed its ties with the JPFO and stated that communism was a threat, it was “at best a reluctant and unenthusiastic participant” in the Jewish effort to develop a public image of anti-communism—a position reflecting the sympathies of many among its predominantly second- and third-generation Eastern European immigrant membership. Concern that Jewish communists were involved in the civil rights movement centered around the activities of Stanley Levison, a key advisor to Martin Luther King, who had very close ties to the Communist Party (as well as the AJCongress) and may have been acting under communist discipline in his activities with King.

On the other hand:

The Southern Jewish community was relatively small compared to the much larger Jewish population that immigrated from Eastern Europe between 1880 and 1924, and had relatively little national influence. Southern Jews immigrated in the 19th century mainly from Germany, and they tended toward political conservatism, at least compared to their Eastern European brethren. The general perception of northern Jews and southern blacks and whites was that southern Jews had adopted white attitudes on racial issues.

Moreover, southern Jews adopted a low profile because southern whites often (correctly) blamed northern Jews as major instigators of the civil rights movement and because of the linkages among Jews, communism, and civil rights agitation during a period when both the NAACP and mainstream Jewish organizations were doing their best to minimize associations with communism. (Jews were the backbone of the Communist Party USA, and the CPUSA agitated on behalf of black causes.) It was common for southerners to rail against Jews while exempting southern Jews from their accusations: “We have only the high-type Jew here, not like the kikes in New York.”

And in conclusion:

Throughout this essay I have noted the contrast between the German-Jewish immigrants who came to the U.S. in the mid- to late-19th century and the massive Eastern European Jewish immigration that completely altered the profile of U.S. Jewry in the direction of political radicalism and Zionism. The former group of [German-Jewish] immigrants rather quickly became an elite group, and their attitudes, as in Germany, were undoubtedly more liberal than similarly situated non-Jews of the time [see Chapter 5 of Separation and Its Discontents). Nevertheless, they tended to political conservatism and, whether living in the North or the South, they did not attempt to radically alter the folkways of the white majority, nor did they engage in radical criticism of non-Jewish society. I rather doubt that in the absence of the massive immigration of Eastern European Jews between 1880 and 1920 that the U.S. would have undergone the radical transformations of the last 50 years.

The Eastern European immigrants and their descendants were and are a quite different group. These immigrants originated in the intensely ethnocentric, religiously fundamentalist shtetl communities of Eastern Europe. These groups had achieved a dominant position economically throughout the area, but they were under intense pressure as a result of anti-Jewish attitudes and laws. And because of their high fertility, the great majority of Eastern European Jews were poor. Around 1880 these groups shifted their focus from religious fanaticism to complex mixtures of political radicalism, Zionism, and religious fanaticism, although religious fanaticism was in decline relative to the other ideologies. Their political radicalism often coexisted with messianic forms of Zionism as well as intense commitment to Jewish nationalism and religious and cultural separatism, and many individuals held various and often rapidly changing combinations of these ideas.

The two streams of political radicalism and Zionism, each stemming from the teeming fanaticism and passionate ethnocentrism of threatened Jewish populations in 19th-century Eastern Europe, continue to reverberate in the modern world. In both England and America the immigration of Eastern European Jews after 1880 had a transforming effect on the political attitudes of the Jewish community in the direction of radical politics and Zionism, often combined with religious orthodoxy. The immigrant Eastern European Jews demographically swamped the previously existing Jewish communities in both countries, and the older communities were deeply concerned because of the possibility of increased anti-Semitism. Attempts were made by the established Jewish communities to misrepresent the prevalence of radical political ideas among the immigrants. However, there is no doubt that immigrant Jews formed the core of the American left at least through the 1960s; as indicated above, Jews continue to be an important force on the left into the present. One expression of the passionate ethnocentrism the immigrant Jews and their descendants is hatred directed at the non-Jewish world. In other words, at the conscious level, the Jewish activists who had such a large effect on the history of racial relations in the U.S. were motivated to a considerable extent by their hatred for the white power structure of the U.S. because the white power structure represented the culture of an outgroup….

Indeed, my curiosity about Eastern European Jews led to my essay “Zionism and the Internal Dynamics of Judaism,” which delves into the details about the demographic profile of Eastern European Jews, the extreme economic and political pressures they lived under, and the radical attitudes that resulted (religious fanaticism with roots in Hasidism, leftist political radicalism, and intense commitment to Zionism). (Indeed, the psychological intensity and the aggressiveness of these immigrants impressed me so much that I included them as traits that facilitate Jewish activism [“Background Traits for Jewish Activism,” p. 24ff].) The interesting thing about this phenomenon is that this Eastern European population had overshot its ecological niche, so that poverty was widespread. But despite this, they continued to have very high fertility, which I theorize was due to their intense collectivism and ethnocentrism rooted in the religious fundamentalism that typified this population prior to their attraction to political radicalism and Zionism). (On the other hand, individualists typical of Western societies tend to delay marriage and have fewer children during times of economic hardship [e.g., the depression of the 1930s].)

The result was a “feed forward” process in which Jewish economic desperation and anti-Jewish attitudes and restrictions on Jews increased over time, as Jews, never abandoning but rather expanding their economic niche of middleman minority, became increasingly ruthless and aggressive in their business practices. (For example, Albert Lindemann notes the effects of the influx of a number of Russian Jews to Atlanta in the early twentieth century — often described as “barbaric and ignorant” by the established German Jewish community. These Jews often owned saloons and were accused of selling liquor to Blacks, thus contributing to public disorder. After the race riot of 1906, the liquor licenses of several Jewish-owned saloons were revoked” [from my review). And finally, commenting on Jews in Czarist Russia, Lindemann noted that Jews were often in the position of managing peasants for Russian aristocrats and in lending money and providing alcohol to them as innkeepers. Stereotypes of Jews as prominent in the liquor trade, usury, prostitution, and criminal activity were hardly figments of anti-Semitic imaginations (from my review).

This thesis was previewed in Chapter 3 of The Culture of Critique (1998) and contrasts with the views of David R. Verbeeten who, as summarized by Gottfried, attempts to find the roots of Eastern European Jewish radicalism as deriving from their experience in America:

Ultimately this population explosion in the context of poverty and politically imposed restrictions on Jews was responsible for the generally destabilizing effects of Jewish radicalism on Russia up to the revolution. These conditions also had spill-over effects in Germany, where the negative attitudes toward the immigrant Ostjuden contributed to the anti-Semitism of the period (Aschheim 1982). In the United States, the point of this chapter is that a high level of inertia characterized the radical political beliefs held by a great many Jewish immigrants and their descendants in the sense that radical political beliefs persisted even in the absence of oppressive economic and political conditions. In Sorin’s (1985, 46) study of immigrant Jewish radical activists in America, over half had been involved in radical politics in Europe before emigrating, and for those immigrating after 1900, the percentage rose to 69 percent. Glazer (1961, 21) notes that the biographies of almost all radical leaders show that they first came in contact with radical political ideas in Europe. The persistence of these beliefs influenced the general political sensibility of the Jewish community and had a destabilizing effect on American society, ranging from the paranoia of the McCarthy era to the triumph of the 1960s countercultural revolution.

The immigration of Eastern European Jews into England after 1880 had a similarly transformative effect on the political attitudes of British Jewry in the direction of socialism, trade-unionism, and Zionism, often combined with religious orthodoxy and devotion to a highly separatist traditional lifestyle (Alderman 1983, 47ff). “Far more significant than the handful of publicity seeking Jewish socialists, both in Russia and England, who organized ham sandwich picnics on the fast of Yom Kippur … were the mass of working-class Jews who experienced no inner conflict when they repaired to the synagogue for religious services three times each day, and then used the same premises to discuss socialist principles and organize industrial stoppages” (Alderman 1983, 54). As in the United States, the immigrant Eastern European Jews demographically swamped the previously existing Jewish community, and the older community reacted to this influx with considerable trepidation because of the possibility of increased anti-Semitism. And as in the United States, attempts were made by the established Jewish community to misrepresent the prevalence of radical political ideas among the immigrants (Alderman 1983, 60; SAID, Ch. 8).

Understanding this group is indeed critical for understanding Jewish influence in the West as well as the political dynamics of Israel. It is also critical to understanding the role of Jews in Bolshevism. In my review of Yuri Slezkine’s The Jewish Century, I noted:

Slezkine devotes one line to the fact that Jewish populations in Eastern Europe had the highest rate of natural increase of any European population in the nineteenth century (p. 115), but this was an extremely important part of Eastern Europe’s “Jewish problem.” Anti-Semitism and the exploding Jewish population, combined with economic adversity, were of critical importance for producing the great numbers of disaffected Jews who dreamed of deliverance in various messianic movements—the ethnocentric mysticism of the Kabbala and Hasidism, Zionism, or the dream of a Marxist political revolution. Jews emigrated in droves from Eastern Europe but the problems remained. And in the case of the Marxists, the main deliverance was to be achieved not by killing Judaism, as Slezkine suggests, but by the destruction of the traditional societies of Eastern Europe as a panacea for Jewish poverty and for anti-Semitism. In fact, the vast majority of Jews in Eastern Europe in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were hardly the modern Mercurians that Slezkine portrays them as being. Slezkine does note that well into the twentieth century the vast majority of Eastern European Jews could not speak the languages of the non-Jews living around them, and he does a good job of showing their intense ingroup feeling and their attitudes that non-Jews were less than human. But he ignores their medieval outlook on life, their obsession with the Kabbala (the writings of Jewish mystics), their superstition and anti-rationalism, and their belief in “magical remedies, amulets, exorcisms, demonic possession (dybbuks), ghosts, devils, and teasing, mischievous genies.” These supposedly modern Mercurians had an attitude of absolute faith in the person of the tsadik, their rebbe, who was a charismatic figure seen by his followers literally as the personification of God in the world. (Attraction to charismatic leaders is a fundamental feature of Jewish social organization—apparent as much among religious fundamentalists as among Jewish political radicals or elite Jewish intellectuals.)

After the Revolution, the shtetls disgorged huge numbers of Jews who then became an elite in the USSR, with disastrous consequences for the Russian people, including most notably prominent roles in the secret police (hence the subtitle of my review, “Stalin’s Willing Executioners.” I conclude:

Nevertheless, the critical issue for collective guilt is whether the Jewish enthusiasm for the Soviet state and the enthusiastic participation of Jews in the violence against what Slezkine terms “rural backwardness and religion” (p. 346) had something to do with their Jewish identity. This is a more difficult claim to establish, but the outlines of the argument are quite clear. Even granting the possibility that the revolutionary vanguard composed of Jews like Trotsky that spearheaded the Bolshevik Revolution was far more influenced by a universalist utopian vision than by their upbringing in traditional Judaism, it does not follow that this was the case for the millions of Jews who left the shtetl towns of the Pale of Settlement to migrate to Moscow and the urban centers of the new state. The migration of the Jews to the urban centers of the USSR is a critical aspect of Slezkine’s presentation, but it strains credulity to suppose that these migrants threw off, completely and immediately, all remnants of the Eastern European shtetl culture which, Slezkine acknowledges, had a deep sense of estrangement from non-Jewish culture, and in particular a fear and hatred of peasants resulting from the traditional economic relations between Jews and peasants and exacerbated by the long and recent history of anti-Jewish pogroms carried out by peasants. Traditional Jewish shtetl culture also had a very negative attitude toward Christianity, not only as the central cultural icon of the outgroup but as associated in their minds with a long history of anti-Jewish persecution. The same situation doubtless occurred in Poland, where the efforts of even the most “de-ethnicized” Jewish Communists to recruit Poles were inhibited by traditional Jewish attitudes of superiority toward and estrangement from traditional Polish culture.

In other words, the war against “rural backwardness and religion” was exactly the sort of war that a traditional Jew would have supported wholeheartedly, because it was a war against everything they hated and thought of as oppressing them. Of course traditional shtetl Jews also hated the tsar and his government due to restrictions on Jews and because they did not think that the government did enough to rein in anti-Jewish violence. There can be little doubt that Lenin’s contempt for “the thick-skulled, boorish, inert, and bearishly savage Russian or Ukrainian peasant” was shared by the vast majority of shtetl Jews prior to the Revolution and after it. Those Jews who defiled the holy places of traditional Russian culture and published anti-Christian periodicals doubtless reveled in their tasks for entirely Jewish reasons, and, as Gorky worried, their activities not unreasonably stoked the anti-Semitism of the period. Given the anti-Christian attitudes of traditional shtetl Jews, it is very difficult to believe that the Jews engaged in campaigns against Christianity did not have a sense of revenge against the old culture that they held in such contempt. …

The situation prompts reflection on what might have happened in the United States had American Communists and their sympathizers assumed power. The “red diaper babies” came from Jewish families which “around the breakfast table, day after day, in Scarsdale, Newton, Great Neck, and Beverly Hills have discussed what an awful, corrupt, immoral, undemocratic, racist society the United States is.” Indeed, hatred toward the peoples and cultures of non-Jews and the image of enslaved ancestors as victims of anti-Semitism have been the Jewish norm throughout history—much commented on, from Tacitus to the present.

It is easy to imagine which sectors of American society would have been deemed overly backward and religious and therefore worthy of mass murder by the American counterparts of the Jewish elite in the Soviet Union—the ones who journeyed to Ellis Island instead of Moscow. The descendants of these overly backward and religious people now loom large among the “red state” voters who have been so important in recent national elections. …

There is a certain enormity in all this. The twentieth century was indeed the Jewish century because Jews and Jewish organizations were intimately and decisively involved in its most important events. Slezkine’s greatest accomplishment is to set the historical record straight on the importance of Jews in the Bolshevik Revolution and its aftermath, but he doesn’t focus on the huge repercussions of the Revolution, repercussions that continue to shape the world of the twenty-first century. In fact, for long after the Revolution, conservatives throughout Europe and the United States believed that Jews were responsible for Communism and for the Bolshevik Revolution. The Jewish role in leftist political movements was a common source of anti-Jewish attitudes among a great many intellectuals and political figures. In Germany, the identification of Jews and Bolshevism was widespread in the middle classes and was a critical part of the National Socialist view of the world. As historian Ernst Nolte has noted, for middle-class Germans, “the experience of the Bolshevik revolution in Germany was so immediate, so close to home, and so disquieting, and statistics seemed to prove the overwhelming participation of Jewish ringleaders so irrefutably,” that even many liberals believed in Jewish responsibility. Jewish involvement in the horrors of Communism was also an important sentiment in Hitler’s desire to destroy the USSR and in the anti-Jewish actions of the German National Socialist government. Jews and Jewish organizations were also important forces in inducing the Western democracies to side with Stalin rather than Hitler in World War II.

Another very important, perhaps critical, reason for the persistence of leftist radicalism among the Eastern European Jewish immigrants was that their cousins had done so well in the USSR. In short, Bolshevism was good for the Jews. It wasn’t until the Trotskyists/proto-neocons became aware of anti-Jewish purges from their elite positions after World War II that there was a significant Jewish movement in opposition to the USSR. On the other hand, the many Jewish apologists for Stalinism were the focus of anti-communist campaigns (e.g., Joe McCarthy).

The Jewish involvement in Bolshevism has therefore had an enormous effect on recent European and American history. It is certainly true that Jews would have attained elite status in the United States with or without their prominence in the Soviet Union. However, without the Soviet Union as a shining beacon of a land freed of official anti-Semitism where Jews had attained elite status in a stunningly short period, the history of the United States would have been very different. The persistence of Jewish radicalism influenced the general political sensibility of the Jewish community and had a destabilizing effect on American society, ranging from the paranoia of the McCarthy era, to the triumph of the 1960s countercultural revolution, to the conflicts over immigration and multiculturalism that are so much a part of the contemporary political landscape.

It’s worth noting, however, that the contrast between conservative, assimilating German Jews and their radical cousins can be taken too far. I have already noted how the older established German-Jewish community, led by the American Jewish Committee, often attempted to minimize public perception of their more radical brethren, so they were by no means entirely at odds with their Eastern European cousins. The American Jewish Committee was a fiefdom of German Jewish establishment, composed of wealthy pillars of the Jewish community. Moreover, the activism of the AJCommittee went beyond shielding their radical co-ethnics. They had a long record opposing restrictions on immigration prior to the rise of the Eastern European immigrants and, despite their misgivings about their behavior, made a special effort to facilitate the immigration of Eastern European Jews. Indeed, on the critical issue of immigration, I can’t see any important differences between the older German-Jewish establishment and the newcomers. From Chapter 7 of The Culture of Critique:

The opposition of Jewish organizations to any restrictions on immigration based on race or ethnicity can be traced back to the nineteenth century. Thus in 1882 the Jewish press was unanimous in its condemnation of the Chinese Exclusion Act (Neuringer 1971, 23) even though this act had no direct bearing on Jewish immigration. In the early twentieth century the AJCommittee at times actively fought against any bill that restricted immigration to white persons or non-Asians, and only refrained from active opposition if it judged that AJCommittee support would threaten the immigration of Jews (Cohen 1972, 47; Goldstein 1990, 250). In 1920 the Central Conference of American Rabbis passed a resolution urging that “the Nation . . . keep the gates of our beloved Republic open . . . to the oppressed and distressed of all mankind in conformity with its historic role as a haven of refuge for all men and women who pledge allegiance to its laws” (in The American Hebrew, Oct. 1, 1920, 594).

The American Hebrew (Feb. 17, 1922, 373), a publication founded in 1867, to represent the German-Jewish establishment of the period, reiterated its long-standing policy that it “has always stood for the admission of worthy immigrants of all classes, irrespective of nationality.” And in his testimony at the 1924 hearings before the House Committee on Immigration and Naturalization, the AJCommittee’s Louis Marshall stated that the bill echoed the sentiments of the Ku Klux Klan; he characterized it as inspired by the racialist theories of Houston Stewart Chamberlain. At a time when the population of the United States was over 100 million, Marshall stated, “[W]e have room in this country for ten times the population we have”; he advocated admission of all of the peoples of the world without quota limit, excluding only those who “were mentally, morally and physically unfit, who are enemies of organized government, and who are apt to become public charges.”

Louis Marshall epitomized the pro-immigration activism of the German-Jewish establishment of the period — activism that went far beyond aiding their Eastern European brethren. And even though the Eastern European Jews came to dominate Jewish organizational life by the 1950s, there were echoes of these conflicts during the 1960s. From Chapter 3 of The Culture of Critique:

Jews also tended to be the most publicized leaders of campus protests (Sachar 1992, 804). Abbie Hoffman, Jerry Rubin, and Rennie Davis achieved national fame as members of the “Chicago Seven” group convicted of crossing state lines with intent to incite a riot at the 1968 Democratic National Convention. Cuddihy (1974, 193ff) notes the overtly ethnic subplot of the trial, particularly the infighting between defendant Abbie Hoffman and Judge Julius Hoffman, the former representing the children of the Eastern European immigrant generation that tended toward political radicalism, and the latter representing the older, more assimilated German-Jewish establishment. During the trial Abbie Hoffman ridiculed Judge Hoffman in Yiddish as “Shande fur de Goyim” (disgrace for the gentiles)—translated by Abbie Hoffman as “Front man for the WASP power elite.” Clearly Hoffman and Rubin (who spent time on a Kibbutz in Israel) had strong Jewish identifications and antipathy to the white Protestant establishment.

In short, I agree with Paul Gottfried. The distinction between the Jews deriving from Eastern Europe and the previously existing Jewish community are often important. As noted above, in the absence of the very large number of Eastern European Jewish immigrants, the transformative effects of Jewish activism on the US would not have occurred. The German-Jewish elite did indeed have influence far beyond their numbers, but their tiny numbers and relatively conservative attitudes would have prevented them from having the transformative effects that their much more numerous—and much more radical—Eastern European cousins had.

Comments are closed.